Scope Expansion SeriesRead the other articles featured in this series:

|

Optometrists typically know more, and are capable of doing more, than their state licensure will allow, a source of frustration for many and a setback to the efficient delivery of care in United States. Fortunately, especially in the last several years, the laws have been catching up. Multiple states have passed bills to allow more ODs than ever to practice to the full extent of their training and ability, and the momentum is clearly building.

Over the next four months, we’ll be digging into some of the newer optometric capabilities with advice from those who already have mastered the ins and outs.

Two practice privileges that a growing number of ODs in the country can embrace are (1) administering certain intralesional injections and (2) performing minor in-office procedures such as removal of lesions in and around the eye. Whether your state already allows you to perform these procedures, is in the process of trying to pass legislation or still has a ways to go to before scope expansion efforts come to fruition, this article will provide guidance on smoothly implementing these services into your practice when it’s inevitably time, as well as how to ensure each physician receives the proper training.

|

|

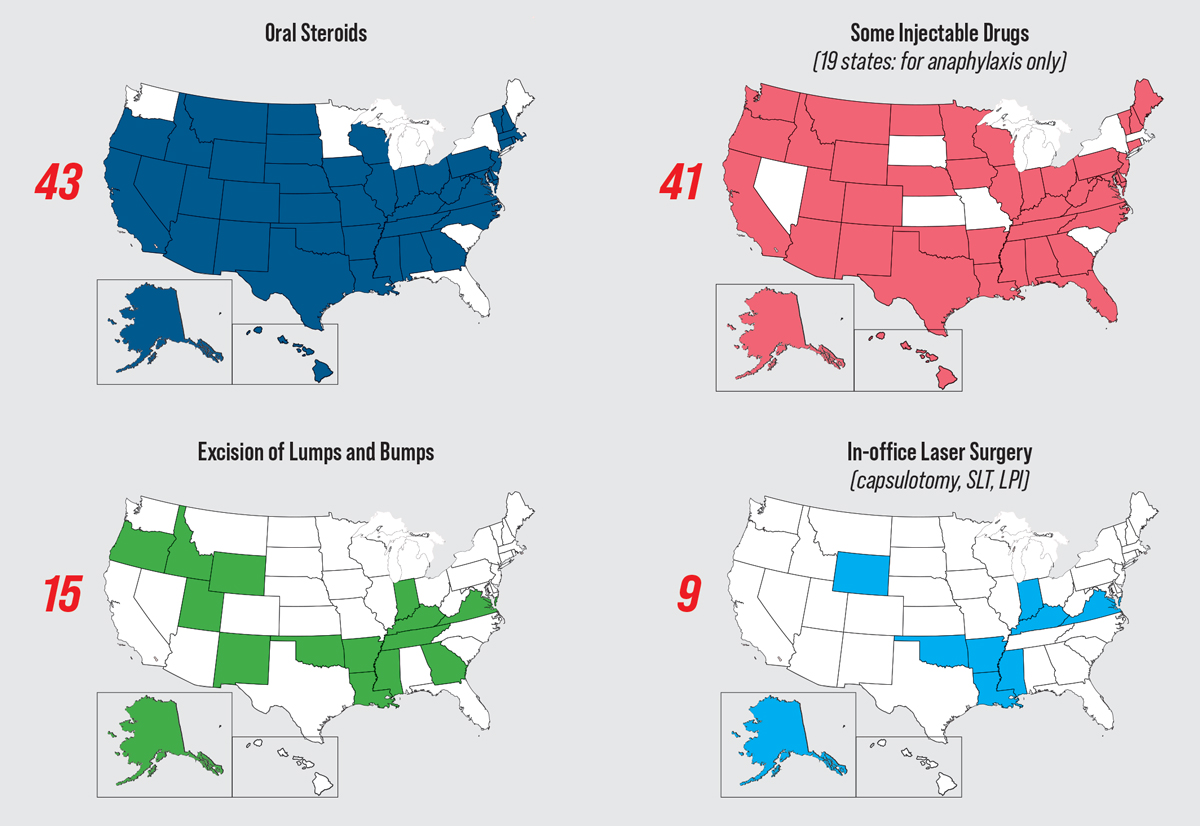

On the left, a patient receives an injection of lidocaine prior to removal of a lesion on the palpebral conjunctiva. On the right is the same patient immediately after injection with the bolus of anesthetic visible under the skin. All photos: Jackie Burress, OD, and Rodney Bendure, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Adding Services: The Logistics

Once a state expands its optometric scope of practice, there are many important considerations for practice owners to keep in mind when offering a new service to patients. The first—and arguably the most important—factor to consider is whether additional certification or education is required by that particular state’s law.

