A 42-year-old white female presented to our military medical centers optometry clinic for a routine exam. She had no visual complaints. She reported good visual acuity with her current spectacles but wanted an updated prescription because her current pair was about two years old.

She reported that her family and personal medical histories were unremarkable except for occasional headaches and seasonal allergies. She said she was not taking any medications and did not drink or smoke. Her ocular history was also unremarkable except for a white spot in her right eye, which she said many eye doctors had noted since it was discovered when she was about twelve years old. She reported that the spot drew attention during exams, but she could not recall a diagnosis being assigned to it.

A review of her general medical record uncovered documented eye exams in 1992, 1994, 1996 and 2000. Each provider documented an elevated white lesion in the posterior pole of the right eye, but as she mentioned, no specific diagnosis was given. Her record contained a Polaroid photo of the lesion that was taken in 1992. Civilian doctors performed other exams over the years, but we did not have reports from those exams.

Diagnostic Data

Her entering visual acuities were 20/20 in each eye with a prescription of 2.00-0.50x115 O.D. and 1.75-0.25x090 O.S. Her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/15 in each eye with manifest refraction of 2.25-0.50x115 and 2.25 sphere. Pupils, extraocular muscles and adnexa were normal in both eyes. The lids, conjunctivas, corneas, anterior chambers, irises and crystalline lenses were unremarkable under slit lamp examination. Intraocular pressure measured 13mm Hg O.D. and 11mm Hg O.S. with non-contact tonometry.

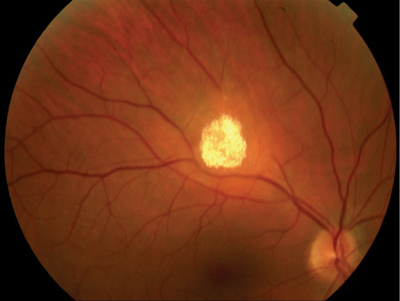

|

| 1. The dilated fundus exam revealed a raised white calcified mass near the superior arcade above the macula. |

|

|

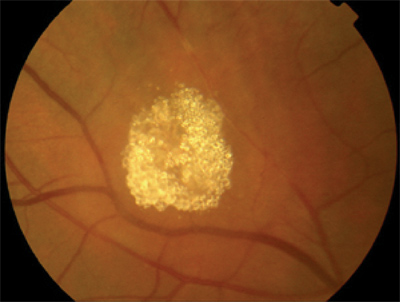

2. The lesion appeared to have a calcified granular composition. |

Diagnosis

We diagnosed this patient with solitary unilateral calcified retinal astrocytic hamartoma and bilateral compound myopic astigmatism.

Follow-up

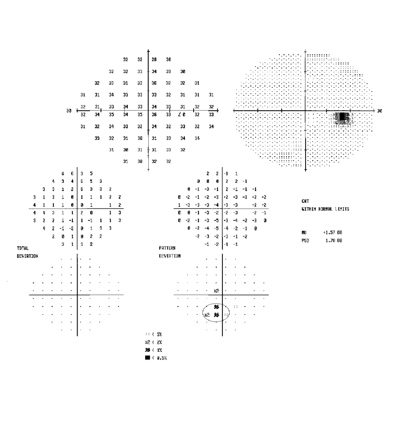

We asked this patient to return at another time for a visual field test. We performed a Humphrey central 30-2 threshold visual field test, which demonstrated a very mild relative defect corresponding to the lesion (figure 3).

|

|

3. A Humphrey visual field test demonstrated a very mild relative defect corresponding to the lesion. |

We obtained the report from the geneticist, which stated that DNA analysis confirmed that she possessed the DNA fragment deletion linked to DMD. This information was important because the literature does not report on a link between DMD and astrocytomas. Such an occurrence could be coincidental, or this could be the first report of a link between DMD and astrocytomas.

We provided our patient with a new prescription for her spectacles. We also informed her of the nature of her retinal lesion and told her that treatment of the lesion is not necessary. We examined her again 11 months later and there was no change in her ocular condition.

Discussion

Astrocytic hamartomas, or astrocytomas, are benign lesions of the retina or optic disc that originate within glial tissue normally present at the site.1 They are usually unilateral and solitary in patients with normal health. When astrocytomas are bilateral or multifocal, they are often associated with tuberous sclerosis (TS), a multisystem disorder characterized by mental retardation, epilepsy and adenoma sebaceum of the face.2 One study of 42 patients with astrocytomas found that 57% had TS, 14% had neurofibromatosis and 29% were normal.3

Eye care professionals should keep in mind that confirmation of a diagnosis of TS is often delayed, even in cases of infantile spasms, until other signs appear at a later age. Confirmed diagnosis of TS typically occurs at age 8 in mentally retarded children and at age 17 in people of normal intelligence.4

Neuroimaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to look for periventricular calcification is standard to make the diagnosis. Although 80% of TS cases occur as new mutations, genetic counseling is needed for confirmed cases.2 Complications with astrocytomas are uncommon. However, annual exams to monitor these lesions are recommended because exudative retinal detachments associated with astrocytomas have been documented.5

Discovery of astrocytomas in very young patients can be challenging because the unique granular calcified mulberry lesions (figure 2) may not develop until later in life. The lesions may initially appear as white, elevated translucent masses, which often extend from the optic nerve.1 This appearance can be mistaken for myelinated nerve fibers, which can lead to a delay in diagnosis of TS, or for a retinoblastoma for which enucleation may be considered.6

DMD is one of nine genetic, degenerative diseases that primarily affects voluntary muscles. Onset of DMD usually occurs in early childhood. Generalized weakness and muscular wasting may be noted in hip, pelvic, thigh and shoulder muscles. The disease is X-lined recessive and primarily affects boys. Their mothers are carriers and rarely exhibit symptoms.7

While the association between astrocytic hamartomas and TS and neurofibromatosis has been well established, there is currently no reported association with DMD. Unless other cases are reported in the future, this finding of an astrocytoma in a DMD carrier must be considered coincidental.

Dr. Collins is director of the U.S. Air Force optometry residency program at Wilford Hall Medical Center, San Antonio, Texas; Dr. Sheker is in residency at Indiana University College of Optometry; and Dr. Cebollero is director of optometry services at Yokota Air Base in Japan.

1. Reeser FH, Aaberg TM, VanHorn DL. Astrocytic hamartoma of the retina not associated with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1978 Nov;86:688-98.

2. Williams R, Taylor D. Tuberous sclerosis. Surv Ophthalmol 1985 Nov-Dec;30:143-54.

3. Ulbright TM, Fulling KH, Helveston EM. Astrocytic tumors of the retina: differentiation from phakomatosis-associated tumors. Arch Path Lab Med 1984 Feb;108(2):160-63.

4. Mullaney PB, Jacquemin C, Abboud E, et al. Tuberous sclerosis in infancy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1997 Nov-Dec;34(6):372-75.

5. Vrabec TR, Augsberger JJ. Exudative retinal detachment due to small noncalcified retinal astrocytic hamartoma. Am J Ophthalmolmol 2003 Nov;136(5):952-54.

6. Shields JA, Shields CL, Ehya H, et al. Atypical retinal astrocytic hamartoma diagnosed by fine-needle biopsy. Ophthalmology 1996 Jun;103(6):949-52.

7. The Muscular Dystrophy Association. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. http://www.mdausa.org/disease/dmd.cfm. Accessed January 9, 2006.