Many eyelid lesions are so commonplace in clinical practice that the finding is dismissed, but some raise suspicion and a few generate concern for malignancy—particularly lesions that have changed in size, shape or color; are itchy or have ulceration, scabbing or bleeding, or with other concerning clinical features. Differentiating benign from pre-malignant or malignant is crucial to help guide appropriate management and referral.

Here’s a look at many of the frequently observed eyelid and periocular lesions along the benign to malignant spectrum.

|

| Basal cell carcinoma of the lower eyelid margin. Note the ulceration of the superior aspect, the lesion’s pearly elevated margins and madarosis. Click image to enlarge. |

Benign Lesions

The location of many benign and pre-malignant eyelid lesions, such as seborrheic keratosis (SK), actinic keratosis (AK) and Bowen’s disease, is related to chronic and direct sun exposure—making their occurrence most typical on the lower eyelids.1,2 Many of these lesions are only of cosmetic concern, though in some cases they can induce astigmatism or eyelid disfigurement that requires intervention.

Chalazia. These are firm, well-defined nodules in the subcutaneous eyelid tissue, within the tarsal plate. They typically form as chronic sequelae to an acute meibomian gland hordeolum. Chalazia are comprised of consolidated lipogranulomatous tissue.3 They may present with acute inflammation but more often are non-tender and a cosmetic aggravation.4 They tend to be found in patients with concomitant blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).

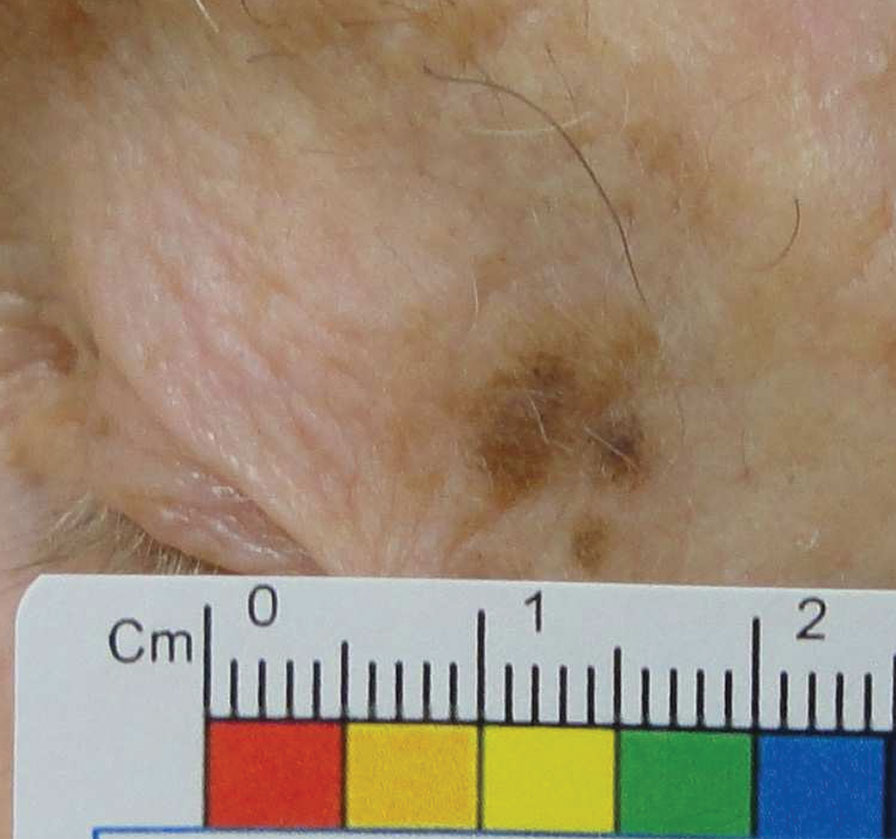

|

| Melanoma in situ of the lateral upper eyelid. Note the lesion’s asymmetry and irregular borders, satellite lesions and variable pigmentation. Click image to enlarge. |

Frequent warm compresses and gentle massage over the lesion may lead to improvement or resolution, though resolution is less likely if the chalazion has been present for two months or more.4 The additional use of antibiotic or antibiotic/steroid solutions or ointments can also be effective, but does not appear to improve resolution outcomes or overall lesion size compared with warm compresses alone.4 If unresolved, intralesional steroid injection or incision and curettage are the next therapeutic steps.

