11th Annual Cornea ReportThe April 2024 issue of Review of Optometry highlights some hot topics in cornea, from keratoconus assessment and monitoring, to advancements in endothelial surgery, to causes and treatments of corneal pain. Check out the other articles featured in this issue:

|

A wide array of corneal conditions are encountered on a daily basis in most optometric practices and appropriate diagnosis and management are vital to ensure good vision and promote ocular health. While many can be managed by practicing OD in their offices, a variety will require surgical intervention or at least a consult with a cornea or oculoplastics subspecialist. In such cases, prompt referral may be critical to ensuring successful outcomes. Here, we will detail commonly encountered corneal conditions, summarize management and underline when to consider referral.

Abrasions

Corneal abrasions occur when mechanical trauma or a foreign object scratches the epithelial surface, as well as from erosive disorders such as epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. These are frequently treated by eyecare providers and general practitioners alike. Positive sodium fluorescein staining in the setting of pain will be present, along with foreign body sensation, epiphora, redness and occasional decrease in vision.

Oftentimes, corneal abrasions can be treated conservatively with oral pain killers (if legal scope allows) and copious lubrication, although topical antibiotic prophylaxis may be warranted to prevent infections from larger, deeper abrasions with a greater extent of epithelial involvement. Bandage contact lenses should also be considered for pain relief in cases of larger epithelial defects.1,2 Generally, abrasions can be treated in-house by optometrists, although referral may be necessary for persistent epithelial defects refractory to standard treatment.

Contact Lens-induced Acute Red Eye (CLARE)

This is an inflammatory process that occurs following long-term closure of the eye in the setting of contact lens wear, as in circumstances where the patient sleeps with their lenses in. CLARE results in multiple small, focal infiltrates peripherally in the cornea with negligible overlying staining. Patents present with circumlimbal redness, epiphora, photophobia and moderate pain, typically shortly after waking with contact lenses on.

Treatment begins with a contact lens holiday, frequent lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears and topical antibiotic prophylaxis, with more severe cases requiring topical steroid drops four times daily with taper.3 Referral is generally not indicated.

Contact Lens Peripheral Ulcer (CLPU)

This is another inflammatory process that results in focal epithelial excavation with staining, infiltration and stromal necrosis. Small, focal, circular infiltrates are observed peripherally in the setting of conjunctival redness, epiphora, mild to severe pain and/or foreign body sensation, although some patients are asymptomatic. Diffuse infiltration, erosion and mild anterior chamber reaction may also be noted.

Similar to cases of CLARE, patients are treated with contact lens holiday, frequent lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears, oral analgesics as needed and close monitoring, along with topical antibiotic drops or ointment for prophylaxis.3 Severe ulceration with imminent perforation would warrant referral to ophthalmology; however, this is generally not seen with CLPU.

