Taking the Lead on GlaucomaJuly's issue is our 28th annual glaucoma report, where we explore the latest in treatments, technology, MIGS and diagnostic techniques to manage your patients with this aggressive disease. |

As a lifelong, vision-threatening disease requiring frequent monitoring and treatment, glaucoma is one of the most common conditions optometrists handle on a daily basis. Most of the United States relies on ODs as their primary eye care providers; thankfully, recent legislation has made it possible for every OD across the country to offer glaucoma patients care close to home from a clinician they trust. In addition, one in five states can now perform selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), which is moving towards becoming a first-line treatment for glaucoma. Now more than ever, as practice rights for optometrists continue to increase, it’s time to take the reins on glaucoma management at your practice.

No matter what level of glaucoma care you currently offer or which services are authorized in your state, it’s critical to the health of your patients and your practice to stay informed and be prepared to implement the evolving techniques to manage the condition. Below, we provide ODs with guidance on how to expand on existing glaucoma services while embracing newer opportunities such as SLT to maximize the level of care offered to patients.

This article is the third in our scope expansion series, following one on incisions and injections (May) and another on lasers (June), all with the goal of helping you navigate these exciting new roles and responsibilities for ODs.

The Evolving Role of ODs in Glaucoma

Unlike the other procedures and services previously discussed in this series, the legislative battles regarding glaucoma management have—for the most part—been won. As of 2021, all optometrists in the United States can treat the condition topically, but the net wave is heating up, as 10 states now allow ODs to perform at least one type of laser procedure.

|

|

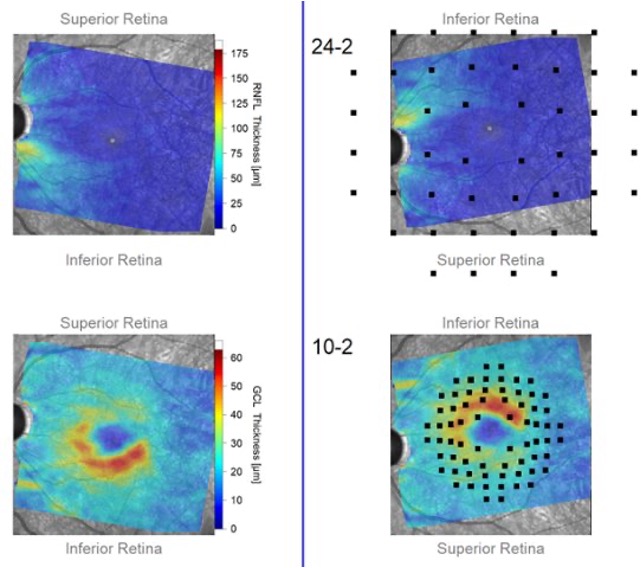

Images show macular structural data with superimposed visual field loci taken from a portion of a Hood Report, which is one tool that can aid in glaucoma diagnosis. All photos in this feature courtesy of Andrew Rixon, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

In January 2021, Massachusetts became the last state to give optometrists the authority to treat patients with glaucoma. Under the new legislation, comparable to that in many other states, ODs in Massachusetts can now prescribe topical and oral therapeutics including schedule III, IV, V and VI drugs for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of glaucoma. They can also prescribe all necessary eye medications including oral anti-infectives.

Fast-forward a few months to June 2021, when legislation in Texas granted optometrists the authority to independently manage glaucoma patients—eliminating the previous requirement of comanagement with an ophthalmologist, which is the case in a growing portion of the country. In addition, the Texas scope bill allows optometrists in the state to prescribe any oral medication used to treat eye conditions.

Most recently, Colorado claimed the title of the 10th state to allow optometrists to use lasers when its sunset bill was signed by Governor Jared Polis early last month. The as-taught law means that, in addition to enjoying several other new practice rights that align with current training and education, ODs in Colorado can now offer their glaucoma patients more treatment options aside from the standard eye drop, one example being SLT. (You can read more about Colorado’s recent scope expansion here.)

SLT is becoming accepted as a first-line treatment for patients with open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension since the release of data from the LiGHT trial, which reported its effectiveness over topical therapy. The study found that 74% of patients treated with SLT required no drops to maintain their target intraocular pressure three years after the procedure. It also found that patients who received SLT were within their target pressure more often than those treated with eye drops (93% vs. 91%).

With the increasing availability of SLT and research supporting its potential, ODs are in the perfect position to take the lead and manage this progressive, chronic condition and provide a very high level of care to their patients.

