You have an old friend that visits your office every month. This friend comes to provide support, suggest advice, impart the latest news, provoke thought and perhaps share a laugh or two. This friend has shown up for many years now, and maybe in your busy day, you take your friend for granted.

Thats OK. Your old pal is always there for you, always at the ready when necessary, always at your elbow to nudge you along.

This month, your friendly visitor celebrates a big birthday. This month, your old pal Review of Optometry is 115 years old.

|

| Frederick Boger founded the magazine in 1891. |

Take a walk down memory lane to read about how this magazine has reflected the practice of optometry, has constantly encouraged the profession and has always championed the doctor of optometry. Looking back, you may be amazed to read how the problems you face today are similar to those faced by optometrists in the past.

At First Sight

Like the profession itself, Review of Optometry had humble beginnings. In the late 1800s, glasses were often fitted in jewelers shops. An optometrist was called an optician, and so was the magazine. When editor and founder Frederick Boger published the first issue in New York in January 1891, he named his magazine The Optician.

Mr. Boger recognized the need for education within the emerging but unorganized profession. At that time, training for many opticians consisted of a two-week course in refraction offered by optical equipment companies. Some opticians were self-taught through textbooks or correspondence courses. There were no professional journals or continuing education meetings.

|

Whats in a Name? Review in Review

1891. The Optician is first published to meet the needs of refracting opticians. 1895. The Optical Journal, after a short hiatus from its earlier incarnation, is introduced. 1910. The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry becomes a consolidated publication when the journal absorbs a three-year old publication The Optical Review. 1977. Review of Optometry, after years of reducing the name The Optical Journal in its logo, finally omits it altogether to emphasize the optometrists role as a health professional. |

But, providing practical hands-on information was only half the mission of Mr. Bogers magazine. He also used it as a soapbox to rally the profession and move it forward. In his March 1895 editorial in the re-named Optical Journal, Mr. Boger sounded the call for what would eventually become the American Optometric Association:

Now for a National Association or an American Association of Opticians! There has been no combined effort thus far to effect such an organization, but we propose now to do whatever we can to bring about such a thing. [A]n American Association, covering the whole country, is what is needed, and the men to run it should step forward and organize.

|

The Picture of Optometry

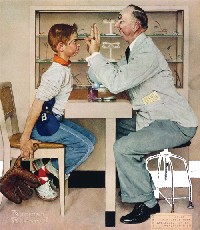

You probably had (or still have) this famous Norman Rockwell poster hanging on your office wall. (It was on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1956.) Indeed, many Americansand optometristsstill have this painting in their mind when they picture the optometric profession: the kindly old gentleman in his white smock.

But this picture will soon need an update. Tomorrows typical optometrist will be female, not male. Indeed, 60% of the students currently enrolled in optometry schools are women. Thats a big leap from 1950 (a few years before this picture was painted), when only 1.1% of optometry students were women, according to an estimate by optometrist Arene T. Wray in her article Optometrys Attractions for Women (January 15, 1951). (Incidentally, the white lab coat is now in the minority as well. Fewer than 36% of our readers wear one daily, as determined by a Review of Optometry Online poll in 2004.) Norman Rockwell, The Optician, 1956 SEPS, licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, Ind. Photo courtesy of Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Ma. The museum is open daily, www.nrm.org. |

From my personal observation, optometry progressed most rapidly when it had to fight. Most of us did not enjoy it at the time. However, it was good for optometry, wrote optometrist Frederick Hamilton in 1941, commenting on the very first days of the AOA.

Jump ahead to the spring of 1976. Optometry won a major victory when West Virginia passed a law that allowed qualified O.D.s to prescribe therapeutic drugs. Finally, optometrists (in West Virginia, at least) could put into practice what they had long been taught.

This legislation is not intended to make us into ophthalmologists, said John David Janney, O.D., then-president of the West Virginia Optometric Association. We know our limitations. We do not equate our training with that of an ophthalmologist. Our primary concern is the delivery of the finest care we can provide, consistent with our training.

Editor Chris Kelly, in the April 1976 editorial, phrased it in a bigger way: This new law defines optometrists as true providers of primary health care. It is to the advantage of both patient and the profession for optometry to function in this primary role. The patient can visit one office and see one doctor for the major portion of his eye care needs. And the optometrist at last can deliver the level of eye care he is being trained to deliver.