|

|

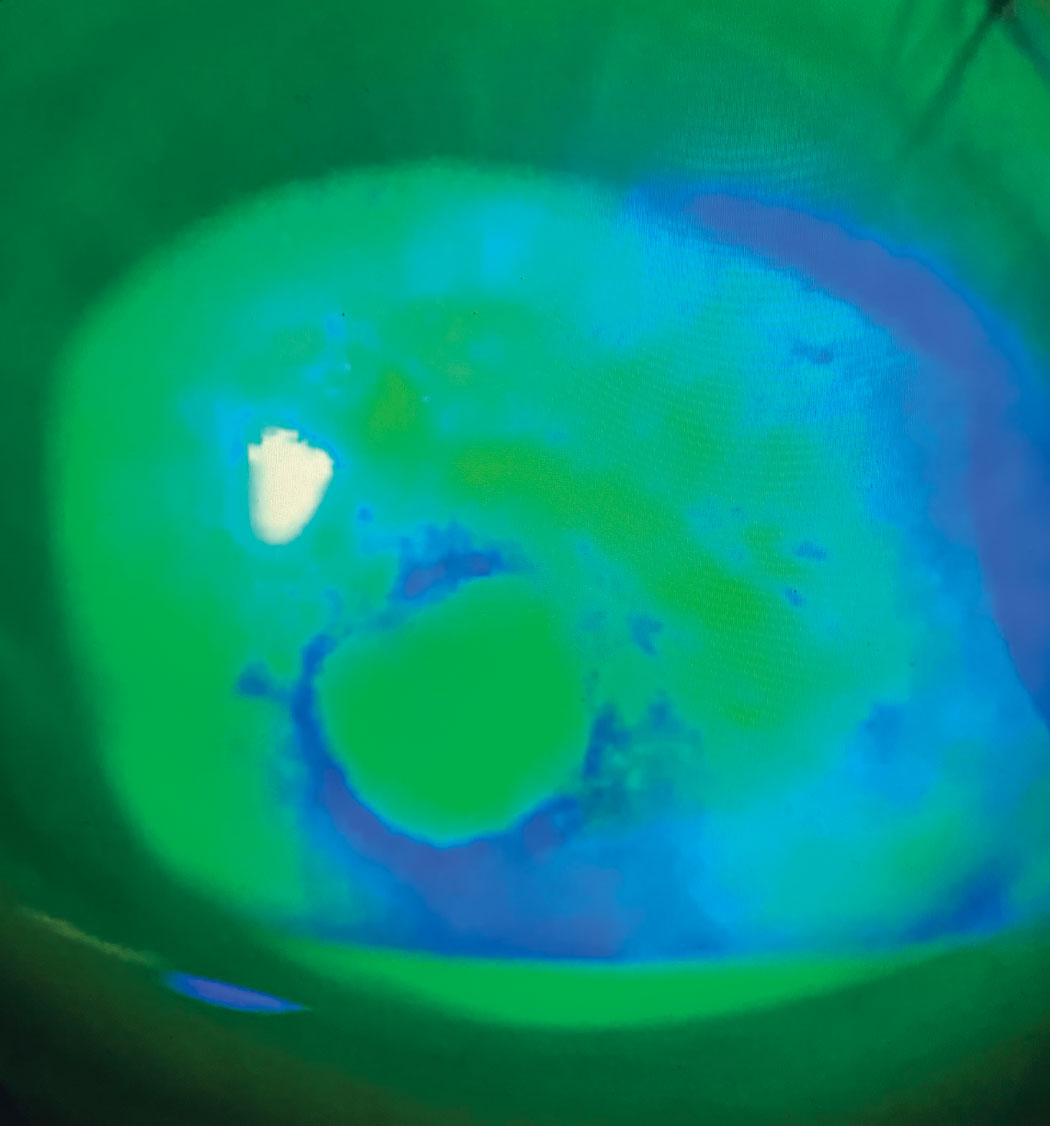

Fig. 1. Marginal degeneration. Click image to enlarge. |

Microbial Keratitis

Some of the more common etiologies for infectious keratitis are extended contact lens wear, severe ocular surface disease and ocular trauma. Pathogens and presentations can vary widely but it’s prudent to bear in mind that microbial keratitis can result in corneal opacity and vision loss if not treated promptly.4

Differentiating corneal infiltrates as sterile or infectious is critical to ensure proper treatment.5 Sterile infiltrates are often less than 1.5mm in diameter. Peripheral subepithelial or anterior stromal infiltrates with minimal overlying epithelial involvement are associated with negligible to mild symptoms. Treatment of such infiltrates includes discontinuation of contact lens wear followed by topical antibiotics, antibiotic-steroid combination agents, topical steroids or close observation. Infectious corneal ulcers often present with epithelial disruption overlying the infiltrate with acute, moderate-to-severe symptoms of pain, photophobia, vision decrease, conjunctival injection and mucopurulent discharge.

Bacterial corneal ulcers may present with a single epithelial defect overlying a stromal infiltrate with indistinct edges, corneal edema, anterior chamber reaction and hypopyon.6 Other clinical signs associated with bacterial origin include white cell infiltration of nearby stroma. If the ulcer is relatively small and non-visually threatening, empirical treatment with broad spectrum topical antibiotics such as a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone can be initiated immediately. Fortified antibiotic combinations are necessary in larger and sight-threatening ulcers, while severe cases—such as those with significant stromal thinning, corneal perforation and/or endophthalmitis—necessitate prompt referral to a cornea specialist.

In fungal etiologies, associated clinical features include multiple satellite lesions; feathery, fluffy or serrated infiltrate margins; dry, raised or necrotic infiltrates; endothelial rings and a longer clinical course history. While more rare, parasitic etiologies such as Acanthamoeba keratitis may present with pseudodendrites, perineural and/or ring-shaped infiltrates, and history of prior topical antibiotic use.7

Cultures and smears of infectious corneal ulcers are indicated when any of the following scenarios describes the infiltrates:8

• greater than 2mm in size and centrally located

• chronic, multiple or diffuse in nature

• associated by significant stromal melting

• fail to respond to empiric antibiotic therapy

• present with other signs characteristic of amoebic, mycobacterial or fungal infection

• occur in eyes with prior history of corneal surgery

Fortified antibiotic combinations are necessary in larger and sight-threatening ulcers, while severe cases, such as those with significant stromal thinning, corneal perforation, and/or endophthalmitis necessitating prompt referral to a cornea specialist.