Scope Expansion SeriesRead the other articles featured in this series:

|

Despite these recent significant gains in scope expansion, there remains a need for more OD involvement in glaucoma. The number of patients with glaucoma—and those with potential risk for blindness due to the disease—is projected to increase from three million in 2020 to 6.3 million by 2050. According to Andrew Rixon, OD, an attending optometrist and the residency coordinator at the Memphis VA Medical Center, “Glaucoma is an optometry problem, and we have a necessity to help combat this disease,” he says. “A majority of cases are still underdiagnosed, and as front-line providers we are often the entry point to patient healthcare. It’s a fundamental part of our job as primary eyecare providers. Our job is to maximize vision and a critical component of maximizing vision comes through prevention of vision loss.”

Now let’s take a closer look at how to integrate glaucoma management into clinical practice and lay the foundation to successfully take on a larger role in caring for this patient population.

Tools You’ll Need

When incorporating glaucoma care into practice, optometric education has prepared ODs to manage this multifaceted disease, according to Jackie Burress, OD, who practices in the Eastern Oklahoma VA Healthcare System, who also notes that there are a number of continuing education resources readily available to help optometrists refresh their knowledge on or learn about new tools and medications. As always, you should check with your state board to ensure you are following all the necessary protocols before implementing new services into your practice.

|

|

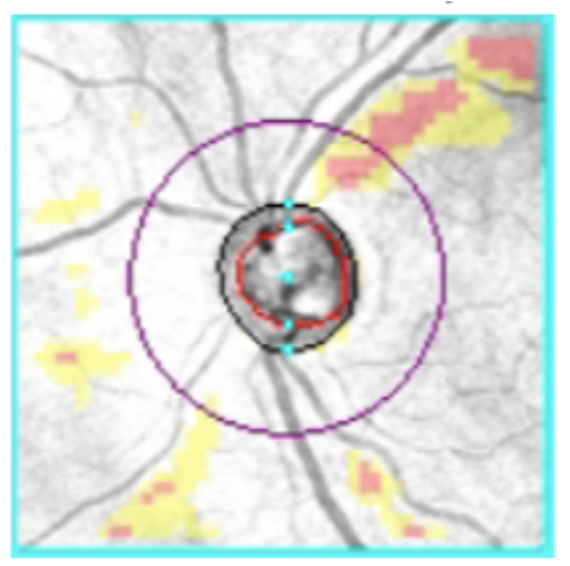

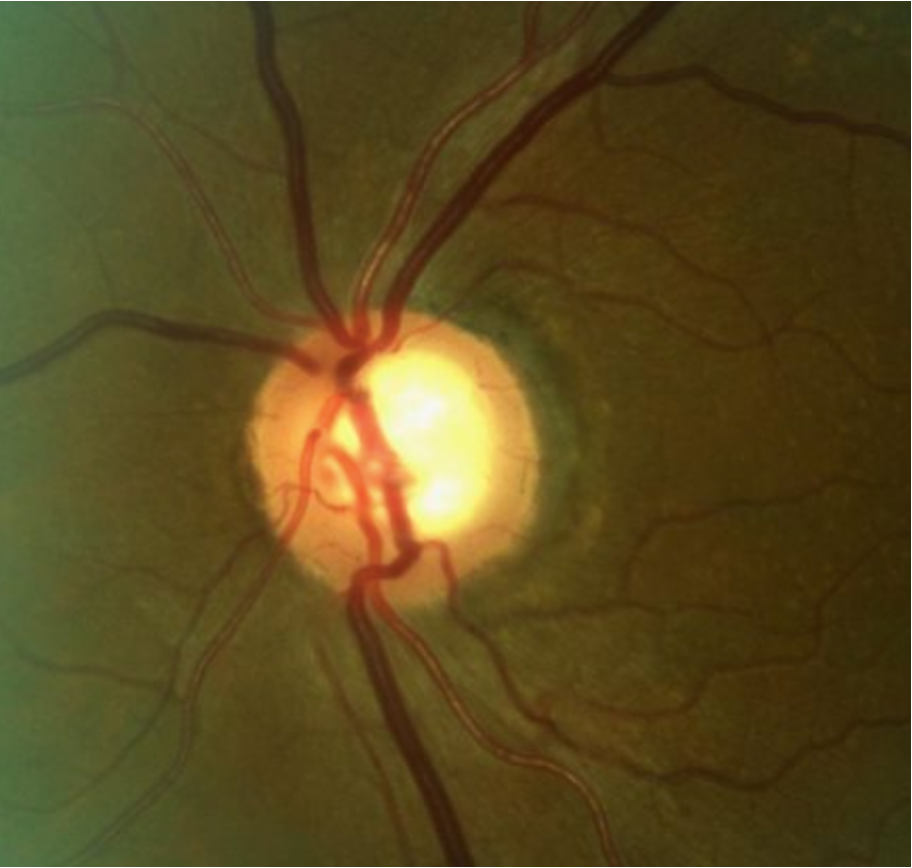

Structural changes in the optic nerve rim can signify glaucomatous progression. Click image to enlarge. |

