The maiden battle to gain prescription rights was first won by optometrists in West Virginia in 1976. Other states have all followed suit, but with these privileges often come challenges.

From insurance coverage strangleholds to deciding whether a patient with financial constraints will do as well on a more affordable generic (instead of the brand name you’d prefer), optometrists often face difficult prescribing decisions even before they pick up their Rx pad.

“The fact that many of the branded prescriptions we typically write are becoming more and more difficult to obtain for a patient because of medical insurance and pharmacy plans is a major problem,” says optometrist Ben Gaddie of Louisville, Ky. “We’re often advised to use a drug perhaps two or three generations old that just doesn’t get the job done. And when the patient fails on it, then we have to prescribe multiple drugs in that category or in multiple categories just to cover the original drug we prescribed. And when we can actually get a drug that is covered, sometimes it’s financially out of reach for the patient.”

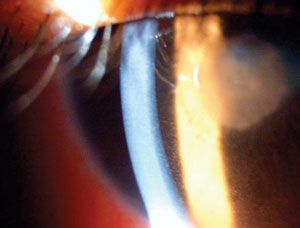

| |

| For a serious condition such as uveitis, many doctors will insist on a brand-name medication—no generic substition allowed. Photo: Paul M. Karpecki, OD. |

This article looks at some typical and not-so-typical modern day prescribing challenges, and how to tackle them.

Challenge #1: Brand name or generic?

The idea that a generic drug is an adequate Plan B for a brand-name drug is still hotly debated.

The FDA requires that generic drug manufacturers demonstrate bioequivalence to the branded drug, so the generic must contain the same concentration of active ingredients as the branded drug’s formulation. But other variations are permitted in the generic, such as inactive ingredients and preservatives, which can alter characteristics of the medication and change the efficacy and side effects of the drug.

“As a general rule, the doctor should always prescribe the most appropriate medication for each patient’s condition,” says optometrist Jimmy Bartlett of Birmingham, Ala.

In practice, however, managed care, insurance and economic issues must be considered, and these often supersede the theoretical optimum, Dr. Bartlett adds.

“We always want to use what is in the best interest of each patient, and therapeutic care may entail using a somewhat less desirable generic substitute, particularly if the alternative is no therapeutic care at all,” he says. “Unfortunately, in this age of managed care, we are forced to have these discussions with the patient as a matter of routine, whereas in years past these issues required only an occasional discussion in problematic situations.”

Here are some considerations to keep in mind when deciding whether to prescribe a brand-name drug or a generic:

• Generics are not necessarily cheaper. In some cases, generic alternatives are not a lower-cost option. In fact, Freehold, NJ, optometrist William Potter says some generic prices are “through the ceiling.”

| Prescribing With Hands Tied What’s it like to practice in a state that still has restrictive prescribing privileges? For optometrist Dawn Chivers, who practices in New York—one of the few states that allows ODs to treat patients only with topical or OTC meds—the current prescribing limitations impact her patients and her practice, especially when a patient is sitting in her chair on weekends or in the evening when most primary care physicians and ophthalmologists don’t have office hours. If a patient has an acute condition, needs an oral medication and it’s a Saturday, chances are they’ll have to go to the emergency room. This scenario can often lead to delayed treatment, increased cost to the patient and even incorrect treatment, she adds. Dr. Chivers, who is the vice president of the New York State Optometric Association (NYSOA), recently sent a patient to the ER on a Friday afternoon for herpes keratitis with a note with the correct diagnosis and recommended course of treatment for oral acyclovir. The patient came back to Dr. Chivers’ office first thing Monday morning with extreme discomfort and declining vision. The ER doctor had prescribed topical Vigamox (moxifloxacin, Alcon) instead of Dr. Chivers’ recommendation. The patient had a $50 co-pay at the emergency room, waited four hours and was given a prescription for a drop that cost about $100, all to have her condition worsen. “The patient now has a central scar on her cornea and reduced vision in that eye,” Dr. Chivers adds. Since 1998, New York ODs have been fighting to expand their oral prescribing privileges. On the upside, Dr. Chivers says the NYSOA has made significant strides over the past year in building support in the state legislature regarding oral prescriptive authority. “We believe 2015 could be the year we are finally able to see this common sense legislation enacted into law,” she says. |

“To some degree, it’s an upside-down world,” Dr. Potter says.