|

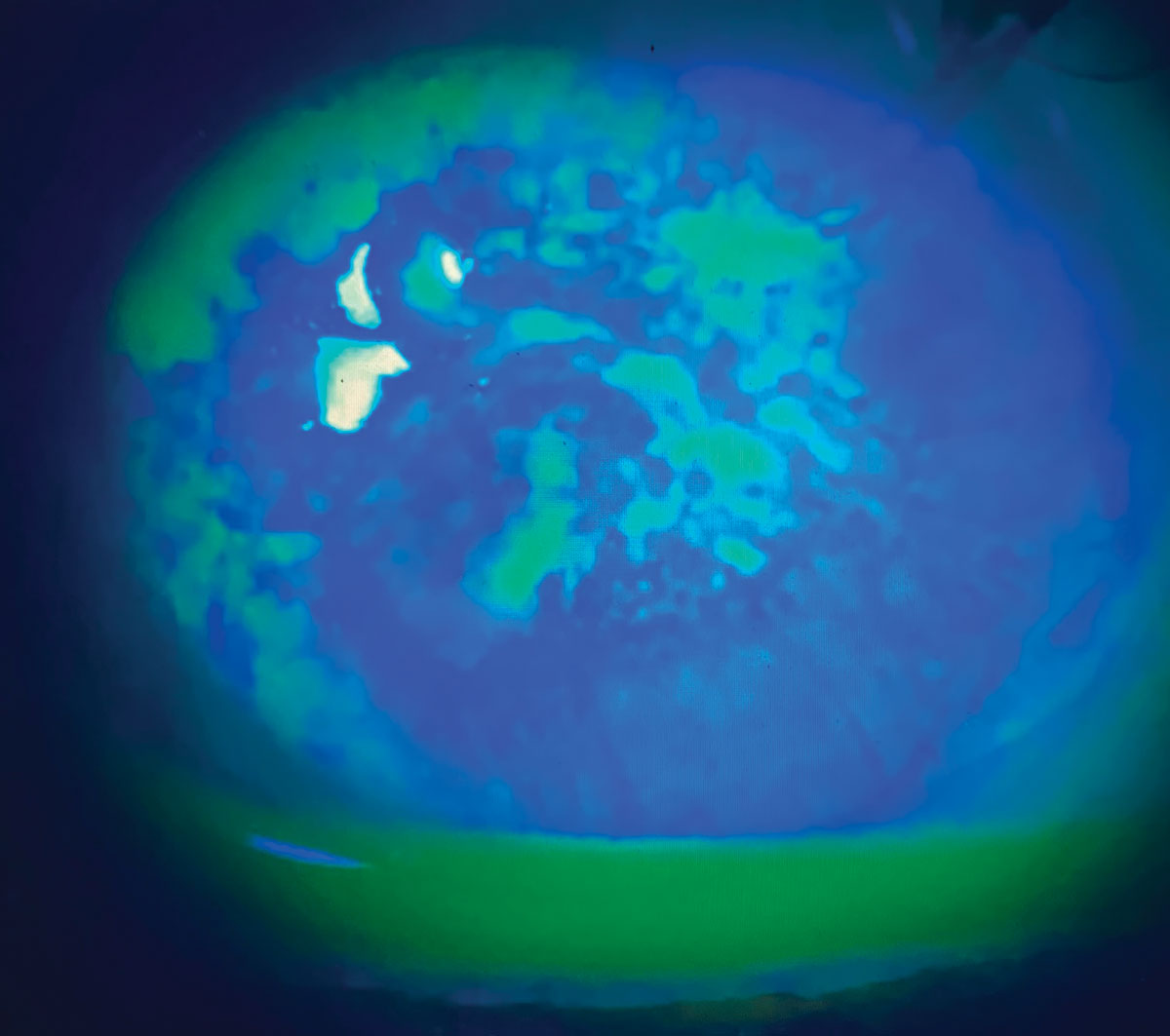

Fig. 2. Neurotrophic corneal ulcers. Photo: Joshua Keller, PharmD. Click image to enlarge. |

Viral Keratitis

The two chief culprits here are epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC) and herpetic infection. Viral corneal infections often present with symptoms of pain and photophobia, and may be accompanied by decreased vision. EKC also often presents with diffuse injection and discharge, with keratopathy and subepithelial infiltration occurring several days into the clinical course. Consider performing a betadine rinse to decrease viral load, and note that pseudomembranes must be swept every few days to prevent symblepharon formation within both the inferior and superior palpebral conjunctiva. About one to two weeks into the course of EKC, steroids are used to relieve subepithelial infiltrates and prevent scarring.

Herpetic corneal infections can result from herpes simplex virus, which may present with true dendrite branches with terminal end bulbs, interstitial keratitis or endotheliitis with keratin precipitates and stromal edema, while herpes zoster keratitis may present similarly with pseudodendritic epithelial defects, stroll haze, with or without anterior chamber reaction. The latter can be preceded by vesicular facial lesions distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve. Herpetic keratitis is treated with systemic and topical antivirals, with certain cases requiring topical steroids and/or antibiotics.9 Referral may be warranted for pain management, retinal and/or systemic involvement.

