|

A 76-year-old Caucasian female with moderately advanced open-angel glaucoma, OD>OS was initially seen in 2007, at which point she was undiagnosed. At that visit, her optic nerve appearances warranted further evaluation, which confirmed she was a glaucoma suspect without frank structural and functional glaucomatous damage.

In 2012, I noted structural changes to both optic nerves, OD>OS, that showed circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning OU and affected the neuroretinal rims.

After a trial period of glaucoma medications, we settled on a prostaglandin analog dosed at one drop OU HS. The patient remained on that regimen until 2017, at which time she was switched to Zioptan (tafluprost, Merck) OU HS for toxicity-related ocular surface issues.

The patient presented most recently in February 2021. She reported good compliance with the Zioptan and no resultant irritation. Her other medications included amlodipine, ibersartan, simvastatin and over-the-counter supplements. She is allergic to sulfa medications.

The patient’s entering visual acuities were 20/25- OD and 20/30- OS. Her last refraction was approximately nine months earlier, which yielded similar acuities. Her pupils were equally round and reactive to light and accommodation, with no afferent pupillary defect. Her extraocular muscles were full OU.

Slit lamp examination of the anterior segments was essentially normal. There were bilateral (mild) Salzmann’s nodules off the visual axis OU. Her angles were open OU. Her crystalline lenses were characterized by mild/moderate nuclear sclerosis and cortical spoking to a degree consistent with her visual acuities.

To obtain quality HRT-3 (Heidelberg) and OCT images, the patient was dilated in the usual fashion. Her cup-to-disc ratios were 0.75/0.80 OD and 0.65/0.70 OS. The nerve appearances were consistent with her previous visits over the past few years. The neuroretinal rim OD was thinnest in the superior temporal sector; whereas, the rim OS was thinnest in the inferior temporal sector.

Both macular evaluations were consistent with normal age-related changes centrally and characterized by mild retinal pigment epithelium granulation. There was a small epiretinal membrane along the superior arcade OS, not involving the foveal avascular zone. Her peripheral retinal evaluations at previous visits were normal.

The patient’s average intraocular pressures on Zioptan were 15mm Hg OD and OS. Central corneal thicknesses were 553μm OD and 565μm OS. Applanation tensions were 13mm Hg OD and 15mm Hg OS at 10:30 in the morning.