In cases of locally recurrent chalazion, be on high alert for sebaceous cell carcinoma (SCC), particularly in older patients.

Epidermal inclusion cysts. These are common cutaneous lesions, often referred to as epidermoid, epidermal, inclusion or keratin cysts.5 They contain keratinized squamous epithelium and lipids, which may be odorous if ruptured. They are dome-shaped and creamy- or skin-colored and often have a superficial central keratin plug. These cysts may form directly within a hair follicle if its orifice becomes obstructed, or may form secondary to dermal trauma or acne, whereby the epithelium implants into the dermis.5 Epidermal inclusion cysts mostly remain quiescent, but in some cases can grow and become inflamed, infected or rupture.5 Rarely, case reports have described their development into SCC, but its documented occurrence is so rare that monitoring or biopsy are not necessary.6

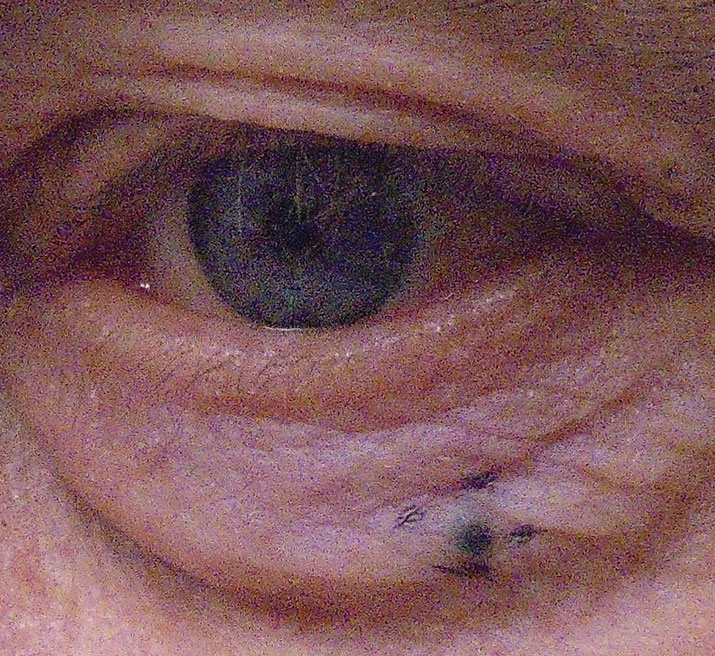

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the cheek. Note the raised margins and scaly surface. Click image to enlarge. |

Table 1. The ABCDEs of Melanoma |

| Signs concerning for malignant transformation of a nevus into melanoma |

| Asymmetry: if any two halves of a lesion are not symmetric |

| Borders: irregular borders or development of satellite pigmentation |

| Color: uneven color or changes in color (especially white, gray, red or blue) |

| Diameter: enlarging size or >6mm diameter |

| Elevation |

| Other concerning changes include ulceration, scaling, discharge or bleeding |

Surgical excision of the cyst with its walls is the definitive treatment, though observation is acceptable in asymptomatic cases.5

Hidrocystoma. Apocrine and eccrine sweat glands are found along the eyelid margins and in the pretarsal and preseptal skin, respectively.7 Hidrocystomas, which develop in these glands, are fluid-filled solitary cystic elevations that are translucent or may have a bluish hue.2

Traditional treatment involves incision and drainage; however, improvement tends only to be temporary, as the cysts often re-fill within two to six weeks.8 Electrodessication of the walls of the cyst and cautery may help delay recurrence, but the cysts can remain untreated if they are not bothersome to the patient.8,9

Seborrheic keratosis. This is the most common benign tumor and is frequently seen on the face, particularly in elderly patients. These epithelial proliferations are typically darkly pigmented, slightly raised and well-defined with a scaly texture of ridges and fissures that often appear as if they are “stuck on” the skin. They do not transform into malignancy but can be removed as needed with cryotherapy, curettage or ablative laser.10