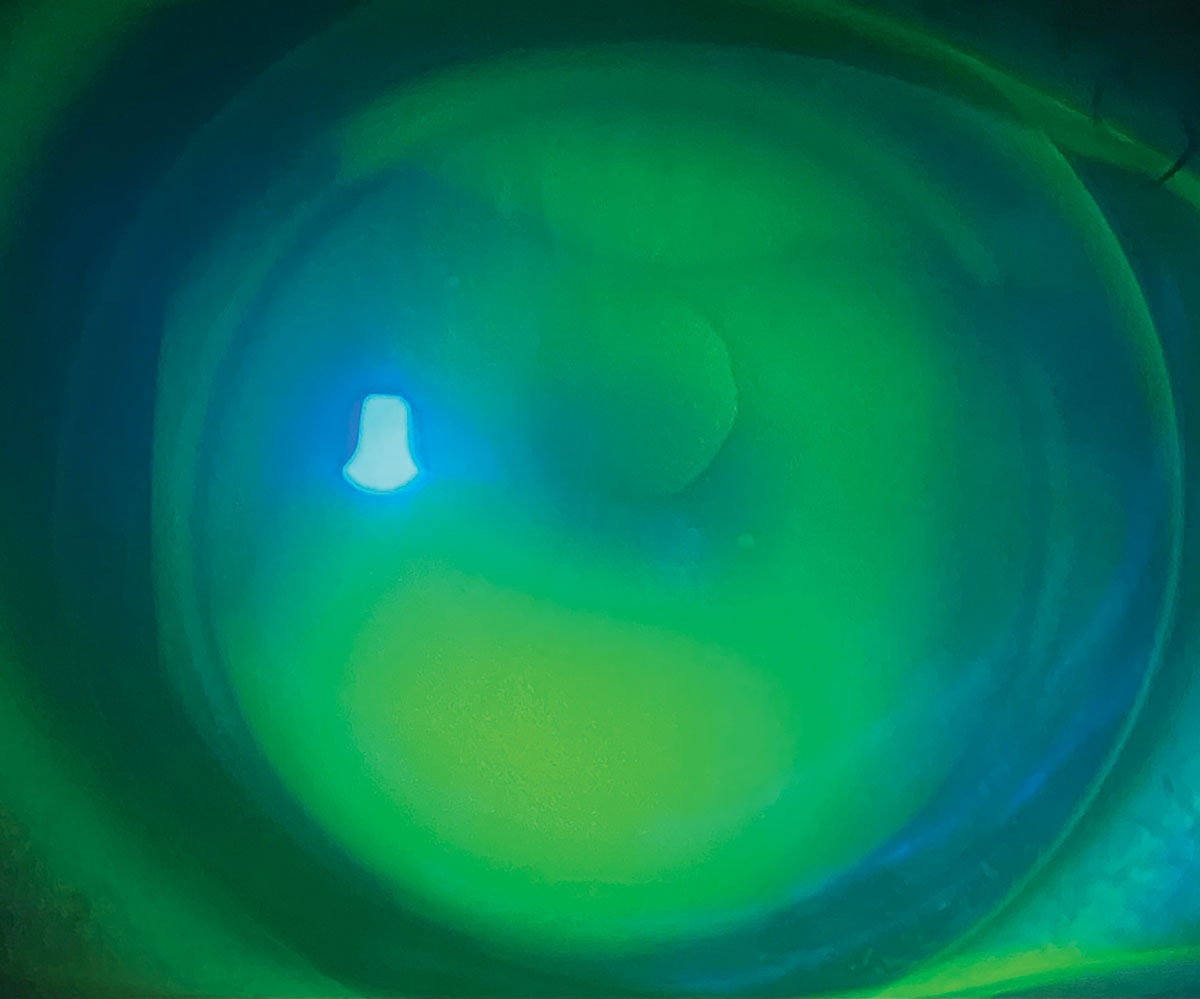

Exposure Keratopathy

When your patient’s eyelids cannot close all the way, chances are it’s exposure keratitis due to the corneal epithelium drying because of prolonged exposure, typically while sleeping. This occurs in the setting of incomplete closure due to nocturnal lagophthalmos, cranial nerve VII paresis, lagophthalmos during anesthesia, proptosis, eyelid injury and/or malformation.10 Treatment of mild-to-moderate cases includes frequent lubrication, viscous topical gels or ointments during nighttime, eyelid taping at bedtime and therapeutic contact lens wear. In severe or persistent cases, surgical comanagement with an oculoplastics surgeon is warranted to improve eyelid structure/function or for tarsorrhaphy.11

|

|

Fig. 3. Exposure keratopathy secondary to eyelid abnormality. Click image to enlarge. |

Recurrent Corneal Erosions (RCE)

These are defined as repeated episodes of epithelial breakdown following eyelid adhesion during sleep, often in the setting of prior corneal injury or with certain corneal dystrophies.12 Patients present with acute pain, tearing, photophobia and decreased vision, often upon waking, with an epithelial defect with or without loose epithelial tissue noted on exam. Treatments may include lubrication, therapeutic contact lens wear, oral tetracyclines like doxycycline, topical prednisolone, autologous serum eye drops and/or debridement of loose epithelium.

