An 84-year-old white male presented and reported a film over his right eye for the past 10 days. He denied symptoms of pain or photophobia.

His records revealed that earlier in the year, another practitioner successfully treated him for a slowly resolving keratouveitis in his right eye secondary to herpes simplex virus (HSV). His systemic history was noncontributory, and he reported no known allergies.

Diagnostic Data

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/400 in his right eye and 20/20 in his left at distance and near. Exter-nal examination demonstrated normal motilities, fields, color vision and brightness sense. There was no afferent pupillary defect. The right eye was not injected with vesiculations of lid or facial skin. Retinoscopy uncovered an asymmetric reflex that was much worse in the right eye than in the left, but the subjective refraction demonstrated no changes to his +2.00D spectacle prescription. Slit lamp biomicroscopy was remarkable for mild seborrheic blepharitis in both eyes and 1+ injection of the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva in the right eye.

|

|

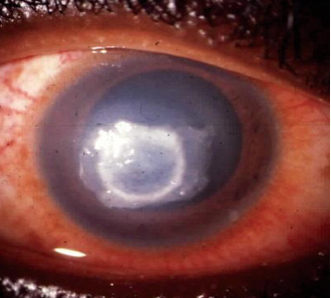

Clinical features of a neurotrophic ulcer include chronic, sterile ulceration with gray, thickened borders. |

The anterior chamber in the right eye had 2+ cells and flare, while the left anterior chamber was deep and quiet. We noted a well-positioned posterior chamber IOL in the patients right eye and an anterior chamber IOL in the left, with patent YAG capsulotomies in both eyes. Intraocular pressure measured 13mm Hg O.D. and 12mm Hg O.S.

Dilated fundus exam was normal, with quiet vitreous, nerves, and central and peripheral grounds. Cup-to-disc ratios measured 0.4x0.4, O.U. Disc color was normal, and neuroretinal rims were distinct.

Diagnosis

We initially diagnosed this patient with herpes simplex neurotrophic ulceration with resultant iritis.

Treatment and Follow-up

We initiated treatment with topical homatropine 5% b.i.d. to ensure that the patient remained comfortable and to stabilize the permeability of the iris blood vasculature. We also started a topical fluoroquinolone q.i.d. to protect the exposed cornea from infection. We decided to observe the behavior of the lesion before adding a topical anti-inflam-matory drug. We also chose not to prescribe topical antiviral therapy because an arborizing ulcer was not present and these agents may cause corneal toxicity. We told the patient to return for follow-up in two days.

The patient returned as scheduled but did not show any improvement. By exclusion, we revised our diagnosis to HSV keratouveitis with stromal involvement. We initiated therapy with Viroptic 1% (trifluridine, King Pharmaceuticals) q2h, discontinued the topical antibiotic, maintained the homatropine 5% b.i.d. and continued to withhold topical corticosteroids. We scheduled a follow-up appointment in three days.

At the patients follow-up appointment, he was in stable condition but did not show significant improvement. We instructed him to continue with his therapy and referred him to a corneal specialist for a second opinion.

|

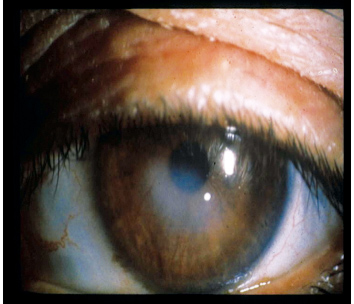

| Disciform stromal keratits is one manifestation of HSV in the eye. |

At this next visit, the patient was in stable condition. While the stromal edema decreased, the ulcers size and depth did not significantly improve. We now decided to initiate a topical corticosteroid (prednisolone acetate 1% t.i.d.). We scheduled follow-up visits for every week during the next month.

During this period, the patients condition slowly and steadily improved. His visual acuity was now 20/25 in his right eye. We titrated the cycloplegic, tapered and discontinued the topical corticosteroid and maintained the oral acyclovir to prevent recurrences. We scheduled a final follow-up visit in two weeks.

The patient returned one week prior to his scheduled appointment complaining of periorbital pain and a film over his right eye for the past two days. Visual acuity had decreased to 20/80 in his right eye. The clinical presentation appeared similar to the presentation at his initial visit, except that his epithelium was intact. We detected a severe anterior chamber reaction with plasmoid aqueous in his right eye. His current medications included oral acyclovir 400mg p.o. b.i.d., artificial tear drops and artificial tear ointment at bedtime.

We diagnosed the patient with recurrent HSV keratouveitis. This time, we immediately initiated an aggressive treatment regimen that included a topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1%) q1h, homatropine 5% b.i.d. and topical antiviral drops q.i.d. We instructed him to continue using the oral acyclovir, artificial tears and ointment.

Today, the patient continues to improve on this regimen. The corneal edema and anterior chamber reaction have again demonstrated full resolution, and visual acuity has improved to 20/20-. We continue to follow the patient regularly and anticipate continuing oral acyclovir and a topical cortico-steroid for a prolonged period with a slow taper to prevent another episode of rebound keratouveitis.

