Who is Your Patient?This series explores how both innate and acquired elements of identity manifest in the clinic:

|

Working with pediatric patients can be intimidating, but is the most fun and rewarding experience. It can be somewhat daunting from the get-go when a child and parent enter an optometrist’s office due to parents not knowing what to expect and not exactly looking forward to receiving potentially life-changing news about their child’s condition. When it comes to the kid patients, they can at times be undisciplined, may have trouble sitting still and have to be engaged from the moment they walk through the door.

For a pediatric exam, we ultimately need the same information that we collect during an adult exam; we just use creativity and varied methods to obtain that same base data set. Simplifying the initial approach down to the basics of an eye exam can make a pediatric work-up protocol significantly more approachable for both doctors and staff.

In this article—the first of a four-part series on pediatric care—we will talk about specific ways to add fun and lightness to a sometimes intimidating experience for the patient and their parent, and discuss the best ways to perform an exam on the youngest of patients.

Exam Early

Over the last few years, I have seen a significant increase in the number of patients referred for formal evaluation from both doctors’ offices and school districts. This is largely because of an increase in availability and accuracy of photo-screener technology, and also possibly because of an increase in technology use in classrooms.

In the absence of a photo-screener alert from a pediatrician or school, children may benefit from having a baseline dilated eye exam by age three. This ensures that as they are exposed to visual language, they can interpret their visual world as accurately as possible and we can treat amblyopia if amblyopic factors are found.

|

|

An optometrist is making this eye exam fun for a young patient. |

This is also an important age for dilated fundus evaluation for potentially life-threatening diseases such as retinoblastoma. In your local community, communicating with pediatricians, alerting daycares and schools and talking with peers can increase the number of children who receive eye care.

Interactive Items

Waiting rooms are our patient’s initial impression of what will be happening to them, if their parent hasn’t primed them with a description of their eye exam.

Right now, our office does not have toys out, as these are high-touch items that encourage movement and that we cannot effectively disinfect at this time. In an ideal world, and maybe again in the future, pediatric patients are greeted by colorful, interactive toys to help them stay relaxed and enjoy their experience.

|

|

Having colorful, interactive items and toys in your waiting room will keep pediatric patients engaged and relaxed as they wait for their appointment. |

How to Perform an Exam

The challenge of a pediatric exam comes from obtaining necessary data in a way that minimizes frustration of the patient and the staff member. Doctors and staff must be ready to see pediatric patients, both in terms of equipment and mindset. All you technically need is a retinoscope and a BIO, but additional tools and forethought can provide cooperation and comfort of your patient and their parent significantly.

Some offices I travel to are not equipped with a full array of peds tools. In those cases, we have a “peds bucket,” which typically includes stickers, a spinning light, adhesive patches, stereo booklet and glasses, loose prisms and a talking Elmo doll. Any of these items or substitutes can be found easily and kept around the office to set you up for success in maintaining pediatric patients’ attention.

Pre-testing: Stickers, spinning light toys and small toys can transform the success of your data acquisition with pediatric patients. A child is far more likely to follow a fun light when you ask them, “What colors do you see?” or to fixate on a sticker when you can say, “Does this look like a happy elephant?” than to follow our typical adult script. Having toys and stickers allows you to connect with the patient and can decrease the harshness of being at the doctor’s office.

|

|

A young patient during a pediatric eye exam. |

Acuity: We aim to test visual acuity with as advanced a technique as the patient is capable of; that does not mean the patient has to be able to read the chart. The hierarchy ranges from Snellen with our verbal patients who know letters, to Lea symbol charts and matching, to central, stead and maintained; to blink to light and an optokinetic nystagmus drum. We operate with a majority of our pre- or non-verbal patients getting an allocation of central steady and maintained or central steady and fixated visual acuities. Teller acuities, used in research and academic settings, aren’t as functional for your high-volume clinic setting.

Dilation: I cannot pretend to be the expert in this topic, as I rarely dilate a patient on my own. In most circumstances, my wonderful technicians dilate my patients to reduce the possibility of a breakdown when I re-enter the room for retinoscopy. When my technicians are kind enough to play the “bad guy” and administer drops, they generally agree that speed is on their side. They do a great job of reading the room and determining the patient’s level of anxiety surrounding the drop administration process.

In the case of a very alert child who may have sensory sensitivities, further explanation may be helpful. In other cases, asking the patient if they want cherry or apple flavored eye drops—and administering quickly—may be the most effective, rather than drawing out the process with an explanation.

In all circumstances, we respect the patient’s bodily autonomy, but there are times that a big hug by the parent to prevent scratching and kicking makes our drop delivery more successful.

