|

An 84-year-old Black female presented to our ophthalmic emergency department for new floaters and decreased vision in her left eye starting the day prior. She denied any flashes of light, pain or recent head or eye trauma.

Her vision was 20/30 OD and 20/200 OS. Her intraocular pressures were measured at 13mm Hg OD and 14mm Hg OS. Examination revealed pupils that were equal in size, with no afferent pupillary defects, and normal extraocular motilities. She was pseudophakic with centered intraocular lenses in both eyes, and her anterior chambers were quiet. The posterior segment of the right eye was normal and revealed only moderate optic nerve cupping consistent with her history of primary open-angle glaucoma. The left eye’s fundus exam was significant for vitreous hemorrhage that was most dense centrally and an interesting retinal lesion located in the nasal periphery that appeared elevated. It was associated with both preretinal and subretinal hemorrhage and had exudates nearby.

The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, diabetes without retinopathy, hypercholesterolemia, peripheral neuropathy and obstructive sleep apnea. She also had a history of breast cancer, diagnosed and treated seven years prior.

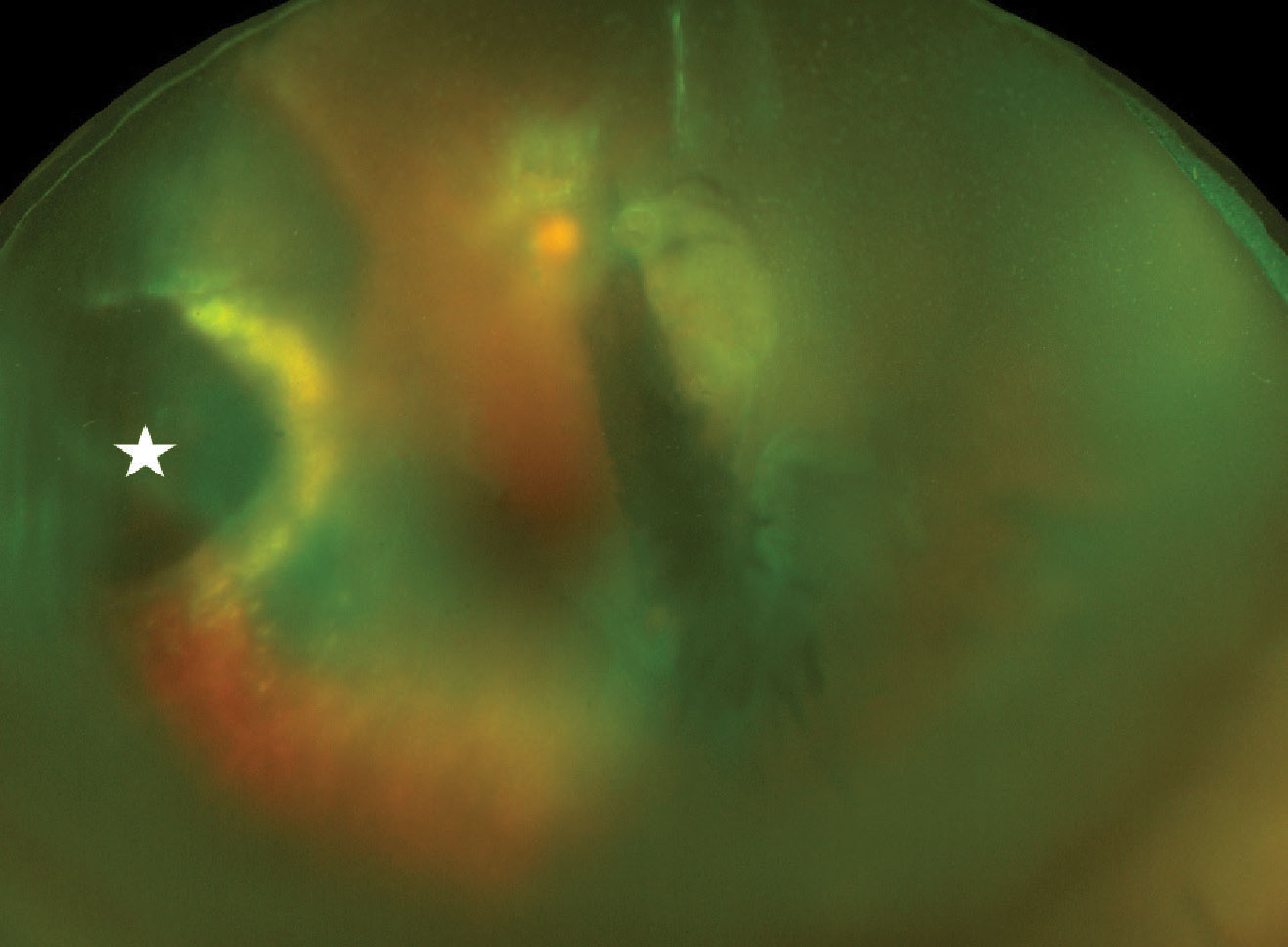

|

