|

It seems impossible that an algorithm for dry eye disease (DED) diagnosis can have almost 600 scientific references and yet still be so simple every clinician can implement it, but that’s what the TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee came up with—and it works! Having been fortunate to serve on this committee, I can tell you firsthand it’s a practical approach that streamlines your efforts and increases diagnostic accuracy.

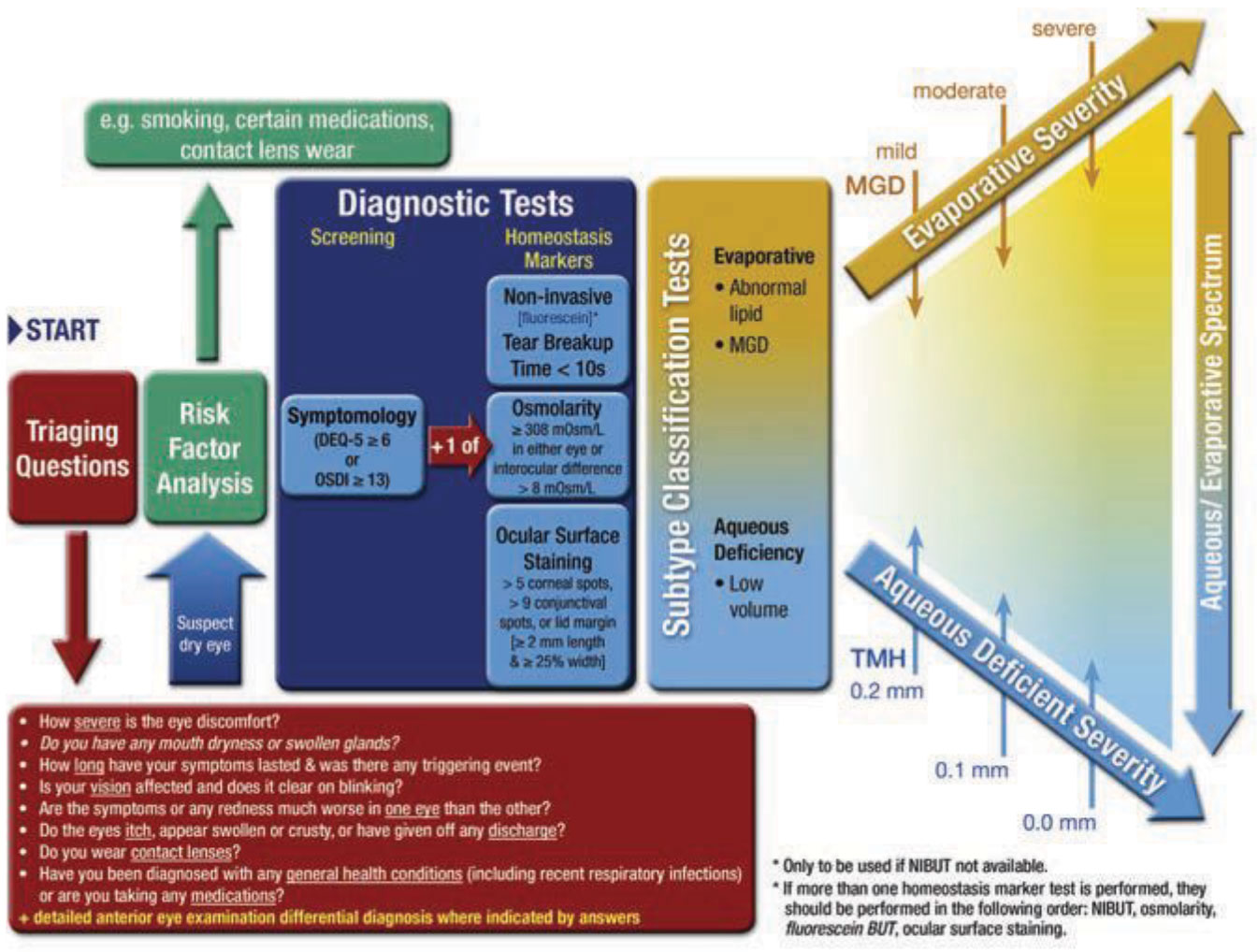

The first thing you have to recognize is that DED requires both a sign and a symptom to make the diagnosis. For example, an extreme sign like punctate epithelial keratitis without symptoms isn’t dry eye—it’s likely neurotrophic keratitis. Let’s look at the five key steps in this diagnostic methodology.

