|

A 61-year-old Caucasian female presented with symptoms of blurred vision in both eyes for the past year and a half. She also reported seeing dark floaters in her vision that she described as having white halos surrounding them.

Her past ocular history was significant for a retinal detachment in the left eye four years earlier that was repaired with a gas bubble and laser. She then developed an epiretinal membrane in the same eye, which was treated with a vitrectomy, and then cataracts in both eyes, which resulted in cataract surgery two years prior. She felt her vision was good after the cataract surgery but now reported a painless progressive decline in her vision in both eyes with floaters. Her past medical history was unremarkable.

On examination, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 OD and 20/60 OS. Confrontation visual fields were full to careful finger counting OU, and the pupils were equally round and reactive with no afferent pupillary defect. The anterior segment was significant for trace cell in the anterior chamber of the right eye and 1+ cell in the left eye with trace flare. A posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) was present in both eyes with 2+ capsular opacification in the right eye.

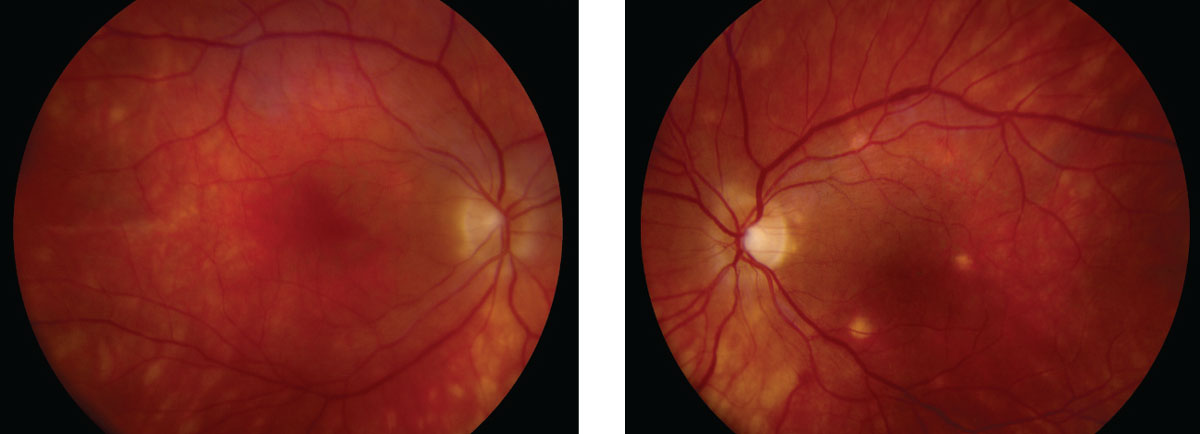

Dilated fundus exam showed a significant vitritis in both eyes. The optic nerves appeared healthy with small cups and good rim coloration and perfusion in both eyes. The arteries and veins were slightly attenuated. There was an absence of the fovea light reflex in both macules. Throughout the posterior pole and peripheral retina, there were obvious retinal changes (Figure 1).

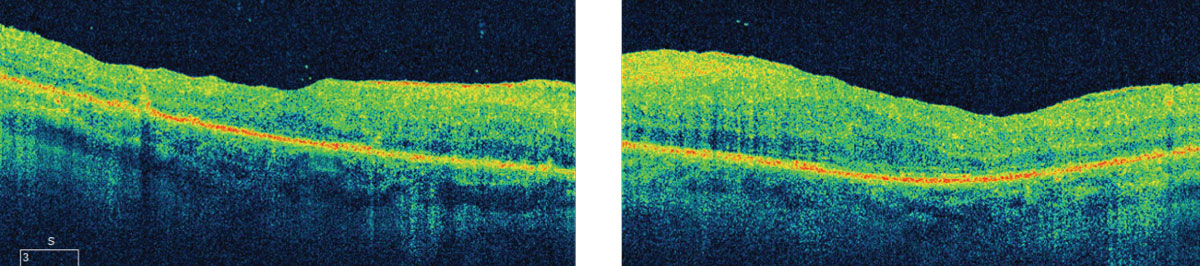

An optical coherence tomography (OCT) image was ordered as well (Figure 2).

Take the Retina Quiz

1. What additional tests would be helpful to confirm the diagnosis?

a. Fluorescein angiography.

b. HLA-A29.

c. Angiotensin-converting enzyme.

d. HLA-B9.

|

| Fig. 1. These fundus shots show noticeable changes to the patient’s retina. Click image to enlarge. |

|

| Fig. 2. These OCT images illuminate specific findings along the layers of the posterior segment, including the choroid. Click image to enlarge. |

2. What does the OCT show?

a. Neurosensory retinal detachment.

b. Cystoid macular edema.

c. Mild inner retinal thickening but no cystoid macular edema.

d. Loss of the IS/OS junction.

3. What is the likely diagnosis?

a. Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis.

b. Serpiginous choroiditis.

c. Birdshot chorioretinopathy.

d. Syphilis.

4. What is the best treatment?

a. Corticosteroids.

b. Observation.

c. Immunosuppressive agents.

d. Both a and c.

Discussion

Based on the history and the clinical presentation of multiple creamy white fundus lesions at the level of the choroid, with vitreous inflammation, we were very suspicious that our patient had “birdshot chorioretinopathy,” a rare autoimmune inflammatory condition of the choroid and retina. Blood work was performed, including HLAA29, which came back positive, thus confirming our initial suspicion of birdshot.