When offering lesion removal and injections, optometrists who have graduated within the last decade or two have often received the necessary training in school to conduct these procedures, notes Jackie Burress, OD, of Oklahoma, one of the earliest states to get on board with optometric scope expansion. However, for optometric physicians who are more seasoned in the field and did not receive this training as part of their education, additional certification or training courses may be obligatory. Specific requirements will vary from state to state, so it’s important to check with the board of optometry in your state before offering these procedures at your practice.

|

|

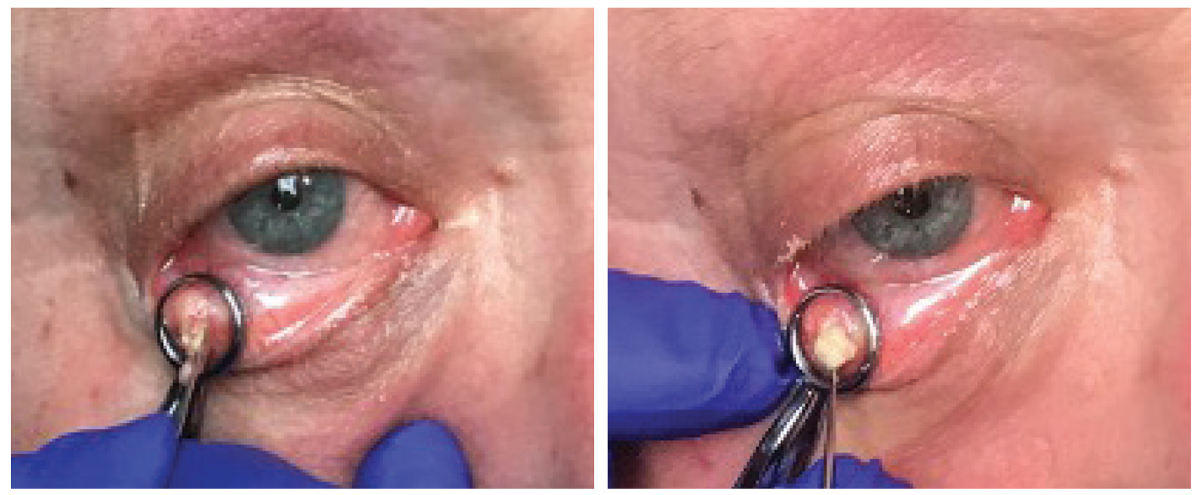

Before you perform the incision/curettage, the chalazion should be clamped to prevent the mass from moving during the procedure. Click image to enlarge. |

For optometrists who may not legally be required to undergo additional training but nevertheless want to refresh or enhance their clinical skills, shadowing a colleague who is already engaged in the service is a good way to start. Hands-on CE courses can also be helpful—not only to develop skills but also to better understand the tools as well as the practical components needed to expand clinical services.

Procedure set-up does take time, which could prove challenging in a busy practice. For this reason, Dr. Burress recommends dedicating them to a specific day. “This allows you to focus all of your attention on the procedures instead of fitting them in around standard appointments, which is more efficient and ensures optimal patient care,” she says.

Having the right tools at your disposal is also important (see “Prepping Your Clinic for Incisions and Injections,” on page 39, for a recommended list); however, don’t get caught up in the misconception that starting surgical procedures requires a huge financial investment, urges Richard Castillo, OD, DO, associate dean at Northeastern State University of Oklahoma (NSUOK) College of Optometry and a fierce advocate for optometric scope expansion. “Invest in yourself and your knowledge base,” he says. “Remember, you already bring a lot to the table. Your technical skillset and clinical understanding are what will help you successfully integrate these procedures into practice.” Dr. Castillo’s dual degrees in ophthalmology and optometry give him unique insights into the gaps between the two professions and how best to reconcile them.

For biopsies, you will need to work with your local lab to determine which preparations it will accept, according to Rodney Bendure, OD, another NSUOK optometrist. Upon request, the lab should provide the necessary specimen containers and requisition forms.