In that issue, our National Panel survey questioned hundreds of optometry students about their future as optometrists. More than 90% of them expected to be able to prescribe therapeutic drugs during their careers.

An Easy Job to Love, a Tough One to Get In reviewing the magazine over the years, several topics appear again and again. One such topic: the difficulty new graduates have in entering private practice. Here are the words of optometrist J. Robinson Cohen, then-president of the New York State Optometric Association: It has been a sorrowful experience for me to know not one, but nearly a dozen fine young optometrists who made desperate but unsuccessful attempts to establish for themselves a personal and professional practice. It has not been generally realized by the profession as a whole that we, each one of us suffered a loss when these young men failed; that each store or office closed was a double loss for optometry. On the one hand, a practice which should have been a credit to optometry was wiped out; on the other hand, the enemies of optometry gained the services of a capable, though often unwilling, tool. Sounds like a gripe you just read in an optometric chat room? It wasnt. Review of Optometry reported Dr. Cohens words in December 1936, in the midst of the Depression. Photo courtesy: Pennsylvania College of Optometry |

In the decades leading up to this watershed change in scope, Review of Optometry was already encouraging primary eye care. The magazine published articles on subjects that optometrists did not yet know about but wanted to learn and should know about. (And, we continue this tradition today.)

The methods may have changed, but the message remains the same: Optometrists should get involved in primary eye care, not just optical care, for the overall health of the patient.

|

Childrens Vision in the Formative Years Dr. King also recognized the conditions that affect vision and learning. I wish to call especial attention to a defect of sight called myopia, or near-sightedness, he wrote. This defect in many cases is acquired, and for this, the parents and the teachers are in a great measure responsible on account of our defective methods of education, especially in the height of the seats, poor ventilation, insufficient light and the desks being too flat. In January 1933, optometrist William M. Updegrave, a regular columnist in the magazine, wrote about the lack of eye exams in public schools: It is evident that the eyes are the most important avenue by which knowledge is obtained, for educators and psychologists claim that 80% of our knowledge is acquired through sight. In spite of this fact, the most important of our five senses is receiving the least consideration. At present our schools are not equipped with optometric instruments and, therefore, cannot give a thorough eye examination, which should be made of every child as soon as he enters the grades. If this were possible, not only would the teachers burden be lessened, but the worry and embarrassment of the student as well as his parents would be entirely eliminated in many instances. The student would also finish his course on schedule time, resulting in a substantial decrease in our school taxes. |

Here is but one example:

Long before optometrists were allowed to prescribe glaucoma medications, Review published an article on The Optometric Aspects of Glaucoma, (January 15, 1951). Lt. Ralph Berkely Lopez, staff optometrist at the U.S. Naval Hospital in St. Albans, N.Y., exhorted readers to get involved in this social problem of great importance. (He noted that 3,400 Americans at that time were blinded each year from glaucoma.) By and large, the optometrists of America examine the majority of the population, so therefore, it becomes the duty of each to familiarize himself with the important facts concerning the presence of glaucoma, Dr. Lopez wrote.

To that end, the article described the essential elements of the glaucoma exam: optic nerve head appearance, visual fields, gonioscopy and tonometry. But unlike other optometrists, Dr. Lopez said he had the good fortune to have a Schiotz tonometer at the naval hospital. Most optometrists didnt have any kind of tonometer. So, Dr. Lopez encouragingly described how to perform the customary procedure to gauge intraocular pressure: finger palpation of the eyeball.

Instruct your patient to look down and relax; make certain that he or she is relaxed before applying ones fingers; and then, with both index fingers placed on the upper lid, gently palpate the eyeball, he wrote. Tension may be recorded for examination purposes as tn (tension normal), +1, +2, and +3, namely as hard, decidedly hard and solid.

Dr. Lopez continued, again with avuncular reassurance: In the beginning, finger palpation may be puzzling and unsatisfactory to the examiner who is not accustomed to performing this test. The writer wishes to point out that it takes a great deal of experience to be proficient, and you can only accomplish this by doing a great number of finger palpations. The most experienced ophthalmologists will very often encounter a case that they are not sure of or that may be a borderline case. In such an event, there is only one way to determine, and that is by means of a tonometer.