| Widefield fundus photo of the left eye on presentation. There is dispersed vitreous hemorrhage blocking the view partially, but a multilayered hemorrhagic lesion (white star) on the left side of the image can be visualized. There is surrounding exudation seen as a yellowish glow. Click image to enlarge. |

Working the Case

Given her history of diabetes, a vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy was considered first. However, the fellow eye did not have even mild diabetic retinopathy, making this unlikely.

The hemorrhagic mass in the periphery raised other suspicions, such as a neoplastic choroidal lesion. Choroidal melanoma may present with choroidal and vitreous hemorrhage, making it a differential in this case.1,2 The patient’s history of breast cancer also made a metastatic lesion a definite possibility.

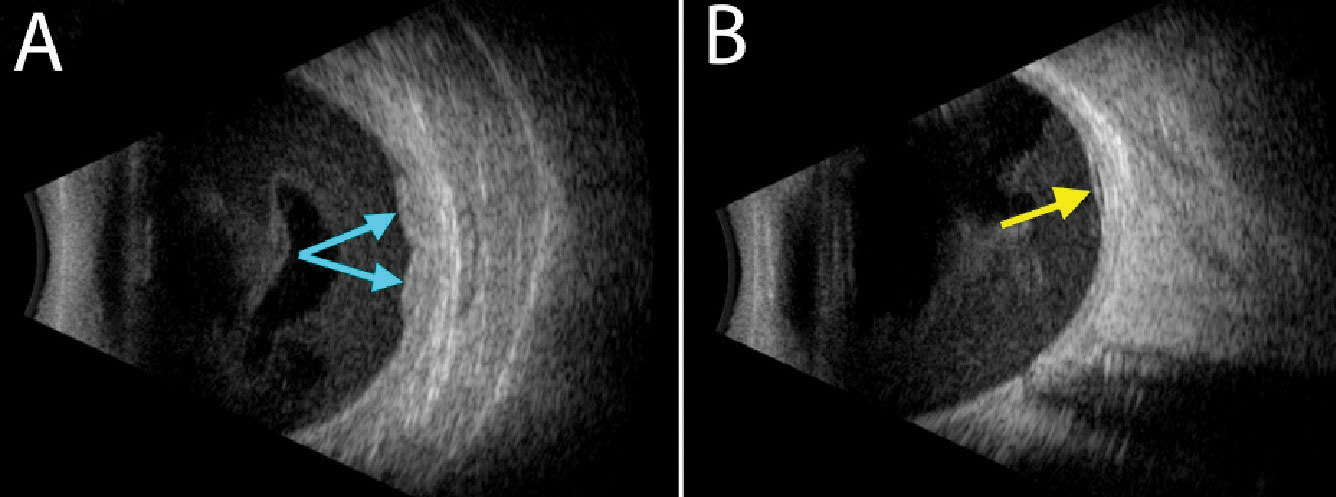

Ultrasonography showed significant vitreous opacities, which corresponded to dispersed vitreous hemorrhage. Additionally, the lesion of concern was hyperechoic and irregularly shaped. There was no internal vascularity appreciable. There was an associated shallow retinal detachment inferior to the lesion, just posterior to the equator. The macula was attached. Due to the irregular, bumpy contour of the lesion and its high internal reflectivity, combined with the clinical examination, a tentative diagnosis of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) was made.