Billing and appropriate documentation is another logistical aspect of lesion removal and injections that ODs will have to adapt to in practice. Histopathological evaluation of lesions will be an additional cost to the patient, so it’s important to be transparent and let them know what to expect to avoid pained surprise. Dr. Bendure uses the phrase “abundance of caution” when discussing the need for labs or referrals with patients, particularly those who may be hesitant. Knowing and vocalizing the pros and cons of the various options will help patients feel more secure in your care, especially while these services are still being introduced to your practice.

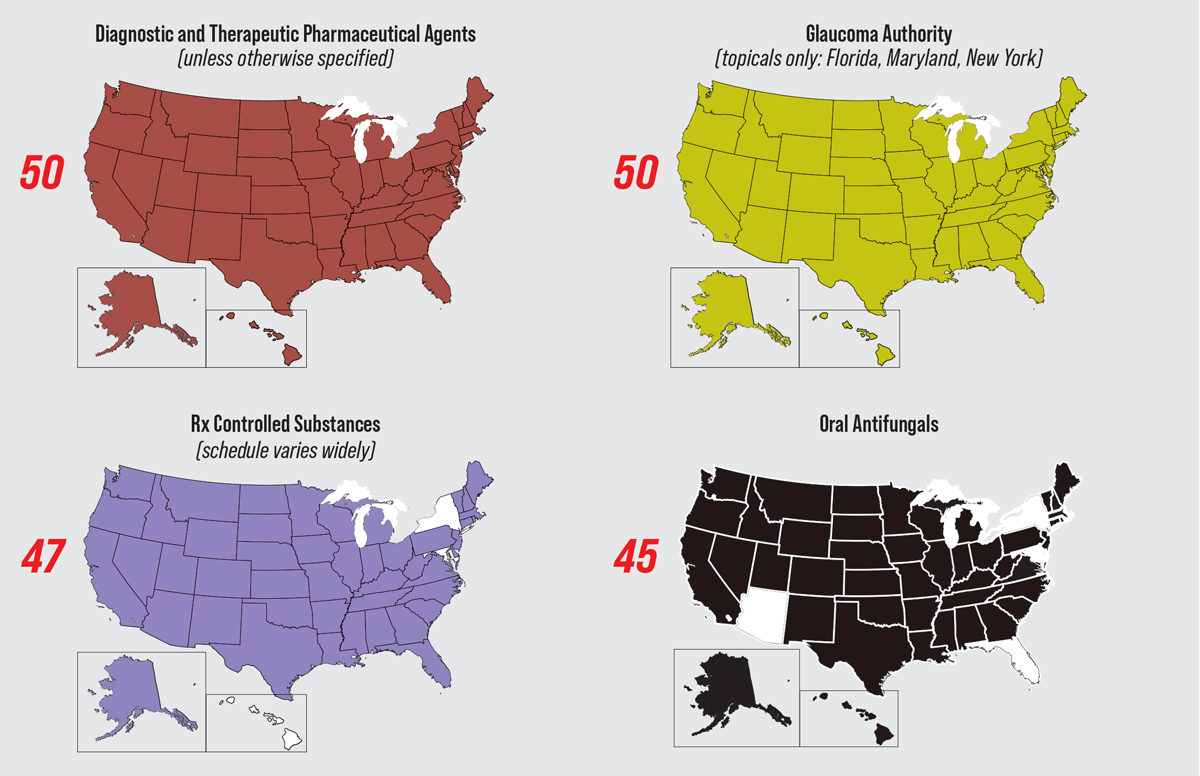

Status of Optometric Laws Across the United StatesFrom Rhode Island’s passage of the first diagnostic pharmaceutical agent law in 1971 to Virginia’s laser law, enacted just two months ago, the optometry profession has spent over 50 years fighting—and largely winning—battles in state legislatures to allow ODs to better capitalize on their expertise for the good of their communities. These victories have expanded access to eye care, lowered costs and increased patient convenience. Still, opposition has been and will continue to be fierce. A recent expansion bill was struck down in Alabama. Contact the AOA and/or your state association to find out how to help advocate for new privileges and obtain any necessary training.

|

Clinical Pearls for Incisions and Injections

Lesion removal and anterior segment injections encompass a number of different procedures, including intradermal injection for anesthesia, incision and curettage of chalazion and snip excisions, just to name a few. It is important to consult with your state board to determine which specific procedures are allowed under your state’s optometry laws.

