|

A couple presented to our clinic with concerns about their 23-month-old who, they say, was “cross-eyed since birth.” They also had some concern about his ability to see at distance. The child was delivered full-term with normal growth and development. He had no pertinent medical history. Family history was reported as unremarkable.

Upon exam, the child was able to fixate and follow with each eye. His pupils were equal, round and reactive to light, without afferent defect. Confrontation visual fields appeared full but with poor cooperation. Extraocular motility testing was full; we observed an esotropia. Anterior segments of both eyes were unremarkable. The patient was dilated and a limited fundus exam was performed, but based on the findings, we felt an exam under anesthesia (EUA) was warranted.

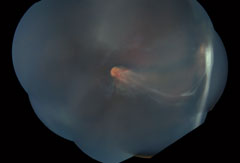

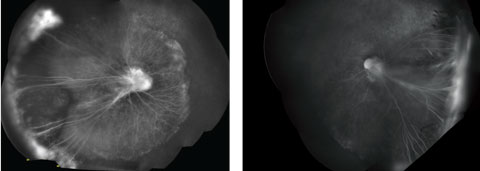

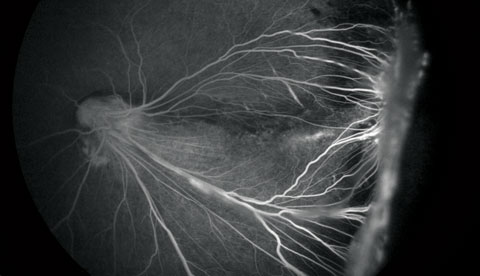

During the EUA, intraocular pressures (IOP) by Tono-pen (Reichert) measured 10mm Hg OD and 9mm Hg OS. Fundus exam, indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression and fluorescein angiography (FA) were performed. Fundus images (Figure 1) and FA images (Figures 2 and 3) were obtained.

|  |

| Fig. 1. These widefield montage fundus photos show the right eye (at left) and left eye at initial presentation. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. What is the likely diagnosis?

a. Retinopathy of prematurity.

b. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.

c. Coats’ disease.

d. Toxocara canis infection.

2. What does the FA reveal?

a. Avascular tissue.

b. Temporal dragging of vessels.

c. Both a and b.

d. This is a normal FA.

3. What is the inheritance pattern of this condition?

a. Autosomal dominant.

b. Autosomal recessive.

c. X-linked recessive.

d. All of the above are possible.

4. What other testing is indicated in the management of this patient?

a. Genetic testing of patient and family members.

b. Visual field testing.

c. MRI of brain and orbits.

d. No additional testing.

For answers, see below.

Discussion

The EUA revealed a large retinal fold involving the macula of both eyes with temporal dragging of the vessels. In the right eye, we observed an abnormal vascularity and significant areas of avascular tissue, which was highlighted by the FA. We saw no retinal detachment. Exam of the left eye revealed some vitreoretinal traction, especially towards the inferotemporal periphery, but we observed no tractional retinal detachment. Peripheral neovascularization was evident on both clinical exam and FA. Based on the clinical presentation, a diagnosis of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) was made. This was later confirmed by genetic testing. The patient was treated with peripheral laser 360 degrees in both eyes.

|

| Fig. 2. Do these montage FA images of the patient’s right eye (at left) and left eye, taken under anesthesia, point to a diagnosis? |

FEVR is, as its name suggests, familial and can be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked recessive pattern.1-3 It is caused by mutations in FZD4, LRP5, TSPAN12 and NDP genes, which impact the wingless/integrated (Wnt) receptor signaling pathway.3 Disruption of this pathway leads to abnormalities of vascular growth in the peripheral retina.2,3

It is typically bilateral, but asymmetric, with varying degrees of progression over the individual’s lifetime. Age of onset varies, and visual outcome can be strongly influenced by this factor. Patients with onset before age three have a more guarded long-term prognosis whereas those with later onset are more likely to have asymmetric presentation with deterioration of vision in one eye only.2-3 However, because FEVR is a lifelong disease, these patients are at risk even as adults.2 Ocular findings and useful vision typically remain stable if the patient does not have deterioration before age 20.2,4 Due to the variability and unpredictability of the disease course, patients with FEVR should be followed throughout their lifetime.

|

| Fig. 3. Close-up of the left eye FA at initial presentation. |

Clinical presentation can vary greatly. In mild variations, patients may experience peripheral vascular changes, such as peripheral avascular zone, vitreoretinal adhesions, arteriovenous anastomoses and a V-shaped area of retinochoroidal degeneration.4 Severe forms may present with neovascularization, subretinal and intraretinal hemorrhages and exudation.4 Neovascularization is a poor prognostic indicator and can lead to retinal folds, macular ectopia and tractional retinal detachment.2,4

Widefield FA has been crucial in helping to understand this disease, as well as helping to confirm the diagnosis. An abrupt cessation of the retinal capillary network in a scalloped edge posterior to fibrovascular proliferations can be made using FA.2,3,5 Patients can also show delayed transit filling on FA as well as delayed/patchy choroidal filling, bulbous vascular terminals, capillary dropout, venous/venous shunting and abnormal branching patterns.2,3,5

The staging of FEVR is similar to that of retinopathy of prematurity. The first two stages involve an avascular retinal periphery with or without extraretinal vascularization (stage 1 and 2, respectively).4 Stages three through five delineate levels of retinal detachment; stage 3 is subtotal without foveal involvement, stage 4 is subtotal with foveal involvement and stage 5 is a total detachment, open or closed funnel.4 Because there was neovascularization in the absence of retinal detachment, our patient was considered to have stage 2.

Treatment is based on the stage of the disease. Stage 1 does not require treatment and should be observed.4 Neovascularization (stage 2) responds well to laser ablation or cryotherapy.2,4 Eyes with retinal detachments (stages 3 through 5) require surgery, with earlier stages requiring scleral buckles and later stages ultimately needing vitrectomy.2,4

More recently, the efficacy of anti-VEGF intravitreal injections has been studied. In one study, these injections, as an in adjunct with laser, helped early stages achieve stabilization, but further investigation is needed.6

Our patient was followed every three months with EUA and received laser five more times in each eye. Subsequently, at the age of 2.5 years, a tractional retinal detachment developed in the left eye, and the patient underwent a pars plana vitrectomy/scleral buckle/membrane peel procedure. At the two month postoperative visit, his uncorrected vision, at near, was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/160 in the left eye. He continues to be monitored closely with EUA.

|

1. Criswick V, Schepens C. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968:578-94. |