Pre-malignant Lesions

For pre-malignant lesions, the commonly used term in situ refers to a group of abnormal cells confined to the epidermal layer but not breaching the basement membrane. A breach would be considered invasive carcinoma.11 Identifying and properly managing or referring these lesions may be critical to the patient’s long-term outcomes.

|

| This patient had BCC of the lower eyelid. Above is the immediate post-op s/p Mohs micrographic surgery with Tenzel closure. Below is one year post-op. Click image to enlarge. |

Nevi. Melanocytic nevi are quite common and are often referred to as moles.2 Junctional nevi may be present at birth or may develop before early adulthood. These are pigmented, flat macules that grow over time into the common compound (epidermal and dermal) or intradermal nevus.2 Excision or shave is optional if they are troublesome to the patient. Nevi are dynamic and grow over time, but clinicians should monitor them for atypical features that would warrant referral to evaluate for melanoma (Table 1).

Actinic keratosis. Also known as solar keratosis, this is a clinical sign of photo-aging—sun-related skin damage to exposed areas.11,12 These lesions demonstrate intraepithelial keratinocytic dysplasia and are in situ SCC, precursors of invasive SCC.11 AK usually appears as pink, but possibly tan or red, pustules or plaques, which may become scalier with time; hypertrophy or bleeding should increase suspicion for SCC.13 Because the clinical features of AK are fairly nonspecific with broad differentials, clinicians should refer for biopsy when they present in high-risk anatomical locations or in high-risk patients, such as those with a history of skin cancer or immunosuppression.13 Anatomic locations considered higher risk for carcinoma due to chronic sun exposure include the eyelids and periorbital region, the dorsal hands, legs, forearms, ears and lips; most SCC in these regions arise from AK.12 They are not often solitary but more frequently develop as a cluster of lesions; AKs are rarely found on the eyelids and periorbital regions but should raise high suspicion for malignancy when they do.12

Evaluation PearlsBecause 15% to 20% of periocular lesions are malignant, comprehensive eye examinations should include questioning regarding prior skin cancers and the extent of UV exposure.19,20 Clinicians should document objective findings such as skin type, lesion size, changes to pre-existing lesions, ulceration, pigmentation, madaroisis, induration, symptoms such as itching or bleeding and changes to eyelid architecture and function. Cervical, preauricular, parotid and submandibular lymph nodes should be palpated for firmness and tenderness.34 Clinicians should photograph all suspicious lesions and refer patients to dermatology, tele-dermatology or oculoplastics for evaluation. If a full eyelid examination reveals any signs of orbital invasion such as strabismus, hyper- or hypo-globus, extraocular muscle dysfunction and proptosis, clinicians should evaluate these patients with neuroimaging.22 |

Around 25% of AK lesions may spontaneously regress over their inaugural year without intervention, though many later recur locally, and the rate of malignant transformation from AK to invasive SCC is estimated at 0.1% to 10%.12,14

Definitive treatment with excisional biopsy with permanent pathology or frozen sections is frequently used for AK around the eye; in some cases, Mohs micrographic surgery is needed, and several other treatment options exist such as topical chemotherapy or cryotherapy.15

Mohs is a microscopically controlled excisional surgery that involves removing a lesion with a small amount of its surrounding tissue in tangential sections, evaluating the tissue’s margins microscopically for cell content, then progressively enlarging the excised area until all margins contain only normal, cancer-free tissue. The tissue is processed into stained frozen sections for microscopic evaluation of each plane’s content to decipher whether further micro-excision is needed. The goal of this surgery is to fully remove the lesion of concern, ensuring clear margins to reduce the rate of local recurrence but minimizing healthy tissue loss. Following excision, primary wound closure, second-intention healing or reconstruction ensues.16

|

| Seborrheic keratosis of the nasal sidewall is less scaly and ridged than often seen, and could be mistaken for melanoma. Click image to enlarge. |

Keratoacanthoma. This unusual lesion grows rapidly over weeks in a dome shape, remains stable for a few weeks, then involutes to include a keratin-filled center, creating its characteristic crater-like appearance. The lesion is fleshy with telangiectatic surface vessels and possibly erythema at its margins. It is also a squamoproliferative process, which can ultimately result in invasive SCC. Keratoacanthoma is atypical in the periorbital area, despite it being most commonly found in other highly sun-exposed regions; it is found more typically in males in their 40s to 60s.17

