|

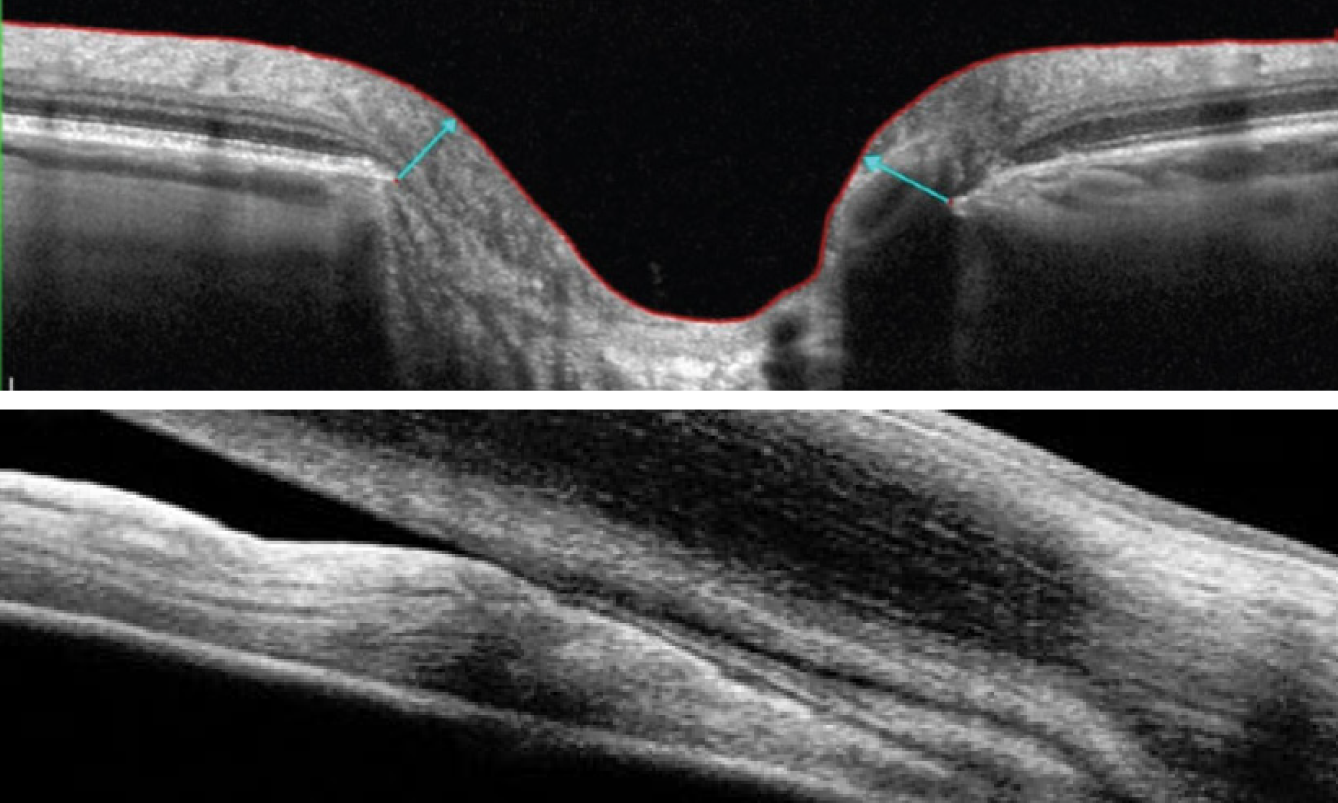

| Inferior field loss in PACG patients was found to have a total deviation difference of up to 3.2 dB worse than POAG patients at the same degree of RNFL loss. Researchers did not present information to confirm the mechanism of inferior field loss, but they encourage clinicians to not dismiss this as an artifact in the presence of preserved RNFL on OCT in a patient with PACG. Photo: James Fanelli, OD; Michael Cymbor, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Although the pathophysiological mechanisms of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) differ, researchers have not assessed their varying effects on optic nerve damage and visual field loss in a large-scale trial, only smaller studies that yielded inconsistent results. In new work published last week, researchers from Harvard and New York’s Mt. Sinai have provided a detailed characterization of structural and functional differences between POAG and PACG using a larger sample size than previous comparative studies.

Conducted at Mass General Brigham in Boston, this study examined 283 patients diagnosed with PACG and 4,110 experiencing POAG. Between 2015 and 2022, researchers used OCT scans and Humphrey visual fields to assess all subjects. Researchers discovered that more PACG patients were hyperopic, with a spherical equivalent of +0.29D, compared to -0.96D seen in the POAG group. They also found that PACG patients had a thicker global retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) on average than POAG (77 vs 71µm). Additionally, angle closure patients had a smaller cup volume (0.32 vs 0.4mm3), smaller cup-to-disc ratio (0.6 vs 0.7) and a larger rim area (1.07 vs 0.89mm3) than patients with POAG. However, inferior RNFL thinning was found to be more pronounced in POAG patients than PACG patients (82 vs 95µm).

This study used a large dataset to accurately differentiate POAG and PACG, but the researchers noted several limitations. They highlighted in their Journal of Glaucoma paper on the study that patients were identified using ICD-10 diagnosis codes, which can lead to misclassification and may have comprised the diagnostic accuracy of their data. They also failed to include lens status and axial length data, so the refractive status they reported may not reflect from the true difference between groups. Further limitations they disclosed: hyperopia was likely associated with rim artifacts, they did not assess for visual field learning effect, there was a significantly smaller sample size for the PACG group and most subjects were white, which limited their ability to assess differences between races and ethnicities.

Nevertheless, the team found the results to be illuminating. “We believe that our findings contribute to subtype-specific information that enhances the diagnosis and monitoring of these two glaucoma subtypes based on structural and functional differences,” stated the researchers in their paper. “Altogether, our findings support likely differences in the underlying pathophysiology of POAG and PACG.” They concluded that PACG patients had less structural damage than POAG patients despite similar degrees of functional loss.

Sun JA, Yuan M, Johnson G, et al. Comparison of structural and functional features on primary angle-closure and open-angle glaucomas. J Glaucoma. Nov. 28, 2023 [Epub ahead of print]. |