Q: I recently saw a patient with unilateral low-grade iritis that did not respond to steroid therapy. The patients iris color is lighter in one eye than in the other. What could this be, and how can I treat it?

A: Sounds like Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, says Daryl Mann, O.D., of Southeast Eye Specialists, a secondary care practice in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Like the patient described above, the classic patient with Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis has a very low grade chronic inflammation that responds poorly to steroids, Dr. Mann says.

The diagnosis is almost always made from the clinical signs. These include:

Anterior uveitis but without the acute symptoms (redness, pain, etc.) of other types of uveitis.

Small white keratic precipitates with stellate projections that connect one KP to another.

Mild cell and flare in the anterior chamber.

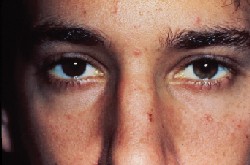

Depigmentation of iris color in the inflamed eye compared with the other (heterochromia).

The patient is also typically on the younger side, Dr. Mann says.

Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis accounts for about 2% to 11% of all cases of anterior uveitis.1 Although it doesnt share typical uveitic symptoms of redness and pain, Fuchs can lead to sequelae such as cataract and glaucomaperhaps as often as 20% of the time for glaucoma.2

Until now, the diagnosis has been a clinical one, Dr. Mann says.

But a recent study indicates that the etiology of Fuchs may be viral, specifically from the rubella virus.2 Thus, a laboratory test for rubella antibodies can now confirm a diagnosis, the researchers say.

The researchers stop short of recommending antiviral therapy for treatment, but it would be interesting to see whether patients respond to a course of, say, oral acyclovir, Dr. Mann says.

In any case, current therapy for the indolent inflammation of Fuchs usually consists of observation, he says, since patients are rarely symptomatic and steroid therapy is ineffective.

A: Sounds like Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, says Daryl Mann, O.D., of Southeast Eye Specialists, a secondary care practice in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Like the patient described above, the classic patient with Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis has a very low grade chronic inflammation that responds poorly to steroids, Dr. Mann says.

The diagnosis is almost always made from the clinical signs. These include:

Anterior uveitis but without the acute symptoms (redness, pain, etc.) of other types of uveitis.

Small white keratic precipitates with stellate projections that connect one KP to another.

Mild cell and flare in the anterior chamber.

Depigmentation of iris color in the inflamed eye compared with the other (heterochromia).

The patient is also typically on the younger side, Dr. Mann says.

Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis accounts for about 2% to 11% of all cases of anterior uveitis.1 Although it doesnt share typical uveitic symptoms of redness and pain, Fuchs can lead to sequelae such as cataract and glaucomaperhaps as often as 20% of the time for glaucoma.2

Until now, the diagnosis has been a clinical one, Dr. Mann says.

But a recent study indicates that the etiology of Fuchs may be viral, specifically from the rubella virus.2 Thus, a laboratory test for rubella antibodies can now confirm a diagnosis, the researchers say.

The researchers stop short of recommending antiviral therapy for treatment, but it would be interesting to see whether patients respond to a course of, say, oral acyclovir, Dr. Mann says.

In any case, current therapy for the indolent inflammation of Fuchs usually consists of observation, he says, since patients are rarely symptomatic and steroid therapy is ineffective.

|

| One distinctive characteristic of Fuch"s is that one eye is lighter in color thatn the other. Photo: Daryl Mann, O.D. |

Indeed, the recent study that ascribes a viral cause to Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis says, the discovery that [Fuchs] could be caused by the persistent rubella virus also offers a rationale for the empirical experience of many clinicians that the corticosteroid therapy used in [Fuchs] treatment is ineffective.2

With other types of uveitis, we tend to err on the side of overtreatment, Dr. Mann says. We dont want to undertreat, and then the patient comes back in a day or two and the eye is much worse.

But Fuchs doesnt work like other types of uveitis, he says. So the answer isnt to strengthen or lengthen steroid therapy. Simple observation is usually better.

The mistake you dont want to make is to treat patients so the eye looks better when theyre not really having symptoms, Dr. Mann says. Then you have them on high-dose steroids for a long period of time and they end up getting glaucoma or cataract as a result.

Q: Is Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis a disease I should comanange?

A: Because the decision-making process for Fuchs is relatively straightforward, many primary care optometrists will not request further consultation, Dr. Mann says. Theyll be able to manage the condition by themselves.

However, that doesnt mean there are no comanagement caveats. Specifically, if the patient is about to have cataract surgery, make sure the ophthalmic surgeon is aware of the patients condition.

| How to Identify Fuchs Heterochromic Iridocyclitis The classical diagnosis includes: Difference of iris color between the two eyes. Unilateral low grade anterior uveitis, but without acute symptoms such as pain or redness. White keratic precipitates. Mild cell and flare in the anterior chamber. Younger age. Is there a new way to diagnose? A recent study says that the condition has a viral etiology, so a lab study for rubella virus may be helpful.2 |

Oftentimes, your ophthalmic surgeon may not see the patient until theyre already dilated and therefore may not be aware that they have Fuchs, Dr. Mann says. So the surgeon may not take certain precautionary measures at the time of surgery that could avoid problems later.

For instance, the surgeon will likely select an acrylic intraocular lens rather than a silicone IOL for a patient with chronic uveitis or uveitic-induced cataract. This is because the acrylic material is more inert and less likely to carry the possibility of exacerbating inflammation.

The other major consideration in cataract surgery is that the pupil may not dilate as well because of the iris stromal atrophy that occurs with Fuchs, Dr. Mann says. So the surgeon may have to stretch the pupil to do proper capsulorhexis.

Another reason to make sure the surgeon knows about the condition concerns the location of the lens, he says. The surgeon should try to get the IOL implant within the bag and not within the sulcus, which could cause further aggravation if theres already some underlying propensity to have inflammation in the eye.

In the postoperative period, these patients may require more aggressive anti-inflammatory treatment, Dr. Mann says. Steroid eyedrops might be instilled every two hours for the first few days following surgery, for example, rather than the usual q.i.d. dosing. Likewise, the patient may require more follow up at your office for the initial few weeks following cataract surgery.

For instance, the surgeon will likely select an acrylic intraocular lens rather than a silicone IOL for a patient with chronic uveitis or uveitic-induced cataract. This is because the acrylic material is more inert and less likely to carry the possibility of exacerbating inflammation.

The other major consideration in cataract surgery is that the pupil may not dilate as well because of the iris stromal atrophy that occurs with Fuchs, Dr. Mann says. So the surgeon may have to stretch the pupil to do proper capsulorhexis.

Another reason to make sure the surgeon knows about the condition concerns the location of the lens, he says. The surgeon should try to get the IOL implant within the bag and not within the sulcus, which could cause further aggravation if theres already some underlying propensity to have inflammation in the eye.

In the postoperative period, these patients may require more aggressive anti-inflammatory treatment, Dr. Mann says. Steroid eyedrops might be instilled every two hours for the first few days following surgery, for example, rather than the usual q.i.d. dosing. Likewise, the patient may require more follow up at your office for the initial few weeks following cataract surgery.

| Ask Dr. Ajamian . . . Do you have a comanagement question or conundrum? If so, ask Dr. Ajamian. Send your question c/o jmurphy@jobson.com, or fax it to (610) 492-1031. |

- Tran VT, Auer C, Guex-Crosier Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of uveitis in Switzerland. Int Ophthalmol 1994-95;18(5):293-8.

- Quentin CD, Reiber H. Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis: rubella virus antibodies and genome in aqueous humor. Am J Ophthalmol 2004 Jul;138(1):46-54.

Vol. No: 141:11Issue:

11/15/04