|

An 80-year-old Caucasian female presented with new floaters in her left eye, which started about a month ago. She reported her right eye sees well. Her past ocular history was significant for cataract surgery in both eyes more than 10 years ago. Her last eye exam was two years earlier. Her medical history was significant for hypertension and high cholesterol.

On examination, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/400 OS. Confrontation visual fields were full-to-careful finger counting. The anterior segment was remarkable for posterior chamber lens implants in both eyes.

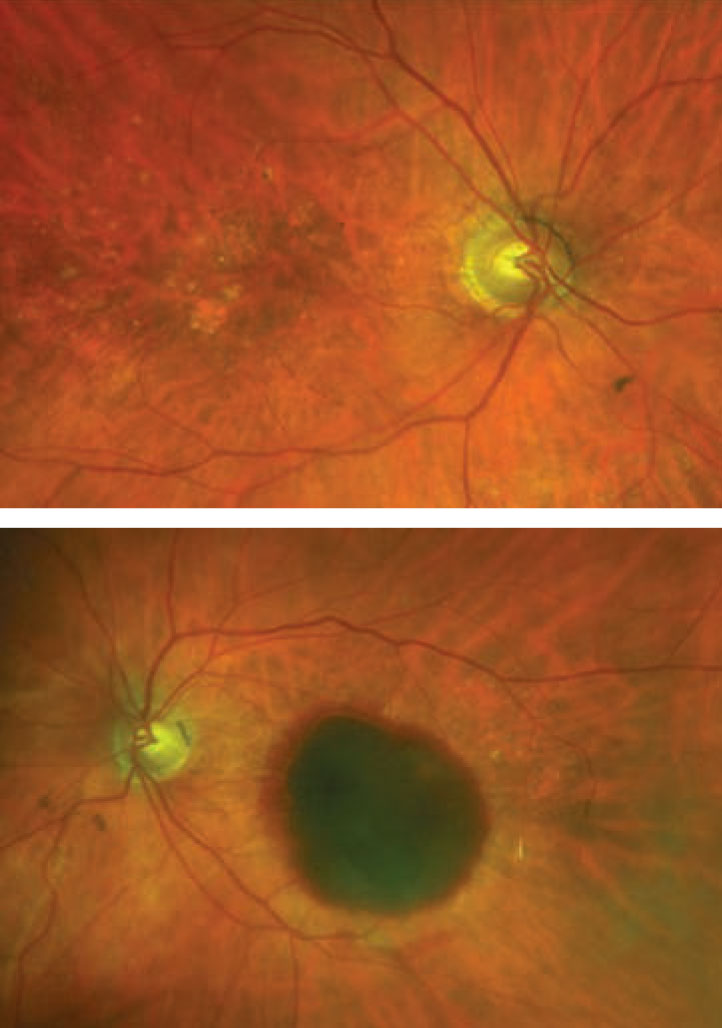

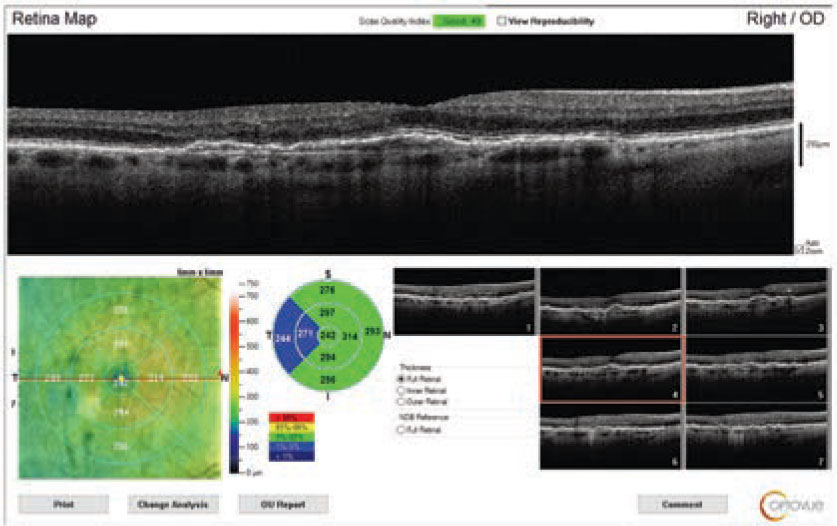

Dilated fundus exam showed clear media. She had moderate-size cups with good rim coloration and perfusion. The macula of both eyes were significant for changes (Figure 1). An SD-OCT is available for review of the right eye (Figure 2).

|

| Fig. 1. In these photos of the right (top) and left (bottom) eyes, where is the blood located? Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. How would you characterize the macula in the left eye?

a. Preretinal hemorrhage

b. Subhyloid hemorrhage

c. Subretinal hemorrhage

d. Sub-RPE hemorrhage

2. What is the cause of the hemorrhage in the left eye?

a. Valsalva maneuver

b. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy

c. Retinal arterial microaneurysm

d. Choroidal neovascularization (CNV)

3. How would you describe the OCT findings in the right eye?

a. Normal

b. Shallow elevation of the RPE and Bruch’s membrane

c. Double-layer sign

d. RPE detachment

4. What is the correct diagnosis for the right eye?

a. Early-stage age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

b. Intermediate-stage dry AMD

c. AMD with geographic atrophy

d. Wet AMD with CNV

5. How should our patient be managed?

a. Close observation

b. Observe the right eye, anti-VEGF injection in the left eye

c. Observe the right eye, surgical vitrectomy for the left eye

d. Anti-VEGF injection in both eyes

For answers, see below.

