|

It’s not often that you see heterochromia iridis, but when you do, you should also be on the lookout for depigmented hair, a displaced medial canthus and even congenital hearing loss. That’s because heterochromia iridis—along with these other findings—is a classic sign of a rare systemic condition, Waardenburg syndrome (WS).

This hereditary group of conditions, first described in 1951, is rare, affecting an estimated one in 40,000 people, and accounts for 2% to 5% of all cases of congenital hearing loss.1-3 It may be inherited in an autosomal dominant (most commonly) or autosomal recessive manner, although signs and symptoms often vary between and even within families. Common features include congenital sensorineural deafness; pale blue eyes, different colored eyes, or two colors within one eye; a white forelock (hair just above the forehead); or early graying of scalp hair before age 30. Various other systemic signs may also be present, from chronic constipation to slightly decreased intellectual functioning.1,2

While WS requires a thorough case history to confirm the diagnosis, the ocular features are easily recognizable to the OD, providing a clue to the underlying diagnosis.

|

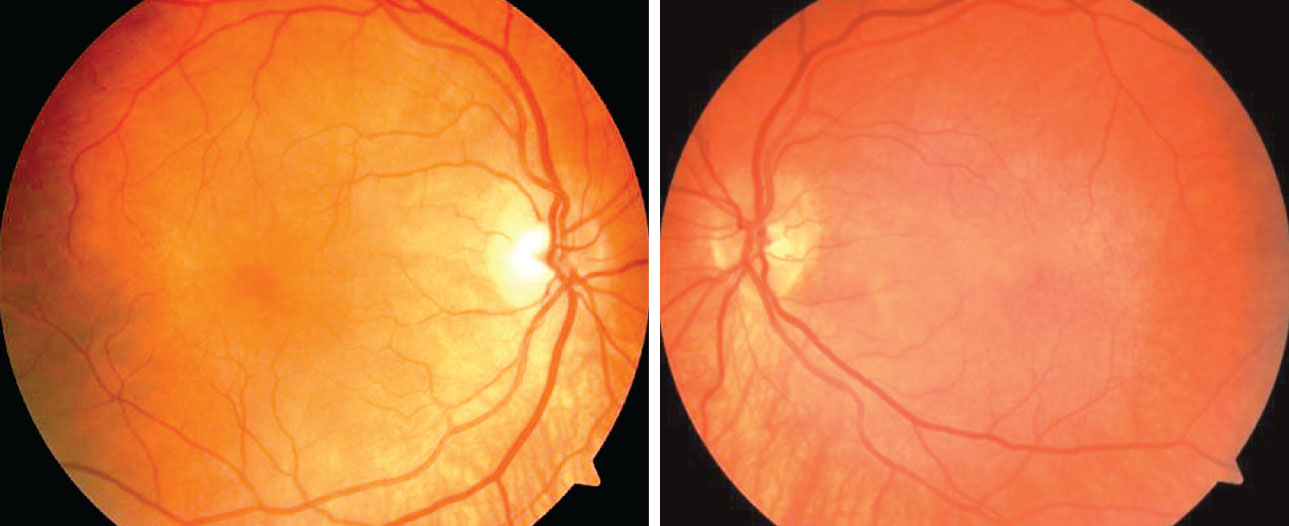

| Fig. 1. The patient’s dilated fundus exam revealed a post-equatorial hypopigmented choroid as well as choroidal folds in the right and left eyes. Click image to enlarge. |

The Choroid

Research shows mutations in at least six different genes cause WS, including EDN3, EDNRB, MITF, PAX3, SNAI2 and SOX10.2-4 All of these genes are involved in the development of several cell types, including pigment-producing melanocytes.2-4

In the eye, melanocytes are responsible for the pigment in the choroid and the stroma of the iris and ciliary body. Uveal melanocytes are developed from the neural crest, the same origin as the melanocytes in skin and hair.5

In addition to iris pigmentary abnormalities, careful inspection can reveal posterior uveal pigmentary anomalies. One study observed broad areas of choroidal hypopigmentation with WS, and foveal OCT revealed that the hypopigmented choroid was slightly (19%) thinner compared with the normal opposite subfoveal counterpart.5