A core component of effective glaucoma management is having the right tools at your disposal. “Practitioners need high-quality instruments to determine the risk of glaucoma, classify the type and stage and identify subtle progression,” says Shaleen Ragha, OD, who practices at The Eye Center at the Southern College of Optometry. These instruments include spectral-domain or swept-source OCT with high resolution, accurate and repeatable tracking, minimal inter-visit variability and a relevant patient database. “The optic nerve rim, retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), circumpapillary RNFL and macular ganglion cell layer thicknesses are key indicators for diagnosis and progression. High-quality imaging is crucial to delineate correct layer segmentation and repeatability,” she says.

When purchasing an OCT, Dr. Ragha urges ODs to take advantage of the company’s customer service team to better understand the device’s acquisition abilities, sources for error and manipulation and extraction of data.

Dr. Burress acknowledges that an OCT is a significant expense; however, she notes that if a practice is able to afford the cost, the device will provide lots of valuable information about the optic nerve and ganglion cells. “With OCT, we are now able to monitor for minor changes that would have been undetectable prior to this technology,” she says.

If an OCT is out of an optometrist’s price range, Dr. Burress recommends seeking creative solutions, such as mobile technology companies that allow you to rent the OCT for a day or partnering with a fellow OD in the area who has an OCT in-house. “Oftentimes, you can refer for the test, and then they will send your patient back to you for management.”

It is also important not to overlook the importance of gonioscopy, according to Dr. Burress. “A gonio lens is cost-effective and allows you to learn valuable information about your patient,” she points out. “You can examine the angle to differentiate between open-angle and closed-angle glaucomas and assess for signs of damage from trauma, including angle recession and synechia. Gonioscopy also allows us to determine the best candidates for SLT.”

Once your state’s law allows ODs to perform SLT, that will be another investment to consider. As noted in last month’s article on lasers from this scope expansion series, ODs can choose to purchase a stand-alone or a combination laser from various companies. Most new YAG/SLT combination lasers are cheaper than an OCT with a price tag of $40,000 or less. Refurbished equipment that comes with a warranty is also a great option for those in search of a more wallet-friendly solution.

Steven G. Zegar, OD, practices in Slidell, LA, which passed its optometric laser bill in 2014. He has since performed hundreds of ophthalmic procedures (primarily capsulotomies, but some SLT as well) and witnessed the benefits it’s had on his practice and his patients. Dr. Zegar urges optometrists who are hesitant to invest in a laser to consider the various alternatives to be able to offer SLT and other laser services to your patients. “You can ask to use another local optometrist’s laser, as well as ask if you can shadow them during the procedure,” he says. In addition, Dr. Zegar adds, “There are also services in some locations that can rent you a laser. That’s what we do at our practice; someone from the equipment company brings the laser to my office once a month on a Wednesday morning for two hours.” This option allows you to schedule patients’ laser procedures during the time window you choose without having to front a high cost.

With SLT playing an increasingly prominent role in glaucoma care, you may want to consider adding this instrument to your clinic if you have the means. The more treatment options you can offer your patients—especially when it’s something other than a drop—the more satisfied they will be with your care.

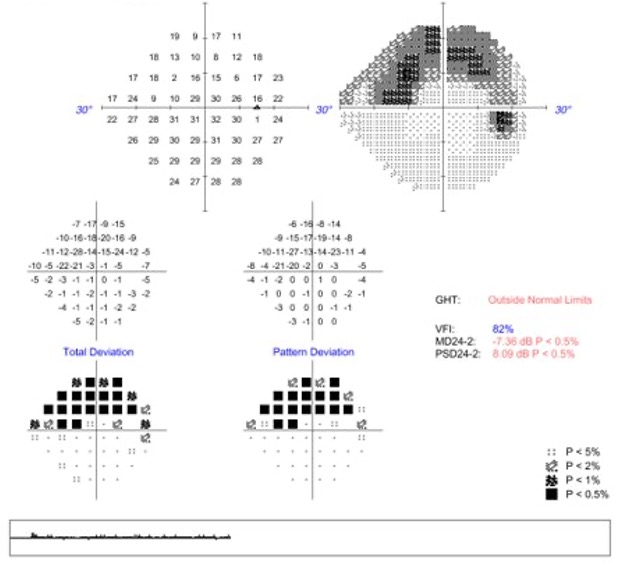

Another important tool is an automated visual field that performs threshold testing to evaluate function in correlation to structure, as seen on fundoscopy and OCT, Dr. Ragha suggests. She also notes that “a trained technician is helpful to ensure good instruction to the patient and communication of test observations to the doctor. Since it is a subjective test, reliability should be considered in interpretation.”