Keratoacanthoma can fully regress without any intervention.18 However, while keratoacanthoma’s clinical appearance seems unique, it is not clinically pathognomonic, and histology is necessary to definitively rule out invasive SCC.17 Full excision with margin control, recommended for all periorbital lesions suspected to be keratoacanthoma, provides a low recurrence rate.17 Even if not found to be SCC, excision will prevent local tissue destruction.

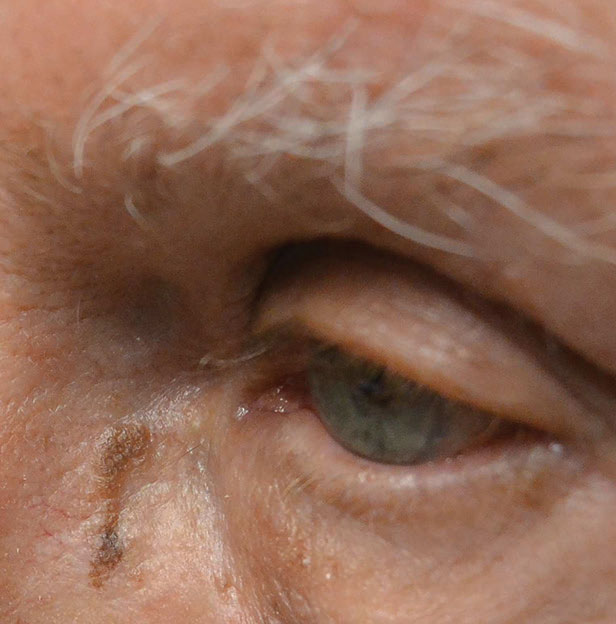

|

| Nodular melanoma of the lower eyelid. Click image to enlarge. |

Malignant Lesions

Eyelid malignancies carry a considerable risk of globe and vision impairment, given that eyelid and periocular tissue destruction can impair the tear drainage apparatus, eyelid position, muscular function and local glandular secretions. This is true for both the lesion itself and after its excision and repair. Ultraviolet (UV) exposure is the principal risk factor for all of the following eyelid malignancies.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC). This accounts for 90% to 95% of eyelid malignancies, making them the most frequently encountered.19 Eighty percent of BCCs occur on the head and neck, with 20% of these being periocular.20 BCCs within the periocular area are most commonly located on the lower eyelid (50% to 60%), followed by the medial canthus (25% to 30%).19 They can also be found on the upper lids and lateral canthus.21 Risk factors for BCC include advancing age, UV exposure (particularly during adolescent years), immune suppression, fair skin with red or blonde hair and blue eyes and smoking.20-22 BCC has no sex predilection.23 BCC rarely metastasizes but can be locally invasive.

Table 2. AEIOU Findings Consistent with Merkel Cell Carcinoma35 |

| Asymptomatic |

| Expands rapidly |

| Immune suppression |

| Older than 50 years |

| UV exposure to fair skin |

BCC is subdivided into types, each with its own distinguishing features. The nodular subtype is the most common, representing anywhere between 43% and 77% of presentations.20 These tend to present as painless nodular lesions, but may cause symptoms of itching or bleeding.20 These lesions can be white with pearly raised edges, telangiectatic vessels and central ulcerations, which are expected with increasing size.20,24 Growth is slow and insidious and can cause madarosis if at the lash line.20

Rodent ulcers, a variant of the nodular subtype, are described as solid, circumscribed and often scab.21

The morpheaform subtype of BCC is more aggressive and presents as solitary, pale, flesh- or yellow-colored with poorly defined margins.20 These lesions can be located in the medial canthus. Because of the morpheaform nature, a greater likelihood for incomplete resection and recurrence exists and therefore recurrence.21