Once dilated, the provider performs retinoscopy and posterior segment exam (BIO) on all patients, and slit lamp exam is typically performed for patients four years old and above (we can manage slit lamp on infants if the patient’s caregiver is willing and we deem it important).

Retinoscopy: In our office we use loose lens retinoscopy with sphere and cylinder lens combinations for neutralization. During retinoscopy, I tend to sing a song with or to the patient to maintain their gaze. My counterpart is less prone to singing, so he will make “mouse noises” behind the retinoscope or have a technician hold up a spinning light or Elmo doll beside his head to maintain fixation long enough to find an accurate neutralization of refractive error.

You will inevitably find yourself performing retinoscopy on a screaming, inconsolable toddler at some point, but having these tools and an ability to not take yourself too seriously to sing nursery rhymes can reduce that likelihood significantly.

I do not prescribe a final glasses prescription without retinoscopy obtained after a dilating agent. When new patient parents come into our office not wanting their children dilated, our technicians are well-versed in respectful ways to discuss why we encourage it. When necessary, I will enter the conversation and emphasize that we cannot:

(1) accurately assess refractive error, and therefore how it affects binocular vision;

(2) fully evaluate posterior segment health, without dilating agents.

|

|

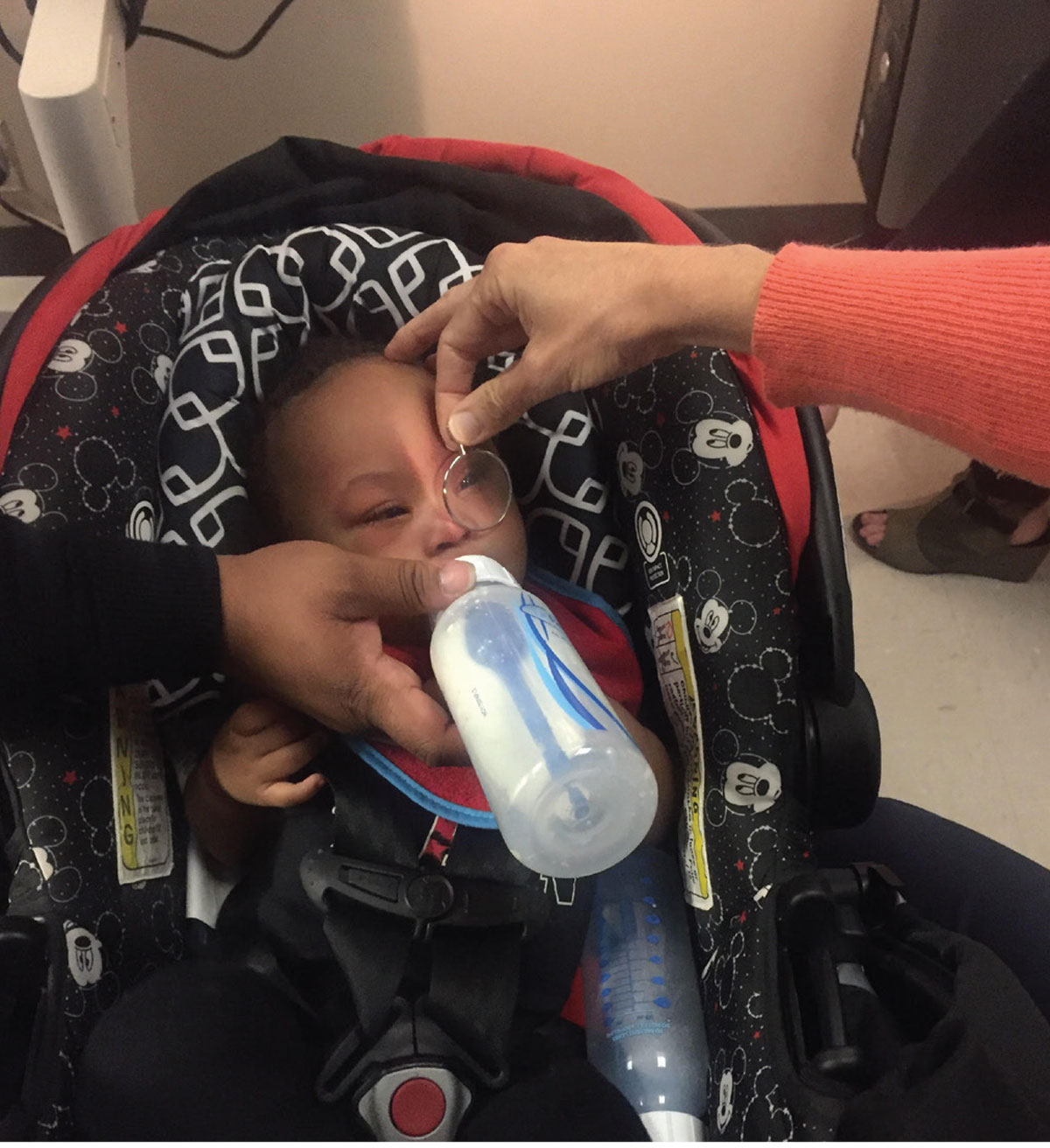

A parent keeps a young patient still by feeding them a bottle during an eye exam. |

We do respect when parents feel dilation is not the best option for their child after they have heard all of the relevant reasons for our suggesting it. For these patients, I have frequent follow-ups and make every effort to obtain a non-dilated view of the optic nerve at their initial visit. I would rather be managing patients in my office than have them walk away and possibly not be cared for at all. Parents typically respond well to this, and when I reach a level of concern about prescribing that I bring up dilation again, it is better received. I recommend dilating your pediatric patients whenever possible.

Effective Communication

The challenge of a pediatric exam comes from obtaining the above data in a non-traditional way. The same goes for communication with our pediatric patients during their exams and after when discussing the outcomes and the future of their children’s ophthalmic care. During any examination, technicians, doctors, patients and parents benefit from extensive description of what is going to happen, what is happening and what results we get from each exam element.

We find metaphors very helpful when communicating with both the patient and parent. I follow my colleague’s lead, as he has his metaphors very finely tuned, so a few that I cannot take credit for are below:

Keeping Kids EngagedCooperation by the patient and trust by the parent are improved when you keep discussion open throughout. Below are a few “scripts” that I find give patients and parents an idea of the next steps without alienating myself or my process. This includes giving optometry instruments fun names which can keep kids engaged and asking them questions about different objects in the room. These can be adjusted to your patient’s age, as nine-year-olds may be offended if you ask them to sing their ABCs. “I am going to use this spoon (cover paddle) and I will cover up each eye; you just get to sit and chat with me about the silly sticker on my mask—who is that? What about that airplane across the room—how many windows does it have?” “You have already done so much hard work! We only have three steps left and then you’re all done. We will use our wiggle flashlight (retinoscope), my crazy hat (BIO) and the bicycle (slit lamp, which has handlebars).” “Can you tell me what secret color is at the top of my spinning light?” “Is your mom making a silly face behind me?” |

Amblyopia: “Right now, Johnny’s right eye has Blu-ray quality vision. Because of his difference in prescription in the left eye, that eye has VHS quality vision, but we have a lot of tools to help us upgrade so that both eyes see especially well.”

Contact lenses: “Glasses are like a T-shirt; contacts are like a tuxedo. You have to take extra special care and a little more time at the beginning and end of the day to clean and take care of your contact lenses.”

Compliance: “The first few days you may not like these glasses; you may think that we didn’t get things right this time! But you gave me really good attention and I feel good about the prescription. Sometimes I like to call them ‘breakfast glasses’ because if we have them on for breakfast, we are more likely to wear them all day. It’s okay if you need to build-up wear over the week, too.”

|

|

A pediatric patient has a toy to keep her engaged during her exam. |

Follow-up: “You’ve got special eyeballs, they’re very interesting. Because of your special eyeballs, we are going to be good friends.” I then set the expectation for how often I plan to see the patient. For example, I may say every three to four months, only dilating annually unless needed otherwise.

Keeping open communication by talking throughout the exam, even if it is a one-sided conversation, can calm your nerves as well as the patient’s. If you are able to connect with your patient, the exam will be smoother and parents will often feel much more confident in your exam results.

I also like to inform parents and patients that dilation may last longer in children than they have experienced from their adult exams. If the patient has noted that near has blur, I reassure them with, “I know your hands look a little funny, the phone might, too. I promise that’s not forever, that will just be for today. You may enjoy far away activities more than up close activities today, and the nice people who check you out will have some groovy sunglasses for you.”

Our office sees patients of all ages, but I like to think that the front desk does enjoy greeting our pediatric patients. Big smiles (behind masks) from them upon arrival and departure are the icing on the cake to patient and parent experiences in our office.

Dr. Galt practices pediatric optometry at The Eye Center of Northern Colorado. She fell in love with caring for the pediatric patient population while at the University of Houston College of Optometry and specialized through the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Optometry Pediatrics Residency program. She has no financial disclosures.