|

|

The TFOS DEWS II dry eye diagnostic algorithm at a glance. Click image to enlarge. |

1. Ask Triaging Questions

The first action in identifying DED is to ask a series of triaging questions. My favorite ones came from the Optometric Dry Eye Summit, which took place in Denver in 2014, although the TFOS DEWS II report, released in 2017, has far more examples. Somewhat paraphrased, these questions are:

- How do your eyes feel? (i.e., are they dry, gritty, light sensitive, burning or stinging?)

- How do your eyes look? (i.e., are they red or look irritated?)

- Do you experience fluctuating vision?

- Do you use, or have the urge to use, artificial tears or rewetting drops?

- How much time do you spend on digital devices?

2. Assess Risk Factors

Next, look at the risk factors. The list includes use of various medications like oral antihistamines and topical glaucoma medications, as well as history of contact lens wear, previous ocular surgery and autoimmune conditions such as thyroid disease, diabetes, arthritis, smoking and others.3. Inquire about Symptoms

Essential to a dry eye diagnosis is how the patient feels. Any of the following could indicate DED: dryness, grittiness, burning or stinging, tearing, foreign body sensation, itching, contact lens intolerance, fluctuating or blurred vision, hyperemia, photophobia and pain/discomfort.2

Although eye dryness is likely the best single indicator—after all, it’s right there in the name of the condition—a few others that stand out are fluctuating vision, tearing (epiphora) and hyperemia. In fact, if you are refracting a patient and the image clears and then blurs with each blink, consider DED. Tearing is difficult for patients to assess, as they can’t understand how “dry” eye could cause excess tears. What typically occurs is meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) and the body’s response to it is reflex tearing, so an explanation of mechanisms to the patient is warranted. The last indicator is hyperemia, which is often noted by patients and indicates inflammation, also strongly associated with DED.

An easier way to assess symptoms is having the patient take a validated questionnaire before examination. The TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Committee recommends the DEQ-5, and other options include the SPEED or OSDI questionnaires. The benefit of this step is that it provides a score that can be monitored for changes over time.

