|

A 68-year-old Caucasian male presented to the eye clinic for a comprehensive eye exam with a complaint of blur while reading. He explained that he liked to wear separate distance and near vision glasses and was hoping we could improve things. He denied any personal or family history of glaucoma or macular degeneration. His systemic history was remarkable for sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease and hepatitis C, all of which he was properly medicated for. He reported allergy to penicillin and codeine.

Clinical Findings

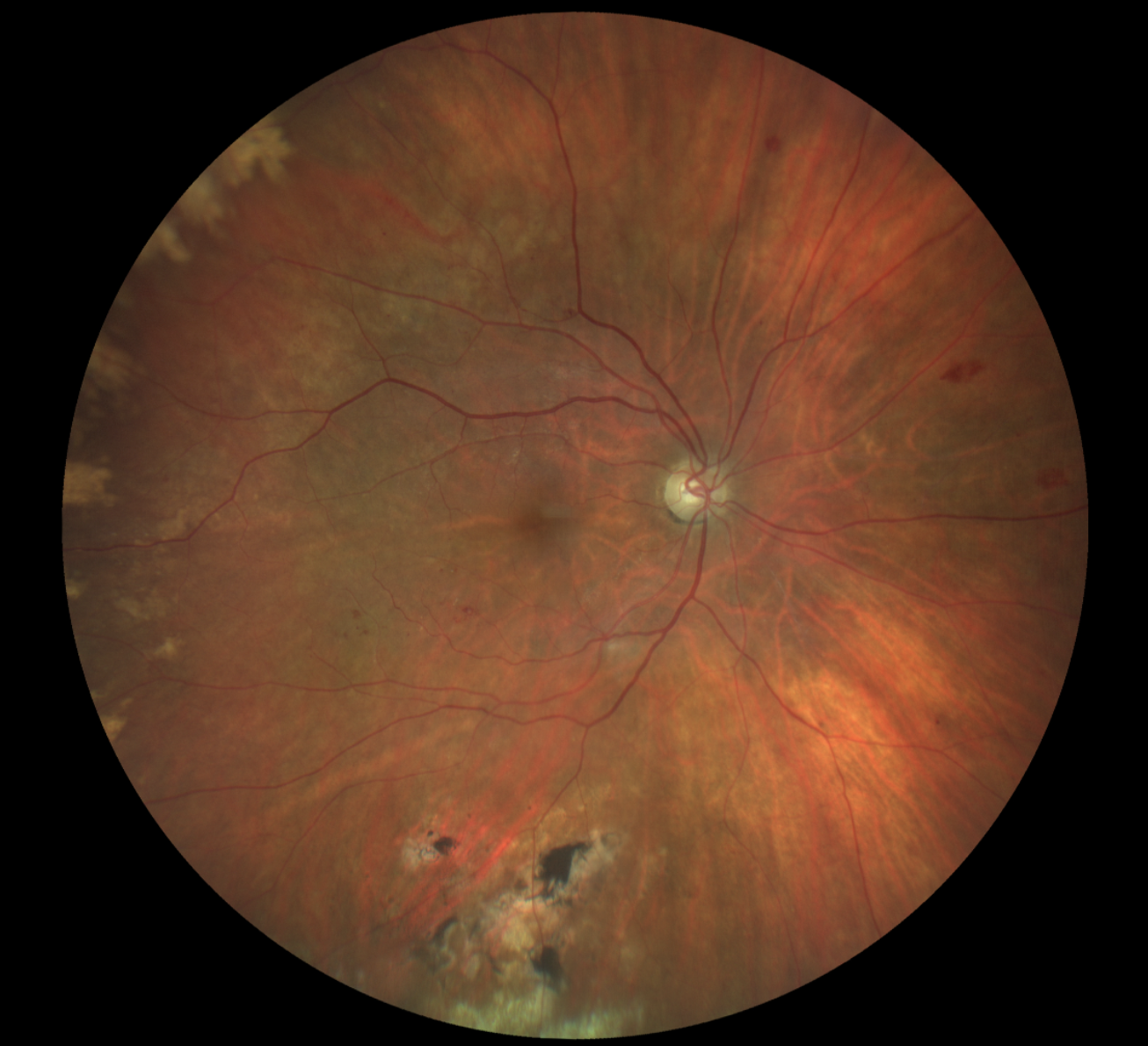

His best-corrected entering visual acuity was 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS at distance and near through +1.00/+2.25 spectacles. External testing was unremarkable, with normal confrontation fields and no afferent pupillary defect. Near vision was improved with a +2.75D addition. Anterior segment evaluation was normal and Goldmann applanation tonometry measured 15mm Hg OD and 14mm Hg OS. The pertinent fundus findings are demonstrated in the photograph.