There are a number of other devices that aid in the diagnosis of and risk assessment of glaucoma. Goldmann applanation tonometry is the current gold standard for measuring intraocular pressure (IOP), according to Dr. Ragha. “The Goldmann tip comes with most slit-lamp instruments and appropriate sterilization is recommended,” she explains. “As for ophthalmic diagnostic pharmaceuticals, Fluress (fluorescein benoxinate) or a topical anesthetic with a fluorescein strip can be used.”

Corneal pachymetry is also helpful to determine the risk of progression and also under- or over-estimation of Goldmann IOP readings, explains Dr. Ragha. She notes that an OCT with anterior segment capability or an ultrasound pachymeter can be used.

To document optic nerve and RNFL appearance at baseline, Dr. Ragha finds fundus photography to be helpful. This can be repeated if any changes are noted. “Color imaging, specifically using blue- or red-free filters, can highlight RNFL defects,” she says.

|

|

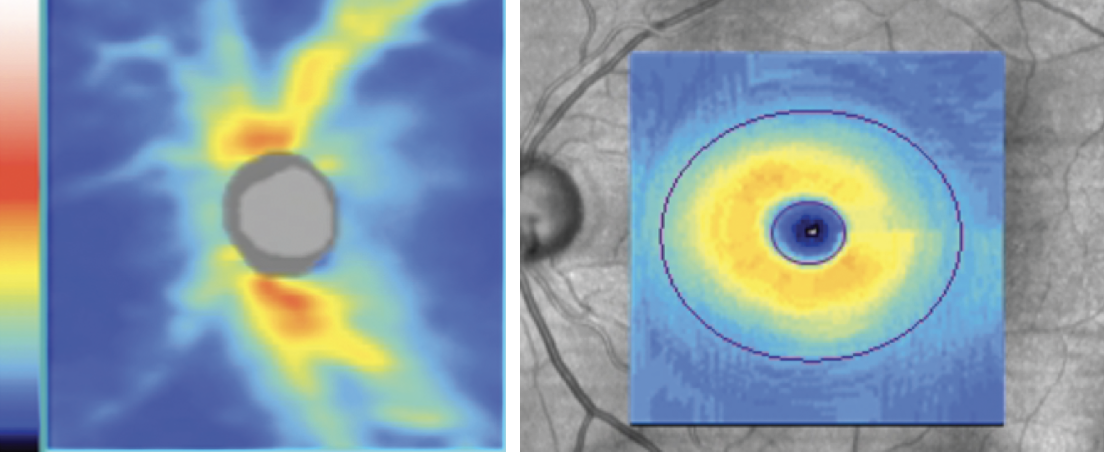

It’s important to analyze all tissue that can be affected by glaucoma, which includes both the optic nerve head and the macula. Click image to enlarge. |

Preparing Staff

Staff education is also a key component to successfully incorporating glaucoma care into your practice. This is a multitiered process, according to Dr. Rixon, and begins with an understanding of the comprehensive care provided by the doctor as well as ongoing education to ensure patients receive the highest quality of care.

“Administrative staff is then able to promote to the patients what services the doctor provides and what skills and time are involved in their respective visits,” he says. “Secondly, clinical staff will need to become proficient in performing the new technologies that are brought into the practice and be able to explain why each technology is being used.” For example, if or when your practice introduces SLT, ensure the entire staff is prepared to answer questions about the newer therapeutic option that most patients will be unfamiliar with.

Oftentimes, he notes, clinical staff will be responsible for educating patients on medication instillation and drop schedules as well as communicating with patients during phone calls and telehealth appointments. Therefore, it is important that they receive the necessary training and education to support coherent glaucoma management within the practice.

Detecting and Diagnosing

As with any condition, enacting a care plan begins with an appropriate diagnosis. “Glaucoma is a chronic, progressive optic neuropathy that involves loss of both neural and connective tissue (lamina cribrosa),” Dr. Rixon notes. “Although it is often conflated with glaucoma, elevated IOP is nowhere in any consensus definition of glaucoma; rather, it is a risk factor.”