Birdshot retinochoroidopathy (BSCR) occurs in men and women in the fifth to seventh decade of life, mostly in Caucasian patients.2-3 The most common symptoms are blurred vision, increasing floaters and photopsia.2 As the disease progresses, night blindness and loss of color vision can occur.2 Our patient did have reduced color vision in both eyes; only seeing 6/11 Ishihara color plates in the right eye and 3/11 in the left eye. The hallmark of the disease is significant vitritis and multifocal patches of depigmented or hypo pigmented lesions that may be creamy yellow or orange in color. The ill-defined patches are typically round or oval in shape. Some will be elongated in a pattern that radiates toward the peripheral fundus. The striking feature of the lesions is the lack of chorioretinal scaring or hyper pigmentation at the margins that is often seen in other inflammatory conditions.

|

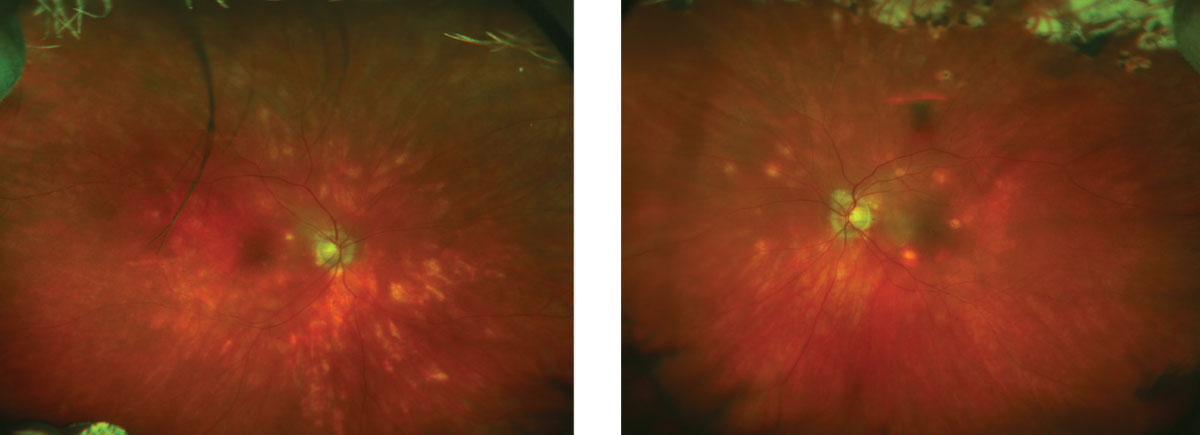

| These fundus images show the patient four years following her initial diagnosis. Click image to enlarge. |

The origin of the disease begins in choroid and later involves the retinal pigment epithelium. The diagnosis is usually made based on clinical presentation; however, it is also strongly associated with the HLA-A29 antigen.2-3 Researchers hypothesize that enhanced expression of self-peptides to T-lymphocytes through the A29 molecule or through molecular mimicry with microbial antigen is a key driver in the disease.3 Given this strong association with the HLA-A29 antigen, many believe that “HLA-A29 uveitis” is a more appropriate name for BSCR.3

Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) can help diagnose BSCR as well as the long-term follow up. The most common FAF finding is peripapillary confluent hypoautofluorescence and abnormal macular FAF. Peripapillary hypoautofluorescence is strongly related with age and disease duration. Global hypoautofluorescence (i.e., present in both the macula and extramacular region) suggests that hypoautofluorescence may be a marker for chronicity and severity of BSCR.4

BSCR is a chronic, slowly progressive condition that has bouts of remissions and exacerbations.2 Vision loss often occurs due the development of cystoid macular edema, which develops from chronic inflammation.2 The emphasis for treatment is to quiet the inflammation. Corticosteroids have been the mainstay in treatment with limited success. Immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine have also been used alone or in combination when corticosteroids for long term treatment.2 Cellcept (mycophenolate, Genentech) is thought to induce apoptosis of the lymphocytes as well as inhibiting recruitment of lymphocytes.

Our patient was treated with topical prednisolone acetate 1% and topical diclofenac 0.1% both QID, as well as oral corticosteroids and mycophenolate 1gm PO bid. The vitreous floaters improved but over the course of a few months she subsequently went on to develop CME in both eyes, which was treated with dexamethasone intravitreal implants (Ozurdex, Allergan). This helped to control the inflammation and improve her CME for several months, but her course continued to wax and wane. She ultimately had a Retisert (Bausch + Lomb) implant in both eyes, which resulted in resolution of her CME. Retisert is a 0.59mg fluocinolone acetonide time-release, sterile implant designed to deliver corticosteroid therapy to the posterior segment for approximately two and a half years.5 She continues to be closely followed; however, she also had developed elevated IOP due to the chronic steroid use, which is being treated with IOP lowering medications.

Dr. Butts is an optometry resident at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

|

1. Ryan SJ, Maumenee AE, Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Am J. Ophthalmol. 1980:89(1);31-45. 2. Agarwal A. Inflammatory Disease of the Retina. In: Gass’ Atlas of Macular Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia:Elsevier Saunders;2012:1038-43. 3. Herbort C, Pavesio C, LeHoang P, et al. Why birdshot retinochoroiditis should rather be called HA-A29 uveitis? Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(7):851-5. 4. Boni C, Thorne JE, Spaide RF, et al. Fundus autofluorescence findings in eyes with birdshot chorioretinitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(10):4015-25. 5. RETISERT [Package Insert]. Rochester, NY: Bausch + Lomb Incorporated; May 2012. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/021737s000TOC.cfm. Accessed February 7, 2019. |