Discussion

HSV is one of the most common infectious agents.1-16 About 90% of the adult population is seropositive for HSV antibodies, indicating prior exposure or infection.1 Ocular herpes simplex is the leading infectious cause of corneal blindness in the United States, with 500,000 cases reported each year.2-4

After HSV infects cells, it travels by retrograde axoplasmic flow to the trigeminal ganglia, ciliary ganglia, mesocephalic nucleus of the brainstem and the sympathetic ganglia, where it enters a latent state.2 The virus remains in the ganglia until it is reactivated, causing recurrent infection. Risk factors for reactivation include stress, wind, sun exposure, fever, emotional stress, menses, surgery, immunocompromise and trauma.2-4

There are two strands of HSV: HSV-1, which is commonly acquired during childhood and is usually asymptomatic, and HSV-2, which is sexually transmitted.

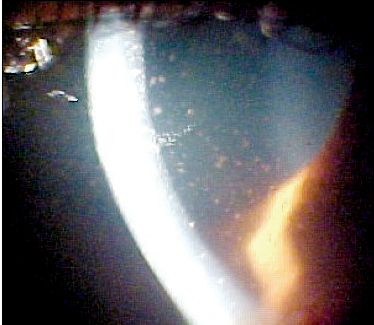

|

|

Keratic precipitates were found on the epithelium due to uveitis. |

Disciform stromal keratitis (DSK) is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the HSV-antigenic change of the surface membranes of stromal cells.2,3 A clinical feature of DSK is diffuse stromal edema, which is usually centrally located.1 The severity of edema varies among patients. Marked corneal anesthesia has been noted among patients with DSK.1,3,4 DSK is sometimes associated with Descemets folds and KPs.5 In severe cases, deep and superficial neovascularization may be present. Focal bullous keratopathy may also develop in severe presentations. Additionally, iritis is almost always present in moderate to severe cases of disciform stromal keratitis.2

HSV stromal disease accounts for 2% of initial episodes of ocular HSV and 20% to 48% of recurrent ocular HSV.6 Several studies have been performed to determine whether active viral infection or an immune response cause HSV stromal disease; most support an immune response.2,3,7,8

Treatment of DSK is controversial. Because DSK occurs as an immune response, some literature recommends using a corticosteroid to reduce stromal inflammation or edema.1-4,9,13,14 When corticosteroids are prescribed, an antiviral should be used concurrently to prevent reactivation of viral infection.1-4,9,13,14 The corticosteroid should be tapered over several weeks to months to prevent rebound.1,2,5 Other studies, however, state that corticosteroids are contraindicated because they can exacerbate viral infection.11

When choosing between topical and oral antiviral treatment, consider study results and medication side effects. Topical trifluridine is toxic to the cornea, so use this agent judiciously with an irregular epithelium or epithelial defect.1,3,11 Additionally, viruses may be resistant to oral acyclovir.12 One study showed that combined topical and oral acyclovir was not effective for treating stromal disease.12 Another study found that topical acyclovir with-out concomitant steroids is not an effective treatment.4

The Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) concluded that there was no clinically significant effect of oral acyclovir in patients with HSV stromal keratitis who received concomitant topical corticosteroids and trifluridine.10,13,14 HEDS also concluded that topical steroid treatment was significantly better than placebo at reducing persistence or progression of stromal inflammation and at shortening the duration of HSV stromal keratitis.9,13,14

Clinical features of a neurotrophic ulcer include chronic, sterile ulceration with gray, thickened borders formed by heaped-up epithelium.6,7 Here, the epithelium cannot move across or adhere to the damaged ulcer base.2 Early findings may be as subtle as an irregularity of the corneal surface or lack of normal corneal luster.6

Neurotrophic ulcers occur secondary to interactive adverse factors, including impaired corneal innervation, abnormal tear film stability and damaged basement membrane.2,6 The damaged basement membrane takes at least 12 to 15 weeks to repair itself, so the overlying epithelial defect heals slowly.2 A persistent neurotrophic ulcer eventually leads to stromal ulceration.6

Treatment of neurotrophic ulcers may include adding patching or soft bandage contact lenses and copious lubrication with non-preserved artificial tears and ointment to the current therapy to protect the damaged basement membrane.1-4 Tarsorrhaphy may be indicated for slow-healing or persistent ulcers.4

HSV uveitis is often accompanied by photophobia, posterior synechiae formation and occasionally secondary glaucoma.3,4,11 The clinical features of HSV uveitis may be associated with epithelial or stromal disease.