For all variants of BCC, complete excision with Mohs is expected 99% of the time with recurrence rates of up to 3% overall; the five-year local recurrence rate after Mohs for primary BCC is 1% and 5.6% for recurrent BCC.19,25-27 Comparatively, standard excisions (non-Mohs) are incomplete for up to a quarter of periocular BCC with recurrence rates as high as 30% to 50%.20,25 Because up to 18% recur at five years, long-term monitoring post-excision is advised.25

Squamous cell carcinoma. This is the second most common eyelid malignancy comprising 3.4% to 12.6%.20 SCCs occur two to three times more frequently in men than women with a median age of onset in the sixth and seventh decades.22 As with BCC, SCC are commonly found on the lower lids and medial canthi.21 Risk factors include UV exposure, fair complexions, immune suppression, high fat diets, chemical exposures, smoking and human papilloma virus (HPV).20

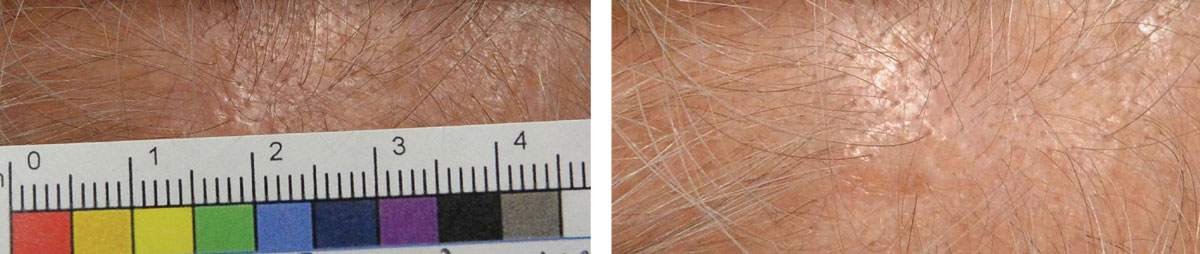

|

| Typical appearance of SK, seen here on the scalp. Click image to enlarge. |

SCC can arise de novo or from AK, Bowen’s disease, keratoacanthoma or post-radiation treatment exposure.19 Bowen’s disease is SCC in situ, which histologically shows full thickness epidermal squamous cell dysplasia.28 It is a superficial skin cancer in an early stage but may progress to invasive SCC in 3% to 5% of cases.29

SCC presents similarly to BCC. Their natural course generally begins as a painless, small raised keratin patch, which slowly transforms to a papillomatous lesion and then to a larger ulcerated lesion.22 These are commonly misdiagnosed as chronic anterior blepharitis.20

SCCs tend to be invasive and patients are at risk for metastasis through direct extension of cancerous cells into surrounding tissue or through the lymphatic system.19 Overall, SCC comprises greater than 20% of non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) and account for the most metastatic disease and mortality from NMSC.13 The risk for tissue destruction is significant.

Reported recurrence rates are similar to that of BCC at 2.4% to 36.9% at five years, with the extremes of the range relating to Mohs versus standard excision.20 The five-year recurrence after Mohs for recurrent SSC is 10%. For primary SCC that is well differentiated without metastasis, the recurrence rate after Mohs is 2% to 3%.30

|

| This patient with actinic keratosis of the scalp has a subtle lesion that is pinkish-tan and slightly elevated. Click image to enlarge. |

Sebaceous cell carcinoma. This accounts for only 5% of eyelid neoplasms, although the incidence is higher for Asians than Caucasians.24 These lesions arise from meibomian and zeiss glands and are more likely to occur on the upper eyelid due to the preponderance of glandular ducts in this region.21 Female patients and those in their late 50s to early 70s are at increased risk.20 Sebaceous cell carcinomas present as painless solitary nodules or a diffuse thickening with erythema.21 Madarosis will often occur if the lesion’s source is a zeiss gland. The lesions can be yellow due to the lipid content within the neoplastic cells.19 Although a rare presentation, sebaceous cell lesions can ulcerate and mimic BCC.24

Differentials include recurrent chalazion, blepharoconjunctivitis, BCC or SCC. These lesions are misdiagnosed, clinically and pathologically, up to two-thirds of the time, which can delay appropriate treatment by as much as one to two years.20,22

