A 46-year-old white male presented complaining of bilateral irritation, photophobia and decreased vision during the past eight months. Best-corrected acuity measured 20/50 O.D. and 20/60 O.S. Biomicroscopic evaluation revealed bilateral anterior uveitis with fine keratic precipitates O.U. Both pupils were poorly reactive secondary to posterior synechiae. Intraocular pressure measured 24mm Hg O.U.

Funduscopic examination in both eyes proved difficult due to posterior synechiae, poor dilation and early cataract formation. Inflammatory cells were noted in the anterior vitreous of both eyes as well. The posterior pole of each eye appeared flat and intact through cloudy media.

For each eye, we prescribed a high dose (one drop every 30 minutes during waking hours) of Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate, Allergan) and scopolamine 0.25% t.i.d. Topical phenylephrine 10% was instilled in-office to help break the synechiae. After several weeks of therapy, there was little positive response in the amount of inflammation, IOP or symptoms. Ultimately, we consulted with a uveitis specialist about systemic therapy.

Treating ocular disease is an exciting and rewarding aspect of primary-care optometrythat is, when everything goes according to plan. Unfortunately, even the best-educated and skilled practitioners can encounter patients such as this one who have recalcitrant disorders. What do you do when the tools you have wont do the job? In the case of uveitis, you often must go beyond topical agents. These patients may require oral and/or injectable steroids and immunomodulatory agents. Here is a review of these agents.

|

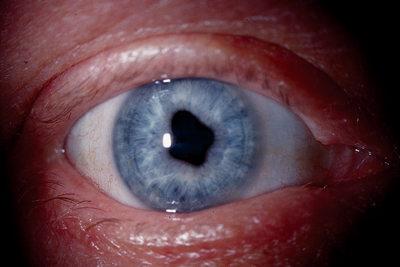

| The patients right eye displayed areas of posterior synechiae, leading to an irregular, clover-leaf pupil. |

|

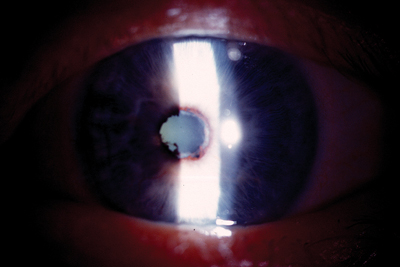

| A closer view of the pupillary margin of the patients left eye shows synechiae and atrophy. The anterior chamber is visibly hazy. |

Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids are often the treatment of choice for non-responsive anterior, intermediate and posterior uveitis. Prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg (or up to 2mg/kg in moderate to severe cases) is recommended as initial therapy, followed by a slow taper as resolution occurs. In most cases, an H2 receptor antagonist, such as Zantac (ranitidine, GlaxoSmithKline) 150mg p.o.b.i.d. is prescribed concurrently to prevent secondary gastrointestinal problems, such as stomach upset and ulcers.

Unfortunately, oral corticosteroids are associated with other well-known potential complications, including cataractogenesis, secondary glaucoma, sodium retention (leading to hypertension and edema), weight gain, headache, hirsutism (abnormal hairiness), impaired wound healing, osteoporosis, and worsening of diabetes. As with topical corticosteroid therapy, complications occur more frequently with higher doses and prolonged treatment.

Periocular corticosteroid injections are another option for recalcitrant anterior uveitis or intermediate uveitis (e.g., pars planitis). A small amount of depot corticosteroid, such as 1.0ml of 40mg/ml triamcinolone acetonide, may be injected into the periorbital region in such situations.1

While steroid injections circumvent many side effects associated with systemic corticosteroids, complications may still arise. IOP response is a particular concern, especially given that medication cannot be removed as easily as an oral or topical preparation, which the patient can taper or discontinue.

