A 62-year-old white male presented for a second opinion about the decreased vision in his left eye. He said that his vision loss occurred suddenly one year ago without pain and has not improved since then.

His ocular history was significant for borderline elevated intraocular pressure, for which he instilled Lumigan (bimatoprost, Allergan) O.U. at bedtime each night.

His medical history was positive for systemic hypertension, arthritis, diverticulitis and hypercholesterolemia. Medications included Norvasc (amlodipine besylate, Pfizer), lorazepam and Celebrex (celecoxib, Pfizer). He also took a multivitamin supplement.

Best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/15 O.D. and 20/100 O.S. Extraocular motility testing was normal, and pupils were equally round and reactive with no afferent pupillary defect. Confrontation visual field testing was full to careful finger counting O.U. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Intraocular pressure measured 14mm Hg O.D. and 15mm Hg O.S.

Dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed moderately large cups with good neural-retinal rim coloration and perfusion. The remainder of the dilated exam in that eye was unremarkable.

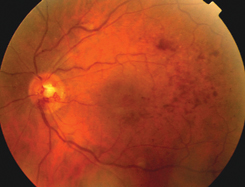

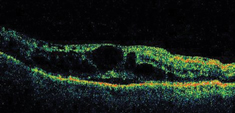

Dilated fundus examination of the left eye revealed the changes seen in figure 1. We ordered optical coherence tomography, or OCT (figure 2).

Take the Retina Quiz

1. Fundus photo of the left eye shows an unusual appearance of the optic nerve and scattered retinal hemorrhages in the midperiphery.

1. What are the changes seen on the left optic nerve?

a. Neovascularization of the disc.

b. Congenital ateriovenous malformation.

c. Optociliary shunt vessels.

d. Papillitis.

2. What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Prior central retinal vein occlusion.

b. Optic nerve sheath meningioma.

c. Advanced glaucoma.

d. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

3. What does the OCT reveal?

a. Choroidal neovascular membrane.

b. Retinal pigment epithelial detachment.

c. Cystoid macular edema.

d. Subretinal fluid.

4. What treatment has NOT been shown effective for this condition?

a. Voltaren (diclofenac, Novartis Ophthalmic) qid.

b. Photodynamic therapy.

c. Macular grid photocoagulation.

d. Intravitreal Kenalog (triamcinolone) injection.

5. How should we manage this patient?

a. Observation.

b. Laser photocoagulation.

c. MRI.

d. Intravitreal Kenalog injection.

For answers, click here.

Discussion

The anomalous dilated vessels on the optic nerve in the left eye represent optociliary shunt vessels. These can develop as a result of advanced glaucoma, optic nerve sheath meningioma or from an old central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). Optic nerve sheath meningioma is the most serious of these; hence you must rule that out. We did not consider the possibility of advanced glaucoma in this patient because the optic nerve did not appear glaucomatous.

Optic nerve sheath meningiomas are most prevalent in middle-aged females who present with painless, gradual vision loss. These patients may have disc swelling or pallor, an afferent pupillary defect and proptosis.

Our suspicion for optic nerve sheath meningioma was actually pretty low, given the other fundus changes we noted in this patient. These included scattered diffuse retinal hemorrhages and sheathing of the retinal vessels. These findings can also be seen in fundus photos. These changes, along with the shunt vessels and the patients history of hypertension, suggested the patient had an old CRVO.

CRVO is the second most common vision-threatening vascular disorder in patients past age 50, behind diabetic retinopathy in the United States. The etiology of CRVO can be attributed to atherosclerosis within the adjacent central retinal artery. This results in increased blood viscosity, damage to vascular endothelial cells or abnormal platelet formation. Due to his long history of hypertension, our patient probably had a combination of atherosclerosis and endothelial cell damage.

Clinical examination of an acute CRVO may reveal an afferent pupillary defect, neovascularization of the iris or angle, diffuse retinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants of the fundus, dilated and tortuous retinal veins, cotton-wool spots, disc edema and macular edema.

Old CRVOs may be more difficult to diagnose, as disc swelling and hemorrhages may resolve over time, resulting in a near-normal retinal appearance. The only remnants of an old CRVO may be optociliary shunt vessels and sheathing of the retinal vessels, as in our patient.

CRVO is classified as ischemic or nonischemic. Nonischemic CRVO generally presents with good to moderate vision, adequate retinal perfusion, few retinal hemorrhages, and cotton-wool spots; usually there is not a relative afferent pupillary defect. Scattered retinal hemorrhages will be present, but are usually less dense than what is seen in an ischemic CRVO. Patients who have nonischemic CRVO can have an excellent visual outcome or progress to the ischemic form.

Ischemic CRVO represents 20 to 25% of all CRVO cases.1 Patients who have the ischemic form will have marked vision loss (20/400 acuity or worse), greater than 10 disc diameters of nonperfusion on fluorescein angiography and positive afferent pupillary defect. Ischemic CRVO also has a higher incidence of neovascularization of the iris and angle, leading to neovascular glaucoma.1

2. These findings on OCT may explain the patients reduced visual acuity.

Although our patient did not undergo fluorescein angiography on the date of the examination, we assumed that he had a non-ischemic CRVO. We based our assumption on to the fact that our patient did not have an afferent pupillary defect, nor did he have neovascularization of the iris or angle.

The optociliary shunt vessels seen in our patient represent abnormal blood vessels on the optic nerve. These abnormal vessels redirect the blood from the retina to the choroid. They can occur in up to 50% of patients following CRVOusually 6.7 months after the initial onset of the CRVO.2

The presence of shunt vessels demonstrates good compensatory circulation, which greatly reduces the likelihood that the patient will develop neovascular complications.

Our patients reduced acuity in his left eye is from cystoid macular edema, as seen on OCT. Macular edema is a very common cause of visual reduction in CRVO patients.

To date, there has been no effective treatment for macular edema secondary to CRVO. The Central Vein Occlusion Study evaluated laser photocoagulation for macular edema, but found no benefit.3

More recently, however, intravitreal Kenalog injections have shown great promise for treating macular edema and improving visual recovery from other causes of retinal vascular disease, such as diabetic retinopathy and branch retinal vein occlusion.4 So, intravitreal Kenalog may be a possible treatment for macular edema from CRVO. Realize, however, that the potential side effects of intravitreal Kenalog include endophthalmitis, increased IOP and cataract formation.

We explained the diagnosis to our patient and discussed intravitreal Kenalog for treating his macular edema. The patient elected to have the injection, and his vision improved to 20/20 with resolution of the CME. However, he did develop chronic elevated IOP and eventually required glaucoma filtration surgery.

This months column was co-written by William Prunty, O.D., and Brian Cho, O.D. Both are optometry residents at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami.

1. Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB, Podhajsky P. Incidence of various types of retinal vein occlusion and their recurrence and demographic characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol 1994 Apr 15;117(4):429-41.

2. Fuller JJ, Mason JO 3rd, White MF Jr, et al. Retinochoroidal collateral veins protect against anterior segment neovascularization after central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 2003 Mar;121(3):332-6.

3. Evaluation of grid pattern photocoagulation for macular edema in central vein occlusion. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group M report. Ophthalmology 1995 Oct;102(10):1425-33.

4. Ip M, Kahana A, Altaweel M. Treatment of central retinal vein occlusion with triamcinolone acetonide: an optical coherence tomography study. Semin Ophthalmol 2003 Jun;18(2):67-73.