Dr. Potter says he writes a fair amount of prescriptions for Tobradex ST (tobramycin 0.3%/dexamethasone 0.05%, Alcon) and gives his patients coupons to help offset the price, so the final cost of the brand-name medication is approximately $40 to $50.

“We wrote for Tobradex generically a few months ago,” Dr. Potter says. “The patient called from the pharmacy and said, ‘I can’t do this. This generic drug costs $100.’ Now remember, this is a drug that’s been on the market for 25 years, and it’s been generic for three years. We called the pharmacist who told us, ‘If it wasn’t for the patient’s insurance, generic Tobradex would have cost $250.’ And that’s for a little, ‘white bottle’ legacy drug. This is the kind of thing we’re up against.”

• Assess the clinical need. Looking at the patient’s clinical condition, when should an OD write for brand name only?

“Some brands trump generics, but not necessarily in every patient,” says Jill Autry, OD, RPh, of Houston.

For example, Dr. Autry generally prescribes brand-name Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate 1%, Allergan) rather than the generic equivalent. “It is fairly well established that the Pred Forte brand has better suspension qualities than the generic, especially with a more severe pathology,” she says. “In those cases, I write for branded Pred Forte, but I also tell the patient that I’m writing for brand name only and they should not allow the pharmacist to substitute.”

Dr. Autry reinforces to patients that the brand name should be visible on the side of the bottle, and she stresses they should not leave the pharmacy unless they have the right medication. “I don’t really get any pushback because of the way I present it to the patient, and pharmacies in the Houston area often carry the brand.”

When considering a brand name or generic, Dr. Gaddie first looks at the urgency or degree of the patient’s condition. If a patient has a very aggressive uveitis, for instance, he prescribes a brand-name steroid and not a generic.

“We know in the steroid class of medication, the gold standard has always been Pred Forte. There are many generic drug manufacturers, and we know from studies the generics aren’t nearly as efficacious as the branded drug,” Dr. Gaddie says.

This has much to do with the particle size of the steroid molecule. Because the steroid is a suspension, the patient has to shake the bottle in order to get the concentration of the drug correct. But many patients just don’t shake medications, he adds.

Additionally, the size of the actual steroid particle can make an impact on the solubility of the drug and therefore affect how well it treats the inflammation, he adds. “If I’m treating someone with just a mild ocular surface problem, a generic steroid may be fine. But if I’m treating someone with a serious inflammatory condition, then I really feel like the branded drugs work better and are quicker and safer than the generic drugs.”

Similarly, if a patient has a low-risk bacterial conjunctivitis, Dr. Gaddie will consider a generic antibiotic because most of the bacterial strains that cause conjunctivitis are fairly responsive to most generic topical antibiotics, he says.

Looking at glaucoma drugs, Xalatan (latanoprost, Pfizer) now has a generic equivalent that is produced by numerous manufacturers in various countries. Thus, a patient may not be given the same generic version when refilling the Rx. Dr. Gaddie says that some patients do well on the generic, but other times, when a patient obtains a different generic version of latanoprost, it doesn’t work as well, he says.

“If I had a choice, I would want every patient to be on branded glaucoma drugs,” Dr. Gaddie says. “If a generic doesn’t work as well, then we have to add a second medication or maybe a third medication just to get the pressure down to where it needs to be than if we used a branded prostaglandin to start with. It costs the system more money, there are potentially more side effects for the patient, and what you have is a more complex treatment regimen because it takes two to three drugs to have the efficacy of one of the branded glaucoma prostaglandins.”