IOP and the OD: Advice on Setting a Target PressureA key aspect of glaucoma management is IOP. Guidelines suggest that you should set a target IOP that is intended to be the level at which you prospectively hope the patients’ disease will be slowed and their vision preserved, explains Dr. Rixon. While there is no consensus on how to set a target IOP, generally speaking, the worse the disease is, the lower the goal IOP should be. “Setting a target IOP is a part of the overall risk management process, but it is not the ultimate determinant of successful or failed treatment,” he says. “It’s dynamic and can be intensified or loosened according to how the disease behaves. The ultimate determinant of success or failure is in slowing the rate of disease progression, which is determined most readily by watching for structural and functional progression.” Dr. Rixon urges ODs to always keep in mind that IOP is a highly dynamic parameter. “Our ability to catch the peaks and valleys of eye pressure over 24/7/365 is limited, especially as we typically only capture an extremely small snapshot of IOP when we get a single reading during our visits,” he notes. That’s why it’s important to caution your patients not to fixate on the IOP captured during follow-ups. Patience is key. Determining trends and understanding the rate of progression doesn’t happen overnight. Dr. Rixon suggests labeling follow-ups as glaucoma progression evaluations instead of blanket IOP checks. This reinforces—for both you and your patient—what you’re trying to combat. “You have to take the 30,000-foot view of these patients and consider more than just the snapshot IOP that day. A big issue I see in the various clinics I have worked at is the hair-trigger reaction to not meeting a target pressure,” he says. “The target IOP is an educated guess and is not set in stone. The highest level of IOP at which the patient is still susceptible to damage may take time to figure out.” |

Therefore, the most important step involved in designating a patient as a glaucoma suspect or as having glaucomatous optic neuropathy is conducting a detailed, stereoscopic evaluation of the optic nerve head.

While there are myriad risk factors associated with the development of glaucoma, ODs have to anchor the work on their optic nerve head evaluation to begin the diagnostic process and build a baseline of structural and functional information to work from, he advises.

“Thinning of superior-temporal or inferior-temporal rim tissue is a sign of glaucomatous damage, whereas a large cup-to-disc ratio may be normal for a large-size disc,” adds Dr. Ragha. “IOP is an important risk factor; however, remember that low-pressure glaucoma can still exist, as well as ocular hypertension, in cases where there are no signs of glaucoma.” She emphasizes that this is why a full workup that includes pachymetry, gonioscopy, OCT and visual fields is necessary.

|

|

Loss of prelaminar neural tissue in a patient with myopic glaucoma. Click image to enlarge. |

It is important to note that IOP also has diurnal variation, so OCT and visual field evaluation should have more emphasis when deciding on the course of management, according to Dr. Ragha. Instrumentation errors, artifacts and concurrent disease should be considered when interpreting OCT and visual fields.

“From my experience in teaching, the most common mistake is evaluating summary reports and skipping review of the actual scans or plots,” Dr. Ragha notes. “For any serial testing, new scans and fields should be compared to the baseline, which may be the last time progression was noted or a treatment change was made.”

Classifying the type of glaucoma you are dealing with is also critically important. Do not assume every case is one of primary open-angle glaucoma, Dr. Rixon warns. Gonioscopy is underused in optometry and ophthalmology; however, he notes, this tool is key to accurate classification.

Starting—and Keeping—Patients on Treatment

Once a glaucoma diagnosis has been made, a patient-centric approach to care with shared decision-making is required, according to Dr. Rixon, who says that this begins with a baseline level of knowledge of the disease. Since each patient has a different level of healthcare literacy, the OD must first try to understand what the patient does and does not know before education begins.

|

|

Superior arcuate defect in a patient with moderate glaucoma. Click image to enlarge. |

“Personally, I believe setting expectations on the front end about how dynamic the patient’s individualized care can be is critical,” he says. “Patients need to understand that the number of visits they will need initially and throughout the course of the disease will depend entirely on how their disease behaves and that as a team, we will chart out a custom course together.”

Manner and urgency of treatment depend on multiple factors, including disease stage at diagnosis, quality of life, risk tolerance, life expectancy, ability to administer medications, side effects of treatment and consideration of ocular comorbidities such as surface disease.

For ODs who are able to perform SLT, Dr. Burress recommends considering this as a first-line treatment. “This procedure is becoming more common in practice. It is also great to recommend in patients who have a history of poor compliance with traditional glaucoma medications.” Using an SLT laser, treatments are generally applied 360 degrees to the trabecular meshwork using adjacent, non-overlapping spots (approximately 100). The goal is to see tiny “champagne bubbles” in the anterior chamber during the procedure.

It’s important to note that SLT isn’t the best choice for every glaucoma patient: it’s contraindicated for neovascular glaucoma, and for those with heavily pigmented trabecular meshwork, energy settings of the laser may need to be decreased. (Interested in adding SLT to your optometric toolbox? Check out the previous article in this series, “Adding Lasers to Your Practice,” featured in our June issue, for step-by-step advice. Click here to read it online.)