Whether HSV uveitis is due to hypersensitivity mechanisms or direct infection of the uveal tract by the virus is unclear.11 The presence of uveitis in addition to active keratitis may be due to reaction to the viral antigen in the iris or to the irritative effects of the keratitis.2

Treatment of uveitis that accompanies HSV includes cycloplegics, topical corticosteroids and topical or oral antiviral therapy.3 HEDS attempted to evaluate the effect of adding oral acyclovir to topical prednisolone sodium phosphate and trifluridine for treating HSV uveitis, but the trial was stopped because of slow recruitment.13,14

An estimated 40% of ocular herpes recurs within five years.2 HEDS evaluated the efficacy of using oral acyclovir (400mg b.i.d.) prophylactically to prevent recurrent ocular HSV disease. Some key findings:

The probability of a recurrence of any type of ocular HSV disease during the 12-month treatment period was 19% in the acyclovir group and 32% in the placebo group.13,14

Among patients with a history of stromal keratitis, the probability of recurrent stromal keratitis was 14% in the acyclovir group and 28% in the placebo group.13,14

The rate of HSV did not rebound in the six months after acyclovir was stopped.13,14

Long-term oral prophylaxis can reduce the rate of recurrent ocular HSV and is most important for patients who have a history of HSV stromal keratitis.13,14

Recent research has examined the effects of emotional and physical stress on recurrences of ocular HSV and prophylactic treatment to prevent recurrences.15 The virus occurred less frequently on the ocular surface in stress-induced mice treated with acyclovir than in those treated with placebo. However, acyclovir was not effective in preventing viral reactivation in the trigeminal ganglion.15

Another study evaluated the efficacy of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid, or ASA) on ocular shedding of HSV in mice. Fewer HSV-infected mice that were treated with intraperitoneal ASA showed infectious virus on the ocular surface and in the trigeminal ganglion 24 hours after reactivation compared with stressed mice treated with saline.16 Similar results were found in the mice that were treated prophylactically and therapeutically with oral ASA.16

In another study conducted on monkeys, the highly specific cycloxygenase inhibitor (COX-2) DFU (dimethyl fluorophenyl) was even more effective at reducing HSV-1 recurrences than ASA. This effect was revealed on the ocular surface and in the trigeminal ganglion.5,17

Ocular HSV is a very common condition that can manifest in many different forms. So, consider herpetic eye disease in your differential diagnosis when patients present with epithelial, stromal and endothelial disease as well as uveitis and retinitis. Proper treatment is critical, as incorrect treatment can lead to worsening of the disease.

Dr. Michelle Beachkofsky is a cornea and contact lens resident, and Dr. Mira Silbert Aumiller is adjunct faculty, Pennsylvania College of Optometry. Dr. Silbert Aumiller is also a staff optometrist at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Wilmington, Delaware. Dr. Andrew Gurwood is an associate professor, Pennsylvania College of Optometry, and the author of Review of Optometrys Diagnostic Quiz column.

1. Kanski JJ. Cornea. In: Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systemic Approach. 5th ed. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003:107-11.

2. Pavan-Langston D. Viral keratitis and conjunctivitis. In: Smolin G, Thoft RA, eds. The Cornea. 3rd ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984:183-99.

3. Dumestre DM. Herpes simplex. In: Marks ES, Adamczyk DT, Thomann KH, eds. Primary Eyecare in Systemic Disease. Norwalk, Conn.: Appleton and Lange, 1995:438-46.

4. Pepose JS, Leib DA, Stuart PM, Easty DL. Herpes simplex virus diseases: anterior segment of the eye. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, eds. Ocular Infection and Immunity. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996:905-26.

5. Kaufman HE. Your herpes virus. Audio-Digest Ophthalmology 2003 April 21;41(8).

6. Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea 1999 Mar;18(2):144-54.

7. Newell CK, Martin S, Sendele D, et al. Herpes simplex virus-induced stromal keratitis: role of T-lymphocyte subsets in immunopathology. J Virol 1989 Feb;63(2):769-75.

8. Pepose JS. Herpes simplex keratitis: role of viral infection versus immune response. Surv Ophthalmol 1991 Mar-Apr;35(5):345-51.

9. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study: a controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 1994;101(12):1883-95.

10. Barron BA, Gee L, Hauck WW. Herpetic Eye Disease Study: a controlled trial of oral acyclovir for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 1994;101(4):1871-82.

11. Friedlaender MH. Immunology of ocular infections. In: Allergy and Immunology of the Eye. Hagerstown: Harper and Row, 1979:123-30.

12. Sanitato JJ, Asbell PA, Varnell ED, et al. Acyclovir in the treatment of herpetic stromal disease. Am J Ophthalmol 1984 Nov;98(5):537-47.

13. Sudesh S, Laibson PR. The impact of the herpetic eye disease studies on the management of herpes simplex virus ocular infections. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1999 Aug;10(4):230-3.

14. Barron BA. the Herpetic Eye Disease Study. In: Kertes PJ, Conway MD. Clinical Trials in Ophthalmology. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1998:283-303.

15. Gebhardt BM, Kaufman HE, Hill JM. Effect of acyclovir on thermal stress-induced herpes virus reactivation. Curr Eye Res 2004 Aug-Sep;29(2-3):137-44.

16. Gebhardt BM, Varnell ED, Kaufman HE. Acetylsalicylic acid reduces viral shedding induced by thermal stress. Curr Eye Res 2004 Aug-Sep;29(2-3):119-125.

17. Kaufman HE. Can we prevent recurrences of herpes infections without antiviral drugs? The Weisenfeld Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002 May;43(5):1325-29.