Hallmark features of this malignancy are pagetoid spread (26% to 47% of the time) and aggressive local extension.22 Pagetoid spread is defined as intraepithelial growth that often extends over the conjunctiva.19 Conjunctival involvement presents as injection with or without papillary reaction.20 Therefore, clinicians should suspect sebaceous cell carcinoma in cases of un-resolving unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis. Recurrence rates differ based upon the presence of pagetoid spread—36% with vs. 7% without—implying that epithelial involvement greatly affects prognosis.19 Lymph involvement ensues through perineural infiltration and invasion. Metastasis to lymph nodes and distal organs occurs in 8% to 18% and 3% to 8% of cases, respectively.22

Treatment PearlsIncisional or excisional biopsies are indicated for most eyelid malignancies, with excisional reserved for the more aggressive forms. Considerations for skip lesions and pagetoid spread associated with sebaceous cell carcinoma may require full thickness or map biopsies.20 Varying risks of metastasis to lymph nodes with all eyelid malignancies (except BCC) warrant sentinel lymph node biopsies, although some surgeons dispute this, citing little to no patient survival benefit.20 Prior to determining treatment, the lesion’s histologic diagnosis should be established (generally with permanent paraffin-embedded sections). The standard surgical treatment for BCC, SCC and sebaceous cell is Mohs with intraoperative frozen sections.19,20,34 Mohs is also used for many non-melanoma tumors and in situations where lesions may have aggressive growth patterns or when tissue conservation is critical.16 Its use for Merkel cell and melanoma is controversial.16 The absence of subcutaneous fat in the eyelid complicates surgical reconstruction concerns. The delicacy of the periorbital area frequently requires an interdisciplinary approach that includes both a Mohs surgeon and oculo or facial plastic surgeon.25 Adjunct therapies to Mohs include topical chemotherapy for BCC lesions for which surgical excision is not appropriate or those with unclear margins.20 Cryotherapy or topical chemotherapy are options for sebaceous cell lesions with pagetoid spread.24 Radiotherapy, an adjunct therapy for MCC, can lower the rates of recurrence.19 Photodynamic therapy with topical 5-aminolevulinic acid is a non-surgical alternative for SCC.19 A better understanding of genetic pathways for mutation has led to targeted immunotherapies. BCC studies have used medications such as vismodegib and imiquimod. Imiquimod may also have applications in the treatment of melanoma.20 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors are under investigation for SCC.20 These promising treatments are likely to have less systemic toxicity. When comanaging these post-op patients, optometrists are likely to encounter complications ranging from ptosis and trichiasis to ectropion and corneal ulcers.20 Patients must be followed for signs of recurrence. |

Malignant melanoma. These account for fewer than 1% of eyelid malignancies.21 The lesions arise de novo or from pre-malignancies such as congenital nevi, dysplastic nevi or lentigo maligna (melanoma in situ, also known as Hutchinson’s freckle).20 Eyelid melanomas can present with or without pigment, complicating accurate diagnosis. Therefore, clinicians should consider the ABCDEs of melanoma (Table 1). Sun exposure to fair skin puts patients at greatest risk, with the lower eyelid being the most common location.31 Superficial spreading lesions have a better prognosis than the nodular type.32 Because eyelid melanoma’s behavior is consistent with cutaneous melanomas, a significant risk of lymph node metastasis exists.3

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). This is another rare eyelid malignancy that originates from neuroendocrine cells.20 Females are more apt to be affected in their 70s and 80s.19 Risk factors include sun exposure, immune suppression and polyomavirus. MCCs are solitary nodules with or without telangiectatic vessels. The nodules are painless and appear purple or reddish in color.20 Additional signs may include ulceration and madarosis. The mnemonic “AEIOU” can help to recall features consistent with MCC (Table 2).35

Differential diagnoses for MCC include chalazion, keratoacanthoma, SCC, BCC and sebaceous cell carcinoma.34 These lesions grow rapidly over weeks to months, and two-thirds of Merkel cell tumors metastasize to the lymph nodes either at diagnosis or within 18 months.19,20 Research suggests 21% of cases recur.35

Optometrists play a critical role in detecting and clinically deciphering between benign and concerning periocular lesions. Clinicians should be familiar with each lesion’s typical features, risk factors, referral timeline, general treatments and outcomes to providing high quality patient care.