Non-healing RCEs can occur when the epithelium is loose or when medical therapy fails. After epithelial debridement and extended bandage wear contact lenses have failed, a referral might be necessary for anterior stromal micropuncture, diamond burr polishing of Bowman’s membrane or excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK). Stromal puncture is usually reserved for small areas of erosions outside the visual axis, whereas diamond burr polishing and PTK are used for larger areas of erosions.13 Some states allow optometrists to perform anterior stromal puncture if they are appropriately credentialed in the procedure. As always, use appropriate discretion.

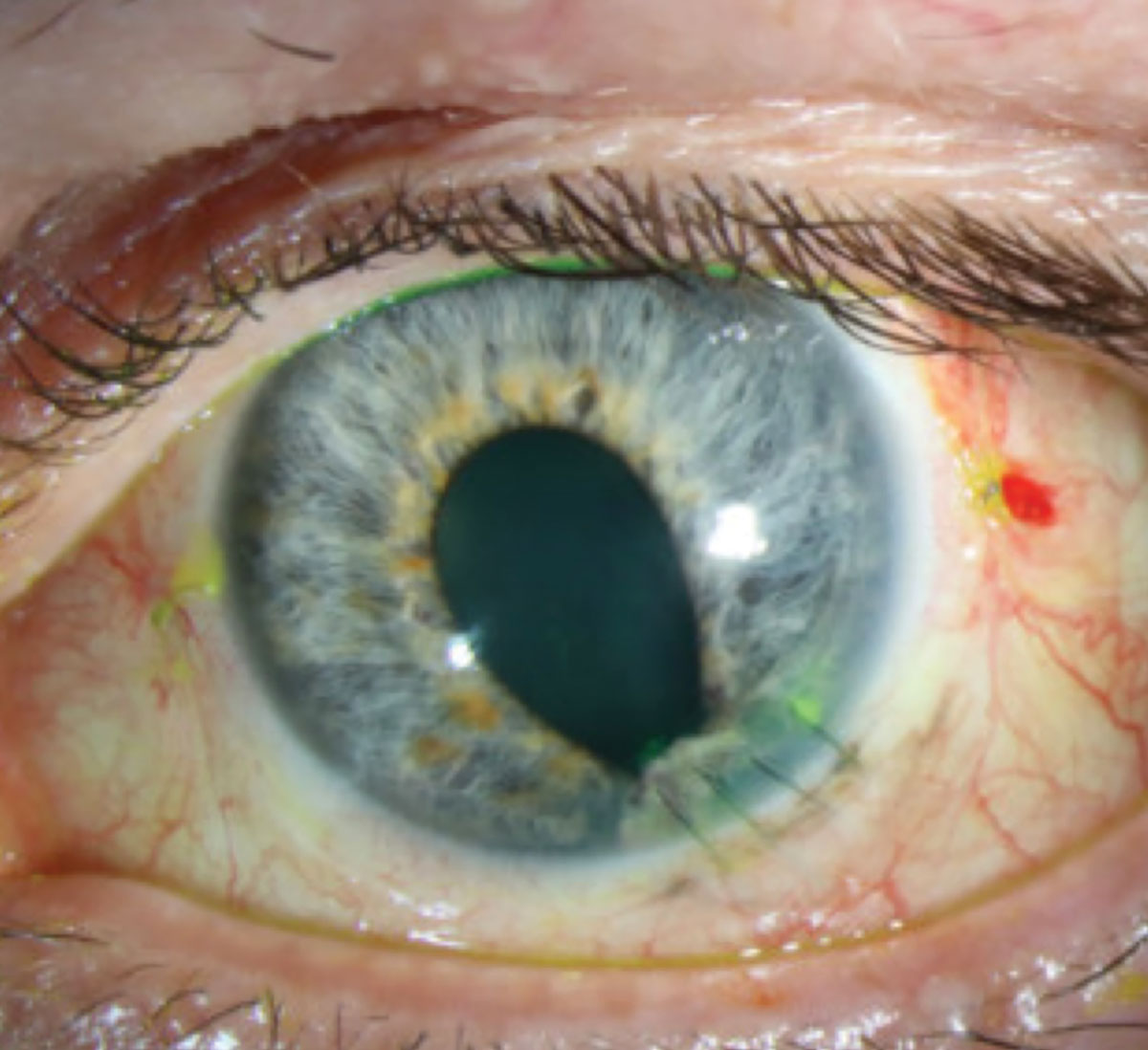

Keratoconus

This condition is a bilateral, asymmetric and progressive thinning and steepening of the cornea, resulting in irregular astigmatism and decreased vision. Patients present with blurry vision and/or ghosting (monocular diplopia). Clinical findings may include corneal thinning and steepening (often in the central or paracentral stroma), scissoring reflex on retinoscopy, Charlouex’s oil droplet reflex on dilated retroillumination, Fleischer’s ring, Vogt’s striae and apical corneal scarring. Keratoconic patterns on the axial curvature map on corneal topography confirm the diagnosis.

Mild cases can be managed with spectacles or soft contact lenses, while more moderate to advanced cases typically require specialty contact lenses or corneal transplantation, particularly if visually limiting scarring is present. In all cases, patients are educated to avoid eye rubbing. Corneal crosslinking is a minor procedure that prevents keratoconus progression by improving corneal biomechanical stability; given its favorable safety and efficacy profile, it should be discussed with all newly diagnosed cases, especially in childhood. Clear progression warrants referral to a cornea specialist.

In certain severe cases of keratoconus, a complication known as hydrops may occur in which a break in Descemet’s membrane results in corneal edema and haze. Though this condition may be self-limiting, topical hyperosmotic agents, steroids and beta blockers may expedite resolution. Corneal suturing with intracameral gas injection or tamponades may be used to promote resolution prompting referral to a cornea specialist.14

|

Fig. 4. Keratoconus managed with gas permeable contact lens. Click image to enlarge. |

Corneal Dystrophies

These diseases are generally hereditary, bilateral ocular disorders that affect one or several corneal layers and present with distinct morphologies. The conditions are slowly progressive and may result in corneal opacification.15

Optometrists are able to conservatively treat functional symptoms of corneal dystrophies such as vision loss, photophobia, foreign body sensation, pain and cosmesis concerns, as well as the sequelae of corneal erosions. This includes the use of lubrication, therapeutic contact lenses and/or hyperosmotic agents. Referral to ophthalmology is indicated when conservative measures are insufficient and it is time to consider procedures such as PK or keratoplasty.