Given the history of breast cancer and the possibility of a metastatic tumor, the patient was referred to an ocular oncologist for further evaluation. The evaluating retina specialist confirmed the likely diagnosis of PEHCR and recommended a trial of anti-VEGF injections. Intravitreal Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech) was used, and during the patient’s one-month return visit, she noted significant improvement in vision, from 20/200 to 20/60. Three additional anti-VEGF injections were administered over the following four months. The lesion shrunk considerably, leaving behind fibrosis and mild exudation. The retina reattached as fluid resolved, and the visual acuity at last follow-up was 20/50, her baseline acuity prior to the hemorrhage.

She continues to be managed by her OD for glaucoma and sees the ocular oncologist/retinal specialist every four to six months to monitor for stability.

|

| Ultrasonography shows a hyperechoic, lobular and solid-appearing area of subretinal thickening (A, blue arrows) with an adjacent small pocket of subretinal fluid (B, yellow arrow). Diffuse hemorrhage can be seen in the vitreous cavity in both images. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

A PubMed search for PEHCR reveals the first article with this condition’s name was published in 1980, but the author references other journal entries describing similar entities from as early as 1961.3 There was then a general paucity of articles discussing PEHCR until the early 2000s, when it began to gain more attention. In 2003, a study determined that PEHCR was the second most common diagnosis for lesions referred to as suspected melanomas, popularizing the term “pseudomelanoma” for PEHCR.4

The condition is described as a peripheral retinal disorder leading to pigment epithelial detachment with subretinal and/or sub-RPE hemorrhage and exudation. At times, the degenerative changes are asymptomatic due to their peripheral location. Other times, sight-threatening complications can occur and include breakthrough vitreous hemorrhaging and exudative retinal detachments. Studies show that the average age at presentation is approximately 77 to 82, and PEHCR is more common in females.5,6 Furthermore, PEHCR has been associated with systemic hypertension and anticoagulant use.7

Hemorrhagic lesions are typically located in the temporal periphery, and they may be dome-shaped, plateau-shaped or multilobular, as was the case with our patient. Ultrasonography is often completed for further characterization of these lesions, which will reveal primarily solid lesions or acoustically hollow lesions, depending on whether the pigment epithelial detachments are filled with hemorrhage or serous fluid.

Intrinsic vascular pulsations are lacking in PEHCR, as this finding would suggest a neoplastic lesion. Fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography can also help evaluate for the presence of pathologic choroidal neovascular networks.5,8

The most commonly employed treatment strategies for patients with PEHCR include monitoring without intervention as most lesions regress on their own, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, photodynamic therapy, laser photocoagulation or a combination of therapies.6,8 There exists no randomized, prospective trial for therapeutic options, but treating patients with high-risk characteristics (e.g., vitreous hemorrhage and exudative macular involvement) more aggressively is highly recommended.6