|

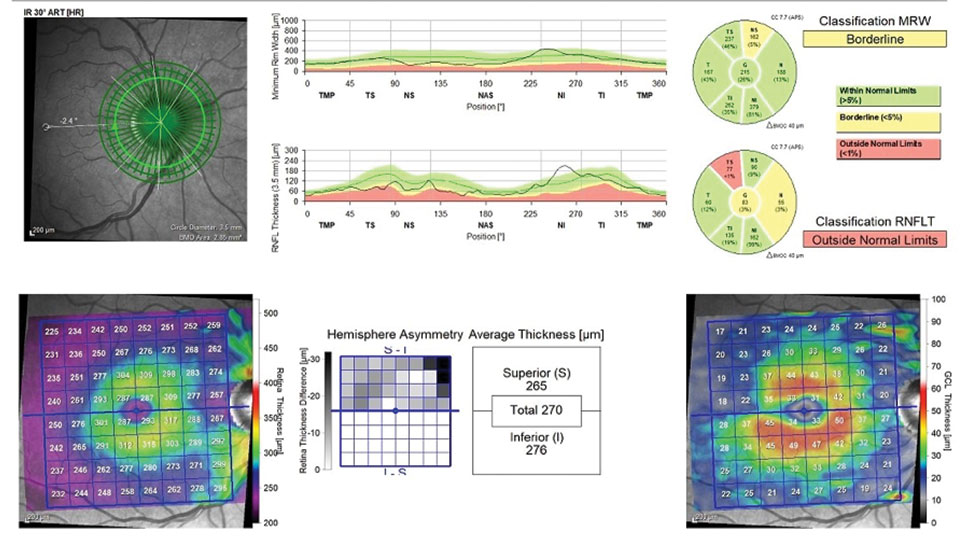

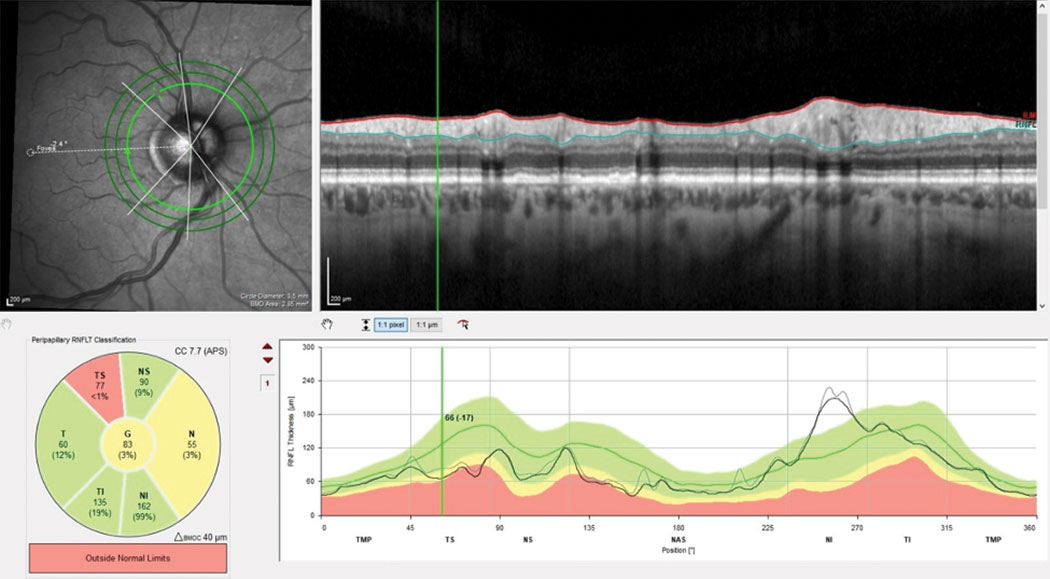

Here’s an overview of the three areas to observe when monitoring for disease progression: the neuroretinal rim, circumpapillary RNFL and macular region. Existing damage in this case can be readily seen in both the macular ganglion cell layer and the superior temporal RNFL. Click image to enlarge. |

|

| Here’s an overview of the three areas to observe when monitoring for disease progression: the neuroretinal rim, circumpapillary RNFL and macular region. Existing damage in this case can be readily seen in both the macular ganglion cell layer and the superior temporal RNFL. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussions

Periodic follow-ups for glaucoma patients are necessary to identify a variety of problems, with the most important being progression. Stability, or lack thereof, is determined by different testing methodologies, primarily by evaluating structural and functional indices. As we see glaucoma patients over the course of several years, it becomes somewhat easier to determine stability, as we now have multiple points of comparison. Aberrations or declines in structural or functional stability become readily evident with the accumulation of data points. Also with time, the protocols we follow for glaucoma management become almost second nature in stable patients.

Therein lies a caution: just because a glaucoma patient has remained stable for many years doesn’t mean they will always be stable. While gross changes or deterioration are easily detectable, subtle changes can be overlooked if we become complacent. On the other hand is the difficulty in determining progression vs. inter-testing variability. This is especially true in evaluating OCT findings that are measured in microns. While OCT technology has revolutionized glaucoma care, it can be challenging to detect early, subtle progression.

OCT instruments offer a plethora of information, much of which cannot fit in a simple 8.5x11 inch printout. It is helpful for me to have access to all the information obtained when a patient is scanned. Namely, it allows me to evaluate all areas where there may be progression. I have access to a progression analysis tool for OCT scans that not only plots progression in the RNFL and the neuroretinal rim, but also in each sector of both areas.

It is incumbent on us to know the nuances and limits of our imaging technologies, both what they tell us and what they don’t. Understanding each particular technology will help you decipher results from instrument to instrument and from test to test.

|

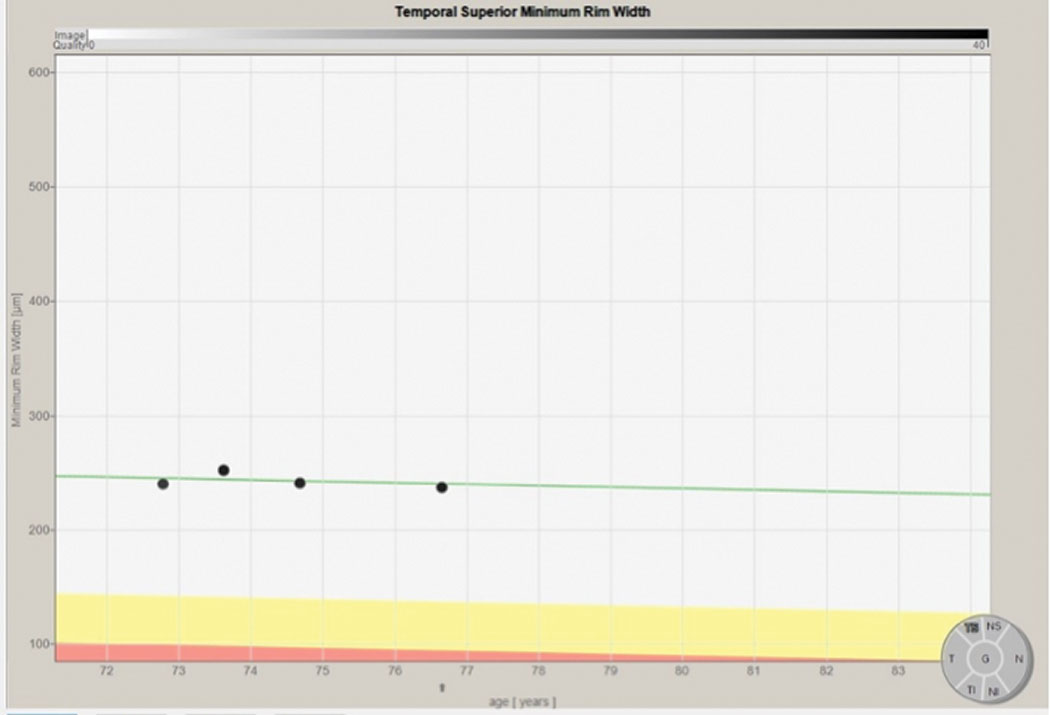

Progression analysis of the superior temporal sector of the neuroretinal rim over four scans spanning four years. The progression follows the expected gradual decline over time as noted by the green line. This indicates a normal situation and not significant glaucoma progression. Click image to enlarge. |