Anterior dystrophies may end up needing similar treatments as non-healing RCEs, including anterior stromal puncture, diamond burr polishing or excimer laser PTK. Stromal dystrophies may need more invasive procedures such as superficial keratectomy, PTK, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty or a penetrating keratoplasty. Full-thickness transplants are usually reserved for severe, visually limiting corneal opacities. Posterior corneal dystrophies can often be managed without surgery; if unsuccessful, endothelial transplants are performed.

Fuchs' Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy

This is a progressive decline of corneal endothelial cells that results in apoptosis, size variation (polymegethism), shape variation (pleomorphism) and ultimately formation of excrescences called guttae.16 With time, fluid accumulates within the stroma resulting in corneal edema and vision loss.

Early FECD is typically observed with serial pachymetry and may be asymptomatic or present with reduced vision and halos upon waking. Conservative treatment includes hypertonic saline drops or ointment, as well as topical steroids. As the disease progresses, patients may experience decreased vision, photophobia, pain and epiphora if epithelial bullae rupture. Bandage contact lenses provide symptomatic relief. In more advanced cases, endothelial keratoplasty is recommended and warrants referral to a cornea specialist.

Marginal Keratitis

In this common inflammatory condition, sterile peripheral corneal infiltrates develop in the peripheral corneal abutting the eyelid margin in the setting of blepharitis.17 Patients present with symptoms of redness, photophobia and foreign body sensation and are treated with a combination of topical antibiotics and steroids, as well as lid hygiene. Referral is generally not warranted.

Corneal Burn

Chemical injury is an emergency that requires prompt treatment. Determining the causative agent is helpful to classify severity, as alkali penetrate cell membranes and are more destructive than acidic agents. Chemical exposure may result in scarring, forniceal shortening, symblephara and cicatricial ectropion/entropion. Severe burns to the limbal stem cells may cause limbal stem cell deficiency, with opacification and eventual neovascularization of the cornea.

Treatment begins with immediate copious lubrication until the ocular surface pH reaches 7.0 to 7.2. Fornices should be swept with eyelid eversion to remove particles, if present, and intraocular pressure (IOP) should be measured. For milder injuries, topical antibiotic ointment and preservative-free artificial tears are sufficient, with a short pulse of topical steroid to control inflammation. A topical cycloplegic agent may be applied for comfort, and patients should be monitored closely for improvement.