Dr. Weidmayer practices at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System in Ann Arbor, MI.

Dr. McGinty-Tauren practices at the Battle Creek VA Medical Center in Battle Creek, MI.

Contents in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

1. Yu S-S, Zhao Y, Zhao H, et al. A retrospective study of 2228 cases with eyelid tumors. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(11):1835-41. 2. Baek SH, Chi MJ. Clinical analysis of benign eyelid and conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220:43-51. 3. Suimon Y, Kase S, Ishijima K, et al. Clinicopathological features of cystic lesions in the eyelid. Biomed Rep. 2019;10(2):92-96. 4. Wu AY, Gervasio KA, Gergoudis KN, et al. Conservative therapy for chalazia: is it really effective? Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:e503-e509. 5. Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018. 6. López-Ríos F, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Castaño E, Benito A. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a cutaneous epidermal cyst: case report and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21(2):174–77. 7. Singh AD, McCloskey L, Parsons MA, et al. Eccrine hidrocystoma of the eyelid. Eye (Lond). 2005;19(1):77–9. 8. Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, Viana GA. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(1):134-6. 9. Gupta S, Handa U, Handa S, Mohan H. The efficacy of electrosurgery and excision in treating patients with multiple apocrine hidrocystomas. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(4):382-4. 10. Wollina U. Seborrheic keratoses - the most common benign skin tumor of humans. Clinical presentation and an update on pathogenesis and treatment options. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(11):2270-75. 11. Werner RN, Sammain A, Erdmann R, et al. The natural history of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(3):502-18. 12. Richard MA, Amici JM, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Management of actinic keratosis at specific body sites in patients at high risk of carcinoma lesions: expert consensus from the AKTeam of expert clinicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;32(3):339-46. 13. Venna SS, Lee D, Stadecker MJ, et al. Clinical recognition of actinic keratoses in a high-risk population: How good are we? Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(4):507-9. 14. Marks R, Foley P, Goodman G, et al. Spontaneous remission of solar keratoses: the case for conservative management. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115(6):649-55. 15. Lagler CNP, Freitag SK. Management of periocular actinic keratosis: a review of practice patterns among ophthalmic plastic surgeons. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2012;28(4):277-81. 16. Finley EM. The principles of Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous neoplasia. Ochsner J. 2003;5(2):22-33. 17. Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, James CL, et al. Periocular keratoacanthoma: can we always rely on the clinical diagnosis? Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(9):1201-4. 18. Griffiths RW. Keratoacanthoma observed. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(6):485-501. 19. Bernardini F. Management of malignant and benign eyelid lesions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:480-84. 20. Silverman N, Shinder R. What’s new in eyelid tumors. Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2017;6(2):143-152. 21. Pe’er J. Pathology of eyelid tumors. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(3):177-90. 22. Yin V, Merritt H, Sniegowski M, Esmaeli B. Eyelid and ocular surface carcinoma: Diagnosis and management. Clinics in Dermatology. 2015;33:159-69. 23. Cook B, Bartley G. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(4):746-50. 24. Ling M, Silkiss R. Diagnosis and management of sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid. Eyenet. Ophthalmic Pearls. Oncology. 25. Weesie F, Naus N, Hollestein L, et al. Recurrence of periocular basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(5):1176-82. 26. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15(3):315-28. 27. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15(4):424-31. 28. Neubert T, Lehmann P. Bowen’s disease – a review of newer treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(5):1085-95. 29. Kao GF. Carcinoma arising in Bowen’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(10):1124-6. 30. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976-90. 31. Chan F, O’Donnell B, Whitehead K, et al. Treatment and outcomes of malignant melanoma of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(1):187-92. 32. Garner A, Koornneef L, Levene A, Collin J. Malignant melanoma of the eyelid skin: histopathology and behavior. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69(3):180-86. 33. Shields C, Shields J. Ocular melanoma: relatively rare but requiring respect. Clinics in Dermatology. 2009;27(1):122-33. 34. Huang D, Silkiss R. Diagnosis and management of Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Eyenet. 2015 Jan:37-39. 35. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(3):375-81. |