As with any procedure, the clinical work begins with obtaining a thorough medical history and informed consent from the patient, explains Dr. Burress. This history should include past or present medical conditions, drugs and latex allergies and current medications, including both prescription and OTC.

Dr. Burress recommends paying close attention to anticoagulants, such as aspirin, NSAIDs, warfarin, heparin, dipyridamole and clopidogrel, since they can increase the risk of bleeding and prolong healing. Consulting with the patient’s primary care provider could help you decide if it is safe to temporarily stop the anticoagulant for lesion removal.

|

|

The left image shows granulomatous material extruding from the palpebral conjunctival lesion upon incision. On the right, curettage of the chalazion is expelling the material. Click image to enlarge. |

Prior to a procedure, Dr. Bendure makes sure to check patient vitals. “I had a young, healthy female in my chair about 12 years ago,” he recalls. “She wanted a few skin tags removed around her eyelids. I injected the areas to be treated with Xylocaine with epinephrine.” She was doing fine until he massaged the skin to disperse the medication.

“Apparently, I was too aggressive with the digital massage—she had a vasovagal response, turned pale green and passed out,” he continues. “Turns out getting her legs and feet elevated and putting a fan on her was all she needed.” Checking a patient’s vitals beforehand is always a good idea to help predict whether there is a possibility of complications during care that may perhaps be unrelated to the procedure itself.

When Corri Collins, OD, of Lexington, KY, sees a patient for lesion removal, she always takes a pre-op photo to allow for accurate documentation. This allows patients to have a clear, visual comparison of what their eye looked like before and after the procedure.

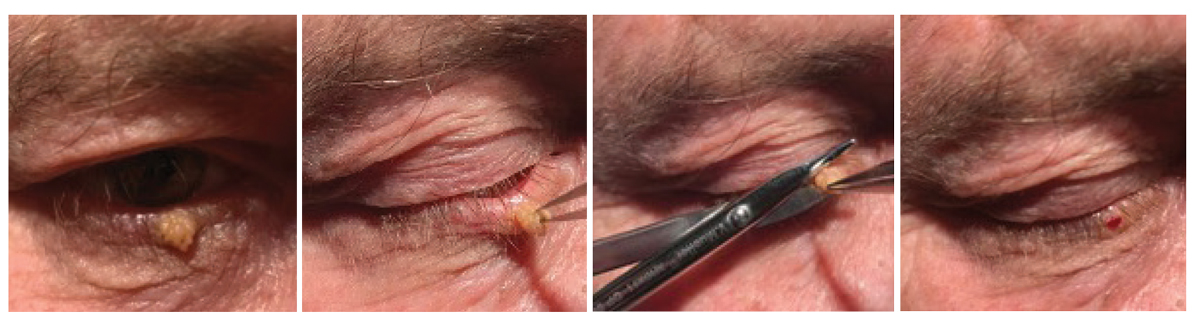

“The majority of lesions I find myself removing are stubborn, irritating skin tags,” says Dr. Collins. “These small papillomas typically make their home in the creases of the eyelids where most patients find it to be uncomfortable or irritating.” She also adds that lesion size and location can help you determine if a local anesthetic is necessary.

“I typically do not inject local anesthetic if the papilloma is small or very close to the lid margin,” Dr. Collins explains. “This is just personal preference due to the pain involved with the injection being the same, if not more, than what is endured with the removal alone.”

In cases where local anesthetic is warranted or preferred by the patient, it can be helpful to mark the lesion before injecting to ensure the original borders, according to Dr. Collins. “You will be inserting the needle laterally at 5-10 degrees with the bevel up and aspirate to ensure correct location,” she explains. Then, after injecting 0.5mL to 1mL of anesthetic, gently massage the area and wait five minutes for the medication to take effect.

“One stick is best—so inject a portion of the anesthetic (lidocaine, for instance) and, without pulling the needle out of the skin, back it up a bit, then push forward in another direction,” advises Dr. Bendure. “Do this a few times until you have infiltrated the entire area beneath the lesion and then remove the needle.”