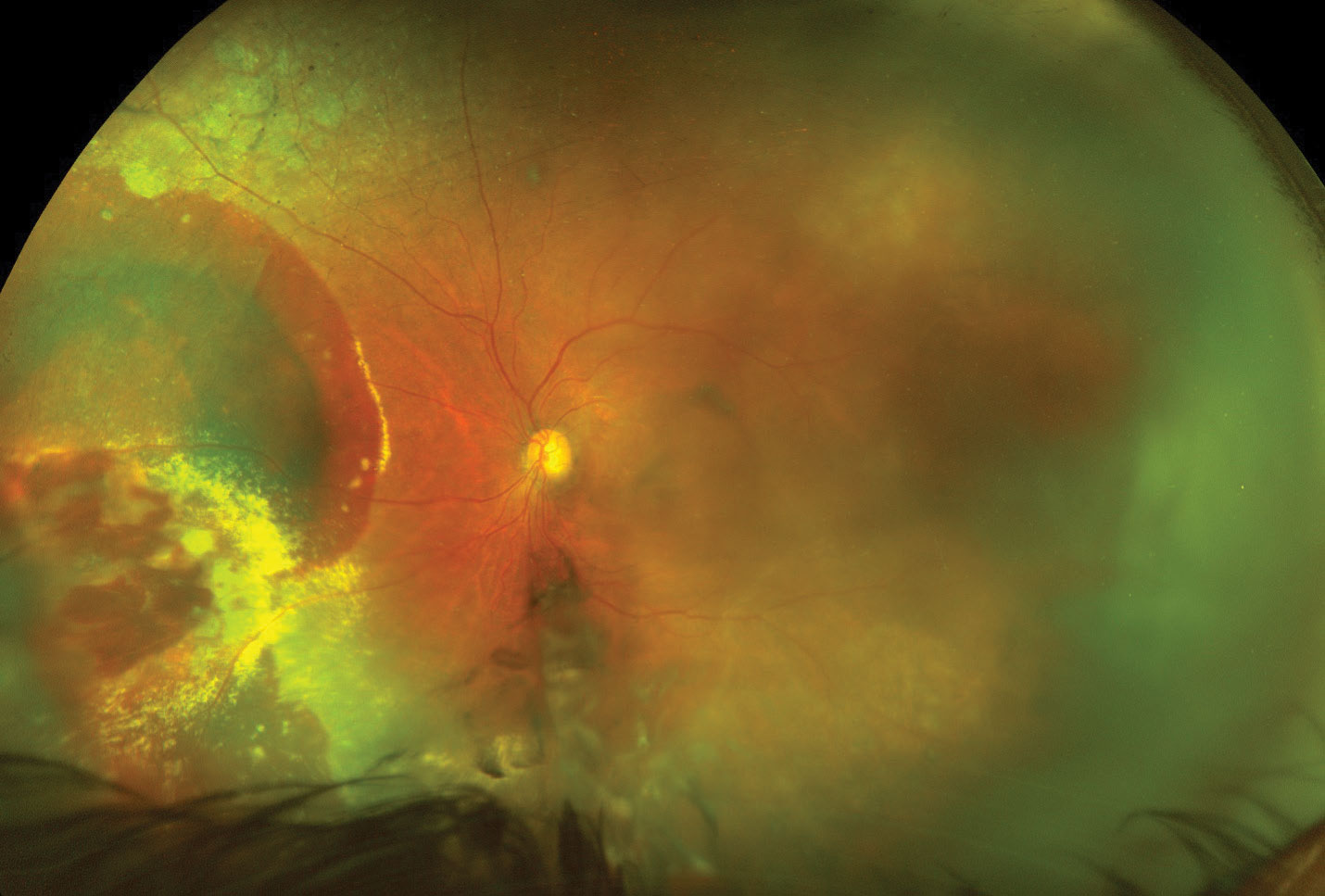

|

| The left eye at the one-month follow-up after a single anti-VEGF intravitreal injection. The vitreous hemorrhage has cleared partially, allowing for better visualization of the nasal retina. You can still make out the extensive hemorrhaging and exudation from the lesion. The vision at this visit improved to 20/60. Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

This case presented an interesting diagnostic challenge, given the patient’s medical history. As optometrists, we should be aware of this disease manifestation and consider it as a differential in cases of hemorrhagic chorioretinal lesions, as it can mimic metastatic or malignant tumors.

Dr. Bozung works in the Ophthalmic Emergency Department of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (BPEI) in Miami and serves as the clinical site director of the Optometric Student Externship Program as well as the associate director of the Optometric Residency Program at BPEI. She has no financial interests to disclose.

|

1. Chee YE, Mudumbai R, Saraf SS, et al. Hemorrhagic choroidal detachment as the presenting sign of uveal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2021;23:101173. 2. Fraser DJ Jr., Font RL. Ocular inflammation and hemorrhage as initial manifestations of uveal malignant melanoma. Incidence and prognosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(7):1311-4. 3. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-64. 4. Shields JA, Mashayekhi A, Ra S, Shields CL. Pseudomelanomas of the posterior uveal tract: the 2006 Taylor R. Smith Lecture. Retina. 2005;25(6):767-71. 5. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical, angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-8. 6. Zicarelli F, Preziosa C, Staurenghi G, Pellegrini M. Peripheral exudative haemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a widefield imaging study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(10):1410-4. 7. Kim YT, Kang SE, Lee JH, Chung SE. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy in Korean patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54(3):227-31. 8. Shields CL, Salazar PF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy simulating choroidal melanoma in 173 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):529-35. |