Hesitant to Manage Glaucoma? Here’s AdviceIntegrating a new service into clinical practice is not a simple task, and while it is natural to feel hesitant, your optometric skills will serve you well in this challenge. Adding glaucoma care to your repertoire not only benefits your patients but also enhances own practice and professional growth. Drs. Burress and Rixon offer some advice and inspiration below.

|

When opting to start a patient on topical medications, Dr. Rixon emphasizes the importance of assuming patients are not compliant with drop installation, as that is the more likely scenario. Instructing the individual on how to properly instill meds and having them demonstrate successful instillation prior to leaving the office will ensure that lack of knowledge on how to administer the medication is one less deterrent to adherence. This task, he notes, can be delegated to clinical staff and reinforced to patients with educational handouts and videos.

“The simpler, the better,” advises Dr. Rixon. “If possible, start with a once-daily medication for ease of instillation and be flexible with when it is instilled. PGAs have been shown to blunt the diurnal/nocturnal IOP curve up to 84 hours post-instillation. Flexibility with the drop schedule isn’t an issue, as long as it doesn’t reduce treatment effectiveness.” One idea to promote adherence is to have patients instill their drops at the same time as they take their other medications, if they are prescribed any.

It is also important to take your patient’s insurance and financial information into consideration, suggests Dr. Burress. If the drop is too costly, compliance will be affected. Consider opting for glaucoma drops with a lower copay that provide good IOP management, such as timolol. However, when prescribing this drug, Dr. Burress says you must “be sure the patient has a resting pulse rate at 60 beats per minute or above so that bradycardia does not occur. Also, check to see if the patient is on a systemic beta-blocker, as this can lower the efficacy of timolol.”

Continuous Monitoring of Disease Progression

Frequent in-person follow-up is a key component of any chronic condition. After a diagnosis, Dr. Rixon prefers to bring patients back for a six-week evaluation, which is used to assess any side effects of treatment, unforeseen burden of treatment, adherence issues and to answer any questions that the glaucoma patient may have. The goal is to establish sufficient baseline information to detect the rate at which a patient is progressing.

The World Glaucoma Association recommends two reliable baseline visual fields within the first six months of treatment and at least two additional fields within the following 18 months for mild to moderate disease. Six total visual fields are recommended in the first two years in patients at high risk of visual disability.

OCT scans of both the macula and optic nerve are crucial when assessing the structure of the neural and connective tissues affected by glaucoma. Careful assessment of the structure will help guide visual field strategies and provide a more comprehensive understanding of a patient’s disease.

|

|

Superior temporal rim erosion and corresponding RNFL thinning in a patient with early POAG. Click image to enlarge. |

“The most studied and repeatable parameter on OCT to gauge progression is the average or global RNFL. Generally, a baseline OCT and an additional OCT at six and 12 months from diagnosis are beneficial to address machine test-retest variability and rule out your patient being a fast progressor,” Dr. Rixon says, while noting that testing regimens should be customized to the individual.

When considering glaucoma management, Dr. Rixon notes that while early and aggressive intervention is desirable, it has to be done judiciously. “Immediately reacting to a few in-office post-treatment IOP readings often results in unnecessary escalation and complicates matters for both the patient and practitioners,” he says. “If the total picture shows that the patient is at high risk for progression or is progressing at the current level of treatment, then additional intervention is necessary.” Dr. Rixon emphasizes that providers of glaucoma care need to “manage the disease, not the IOP.”

Common Challenges and Pitfalls

While ODs are equipped with the skills and knowledge to effectively manage glaucoma patients, implementing this service into clinical practice does not come without its difficulties. “Don’t assume that there won’t be any bumps in the road,” urges Dr. Rixon. “There is a learning curve to integrating any new service, and it’s important to stay the course no matter how frustrating and humbling the growth process can be.”

Glaucoma management is a long-term commitment, and you can’t assume that “if you build it, they will come,” he says. “You need to constantly avail patients of the services you provide. This goes back to educating your patients and re-emphasizing that you are their primary eyecare provider.”

Integrating new technology is also an ongoing process. As a provider, you are essentially learning a new language in a world that is constantly evolving, explains Dr. Rixon. “It is a time-consuming task to keep up with all the innovation in technology. Although product manuals are great in teaching how to acquire good information, they are not universally good at teaching how to interpret and apply that information,” he points out. “There is a time commitment that may not be expected on the front end.”

Dr. Burress emphasizes that ODs should avoid thinking that implementing this service will show them down in the clinic. “Since IOP and nerve assessment is something done at every routine exam, you are already screening for glaucoma on a daily basis,” she says. She adds that it is important to remember that multiple visits may be necessary to gather the information needed to diagnose glaucoma.

Since no noticeable symptoms are associated with this chronic disease until advanced stages, patients often have a poor understanding of the condition, notes Dr. Ragha, which can be a challenge for the OD. “To further complicate this misconception, treatment at that point will not restore vision loss,” she says. “Spending time explaining the condition and treatment as well as briefly showing test results at each visit can help patients understand their glaucoma.”