• Fight pharmacy substitution. Optometrist Melvin Friedman of Memphis, Tenn., requires his patients to sign an Rx waiver citing they have been told the difference between generic vs. brand-name drugs.

| |

| If the patient’s insurance won’t cover the medication you prescribe for this corneal ulcer, or if the drug is in short supply, have a second option in mind. Photo: Aaron Bronner, OD. |

He also trains his staff to handle calls from pharmacists who want to substitute with a generic. For example, Dr. Friedman recently wrote a prescription for Besivance (besifloxacin, Bausch + Lomb) and the pharmacist called the practice to see if generic ciprofloxacin could be used as a substitute, but the staff refused. Dr. Friedman called the pharmacist directly and told him ciprofloxacin and Besivance are not equivalent. The pharmacist blamed the insurance company for the switch, he says.

“I told the pharmacist if he ever put my patient at risk again, I would report him and his staff to the pharmacy board,” Dr. Friedman says. “Not enough physicians are willing to take a stand, and that’s a problem.”

• Find a solution. But what happens if the patient can’t afford the brand-name drug you prescribe? Dr. Autry always tells the patient what she thinks is the best treatment option available.

“If it’s not doable, then certainly we need to talk and see if there is a combination or a different medication that will work,” she says. “I tell this to the patient on the front end because $250 a month can be a big difference from $50 a month For some people $50 is a lot, so you have to make a judgment call. In these cases, I’ll say, ‘There is another medication I can try, and we’ll see how it goes.’ And the patient will often say, ‘Well, $50 I can do.’”

If the brand-name drug is the best treatment option, optometrists can often help lessen the burden of the cost by offering manufacturers’ coupons or advising about patient assistance programs they may be eligible for. “I can’t tell you how many times patients don’t know these options are available,” Dr. Friedman says. “If the patient can’t afford it, we can help.”

Challenge #2: How do you deal with state restrictions or limited supply?

While a few states don’t allow ODs to prescribe oral meds (see “Prescribing With Hands Tied”), optometrists from these states should already have established working relationships with primary care physicians or ophthalmologists who can assist with prescribing needs, Dr. Bartlett says. ODs who work in the same office with ophthalmologists should have established “standing orders” whereby prescriptions can be written, e-prescribed or called in to the pharmacy on behalf of the patient but under the order (and thus shared legal responsibility) of the MD.

| |

| If a needed medication isn’t available topically—such as fortified ceftazidime for gram-negative coverage against Pseudomonas—consider special ordering it from a compounding pharmacy. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

“It is much more cumbersome to establish relationships with physicians in other offices, but this was routinely done in most states prior to the enabling of statutory privileges to allow independent prescribing by optometrists,” Dr. Bartlett says.

In the event of drug shortage or if a pharmacy doesn’t immediately have the drug you want, always have a work-around, the experts say. For example, if a certain fixed-combination antibiotic/steroid is not available, prescribe a combination using a desirable topical antibiotic along with a separate topical steroid, Dr. Bartlett says.

When AzaSite (azithromycin, Akorn) was in limited supply to treat blepharitis off-label, Dr. Autry instead prescribed oral doxycycline or oral azithromycin. She says these drugs have worked well as a substitute, and they are generally cheaper.

Also in the case of blepharitis, Dr. Potter has three alternate options ahead of time—erythromycin ointment, oral doxycycline or azithromycin—if his preferred drug is unavailable.

“Really, for any medicine you prescribe, you have to be ready to have a work-around,” says optometrist Jeffry Gerson of Kansas City, Kan. “Although you always have a best choice in mind, you also need to have a second choice—whether there’s a shortage and lack of availability, or because the patient has a financial issue, or if the patient lives in a rural area and the pharmacy doesn’t have what you want and the pharmacist can’t get the medication for a few days.”

For example, if a patient has a corneal ulcer, Dr. Gerson’s first option is Zymaxid (gatifloxacin 0.5%, Allergan). If the pharmacy doesn’t have that in stock, he’s ready with his second choices, Moxeza (moxifloxacin 0.5%, Alcon) or Besivance. If neither of those is available, Dr. Gerson would ask what is in stock in the same drug class, followed by considering a generic that would be a close equivalent.

