|

It all began with an optometry resident treating a 34-year-old woman for a painful swelling of her eyelid of four days’ duration. The pain had been increasing, forcing her to seek treatment. She had a small, internal focal swelling of her right upper eyelid, which was painful to palpation. The patient reported no trauma, use of new cosmetics or other products and didn’t recall being bitten by any insect. She was not ill and had no fever. After a comprehensive analysis, a resident correctly diagnosed a hordeolum and after educating the patient, had recommended hot, moist compresses and digital massage along with over the counter analgesics. After dismissing the happy patient, the resident shared the case and asked the opinions of several colleagues. Much to her surprise, each person had a different approach to treating patients with hordeola and each assured her that their approach “worked every time,” leaving the young doctor more confused.

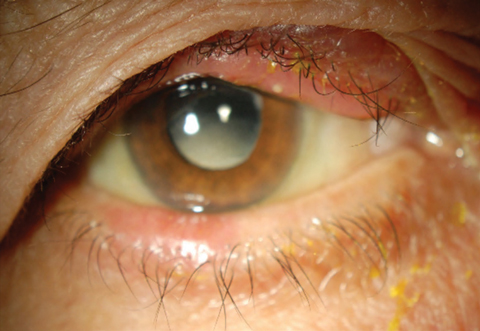

Hordeola are commonly encountered in clinical practice, and many clinicians have their own personal approach to managing this rather benign condition. A patient with a hordeolum will present with an acutely swollen and edematous upper or lower eyelid. Visual function will be normal, unless the swelling is so profound that it induces a mechanical ptosis or astigmatism. There may be an associated inflammation of the conjunctiva with possible mucopurulent discharge from the glands at the margin of the eyelid. The eyelid will be painful to palpation, sometimes extremely so. There may be an associated pustular pimple-like lesion at the epidermis or, more commonly, at the lid margin. Often, patients will present with a significant blepharitis concurrently. Hordeolum is one of the most common acquired lid lesions in children.1

|

| This patient’s swollen eyelid conceals a hordeolum, a common condition caused by a bacterial infection of the sebaceous glands. Click image to enlarge. |

Development

The sebaceous glands of the lids, the meibomian glands and glands of Zeis are the sites of origin of hordeola. Twenty to 30 meibomian glands are located in the upper lid and 10 to 20 in the lower lid and in the tarsal plate. Unlike the meibomian glands, the glands of Zeis are associated with the eyelash follicles. These glands produce the superficial lipid layer of tears.1

A hordeolum represents a bacterial infection of these glands of the eyelid with subsequent abscess formation. This will be associated with a tender, inflamed swelling at the lid margin, often pointing anteriorly through the skin. If the deeper glands are involved, the hordeolum is considered internal and is less well circumscribed in appearance. In these cases, you will see more diffuse swelling of the tarsus. The lesion may enlarge and discharge either through the tarsal conjunctiva or through the skin. The literature shows cases of multiple recurrent hordeola associated with selective IgM deficiency.2 Studies also show abnormal triglyceride fatty acid composition with chronic blepharitis associated with hordeola.3

Progression

The most commonly encountered organisms in hordeola are Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermis.4 Acute and chronic inflammation associated with hordeola may result in a hard retention cyst known as a chalazion, especially if it is improperly treated. Spread of infection to neighboring glands or other lid tissue anterior to the tarsal plate may lead to the formation of a preseptal cellulitis. While uncommon, hordeola can produce ocular surface disruption as a thickened lid rubs against the cornea and conjunctiva during blinking.4

|

| Treating a hordeolum, such as the one seen in this patient’s lower lid, includes using hot compresses, digital massage, topical antibiotics and ointments. |

Treatment

So, what are the options for treating an acute, painful hordeolum? First, remember that the infection is generally self-limiting and will often resolve within a week or two with spontaneous drainage of the abscess.1 Traditionally, the most common treatment involves the use of hot compresses with digital massage along with topical antibiotic solutions and ointments. Some advocate for oral antibiotics instead of topical treatment due to better absorption with subsequently higher therapeutic concentrations. Incision and curettage may also be helpful.

In a survey study involving 501 ophthalmologists, warm compress usage was employed by 92% of respondents.6 Additionally, combined topical and oral antibiotics were typically used.6 Only 2.4% of respondents used oral antibiotics alone, and 4.2% used no oral antibiotics.6 Incision and curettage was performed only in cases with a flocculated mass, larger lesions or if requested by patients. First choice antibiotics were a combination of topical neomycin, polymyxin and gramicidin eye drop, chloramphenicol eye ointment and oral dicloxacillin.6

Clearly, doctors have numerous approaches to handling this common infection, likely with varying success. When there is debate about best treatment and practices, it is always best to look at evidence-based medicine. Randomized, controlled clinical comparative trials give the best evidence on how to manage patients when there are numerous options and speculations. Unfortunately, hordeolum, though common, is considered benign and self-limiting and, as such, has garnered little in the way of clinical research. Reviews of the best available literature did not find any evidence for or against the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions for the treatment of an internal hordeolum.7 The few references specific to treating acute internal hordeola were reports of interventional case series, case studies or other types of observational study designs and were published more than 20 years ago.7

It is our feeling that topical antibiosis offers very little therapeutic benefit, since this mode likely does not offer sufficient intratissue concentrations of antibiotics to be therapeutic. However, topical antibiotics are prudent if there is significant concomitant blepharitis. We believe that oral antibiotic therapy is necessary to optimally treat hordeola. If the hordeolum is external and there is a pimple formed, then the lesion can be lanced and drained (anesthetic is usually unnecessary), or nearby lashes can be epilated to enhance drainage. Digital expression of purulent material in office will expedite healing, but is not absolutely necessary. Antibiotic therapy could include dicloxacillin 250mg PO Q6h; erythromycin 250mg PO QID; or amoxicillin 500mg PO TID for 10 days. Cephalexin 500mg BID for seven to 10 days is also an excellent, economical choice. Cold compresses will help to suppress inflammation and pain, while warm compresses will enhance pointing and drainage.

Clearly, optometrists have several acceptable methods to manage patients with hordeola. Each probably has varying degrees of success and therapies can be patient specific.

In our resident’s case, she walked away still confused with yet another opinion. But we assured her that our approach “works every time.”

1. Lederman C, Millier M. Hordeola and chalazia. Pediatrics in review 1999; 20(8):283-4. |