Medication adherence is a known issue with glaucoma patients, according to Dr. Rixon, who notes that studies show as few as 10% of patients make it a year without a major gap in treatment.

“Adherence patterns established in the first year are often indicative of future patterns, so early and consistent education about the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of glaucoma care is key,” he says. “Open-ended communication and employing an ask-tell-ask method has been shown to improve detection of medication non-adherence and consequently improve adherence.”

Providing Comprehensive Care

When embracing glaucoma management, ODs are the clinicians who can and should take the lead, and fortunately, the evolving legal landscape agrees.

“We want to offer the best care for our patients with the greatest outcome possible,” Dr. Ragha says. “Access to care is an issue for many people, especially the elderly. Offering glaucoma care close to home allows them better access to treatment and the patient will be more willing to follow-up.”

Dr. Zegar recommends choosing to partner up with ophthalmologists and other physicians who support the expansion of optometry’s scope of practice. In addition to networking with local specialists such as endocrinologists and dermatologists who often need to refer patients to eye doctors, it’s also beneficial to invite them to your practice and show them which procedures you perform and which equipment you use. “I’m getting anywhere from eight to 12 weekly referrals from internal medicine,” says Dr. Zegar. “It takes work and effort to form and maintain these connections, but it really helps your practice grow, especially once you offer the more advanced procedures.”

And if you’re further along in your career than others, don’t write off glaucoma—including laser procedures—as something for the next generation. Dr. Zegar was 71 years old when Louisiana passed its laser law. Today, at age 79, he still sees patients 4.5 days a week. “I feel any of my peers who do not take advantage of these highly expanded modes of practice are depriving themselves of intellectual challenge and not serving their respective communities to the fullest extent,” he says. “Adding lasers brightened as well as extended my view of optometric practice.”

When optometrists work at the top of their expertise, everyone benefits. “Most of us chose this field because we want to take care of people’s vision and ocular health,” says Dr. Ragha. “Insurance reimbursement and cost of equipment and staff play a role in the hesitancy of managing specific conditions. However, the knowledge you need to manage glaucoma is at your fingertips, and your patients benefit from the wide scope of care.”

Next month: Part 4 of this series will delve into the use of oral medications.

