|

Even though vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) is a common retinal condition, with a prevalence of 14.7% in a 2016 retrospective review, it is often only diagnosed coincidently through the use of OCT.1 When the adhesions alter retinal shape—in particular, the foveal contour—the patient is said to have vitreomacular traction (VMT). The condition has been associated with myriad other maculopathies, including but not limited to macular edema, epiretinal membrane and macular hole formation.

The natural history of the disease is unpredictable, adding to challenges in management. Some cases may remain both stable and asymptomatic for years, while others will show spontaneous resolution if the vitreoretinal interface ultimately achieves a complete posterior vitreous detachment. Yet some cases will progress, which may result in macular hole formation. Although VMT may be asymptomatic, patients may also present with metamorphopsia, relative scotoma and decreased vision.

Given the diversity of presentations, risk profiles and outcomes, optometrists often struggle to decide whether to refer the case to a retina specialist or simply monitor. Seeking consultation relies on numerous variables: Do you have the proper diagnostic modalities, such as OCT? What structural changes are associated with the condition? Is the patient symptomatic? What is your comfort level?

Adding another layer of complexity, treatment approaches also vary. These gray areas form the basis of this new bimonthly column. Each installment will describe a clinical dilemma common in retina care and will share the protocols and rationale of two optometrists who work in retina clinics. Dr. Shechtman practices in Miami and Dr. Haynie in Washington state. Readers will get the benefit of their two perspectives, with one author taking the lead and the other commenting on similarities and differences at the other practice.

|

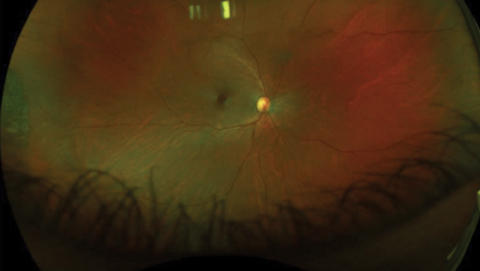

| Fig. 1. The patient presented with 20/50 vision but no complaints. Fundus exam was suspicious for macular hole. Click image to enlarge. |

Hole on the Horizon?

Case by Dr. Shechtman

A 54-year-old Asian female was referred by another optometrist following a fundus exam suspicious for possible macular hole OD (Figure 1). OCT revealed VMT with partial hole. Although her best-corrected visual acuity was only 20/50, she had no visual complaints. Due to the absence of a full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) and symptoms, close observation was recommended. When the patient returned two weeks later, clinical exam showed no changes.

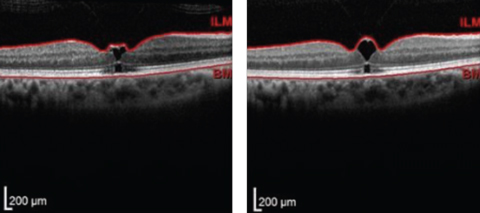

She was then asked to return in one month (Figure 2). At that visit, the patient was advised that if she experienced any visual changes, she should return to clinic immediately. She was also educated on the possibility of pars plana vitrectomy and pneumatic vitreolysis as future treatment options. Close frequent monitoring remains ongoing.

In our practice, functional changes supersede structural ones in the decision-making process regarding whether and when to initiate treatment. The decision to treat typically depends on patients’ symptomology: Is the patient complaining of decreased vision or metamorphopsia even in the presence of minimally affected vision? Does the patient have worsening symptoms, especially if the presentation initially was asymptomatic? Is the patient’s corrected distance visual acuity in the range of 20/40 to 20/70? The answers to these queries also help us recognize a patient who requires consultation.

However, structural changes are not to be dismissed when deciding which patients need a consultation. For example, recalcitrant macular edema or an impeding macular hole (as in this case) should be referred for consultation, as well as progression of the condition or worsening traction, especially in the setting of new symptoms. Additionally, the status of the contralateral eye is significant. Surgeons have a lower threshold to treat VMT in the setting of a full-thickness macular hole of the contralateral eye.

Though some retina surgeons may have considered treatment in this case, our surgeon decided on frequent observation in the absence of patient complaints and in light of the relative small size of the defect. As some VMT cases may detach on their own, the risks and benefits of surgery need to be taken into account.

When considering a referral, keep these factors in mind: (1) the scope of practice laws in your state and the informal ‘community standards’ for optometric care in your area, (2) the diagnostic modalities available to you, (3) your background knowledge on the condition and ‘gut check’ on whether or not this case will keep you up at night, and (4) where the case currently is in the likely timeline of its natural progression, with more advanced status obviously arguing for prompt referral. VMT is not an emergency; referral should be considered within a few weeks.

|

| Fig. 2. Upon referral, the initial OCT scan (left) showed VMT and early macular hole formation, but vision was stable. Follow-up one month later (right) showed slight worsening. Patient was educated of recommendation for vitrectomy if FTMH develops. Click images to enlarge. |

How Our Practice Compares

By Dr. Haynie

My group here in the Pacific Northwest is for the most part quite conservative regarding VMT, given that a large percentage of patients will in fact spontaneously recover with a PVD over time. Still, chronic VMT can alter the photoreceptor layer and reduce the odds of symptomatic improvement even with treatment, so observation is not without risks itself. We consider intervention for those who have been symptomatic for a few months with persistent VMT as seen with OCT. Options include pharmacologic vitreolysis, pneumatic vitreolysis or vitrectomy surgery.

Pharmacologic vitreolysis is an in-office procedure done under local anesthesia using an injection of Jetrea (ocriplasmin, Thrombogenics) to induce posterior vitreous separation, with a reported success rate of 26.5%.2 My group has treated a fair number of patients and achieved an estimated 50% to 60% success rate; however, we have recently reduced its use due to a reported concern of potential photoreceptor toxicity.

Pneumatic vitreolysis, also performed in-office with local anesthesia, induces a posterior vitreous detachment through intraocular injection of gas (either SF6 or C3F8). Though reported success rates vary, it can be as high as 84%.6 Pneumatic vitreolysis is cost effective and convenient, and may likely gain popularity as a result. My group has yet to embrace this modality, however.

Vitrectomy is of course the definitive treatment for VMT, but carries all the higher risks and costs of a surgical procedure. My group will consider vitrectomy for VMT that has been chronic or associated with a stage 2 macular hole on OCT imaging.

In summary, the management of symptomatic VMT demands case-by-case decisions. A detailed discussion with the patient regarding the treatment options is the most important, in my opinion. Knowing that a high percentage of patients will experience release of traction with a PVD over time, initial observation is the most popular management choice in my group currently. We largely concur with the management course outlined by Dr. Shechtman.

1. Reichel E, Jaffe GJ, Sadda SR, et al. Prevalence of vitreomacular adhesion: an optical coherence tomography analysis in the retina clinic setting. Clin Ophthalmol 2016;10:627-633. |

For more information, visit the authors’ practice websites.

Dr. Shechtman: www.retinamaculamiami.com

Dr. Haynie: www.retina-macula.com