Then Dr. Lopez issued a call to duty: In your optometric practice, you should perform this palpation test routinely, and if you suspect glaucoma, refer the case to a competent authority. Hundreds of cases go undetected because palpation of the eyeball is omitted in ocular examination. If you acquire the habit of performing this test, you will be amazed by the number of cases you can pick up. You then have accomplished a duty to your patient and to your profession.

|

Whats in a Name? Birth of the Optometrist

At the beginning of the 20th century, refracting opticians sought to distinguish themselves from spectacle peddlers and medical oculists. The American Association of Opticians, which was founded in 1898, adopted the term optometrist at its 1904 congress. The word comes from Latin roots to indicate one who measures the eye. The association defined optometry as the science which treats of the physiology of the functions of vision and the physical effect thereon by lenses.

Credit for introducing the term goes to Andrew J. Cross (the grand old man of optometry), John C. Eberhardt, Emanuel Klein and others, but credit for the final adoption could go to Frederick Boger. One of the points to be thoroughly discussed will be the best name to give those who professionally test eyes for refractive errors, Mr. Boger wrote in his June 1904 editorial. It is well to thoroughly discuss this question, but it seems to us that it is already settled. In issue after issue, The Optical Journal carried an illustrated design of the word optometrist, while the association carried on a campaign to popularize the term. |

Optometrys Greatest Problem

Finger palpation is no longer routine, but optometrists continue to accomplish their duty to their patients and profession. However, one dilemma has always vexed optometry, and continues to do so: its public image problem.

The problems of the optometrist cannot be solved until the public is made to understand clearly optometrys benefits, wrote optometrist W.P. Kramer in his article, How to Enlarge Your Practice, in January 1933.

|

The Peripatetic Dr. Pilgrim

Billy Pilgrim, the main character in Kurt Vonneguts revolutionary 1969 novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, is an optometrist. At one point in the story, he reads from an issue of Review of Optometry.

He also witnesses the bombing of the German city of Dresden, survives a plane crash, travels through time, gets kidnapped by aliens, and is put in a human zoo on the planet Tralfamadore. Now, who says optometrists sit on the sidelines? So it goes. |

A few months after this article appeared, editor Frederick McGill wrote an editorial that, like optometrys image problem, holds just as true today as it did then: No one enters optometry to make a fortune. A young man, he wrote, cannot expect to acquire great wealth through the practice of the profession, though he can attain moderate affluence.

Above all, Mr. McGill wrote, he can anticipate a life made happy by a degree of independence and the giving of real service to his fellow men.

|

A Turn for the Better |

Editor and founder Frederick Boger retired from the magazine in 1913. What would he think of his brainchild now?

During his tenure and afterward, Review of Optometry changed as frequently and as dramatically as the profession that it mirrors. But it remains true to Mr. Bogers dual goals of education and encouragement. Its how-to articles continue his tradition of knowing all that the textbook has taught and applying that knowledge to daily occurrences, as Mr. Boger first put it.

And its editorial stance remains single-mindedly behind optometrists. As Mr. McGill stated in a 1933 editorial: We have always fostered every movement for the benefit of the profession. We have no private, hidden axe to grind. We are free from dictation by any private interest. Our sole concern is to advance optometry to the best of our ability.

And so it is today.

|

Hindsight is 20/20 These developments are probably due in large part to the business conditions now prevailing and, as business shall improve, the bargain stores will gradually lose their appeal. The number of optometrists employed by chain corporations will then gradually decrease and the number of optometrists in practice on their own will correspondingly increase. Optometry as a profession could not be sustained if a large proportion of its practitioners were corporate employees, but the profession of optometry meets the real needs of the public, and hence obstacles in its path will be eliminated. (March 1, 1933) The Possibilities of Contact Lenses To his credit, Dr. Haussmann did suggest that plastics could revolutionize the optical industry within a comparatively short time. He also speculated that mass production would make glasses so cheap, theyd become disposable, just as we throw away our dull razor blades today. (If only he had rearranged his thoughts, he could have predicted disposable contacts.) The Importance of Hiring the Right Girl Dont Let the Medical Bug Bite |