How to Cope With Your New ScopeThe optometric profession is currently in the midst of a new wave of expanded scope of practice legislation, both proposed and enacted, with many bills aimed at bringing “hands-on” procedures like lesion removal and minor laser surgery to optometry. Others seek to plug the remaining holes in optometric pharmaceutical prescribing rights, notably in oral medication use. Most recently, Virginia passed legislation enabling its ODs to perform three types of laser surgery—YAG capsulotomy, laser peripheral iridotomy and selective laser trabeculoplasty—while similar efforts in Alabama were stymied by opposition. Though the fight for expanded scope of practice is far from over, ODs can use this growing momentum to enhance not only their own practices but also the profession and eye care at large. “I have witnessed optometry evolve from a material and retail-based profession to a healthcare service-based profession,” notes Dr. Castillo. “The transformation began in the 1970s when optometry started administering eye drops to screen for disease, and since then, the profession has become the largest provider of primary eyecare services in the nation. Today, we have nine states with statutory laser authority and almost 20 states with some level of surgical procedure authority. This progress is only going to continue,” he says. To help you better understand the new and emerging practice privileges, we are publishing a series of four articles that delve into the various categories of scope expansion, offering clinical best practices and discussing the logistics of adding each service. This first article highlights incisions and injections: where to start when integrating these procedures, what tools are needed and how to achieve great outcomes. The remaining three articles in this scope expansion series, which will appear across our next several issues, will include guides to laser surgery, glaucoma treatment and prescribing oral medications. If you practice in a state where you’re already able to offer these services to your patients, this series will provide you with a refresh on the basics of each procedure and give you advice on bettering your practice flow. If you practice in a region where expansion efforts are still underway, each of these four articles will offer information on what you should know and can do to help prepare you and your staff for when it comes time to incorporate these new and exciting services into your clinic. |

After creating a sterile environment and positioning the necessary equipment close by (a sterile betadine swab, sterile gloves and erythromycin ointment), Dr. Collins says she usually removes these lesions outside of the slit lamp using a headband magnifier. She finds that this method allows for a much larger range of motion while maintaining the same level of clarity.

Dr. Collins takes the following steps for the procedure of removing a lesion around the eye:

- Wash hands thoroughly and put on sterile gloves.

- The sterile betadine swab is applied to the lesion and the surrounding area—starting at the lesion and circling out.

- Once dried, take the tissue forceps (she uses the Adson brand) to pull the lesion away from the skin to get the best view of the base of the lesion. Then, use the Westcott tenotomy scissors to cut the lesion at its base.

- If a biopsy is warranted, place the specimen in the container, fill out the appropriate paperwork and send it to the practice’s local lab.

“Usually there is very minimal bleeding involved in these procedures, thus there is very little clean-up to the affected area,” says Dr. Collins. “Lastly, I apply erythromycin ointment to the affected area and prescribe the patient a 3.5g tube to continue to use BID until I see them back for their post-op, which is usually one week later.”

Lesion Removal: Best Practices to RememberFirst and foremost, it is important to have a clear understanding of the different types of “lumps and bumps” and the characteristics of skin lesions that imply benign, malignant or uncertain, notes Dr. Bendure. The standard of care in all 50 states dictates lesions with risk of malignancy be tentatively diagnosed as cancerous and biopsied, notes Dr. Castillo. Most states prohibit ODs from removing a cancerous growth; therefore, referral to an ophthalmic surgeon for excision and biopsy to rule out malignancy is necessary in those cases. Another key component is anatomy. While ODs have been taught this information, Dr. Bendure urges them to brush up on their knowledge before initiating these procedures in their clinic. “For instance, in the case of triamcinolone injection for a chalazion, you want to make sure you don’t cause a central retinal artery occlusion—that really is a possibility,” he says. There are anastomoses between the superficial vessels and the ophthalmic artery, he explains. “If you happen to inject directly into a vessel, you could easily overwhelm the pressure gradient, push the steroid suspension retrograde into the ophthalmic artery and cause blindness,” he adds. “So, you should always pull back on the plunger to check for a flash of blood and ensure you aren’t going to inject into a vessel.” Other best practices:

|

When removing lesions, it is important to consider how deep you need to go, according to Dr. Bendure. Is it a pedunculated squamous papilloma, for instance, which will likely be a simple snip? Or is it a sessile nevus, which would be better treated with radiosurgical excision to provide a better aesthetic appearance after healing?

Hidrocystoma, also known as a sudoriferous cyst, is another type of lesion Dr. Collins frequently sees in patients at her practice. These lesions can be easily lanced and drained in the office. In most cases, she uses a scalpel blade to open the cyst and then drains the fluid while holding gauze pads to the area to assist with clean-up.