Challenge #3: How do you effectively manage patients who have allergies, are taking other medications for concomitant disease, or are nursing/pregnant?

Know the issues that may arise from the patient’s medical history, such as:

• Managing medication allergies. A careful medication history almost always reveals the class of medications to which the patient may be allergic or sensitive, says Dr. Bartlett. It is usually possible to select an alternate drug class that can be safely prescribed, he adds.

| The ‘Non-Prescribing’ and Rx Switch Challenge What do you do when a patient assumes he or she needs a prescription and expects you to get out your Rx pad before leaving the office? This non-prescribing challenge is a common one, Dr. Gerson says. “If someone comes in with a watery, red eye that looks viral, it’s a challenge to satisfy the patient without an antibiotic fix.” In this case, explain that the condition is viral like the flu. And, in the same way an oral antibiotic is ineffective against the flu, an antibiotic eye drop won’t help either, Dr. Gerson says. Another Rx conundrum is when an ER or primary care doctor refers a patient to you, and the patient has already purchased a drug the referring doctor has prescribed that you don’t think will work. “It’s even more of a challenge if you want to prescribe them a brand drug, but the prescription they got from the emergency room cost $4 and the drug you want them to buy instead is $60,” Dr. Gerson says. If the patient has already started the other medication and has had no improvement by the time he or she comes to see you, the discussion is easier. However, it’s more difficult if the patient has been on the other drug for only a day or two. “It’s a delicate situation,” Dr. Gerson says. “You don’t want to discredit the other physician who saw them. You need to tell the patient, ‘I know the other doctor gave you a prescription for an antibiotic, but I would really like you to try this because I think it is going to work much better.’ It’s important to explain and be up front with the patient.” |

Dr. Gaddie finds many of his glaucoma patients can become allergic to brimonidine. The drug, developed in the late 1990s, was originally formulated at 0.2%.“There was a 15% to 20% allergy rate for glaucoma patients taking this drug,” Dr. Gaddie says. Allergan subsequently lowered the concentration but maintained the drug’s efficacy, and the allergy problem was for the most part mitigated, he says.

However, that original 0.2% concentration was used in the development of Combigan (brimonidine 0.2%/timolol 0.5%, Allergan) and Simbrinza (brinzolamide 1%/ brimonidine 0.2%, Alcon).

“The problem is the development of this combo agent started before the newer concentration of brimonidine was available, so these two combination medicines contain the higher percentage formulation of brimonidine and its higher rate of allergy,” Dr. Gaddie says. “So for patients who are allergic, it knocks out two or three glaucoma medications.”

In such cases, Dr. Gaddie tries a different class of medications or even considers laser trabeculoplasty as an option.

• Cautious concomitant prescribing. Doctors often treat patients for ophthalmic conditions who are also on other concomitant medications for systemic diseases, he adds. For example, topical beta-blockers are staple glaucoma drugs, but the patient may also be taking oral beta-blockers for their blood pressure. Studies have found the concomitant use of topical and oral beta-blocker drugs reduces the efficacy of both.1

Other patients have systemic medical conditions such as asthma, COPD, heart failure and arrhythmias, so the optometrist needs to aware of the patient’s health history and not put the patient at cardiac or pulmonary risk when using a beta-blocker or alpha agonists, for example, Dr. Gaddie says.

“You really need to stay on top of the literature to recognize the trade names of certain drugs,” he says. “There are newer drugs that maybe we weren’t exposed to when we were in optometry school, but it’s still our responsibility to stay up-to-date and make sure there are no contraindications to any topical medications.”