A recent development for the management of intermediate and/or posterior uveitis is Retisert (fluocinolone acetonide 0.59mg, Bausch & Lomb), a sustained-release intra-vitreal corticosteroid implant. Reti-sert is indicated for the treatment of chronic, non

infectious uveitis that affects the posterior segment of the eye.2 A new intravitreal dexamethasone implant is also under investigation.3

Unfortunately, patients treated with these devices can also encounter complications. Within an average post-implantation period of approximately two years, nearly all phakic eyes are expected to develop cataracts and require cataract surgery, and approximately 32% of patients are expected to require filtering procedures to control intra-ocular pressure.4

Immunosuppressive Drugs

In cases of severe sight-threatening uveitis, for which steroids are ineffective or poorly tolerated, immunosuppressive agents may be used. Immunosuppressive agents slow or inhibit the bodys natural immune responses, including those directed against the bodys own tissues. These drugs, while tremendously helpful for some individuals, may have varied and potentially severe systemic complications, such as hypertension and renal toxicity. So, they should only be prescribed by clinicians who are well-trained in their use and able to manage their side effects.

A relatively new category of immunosuppressive drugs, including Remicade (infliximab, Centocor), Enbrel (etanercept, Amgen/ Wyeth) and Humira (adalimumab, Abbott), may also hold promise for treating refractory cases of uveitis. These agents selectively inhibit tu-mor necrosis factor (TNF), another key player in the autoimmune-inflammatory cascade.

Several reports suggest that infliximab, in particular, may be beneficial in cases of severe, unresponsive uveitis.5,6 Currently, the Remicade European Study for Chronic Uveitis (RESCU) is evaluating the safety and efficacy of infliximab in patients who have intermediate and posterior uveitis.

Immunomodulatory Drugs

Immunomodulatory drugs are capable of modifying or regulating one or more immune functions. Chemotherapeutic alkylating drugs, such as oral Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide, Bristol-Meyers Squibb) and Leukeran, (chlorambucil, GlaxoSmithKline) are two choices among the vast array of immunomodulatory drugs. These drugs interfere with DNA replication and transcription, resulting in depression of T- and/or B-cell populations.

Antimetabolites, including methotrexate, Imuran (azathioprine, GlaxoWellcome) and CellCept (mycophenolate mofetil, Roche Pharmaceuticals), are other potential options. These agents selectively compete for intermediary metabolites that are critical to immune cell function (e.g., folic acid or purines). This, in turn, induces a cytotoxic effect on immune cells.

Neoral (cyclosporine capsules, Novartis), another common immunomodulatory agent, is classified as an antibiotic drug, but not in the conventional sense. In inflammatory states, Neoral inhibits T-cell proliferation and blocks production of interleukin-2, a powerful pro-inflammatory mediator.

Prograf (tacrolimus, Astellas Pharma US) works by a similar mechanism as cyclosporine, inhibiting T-cell activation and proliferation. Cyclosporine is most commonly prescribed for moderate to severe uveitis, while tacrolimus is typically used for refractory cases or in patients who have known hypersensitivity to cyclosporine.

In cases of sight-threatening ocular disease, recognize that some presentations will simply exceed your capabilities. In these situations, we are obligated to properly diagnose the patient and refer him or her to an appropriate medical specialist. Additionally, we must properly educate the patient about the course of the disease and likely therapeutic interventions. While the use of systemic immunomodulatory agents may fall outside your scope of practice, you need to be familiar with their uses and potential side effects so that you can provide the most-up-to-date information to your patients.

Drs. Kabat and Sowka are members of Alcons speakers alliance and on VSPs approved speakers list. Dr. Kabat is on the Board of Optometric Consultants for Cynacon/ OCuSOFT. Dr. Sowka is a member of Carl Zeiss Meditecs Speakers Bureau and a paid consultant for Carl Zeis. They have no financial interest in any of the products mentioned.

1. Smith JR. Management of uveitis. Clin Exp Med 2004 Sep; 4(1):21-9.

2. Jaffe G, Bennun J, Guo H, et al. Fluocinolone acetonide sustained drug delivery device to treat severe uveitis. Ophthalmology 2000 Nov;107(11):2024-33.

3. Jaffe G, Pearson A, Ashton P. Dexamethasone sustained drug delivery implant for the treatment of severe uveitis. Retina 2000; 20(4):402-3.

4. Bausch & Lomb Incorporated. Retisert package insert, 2005.

5. Joseph A, Raj D, Dua HS, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of refractory posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology 2003; Jul;110(7): 1449-53.

6. Murphy CC, Ayliffe WH, Booth A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade with infliximab for refractory uveitis and scleritis. Ophthalmology 2004 Feb;111(2):352-6.