|

|

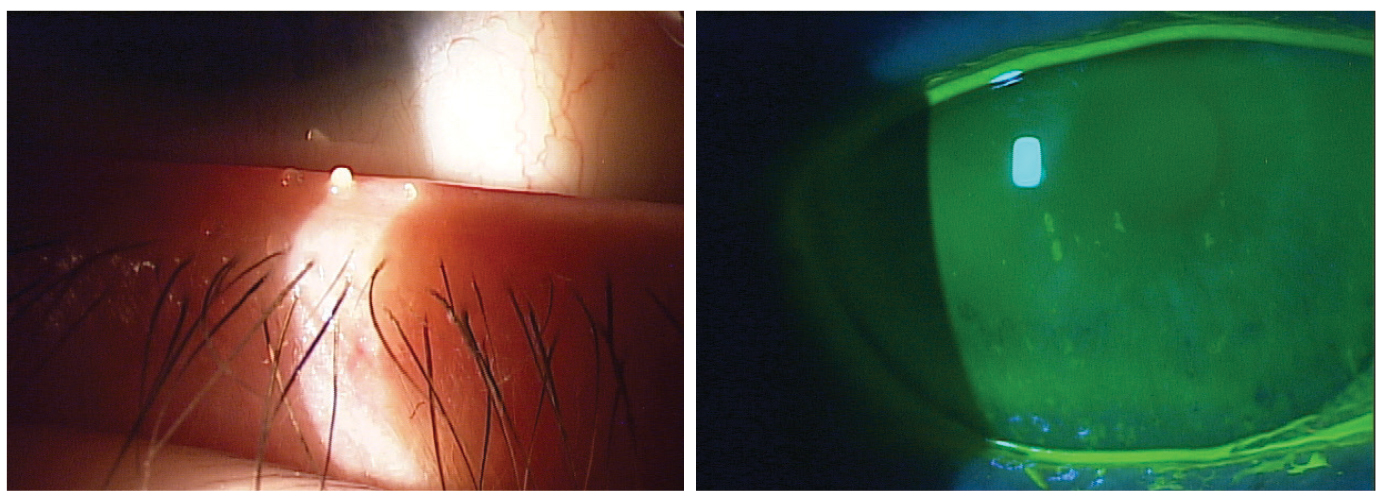

Evaporative DED, a consequence of MGD (left), and aqueous-deficient (right) and are the two primary types of dry eye. Click image to enlarge. |

4. Identify Signs

To help in the diagnostic flow, the committee broke out diagnostic tests between global homeostasis testing and subtyping of DED. In other words, a failed homeostasis test indicates the presence of DED (if symptoms are also present) but classifying dry eye further is still required. The three homeostasis tests to consider are osmolarity testing, ocular surface staining and tear film break-up time (TFBUT). Although the paper suggests using one of the three, I think two of three is still rather efficient and increases accuracy.To assess osmolarity, bear in mind that if the patient has a reading under 300mOsmol/L and each eye is within 6mOsmol/L of the other (e.g., osmolarities of 291 OD and 293 OS), the patient likely doesn’t have dry eye disease.3 A reading over 308mOsmol/L or significant instability between eyes is indicative of DED.4,5

Ocular surface staining involves observing both the cornea and conjunctiva for superficial punctate keratitis, and the recommended approach is a noninvasive TFBUT.

Once one of these is positive, you have signs to go with symptoms and a diagnosis of DED is made.5. Find the Subtype

Finally, we need to determine the type of dry eye so that you can begin appropriately targeted treatment. There are two primary types—evaporative and aqueous-deficient—but overlap can occur. Evaporative DED is a consequence of MGD, while aqueous-deficient DED refers to issues involving the lacrimal glands and/or mucin producing goblet cells.To determine if a patient has evaporative DED, simply express the meibomian glands. While at the slit lamp, use a Mastrota Meibomian Paddle, Collins forceps, wet Q-tip or your fingers to gently press on the lower nasal to central eyelid. Normal expression should be clear and thin like olive oil. Abnormal is turbid, thickened, paste-like or non-expressive.

To determine if it is aqueous-deficient DED, look at the lower tear meniscus height while the NaFl is present. Any measurement under 0.2mm is considered abnormal.

Over to You

There, you’ve just saved yourself from reading more than 50 pages of the TFOS DEWS II report—although I do believe it is well worth reading for those who want a deeper dive!

Dr. Karpecki is medical director for Keplr Vision and the Dry Eye Institutes of Kentucky and Indiana. He is the Chief Clinical Editor for Review of Optometry and chairman of the affiliated New Technologies & Treatments conferences. A fixture in optometric clinical education, he provides consulting services to a wide array of ophthalmic clients. Dr. Karpecki’s full disclosure list can be found here.

| 1. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. OD TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Report. Ocul Surf. 2017; 15(3): 539-74 2. Belmonte C, Acosta MC, Merayo-Lloves J, et al. What causes eye pain? Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2015; 3(2): 111-21. 3. Bron AJ, Tomlinson A, Foulks GN, et al. Rethinking dry eye disease: a perspective on clinical implications. Ocul Surf. 2014 Apr;12(2 Suppl): S1-31. 4. Sullivan BD1, Crews LA, Messmer EM, et al. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014 Mar; 92(2): 161-6. 5. Sullivan BD1, Whitmer D, Nichols KK, et al. An objective approach to dry eye disease severity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 Dec;51(12): 6125-30. |