|

Neurotrophic keratitis (NK) is a corneal degenerative disease characterized by reduced corneal sensation, chronic superficial keratopathy (SPK), persistent epithelial defects and other corneal changes. Although an “orphan disease” affecting fewer than five people out of every 10,000, NK is quite challenging to manage when it presents. Untreated or undertreated, it can have serious consequences for vision and quality of life.

|

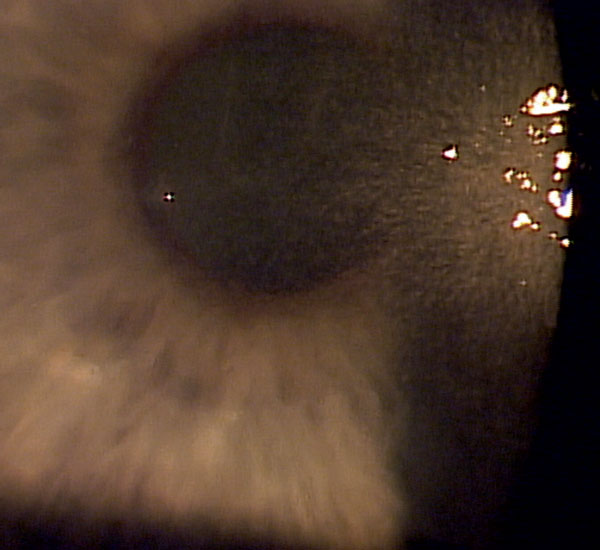

| Fig. 1. Neurotrophic keratitis in a patient with herpes simplex keratitis. |

NK Basics

The cornea and corneal epithelium are densely innervated by nerves originating from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal (fifth cranial) nerve. In fact, the cornea has 7,000 nerve receptors per square millimeter, making it one of the most sensitive structures in the body.1 Those nerves are responsible for nociception (pain perception) and sensation of cold and pressure. They are part of complex feedback loops that signal tear production, the blink reflex, the production of trophic factors that provide nutrition to the cornea and the release of immune factors into the tears.1

Infrequent blinking and reduced tear production in NK exacerbate the condition, leading to an inflamed ocular surface and further epithelial damage. When epithelial healing is compromised, the exposed stroma becomes more vulnerable to enzymatic degradation and, eventually, ulceration or even perforation.3

NK is most commonly associated with herpetic keratitis (either herpes zoster or herpes simplex), post-neurosurgical nerve damage and diabetes (Figure 1).1,4 It may also be caused by chemical burns, contact lens misuse, long-term exposure to preserved medications, overuse of topical anesthetics and, less commonly, with tumors, leprosy and certain genetic conditions.1

Presentation and Examination

One study recently proposed a simplified classification of NK: mild, denoted by epithelium and tear film changes; moderate, accompanied by a non-healing epithelial defect; or severe, in which stromal melting and perforation occur.1 These three stages are clinically useful for understanding the severity of disease and potential treatments.

In patients presenting with early to mid-stage NK, it is common to see significant staining or SPK and epithelial defects that don’t heal properly, as well as rapid tear break-up time and reduced or fluctuating visual acuity. However, patients will often be far less symptomatic than you would expect due to the reduced corneal sensation. As the disease progresses, corneal thinning, ulceration and even perforation occur.

In patients presenting with these signs and symptoms, optometrists should carefully evaluate the lid anatomy and function, including closure and blink rate. If you suspect NK, assess corneal sensation by using either a cotton wisp or acrylic dental floss applied to the cornea. You could also use an esthesiometer. Staining with vital dyes is important for visualizing ocular surface damage (Figure 2). Suspicion of underlying brain pathology or systemic disease may warrant a referral to internal medicine or neurology.

|

| Fig. 2. Vital dyes are key diagnostic tools to help clinicians visualize ocular surface damage from neurotrophic keratitis. |

Treatment

NK has always been a challenging condition to treat. Until recently, we have had few good options, especially for patients with moderate disease in particular.

As a first step, clinicians should minimize ocular irritants. Eliminate all preserved topical drops (if possible) by reducing medications or switching to non-preserved forms.5 Regular use of artificial tears and other lubricants, punctal occlusion, increased humidity and dietary omega fatty acids can all be helpful as well. Research shows autologous serum drops (e.g., Vital Tears) improve signs and symptoms and significantly shorten healing time for, and recurrences of, corneal defects.6 Clinicians may need to debride any thickened or rolled edges of epithelial defects.7 A bandage contact lens can be helpful but also increases the risk of infection.2 A better option might be amniotic membrane. One study using Prokera (BioTissue) showed a statistically significant improvement in nerve density and sensitivity when analyzing the corneal nerves under confocal microscopy.8 These patients also showed improvement in corneal staining, symptoms of pain and SPEED scores.8

Nonsurgical eyelid closure with tape, pressure patching or temporary ptosis with botulinum toxin can help to protect loose epithelium and while epithelial defects heal.