1. Boyer DS, Schmidt-Erfurth U, van Lookeren Campagne M, et al. The pathophysiology of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration and the complement pathway as a therapeutic target. Retina. 2017;37(5):819-35. 2. Armento A, Ueffing, M, Clark, SJ. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(10):4487-505. 3. Sepp T, Khan JC, Thurlby DA, et al. Complement factor H variant Y402H is a major risk determinant for geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularization in smokers and nonsmokers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(2):536-40. 4. Scholl HP, Fleckenstein M, Fritsche LG, et al. CFH, C3 and ARMS2 are significant risk loci for susceptibility but not for disease progression of geographic atrophy due to AMD. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7418. 5. Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(20):7227-32. 6. Apellis announces top-line results from phase 3 DERBY and OAKS studies in geographic atrophy (GA) and plans to submit NDA to FDA in the first half of 2022. https://investors.apellis.com/news-releases/news-release-details/apellis-announces-top-line-results-phase-3-derby-and-oaks. September 9, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. 7. Apellis announces pegcetacoplan showed continuous and clinically meaningful effects at month 18 in phase 3 DERBY and OAKS studies for geographic atrophy (GA) [press release]. https://investors.apellis.com/news-releases/news-release-details/apellis-announces-pegcetacoplan-showed-continuous-and-clinically. March 16, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. 8. Jaffe GJ, Westby K, Csaky KG, et al. C5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized pivotal phase 2/3 trial. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(4):576-86. 9. Iveric Bio announces positive Zimura 18 month data supporting the 12 month efficacy findings: continuous positive treatment effect with favorable safety profile in geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration in a phase 3 trial [press release]. https://investors.ivericbio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/iveric-bio-announces-positive-zimura-18-month-data-supporting-12. June 15, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. 10. A phase 3 safety and efficacy study of intravitreal administration of Zimura (Complement 5 Inhibitor). ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 22, 2022. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04435366. 11. NGM Bio. Our Pipeline. www.ngmbio.com/pipeline. Accessed March 22, 2022. 12. A study investigating the efficacy and safety of intravitreal injections of ANX007 in patients with geographic atrophy (ARCHER). ClinicalTrials.gov. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04656561. Accessed March 22, 2022. 13. Clinical study to evaluate treatment with ORACEA for Geographic Atrophy (TOGA). ClinicalTrials.gov. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01782989. Accessed March 22, 2022. 14. A phase 3 study of ALK-001 in geographic atrophy (SAGA). ClinicalTrials.gov. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03845582. Accessed March 22, 2022. 15. Alkeus Pharmaceuticals ALK-001: once-a-day oral, investigation therapy to prevent blindness. www.alkeuspharma.com/pipeline.html#alk-001. Accessed March 22, 2022. 16. Phase 2 tolerability and effects of ALK-001 on stargardt disease (TEASE). ClinicalTrials.gov. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02402660. Accessed March 22, 2022. 17. Kuppermann BD, Patel SS, Boyer DS, et al. Phase 2 study of the safety and efficacy of brimonidine drug delivery system (Brimo DDS) generation 1 in patients with geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2021;41(1):144-55. 18. Klein R, Meuer SM, Knudtson MD, Klein BE. The epidemiology of progression of pure geographic atrophy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Nov;146(5):692-9. 19. Zhang QY, Tie LJ, Wu SS, et al. Overweight, obesity and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(3):1276-83. 20. Kuan V, Warwick A, Hingorani A, et al. Association of smoking, alcohol consumption, blood pressure, body mass index and glycemic risk factors with age-related macular degeneration: a mendelian randomization study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(12):1299-306. 21. Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamin C and E, beta carotene and zinc for AMD and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417-36. 22. Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309(19):2005-15. 23. de Koning-Backus APM, Buitendijk GHS, Kiefte-de Jong JC, et al. Intake of vegetables, fruit and fish is beneficial for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;198:70-9. 24. Merle BMJ, Colijn JM, Cougnard-Grégoire A, et al. EYE-RISK Consortium. Mediterranean diet and incidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration: The EYE-RISK Consortium. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(3):381-90. 25. Keenan TD, Agrón E, Mares J, et al. Adherence to the mediterranean diet and progression to late age-related macular degeneration in the age-related eye disease studies 1 and 2. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(11):1515-28. 26. Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Sahel JA, Danis R, et al. Natural history of geographic atrophy progression secondary to age-related macular degeneration (Geographic Atrophy Progression Study). Ophthalmology. 2016;123(2):361-8. 27. Fleckenstein M, Mitchell P, Freund KB, et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369-90. 28. Sunness JS, Margalit E, Srikumaran D, et al. The long-term natural history of geographic atrophy from age-related macular degeneration: enlargement of atrophy and implications for interventional clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):271-7. 29. Holz FG, Bindewald-Wittich A, Fleckenstein M, et al; Progression of geographic atrophy and impact of fundus autofluorescence patterns in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(3):463-72. 30. Yehoshua Z, Wang F, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. Natural history of drusen morphology in age-related macular degeneration using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2434-41. 31. Schlanitz FG, Baumann B, Kundi M et al. Drusen volume development over time and its relevance to the course of age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(2):198-203. 32. Sadda SR, Guymer R, Holz FG, et al. Consensus definition for atrophy associated with age-related macular degeneration on OCT: classification of atrophy report 3. Ophthalmology. 2017;125(4):537-48. 33. Jaffe GJ, Chakravarthy U, Freund KB, et al. Imaging features associated with progression to geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: classification of atrophy meeting report 5. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(9):855-67. 34. Christenbury JG, Folgar FA, O’Connell RV, et al. Progression of intermediate age-related macular degeneration with proliferation and inner retinal migration of hyperreflective foci. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(5):1038-45. 35. Zweifel SA, Spaide RF, Curcio CA, et al. Reticular pseudodrusen are subretinal drusenoid deposits. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(2):303-12.e1. 36. Finger RP, Wu Z, Luu CD, et al. Reticular pseudodrusen: a risk factor for geographic atrophy in fellow eyes of individuals with unilateral choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(6):1252-6. 37. Joachim N, Mitchell P, Rochtchina E, et al. Incidence and progression of reticular drusen in age-related macular degeneration: findings from an older Australian cohort. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):917-25. 38. Finger RP, Chong E, McGuinness MB, et al. Reticular pseudodrusen and their association with age-related macular degeneration: the Melbourne collaborative cohort study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(3):599-608. 39. Shi Y, Yang J, Feuer W, et al. Persistent hypertransmission defects on en face OCT imaging as a stand-alone precursor for the future formation of geographic atrophy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(12):1214-25. 40. Wu Z, Luu CD, Ayton LN, et al. Optical coherence tomography-defined changes preceding the development of drusen-associated atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(12):2415-22. 41. Wu Z, Luu CD, Hodgson LAB, et al. Prospective longitudinal evaluation of nascent geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(6):568-75. 42. Guymer RH, Rosenfeld PJ, Curcio CA, et al. Incomplete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: classification of atrophy meeting report 4. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(3):394-409. |