In more severe burns, a longer course of topical steroids is needed along with a longer-acting cycloplegic agent, topical broad-spectrum antibiotic and oral tetracycline, as well as high-dose vitamin C. IOP can be controlled with aqueous suppressants if needed. Significant burns may also warrant corneal debridement and amniotic membrane placement, along with referral to a specialist.18,19Perforation

A full-thickness hole in the cornea is deemed a perforation. The etiology of this can vary greatly and includes infectious, inflammatory, traumatic and medication-induced causes. Symptoms involve acute or constant tearing, redness, photophobia, pain and vision loss.

Depending on the etiology, surrounding preexisting pathology may be seen. If a shallow or flat anterior chamber involving iridocorneal touch presents, this indicates that the corneal perforation needs to be repaired within 24 to 48 hours in order to prevent severe anterior segment damage. A Seidel test may result in a positive sign. Descemet’s folds may be present in a radiating form near the perforation site. Iris prolapse may be seen incarcerated from the perforation, and the pupil may be deformed or irregular. Often the eye will feel soft on palpation; however, rarely it can be firm.

Any kind of perforation requires an immediate referral, with the size of the perforation determining the nature of the treatment. A pinpoint perforation (<0.5mm) can be treated with a bandage contact lens and aqueous suppressants. If the Seidel signs remains positive or the anterior chamber does not fill, then more aggressive treatments must be undertaken. A small or medium perforation (0.5mm to 2mm) can be treated with cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and then covered with a bandage contact lens. The cyanoacrylate glue will polymerize within seconds, forming a strong bond of the tissue, then healing and re-epithelization will take place over time. Ultimately, once the re-epithelization has occurred, the glue will dislodge. The bandage contact lens helps with patient comfort and prevents the glue from initially dislodging.

A large perforation (>2mm) that is peripheral may need a lamellar or full-thickness patch graft. Usually fresh or cryopreserved corneal or scleral tissue is used. If the perforation is large and central, a penetrating keratoplasty has to be performed.13

Interstital Keratitis

This is characterized by stromal inflammation and vascularization without epithelial involvement and can occur due to herpetic disease or congenital syphilis, although other systemic etiologies may apply. During the active inflammatory stage, patients may be symptomatic for pain, epiphora, photophobia and blepharospasm, and signs include perilimbal injection, fine endothelial keratic precipitates and concomitant iritis.

Stromal vascularization will result in ghost vessels, and corneal scarring and thinning may occur with time.20 Treatment involves topical corticosteroids; however, adjunctive treatment of topical or systemic antivirals, antibiotics or antiparasitics may be warranted for their respective etiologies, as well as treatment of systemic disease.21 Comanagement with cornea is beneficial, and systemic work-up is warranted to determine underlying pathology.

Salzmann's Nodular Degneration

This is a slow, progressive condition that is unilateral or bilateral, characterized by small, smooth gray-white elevated lesions usually on the peripheral cornea. These patients often have a history of chronic keratopathy. Often patients are asymptomatic, but when the nodules are located more central or become very elevated, they can cause decreased vision and/or a foreign body sensation. Some may do well with rigid contact lenses, or they may be referred for superficial keratectomy with a blade or excimer laser PTK with possible topical mitomycin C at the time of excision to prevent recurrence. Occasionally, lamellar keratoplasties are performed if the nodules are extremely severe.

|

|

Fig. 5. Status post-repair of penetrating corneal injury with perforation.Click image to enlarge. |

Pingueculae and Pterygia

Most of these growths on the conjunctiva can be managed conservatively, with lubrication and UV protection. They should be referred if there is any suspicion of malignancy, such as with conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia or ocular surface squamous neoplasia.

If a pterygium is visually significant or causes a constant foreign body sensation that cannot be treated topically, the patient will benefit from a referral. Surgical excision of a ptyergium is often combined with a conjunctival autograft or an amniotic membrane. Intraoperative application of mitomycin C may be used to reduce post-op recurrence but is often not necessary when a conjunctival autograft is performed. It is important these patients know and understand that pterygia can recur in about 10% to 15% of cases.Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency

This is where limbal stem cells are damaged by burns, contact lens wear, surgery, trauma or underlying genetic autoimmune conditions. Patients may experience symptoms of redness, discomfort, pain, tearing or photophobia, with vision loss in severe cases. Clinical exam may reveal epithelial stippling and progressive corneal conjunctivalization and vascularization. Partial limbal stem cell deficiency sparing the visual axis is rehabilitated with glasses or rigid contact lenses that vault over the limbus. If the visual axis is involved, amniotic membrane placement or autologous or allogenic limbal stem cell transplantation may be warranted, necessitating referral. Severe vision loss may be improved with keratoplasty (usually combined with stem cell transplant) or keratoprosthesis placement by a cornea specialist. Concurrent management of systemic and ocular comorbidities is essential.22

Neurotrophic Keratopathy

This disease stems from impairment to the trigeminal nerve secondary to systemic disease, trauma/surgery, drug toxicity, herpetic infection or contact lens wear. Impaired corneal sensation leads to impaired healing that can result in epithelial breakdown, ulceration, melting and/or scarring. Patients may present with foreign body sensation, redness, photophobia and decreased/fluctuating vision. Due to hypoesthesia, discomfort may be reduced or absent.