|

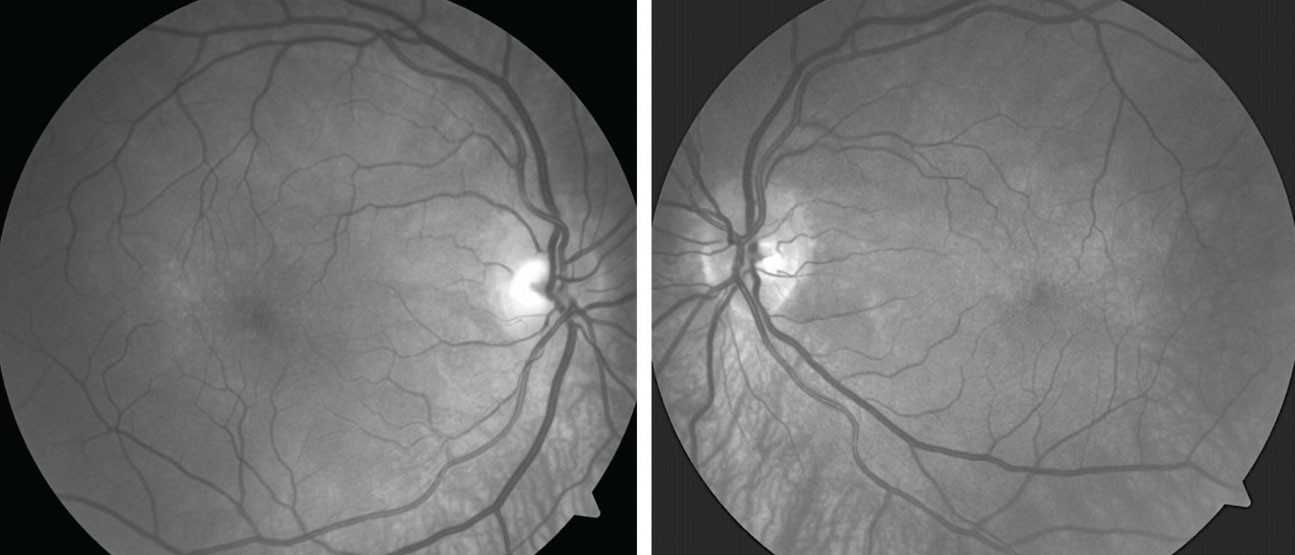

| Fig. 2. Red-free images show broad areas of choroidal hypopigmentation, most prominent in the area inferior to each optic disc. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis and Management

WS is classified into four subtypes based on the presence of certain features and the genetic cause, with types I and II being the most common.2-4 In 1992, the Waardenburg Consortium proposed diagnostic standards, which include both major and minor criteria. A diagnosis of type I must meet two major, or one major and two minor criteria:2,4,6

Major criteria:

- Congenital sensorineural hearing loss

- Iris pigmentary abnormality, such as heterochromia iridis (complete, partial or segmental); pale blue eyes (isohypochromia iridis); or pigmentary abnormalities of the fundus (choroid)

- Abnormalities of hair pigmentation, such as white forelock, or loss of hair color

- Dystopia canthorum—lateral displacement of inner canthi (in types I and III only)

- A first degree relative with WS

Minor criteria:

- Leukoderma (white patches of skin) present from birth

- Synophrys (connected eyebrows) or medial eyebrow flare

- Broad or high nasal bridge

- Hypoplasia of the nostrils

- Premature gray hair (younger than age 30)

WS type II has features similar to type I, but with no signs of dystopia canthorum. Type III is additionally characterized by musculoskeletal abnormalities such as muscle hypoplasia; flexion contractures (inability to straighten joints); or syndactyly (webbed or fused fingers or toes). Type IV has similar features to type II, but with Hirschsprung disease (a condition resulting from missing nerve cells in the muscles of part or all of the large intestine).2,4,6

Because no specific treatment exists for this condition, management is directed toward specific symptoms and signs. Optimal care often requires the coordinated efforts of a team of medical professionals, such as optometrists, dermatologists, hearing specialists, orthopedists and gastroenterologists. Patients with chronic constipation are often prescribed special diets and medications to promote gastrointestinal health. All patients with WS require close monitoring for hearing loss and an annual comprehensive ophthalmic workup.2,4,6,7