Additional studies in this case might include B-scan ultrasonography to rule out mass lesions or detachments, fluorescein angiography to assess retinal circulation and a retina referral for treatment considerations.

|

|

Does the appearance of the patient’s peripheral fundus bring to mind any potential diagnoses? Click image to enlarge. |

What would be your diagnosis in this case? What is the patient’s likely prognosis?

Diagnosis

The diagnosis in this issue is peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) of the left eye. This condition was first reported by Annesley in 1980. He described the lesion as a sub–retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) accumulation of blood and exudates typically seen in elderly patients with hypertension and arteriosclerotic disease.1

More recent studies have established that about half the patients with this condition also have a history of long-term anticoagulant therapy.2,3 PEHCR has a predilection for Caucasian females with the average age of diagnosis being 80 years.2,3 The condition is most commonly found in the temporal periphery with bilateral presentation observed in 30% of cases.2-4 The pathophysiology of the condition is similar to that of its “centrally seen” vision-threatening counterparts exudative age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.4,5 Due to its infrequent presentation and the asymptomatic nature of the condition, coupled with the inherent difficulties of the peripheral retinal exam, PEHCR often goes undiscovered.

However, PEHCR is the second most common lesion referred for suspicion of choroidal melanoma (choroidal nevus being the first).2,3 In fact, Shields et al. conducted a study in 2009 on 173 eyes with PEHCR due to the number of referrals they received.3 The goal of the study was to establish criteria that help distinguish PEHCR from melanoma by characterizing the clinical features and evaluating progression over time.

The group reported that PEHCR lesions tend to be 10mm in diameter and 3mm in thickness, spanning more than one quadrant, with the most common location being in the temporal periphery between the ora and equator.4 Choroidal melanomas, by contrast, typically present between the macula and equator and occupy less than one quadrant.4 In their study, 42% of PEHCR patients were asymptomatic; those who were symptomatic reported variably decreased vision, flashes and floaters. Peripheral RPE changes and drusen were found in 69% of eyes with PEHCR, suggesting that the condition is the result of age-related degenerative processes in the peripheral retina.3,5

B-scan ultrasonography and fluorescein angiography are useful for differentiation of PEHCR. The B-scan typically demonstrates a dome-shaped elevation with high internal reflectivity, whereas a choroidal melanoma is acoustically hollow.2,4 A fluorescein angiography of PEHCR will show blockage of choroidal fluorescence (hypofluorescence), while choroidal melanomas are hyperfluorescent.2-4

Shields et. al. found that after 15 months of follow-up, 89% of PEHCR cases showed regression or stability, while 11% progressed into a recurrent or new lesion. About 8% of patients developed central exudative macular degeneration and 6% developed a posterior vitreous hemorrhage in the affected eye.4-7 The literature finds PEHCR to be responsive to anti-VEGF injections, but the treatment is not considered standard of care for asymptomatic cases at this time.4-7 Considering that a majority of PEHCR lesions resolve spontaneously, leaving behind RPE atrophy and fibrosis, the most appropriate management for this condition is observation.

Conclusion

This patient was referred to a retina specialist, who concurred with the diagnosis and recommended observation with routine dilated eye exams.

Dr. Gurwood thanks Saidivya Komma, OD for contributing this case. She is an attending optometrist and externship coordinator at the Kernersville VA Medical Center. She has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Gurwood is a professor of clinical sciences at The Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. He is a co-chief of Primary Care Suite 3. He is attending medical staff in the department of ophthalmology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Annesley WH. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1980;78:321-364. 2. Vandefonteyne S, Caujolle JP, Rosier L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of peripheral exudative haemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;104(6):874-878. 3. Shields CL, Salazar PF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy Simulating Choroidal Melanoma in 173 Eyes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):529-535. 4. Mazal Z. Peripheral Exudative Heamorrhagic Chorioretinopathy. Czech and Slovak Ophthalmology. 2019;75(2):80-84. 5. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy: A Variant of Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy? Journal of Ophthalmic & Vision Research. 2013;8(3):264-267. 6. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2012;6:865-869. 7. Sax J, Karpa M, Reddie I. Response to intravitreal aflibercept in a patient with peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Retinal Cases and Brief Reports. 2021;15(3):286-288. |