In this particular patient, previous visual field studies remained stable, with bilateral arcuate defects and nasal step formation. Her most recent visit aimed to determine structural stability. Along these lines, we need to keep a couple of points in mind. First, we must identify exactly where the disease has manifested. In early conversion or early disease, the damage may be isolated to one of three areas: the macular ganglion cell layer, circumpapillary RNFL or neuroretinal rim; whereas in advanced disease, damage can be seen in all three locations. The inferior temporal and superior temporal sectors of the neuroretinal rim and RNFL are typically affected first.

Next, we must remember how each patient first converted from a glaucoma suspect to a frank glaucoma patient. You may not know this information, especially if you inherited a long-standing glaucoma patient from a different provider. But a good rule of thumb to keep in mind is that wherever or however the initial signs of damage manifested, progression is likely to be seen in the same location or manner.

Which brings us back to this particular case. This patient initially converted to glaucoma as evidenced by changes in her neuroretinal rim (as imaged by the HRT-3) and the perioptic RNFL (as imaged by OCT). In her right eye, the initial changes were seen in the superior temporal sectors of each. I pay particularly close attention to the areas that were first compromised, despite the fact that progression can occur anywhere.

|

|

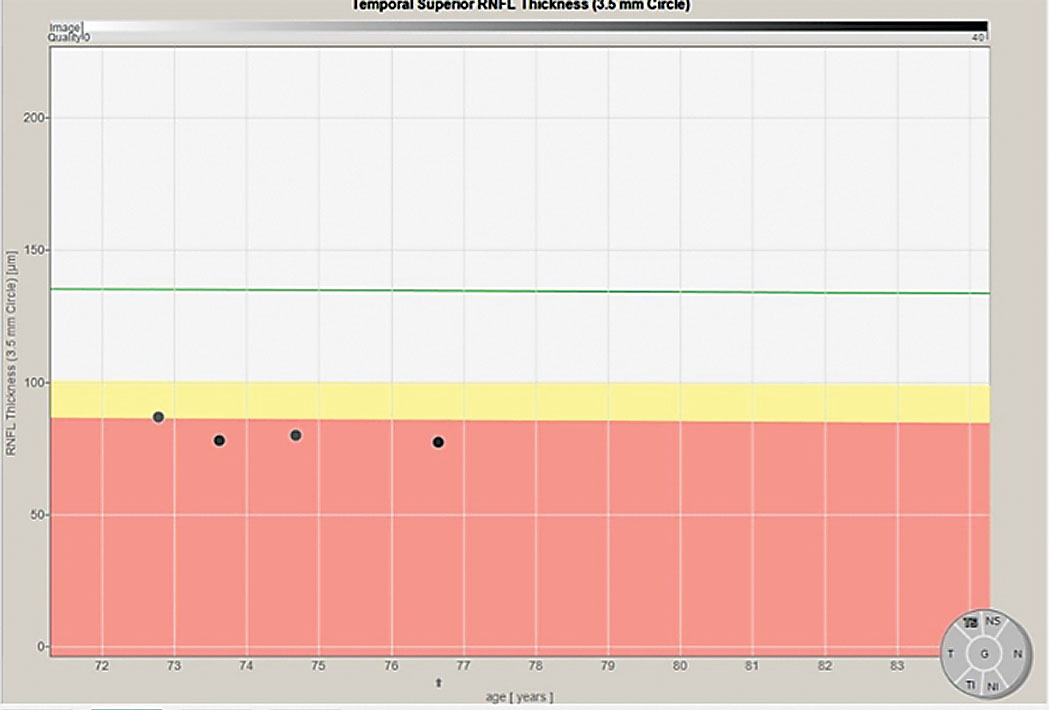

Progression analysis of the superior temporal sector of the RNFL using a 3.5mm scan, showing a subtle decline over a four-year period. This is suggestive of subtle progression. Click image to enlarge. |

So, is the glaucoma worsening in this case? It certainly appears so. If we glossed over the case findings, the patient’s subtle progression may have easily been missed. After all, what’s 17µm? Well, it’s 17µm that are no longer there. It’s not going to get better, only worse.

Now we must decide what to do with this information. Is that enough of a change to warrant an adjustment in therapy? Or should we reassess again in a few months? That is where clinical decision-making comes into play. Our technology may help guide us, but the decision is ultimately up to you. Missing the details and doing nothing, however, is not an option.

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heidelberg Engineering and Glaukos.