It is also important to treat concurrent infection, inflammation or meibomian gland dysfunction with appropriate therapies, such as antibiotics, cyclosporine, lid expression and lid hygiene.

In more advanced stages of the disease, a number of strategies can help to restore corneal integrity or, for the most extreme stages, prioritize globe integrity over vision. These include temporary or permanent tarsorrhaphy, use of corneal tissue glue, amniotic membrane graft, Boston keratoprosthesis, lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty and a partial or total conjunctival flap (Figure 2).9 Eyes with NK have a higher than usual rate of failure for corneal surgery.2

Treatment Advances

The FDA recently approved a new treatment for NK that is expected to launch commercially in early 2019. Oxervate (cenegermin-bkbj ophthalmic solution 0.002%, Dompé) is a recombinant form of human nerve growth factor that targets the nerve pathology.10 In two randomized double-masked controlled trials, 151 subjects received cenegermin or vehicle six times daily for eight weeks. Complete corneal healing was demonstrated in 70% of the 101 patients treated with Oxervate compared with only 28% of those treated with the control drop.1,11,12

The most common adverse reaction was eye pain following instillation, which was reported in approximately 16% of patients. Other adverse reactions included corneal deposits, foreign body sensation, ocular hyperemia, ocular inflammation and tearing.12,13

Oxervate will be somewhat more challenging for patients to administer than the average topical medication. A week’s supply of the medication, frozen, must be shipped directly to patients, who will thaw one of the seven multidose vials each day and store in the refrigerator between doses. Instructions will be provided for attaching an adapter to the vial, cleaning the adapter with a sterile wipe, attaching a special pipette with a plunger mechanism, and then releasing the drop from the plunger to administer one drop every two hours, six times a day.13 Although the steps may be cumbersome, mastering them is worthwhile, considering cenegermin holds greater potential than most of the treatment options we have for NK.

There are several other biologics and other therapies in practice and in the pipeline, including Xiidra (lifitegrast 5%, Shire), regenerating matrix therapy agent cacicol-20, thymosin beta 4, coenzyme Q10, substance P, netrin-1 and Nexagon (CoDa Therapeutics), an antisense oligonucleotide.

With these new therapies, we can be far more encouraged than ever before about our ability to successfully manage patients with NK.

1. Dua HS, Said DG, Messmer EM, et al. Neurotropic keratopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;66:107-31. 2. Srinivasan S, Lyall DAM. Neurotrophic keratopathy. In: Ocular Surface Disease: Cornea, Conjunctiva, and Tear Film. Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, Lee WB, eds. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2013. 3. Fini ME, Cook JR, Mohan R. Proteolytic mechanisms in corneal ulceration and repair. Arch Dermtol Res. 1998;290(Suppl 1):S12-23. 4. Allen VD, Malinovsky V. Management of neurotrophic keratopathy. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2003;26(3):161-5. 5. Gomes JAP, Azar DT, Baudouin C, et al. TFOS DEWS II iatragenic report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:511-37. 6. Guadilla AM, Balado P, Baeza A, Merino M. Effectiveness of topical autologous serum treatment in neurotrophic keratopathy. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2013;88(8):302-6. 7. Katzman LR, Jeng BH. Management strategies for persistent epithelial defects of the cornea. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014;28:168-72. 8. John T, Tighe S, Sheha H, et al. Corneal nerve regeneration after self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane in dry eye disease. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6404918. 9. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-95. 10. Bonini S, Lambiase A, Rama P, et al., REPARO Study Group. Phase I trial of recombinant human nerve growth factor for neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(9):1468-71. 11. Sacchetti M, Bruscolini A, Lambiase A. Cenegermin for the treatment of neurotrophic keratitis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2017;53(11):585-95. 12. Bonini S, Lambiase A, Rama P, et al., REPARO Study Group. Phase II randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled trial of recombinanat human nerve growth factor for neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(9):1332-43. 13. Oxervate Prescribing Information (PI). www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761094s000lbl.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2019. |