• Prescribing for pregnant/nursing patients. Another challenge you face is managing pregnant or nursing patients. “Prescribing during pregnancy is always a risk-benefit consideration,” Dr. Bartlett says.

| |

| Prescribing a drug for children, such as amoxicillin for a case of preseptal cellulitis, requires specific dosing based on the child’s age and weight. Photo: Leonard J. Press, OD. |

Although the general rule is to avoid medications during pregnancy, this is often not practical, especially for chronic conditions such as allergies, glaucoma or ocular hypertension, he adds. Doctors may be able to select a drug in the comparatively safer FDA pregnancy category B, Dr. Bartlett says. When drugs in the more risky category C (such as topical steroids) are needed, the patient can be instructed on the technique of nasolacrimal occlusion for one to two minutes after each drop instillation.

Dr. Gaddie is currently managing a pregnant 32-year-old patient diagnosed with glaucoma. The patient is three months pregnant and planning to breastfeed. “All glaucoma medications are really contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding, so I have to consider whether this patient is going to have significant vision loss or potentially go blind in a year-and-a-half and weigh that against the risk to the developing baby if the mother takes the medication.”

In this case, Dr. Gaddie is working closely with the patient’s obstetrician to determine the best treatment decision.

Challenge #4: When should you consider compounding medications for off-label use?

Compounding ophthalmic medications may be a necessity if you need a different strength, dosage, formulation or ingredients.

Dr. Autry frequently prescribes compounded drugs, most commonly to increase the concentration of medications to treat corneal ulcers.

She also turns to compounding if a medication isn’t available topically. For example, because vancomycin is not available in a topical form for Staph. coverage in severe corneal ulcers, compounding is an option. Another example is fortified, compounded ceftazidime for gram-negative coverage against Pseudomonas.

Additionally, if a patient with ocular surface disease needs more than Restasis (cyclosporine, Allergan), a compounding pharmacist can create cyclosporine ophthalmic ointment, autologous serum drops, tacrolimus solution or ointment, or albumin drops, she says.

| Body Weight (kg) | Volume of Augmentin ES-600 Powder for Oral Suspension providing 90mg/kg/day | |

| 8 | 3.0mL twice daily | |

| 12 | 4.5mL twice daily | |

| 16 | 6.0mL twice daily | |

| 20 | 7.5mL twice daily | |

| 24 | 9.0mL twice daily | |

| 28 | 10.5mL twice daily | |

| 32 | 12.0mL twice daily | |

| 36 | 13.5mL twice daily |

Your pharmacist down the street is not necessarily going to be able to compound ocular preparations from scratch, so find a good compounding pharmacist ahead of time before a patient walks through the door, Dr. Autry suggests. (To find one, visit: www.pccarx.com/contact-us/find-a-compounder.)

One caveat about compounding medications is whether insurance will pay for it. “Once you get into these homebrews, insurance is going to be a question,” Dr. Potter says. “It’s never going to be a question on a corneal ulcer, but if I say, ‘I think the Restasis should be twice as strong and I think the insurance should pay for it,’ the answer is often no.”

Challenge #5: How do you prescribe for pediatric patients?

“Many practitioners are uncomfortable with using systemic medications in children, but this is simply a matter of gaining clinical experience,” Dr. Bartlett says. Get started by prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics for internal hordeolum and preseptal cellulitis in children, he suggests.

“Dosage calculations are typically straightforward, and most of these medications have a wide range of safety,” he says.

Dr. Autry also suggests working up a pediatric dosing chart to have on-hand in the office. This resource could include the proper dosing of a typical drug you’d prescribe, such as amoxicillin or azithromycin, based on the child’s age and weight.

She provides this example:

One of the key challenges Dr. Gaddie sees: optometrists not gaining confidence in prescribing while being exposed to more ophthalmic diseases.

“Optometrists may have all the clinical knowledge in the world, but they still can be hesitant to prescribe,” he says. “I encourage doctors to start prescribing with low-risk conditions as a stepping stone to managing more complicated ocular diseases. Once optometrists start treating conditions such as allergy and dry eye, it gives them the confidence to tackle conditions such as glaucoma.”

1. Schuman JS. Effects of systemic beta-blocker therapy on the efficacy and safety of topical brimonidine and timolol. Brimonidine Study Groups 1 and 2. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1171-7.