Treatment begins by optimizing the ocular surface by removing agents such as benzalkonium chloride and thimerosal. Address active infections with antibiotic or antiviral agents. Treat concomitant dry eye disease, blepharitis and/or inflammation with topical antibiotics and steroids, oral tetracyclines and/or topical immunomodulators, and use bandage contact lenses, amniotic membranes, autologous serum drops and tarsorrhaphy for significant punctate epitheliopathy or persistent epithelial defects. Direct treatment includes topical cenegermin drops, corneal neurotization (a multispecialty surgical procedure) and platelet-rich plasma, the latter two options warranting referral.23

Takeaways

Dr. Cherny is an instructor in ophthalmology at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai. She specializes in complex contact lens fittings, anterior segment and corneal surgery comanagement, as well as primary and emergent eye care. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. Dr. Cherny completed her resident at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, where she focused on cornea and specialty contact lenses, as well as ocular disease and emergency eye care. She graduated from the SUNY College of Optometry with a micro-credential in advanced cornea and contact lenses. Dr. Sherman is an associate professor at the University of South Florida. She specializes in complex and medically necessary contact lens fittings, anterior segment disease and primary care. Neither author has any financial interests to disclose.

1. Algarni AM, Guyatt GH, Turner A, Alamri S. Antibiotic prophylaxis for corneal abrasion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5(5):CD014617. 2. Aalam W, Barry M, Alharbi M, et al. Diagnosis and management of corneal abrasion perception of (primary health care physicians and emergency physicians) and its determinants in Saudi Arabia - a survey. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2021;28(3):151-8. 3. Sweeney DF, Jalbert I, Covey M, et al. Clinical characterization of corneal infiltrative events observed with soft contact lens wear. Cornea. 2003;22(5):435-42. 4. Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1678-89. 5. Baum J, Dabezies OH Jr. Pathogenesis and treatment of “sterile” midperipheral corneal infiltrates associated with soft contact lens use. Cornea. 2000;19(6):777-81. 6. Bourcier T, Thomas F, Borderie V, et al. Bacterial keratitis: predisposing factors, clinical and microbiological review of 300 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(7):834-8. 7. Mascarenhas J, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, et al. Acanthamoeba, fungal and bacterial keratitis: a comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(1):56-62. 8. Lin A, Rhee MK, Akpek EK, et al. Bacterial keratitis preferred practice pattern. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):P1-55. 9. Koganti R, Yadavalli T, Naqvi RA, et al. Pathobiology and treatment of viral keratitis. Exp Eye Res. 2021;205:108483. 10. Amini N, Rezaei K, Modir H, et al. Exposure keratopathy and its associated risk factors in patients undergoing general anesthesia in nonocular surgeries. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2022;15(2):175-81. 11. Koganti R, Yadavalli T, Naqvi RA, Shukla D, Naqvi AR. Pathobiology and treatment of viral keratitis. Exp Eye Res. 2021;205:108483. 12. Watson SL, Leung V. Interventions for recurrent corneal erosions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD001861. 13. Rapuano CJ. Cornea. Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology. Wills Eye Institute. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012. 14. Santodomingo-Rubido J, Carracedo G, Suzaki A, et al. Keratoconus: an updated review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2022;45(3):101559. 15. Bourges JL. Corneal dystrophies. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2017;40(6):e177-92. 16. Ong Tone S, Kocaba V, Böhm M, et al. Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy: the vicious cycle of Fuchs pathogenesis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;80:100863. 17. Jayamanne DG, Dayan M, Jenkins D, Porter R. The role of staphylococcal superantigens in the pathogenesis of marginal keratitis. Eye (Lond). 1997;11(Pt 5):618-21. 18. Dohlman CH, Cade F, Pfister R. Chemical burns to the eye: paradigm shifts in treatment. Cornea. 2011;30(6):613-4. 19. Fish R, Davidson RS. Management of ocular thermal and chemical injuries, including amniotic membrane therapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(4):317-21. 20. Knox CM, Holsclaw DS. Interstitial keratitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1998;38(4):183-95. 21. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(12):1883-95; discussion 95-6. 22. Kate A, Basu S. A review of the diagnosis and treatment of limbal stem cell deficiency. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:836009. 23. Neurotrophic Keratopathy Study Group. Neurotrophic keratopathy: an updated understanding. Ocul Surf. 2023;30:129-38. |