|

A long-standing glaucoma patient presented to the office for her regularly scheduled follow-up visit. She is 80 years old and has been a patient of the practice for 18 years.

Diagnostic Data

At this patients initial visit in 1987, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25- O.U. through a highly myopic refraction (approximately -10.00D O.U.). Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation with no afferent papillary defect. Her anterior segments were unremarkable. Applanation tensions were 15mm Hg O.D. and 16mm Hg O.S.

On dilated fundus examination, her lenses were clear in both eyes. Both posterior poles demonstrated moderate myopic stretching, foveolar reflexes were absent, and the macular picture was consistent with her 20/25 bilateral acuity. Optic nerve evaluations demonstrated cup-to-disc ratios of 0.65 x 0.70 O.D. and 0.75 x 0.80 O.S., with normal size nerves.

Her systemic medications at that time were only OTC allergy medications. She reported no allergies to medications. Repeat pressure readings were obtained, and two threshold visual fields were performed over the next month. Fields demonstrated rather mild paracentral areas of depression O.U.

Management

At that time, we diagnosed her with normal-tension glaucoma, and prescribed Timoptic 0.5% (timolol maleate, Merck) b.i.d. O.U. Post-treatment IOPs averaged 12mm Hg O.D. and O.S. She tolerated the medication well for several years, and her visual fields, optic nerves and IOPs remained stable.

Beginning in the late 1990s, however, I noted subtle changes in her optic nerves, as the advent of high quality stereo digital imaging of the optic nerves became more sensitive to such changes. Over the next several years, optic nerve damage progressed despite aggressive medical therapy and argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT). She developed cataracts that progressed slowly over the past five years.

By 2003, visual acuity had dropped to 20/50 O.D. and 20/80 O.S. The reduction in acuity was due to both the progression of the cataracts and relatively mild dry age-related macular degeneration. Threshold fields showed dense above and below arcuate scotomas O.U., not involving fixation. Optic nerve cupping progressed to 0.90 x 0.90 O.D. and O.S. The patient underwent two sessions of ALT in each eye.

|

|

The patients left eye in 2003. Note the advanced glaucomatous neuroretinal rim loss, vascular attenuation and peripapillary atrophy associated with her advanced disease. |

Systemic medications included Toprol XL (metoprolol, AstraZeneca), Premarin (conjugated estrogens, Wyeth), amiodarone, Coumadin (warfarin, Bristol-Myers Squibb) and Xanax (alprazolam, Pfizer). The amiodarone was added in late 2003 to assist in controlling a progressively worsening atrial fibrillation.

Unfortunately, the glaucomatous optic neuropathy continued to progress despite good compliance with her medications, and the patient ultimately underwent bilateral trabeculectomies with mitomycin-C in 2004. Her IOP following the trabeculectomy in the right eye averaged 8-10mm Hg unmedicated. The left eye was then plagued with chronic hypotony, until a bleb revision was performed about five months after the original trabeculectomy. A cataract extraction was performed during the same surgery. Fluorescein angiography did not demonstrate hypotonous maculopathy; both fundi were characterized by dry AMD changes.

|

|

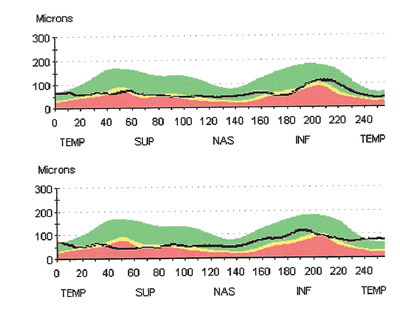

TSNIT images from OCT scan of perioptic nerve fiber layer (O.D. top, O.S. bottom). Note the loss of nerve fiber layer thickness and lack of typical double hump pattern. |

Discussion

This case brings up one undeniable fact about glaucoma: For some patients, despite aggressive therapy, vision loss progresses and results in severe visual impairment. The more you treat glaucoma patients, and especially the longer you treat the disease, the more patients like this you will undoubtedly see. And it is important that you feel confident in guiding them through the subsequent times should visual impairment be the end result.

When I finished optometry school, one of the common mantras went something like this: Dont be the last one to see a patient before he or she goes blind. I have heard various iterations of the same comment over the years. This can be taken in several ways. But this does not mean that optometrists should take a subordinate approach to managing patients, such as the patient in this case.

Certainly, it is imperative that we offer our patients the best care possible. And in cases such as these, that will necessarily involve the services of tertiary care specialists to provide those services that we cannot provide. But that does not mean that we should turn the entire care of the patient over to the specialist. While it may in fact be easier in many respects to release the patient to another practitioners care, it is well within the realm of optometry to handle the last seeing days of our patients. Its just something that many of us are not used to doing. Ive heard some optometrists say they chose the profession, in part, because they wouldnt have to deliver such bad news.

No longer. As the profession of optometry progresses and we, as practicing clinicians, continue to see more infirm and older patients, we will have to at least become more familiar with delivering the bad news. How is that done? There is no single answer. But the care of these patients should be compassionate. And optometrists, on the whole, are compassionate people. Who better to care for this patient of 18 years than the one eye-care provider whom she has seen more frequently than any other? In this patients case, we continue to discuss her worsening condition and she has, over time, come to realize the implications.

Glaucoma is an optometric disease. It can be readily managed by optometrists, even up to the end. If you are not comfortable managing glaucoma, then you shouldnt. That is a prudent decision. But please consider sending your glaucoma patients to a competent, fellow optometrist, who will certainly care for that patient compassionately. They do not always need to be sent to an ophthalmologist.

After reassessing this patients overall health status, it is clear that certain systemic conditions are at least contributing to her progressive vision loss, particularly her occlusive cardiovascular disease and dysrythmia. Continued management of these conditions by her cardiologist are important in her overall health. In the interim, I will continue to see her regularly and hold her hand through the rough times. But I will also keep my eyes open for anything that may offer her further help.