|

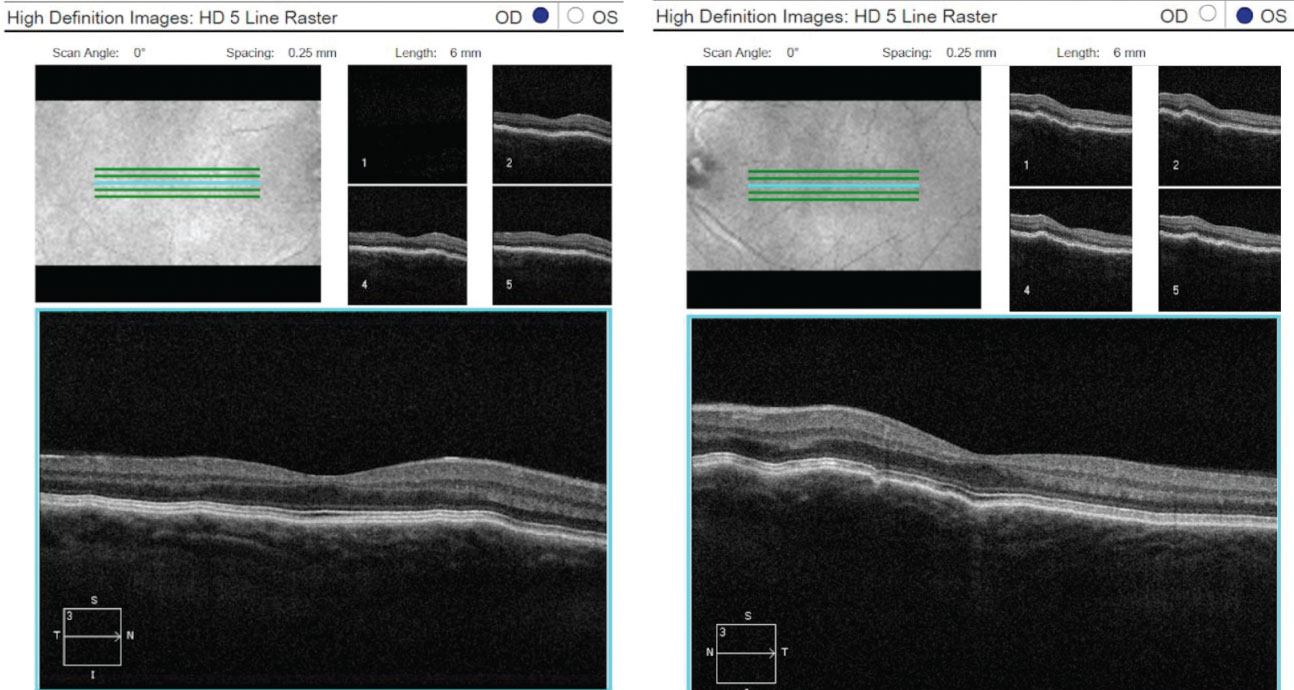

| Fig. 3. OCT 5-line raster scans of both eyes demonstrated a normal retina, but slight thinning of choroidal tissue and subtle choroidal folds. Click image to enlarge. |

Case Report

By Jeanne I. Ruff, OD

A 43-year-old Caucasian female presented with complaints of near blur and a history of WS type II. Her entering corrected distance acuities measured 20/20-2 OD and OS. Manifest refraction was +2.50 -1.50 003 OD and +2.50 -0.75 060 OS. She had a plus build-up of +1.50D OU, and her near visual acuities were 20/20 OU.

Biomicroscopy revealed iris herterochromia OD and bilateral iris transillumination defects, greater in the OS. No pigment cells on the corneal endothelium were observed in either eye.

Dilated funduscopy was remarkable for a subtle, wave-like appearance of the posterior pole OS > OD, consistent with choroidal folds.

Fundus photography documented a post-equatorial hypopigmented choroid in the right and left eyes (Figures 1 and 2). OCT demonstrated normal retinas and slight thinning of choroidal tissue in both eyes, along with subtle choroidal folds (Figure 3). Frequency doubling technology perimetry was normal OD, but revealed central deficits with some foveal sparing OS.

We relayed these findings to the patient and her primary care provider and prescribed a reading addition of +1.50 D OU to alleviate the near blur. She was scheduled for ocular echography to rule out other causes of choroidal folds, which are most likely due to the hyperopia. She was also educated on the need for semi-annual follow-up.

Dr. Ruff earned her Doctor of Optometry from Nova Southeastern University. She practices in the Williamsburg, VA area, with an emphasis on full-scope care and advanced diagnostic technology.

1. Waardenburg PJ. A new syndrome combining developmental anomalies of the eyelids, eyebrows and nose root with pigmentary defects of the iris and head hair and with congenital deafness. Am J Hum Genet. 1951;3(3):195-253. 2. Newton VE. Clinical features of the Waardenburg syndromes. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;61:201-8. 3. Nayak CS, Isaacson G. Worldwide distribution of Waardenburg syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(9):817-20. 4. Zaman A, Capper R, Baddoo W. Waardenburg syndrome: more common than you think! Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40(1):44-8. 5. Dominic Tabor. Waardenburg syndrome. DermNet NZ. October 2015. www.dermnetnz.org/colour/waardenburg.html. Accessed August 1, 2019. 6. Hennekam, RCM, Krantz ID, Allanson JE, eds. Gorlin’s Syndromes of the Head and Neck. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:1369. 7. Shields CL, Nickerson SJ, Al-Dahmash S, Shields JA. Waardenburg syndrome: iris and choroidal hypopigmentation: findings on anterior and posterior segment imaging. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(9):1167-73. |