Discussion

It is obvious from the fundus photos that our patient has macular degeneration. The patient fits the demographic perfectly, and her clinical finds are also consistent with macular degeneration. In the right eye, there are scattered drusen in the macula and posterior pole. There is also a focal area of geographic atrophy that can be seen inferotemporal from the fovea. The clinical question that needs to be determined—is this still dry AMD, or has she converted to the wet form of AMD?

To determine the stage of AMD, try and quantify the extent and size of the drusen. From the Beckman classification of AMD, early-stage AMD is defined as medium-sized drusen measuring between 63µm and less than 125µm with no pigmentary abnormalities. In intermediate-stage AMD, there needs to be at least one large drusen larger than 125µm and/or pigmentary abnormalities.1

The size of the drusen in our patient is at least 125µm, which, for comparison, is the size of the central retinal veins. There are also pigmentary abnormalities

present, making this intermediate-stage AMD at minimum.

The macula looked flat, and there was no exudate or subretinal hemorrhage present, so, based on the clinical exam, she wouldn’t have a CNV. However, the OCT tells a different story. On the OCT, we can see a shallow elevation of the RPE, and, below that, another reflective band that corresponds to Bruch’s membrane. That OCT pattern has been referred to as a “double-layer sign (DLS)” and is very specific for CNV. With the DLS, the CNV resides in the space between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane.2 Unfortunately, based on this finding, our patient has probably converted to wet AMD.

The left eye is very striking, with the massive hemorrhage involving the macula. The blood is below the RPE and has caused a hemorrhagic detachment of the RPE due to a choroidal neovascular membrane. Unfortunately, we were not able to capture a quality OCT image.

Management

The treatment for wet AMD has evolved considerably over the past 15 years. Intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF medication have revolutionized AMD management. These medications include ranibizumab, afilbercept and bevacizumab; all three show great efficacy in treating CNV. Treatment choices are based on physician preferences as well as economic considerations, with bevacizumab being the least expensive.

The majority of clinical trials have shown monthly injections to be slightly more favorable than PRN injections when it comes to visual outcomes. The main advantage of PRN injections is reduced treatment frequency over the first year: approximately six to seven injections for PRN dosing compared with 10 to 11 injections for monthly dosing.3

|

| Fig. 2. What can you see in this SD-OCT of the right eye through the macula? Click image to enlarge. |

Treat and extend (T&E) is also a protocol many retinal specialists use around the world. They treat patients monthly for three months and every visit thereafter. If there is no sign of exudation, the treatment intervals are gradually extended for one to two weeks. When there are signs of recurrence, the intervals are shortened.

The ultimate goal is to maintain an exudation-free macula with minimal number of injections and fewer office visits. This might reduce the cost, but will it translate into comparable visual outcomes?

Injection Scheduling

The TREX study compared monthly injections to T&E dosing and showed fewer injections (25.5 in the monthly group compared with 18.6 in the T&E groups) with similar visual acuity outcomes, though the monthly injection group trended toward better vision.4

Unfortunately, visual outcomes tend to worsen when patients receive less frequent injections. In the SEVEN-UP study, patients, at seven years, on average lost 8.6 letters from baseline.5 Those receiving either fewer than five injections or none lost on average 8.7 letters and 10.8 letters from baseline, respectively. Patients receiving more than 11 injections gained 3.9 letters from baseline.5

More recently, a 10-year study compared T&E vs. PRN dosing outcomes from Australia-New Zealand (ANZ) and Switzerland.6 The investigators showed that the ANZ group’s vision decreased by 0.9 letters from baseline at 10 years with a T&E regimen that resulted in a median of 5.3 injections/year compared with the Swiss patients, whose vision decreased by a mean of 14.9 letters on a PRN regimen with a median of 4.2 injections per year.

The study concluded that continuous treatment and more injections achieved better visual outcomes. Other studies show similar outcomes with the central message being that, on average, more injections translates into better vision.6

Our patient received intravitreal injections in both eyes. In the left eye, she received three monthly injections before discontinuing due to a guarded prognosis. Her vision is stable at 20/200. The right eye had monthly injections of bevacizumab (extended out to six weeks) for a total of 16 injections. Her vision has been stable at 20/30.

1. Ferris FL, Wilkinson CP, Bird A, et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(4):844-51. 2. Motulsky E, Rosenfeld PJ. Double-layer sign and type 1 CNV. Retina Specialist. 2017;6:12-3. 3. CATT Research Group. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(20):1897-1908. 4. Wykoff CC, Ou WC, Brown DM, et al. Randomized trial of treat-and-extend versus monthly dosing for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results of the TREX-AMD study. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(4):314-21. 5. Rofagha S, Bhisitkul RB, Boyer DS. et al. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA and HORIZON: A multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2292-9. 6. Gillies M, Arnold J, Bhandari S, et al. Ten-year outcomes of neovascular age-related macular degeneration from two regions. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;210:116-24. |