“On some occasions, you will need to use the Westcott scissors to remove additional skin that could be present once the fluid is drained,” she said. “Lastly, you will apply erythromycin ointment to the affected area, prescribe it BID to the area and evaluate it at the post-op visit one week later.”

|

|

From left to right: Squamous papilloma pre-op; isolation of papilloma using forceps to expose the base; surgical scissors are used to snip the lesion at its base; immediately after lesion removal with snip excision. Note the minimal amount of blood seen in the last image. Click image to enlarge. |

For chalazion removal, Dr. Collins prefers to err on the side of caution and makes sure the patient has been using heat masks twice a day for at least three months before considering removal or intralesional injections.

“When determining intralesional injection (Kenalog) vs. incision and curettage, there are a few things you need to consider,” she notes. “The steroid injection is only about 75% to 90% effective with 25% of patients needing a second injection, whereas incision and curettage is typically over 90% effective.”

The Don’ts of Lesion RemovalKnowing what not to do is just as valuable as knowing what to do. Here are a few missteps to avoid:

|

Another consideration is skin color. If the patient has darker pigmented skin, Kenalog could cause lightening of the tissue; for that reason, it’s typically contraindicated in this patient population, says Dr. Collins.

Just like any procedure, performing intralesional injection begins by establishing a sterile environment—with properly sanitized or disposable tools—followed by application of the betadine to the affected area and then either external or internal injection. “If you administer an injection externally, this will require you to inject tangentially to the globe; internal injections will require a clamp to evert the lid to inject,” explains Dr. Collins. “You will be injecting 0.2-0.4cc of 10-20mg/mL, applying gentle pressure afterwards and advising the patient to use erythromycin ointment BID for one week.”

Incision and curettage require a clamp to evert the lid, a scalpel to create a vertical incision (about 2-3mm away from the lid margin) and involve a curette to remove the internal contents, she outlines. “Lastly, forceps/Wescott scissors will be used to remove the fibrotic capsule to ensure it does not return. Once again, apply gentle pressure and prescribe erythromycin ointment BID for one week.”

Although the procedures described above are among the most common, gaining incision and injection privileges opens up broad new vistas that require the OD to recognize their capabilities—and their limitations. Be sure to have a protocol in place for appropriate referral of cases beyond your wheelhouse, as well as time in your schedule to continually work on building your skills and educating yourself on safety and best practices.

Prepping Your Clinic For Incisions and InjectionsSuccessful incorporation of new procedures depends, in part, on having the necessary tools at your disposal. For instance, it is important to have specific procedure consent forms as well as pathology vials and forms, according to Dr. Collins. To offer lesion removal and injections, the initial set-up shouldn’t break the bank. Tools to have on hand include:

Depending on the types of lesions ODs at your practice are planning to remove, a radiosurgical unit may be a beneficial addition to your clinic. Another consideration is whether to invest in reusable or disposable tools. Dr. Bendure brings up the point that advantages can be seen with either option as you compare initial costs vs. the time required to clean and sanitize surgical instruments. Ultimately, he notes, it’s up to the optometrist to determine what works best for their individual practice and the patients they care for. |

Looking Ahead

As the current wave of scope expansion continues to gain momentum across the country, ODs are in the perfect position to take advantage of this progress for the benefit of their patients, practices and profession. By practicing to the fullest extent of their scope, optometrists are able to provide their patients with the highest level of care possible.

“As primary eye care providers we have the responsibility to give our patients the best access to timely, comprehensive care,” notes Dr. Burress. “And so, if it is within our scope to provide additional services that can save our patients time and money, we need to. This is especially important in rural areas that may have limited facilities close by. The more we can do in-office to meet our patients’ needs and improve the quality and convenience of their care, the better.”

Optometrists who currently don’t have the ability to perform these procedures in their state have a key role to play in changing that. Get involved with your professional organizations and help raise awareness among the community and legislators. “Building a relationship with your state representatives is crucial,” says Dr. Castillo. “Become a resource for legislators and participate in the grassroots efforts in your state.” In order for the voice of optometry to overtake that of the opposition, those who work directly in the field must be active advocates for expansion laws.

For those ODs whose scope of practice has expanded and are considering adding a new service, Dr. Collins encourages them to take the leap. “Our profession has fought to expand our scope to meet the same level as our education and training, so get out there and capitalize on the opportunities given to us,” she says. “By integrating this into your practice, you will be providing top-tier optometric care and will be able to continue giving your patients the level of care they deserve.”