Ease the Burden of GlaucomaThe July 2023 issue of Review of Optometry centers around one of the toughest diseases to diagnose and monitor: glaucoma. The 29th annual glaucoma report targets dozens of areas where some ODs struggle to move beyond the fundamentals. Check out the other articles featured in this issue:

|

Glaucoma—a lifelong, vision-threatening disease that requires ongoing management—is one of the most common conditions optometrists see in clinical practice. As primary eye care providers, ODs are in a prime position to not only identify patients with glaucoma, but also monitor and successfully treat the condition in the long-term.

“Glaucoma care is an ever-evolving field, and we have to adapt with it. New therapies, both topical and surgical, continue to emerge, scope expansion brings greater accessibility to already existing treatment options, imaging techniques constantly improve and new diagnostic tools emerge as well,” says Jessica Haynes, OD, a consultative optometrist at the Charles Retina Institute in Germantown, TN. “We have to be able to determine which treatment options are right for our patients and also which tools and devices are right for our practices.”

Below, ODs with extensive glaucoma experience share common management missteps—in no particular order—that can be detrimental to patients and providers, as well as clinical pearls and advice to help fellow optometrists optimize their approach to this disease.

Misinterpretation of the Evidence

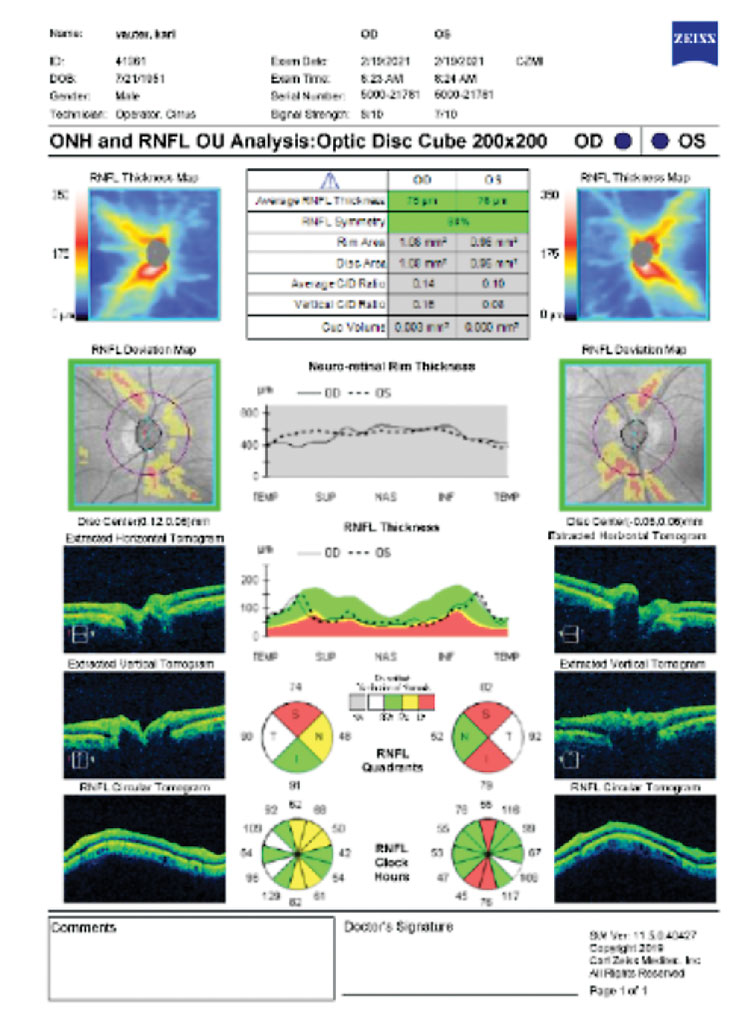

OCT has become a critical component of glaucoma diagnosis and management; however, this can lead to poor clinical decisions if the results are not interpreted appropriately. “Relying on OCTs regression analysis alone for diagnosing glaucoma is a major mistake,” notes Joseph Shovlin, OD, of Scranton, PA.

“When providers rely entirely on OCT regression analysis—ignoring potential for misinterpretation—it’s estimated that about 40% of patients diagnosed with glaucoma are being treated for something they actually don’t have,” he says. “This is one of the many reasons some estimates show up to 40% of patients being treated for glaucoma actually don’t have it. But, we’re certainly not suggesting not to treat when there is any concern or some doubt surrounding a diagnosis.”

There are number of reasons “red” (false positive) and “green” (false negative) disease can be misinterpreted, according to Dr. Shovlin. For example, common “red” disease causes include wrong birthdate entered (listed as younger); 15% to 20% of normal patients have a “split bundle defect” that may cause a dip into the red zone for regression analysis; and temporal (myopes) or nasal (hyperopes) vessel insertion with displacement.

In the case of “green” disease, Dr. Shovlin notes the potential causes such as wrong birthdate entered (listed as older) and patients whose retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) starts high and declines over time but still read as normal for their age (green depiction). “They might lose 10% and still read as green, but that is abnormal,” he says. “Look at the top printout for symmetry.”

The OCT “stoplight colors”—red/yellow/green—are derived from a relatively small database, explains Danica Marrelli, OD, clinical professor and assistant dean of clinical education at the University of Houston College of Optometry. “The fact that an area shows up in ‘red’ does not necessarily mean that there is disease, it could just be anomalous or unusual. Furthermore, the ‘green’ that we consider ‘good’ has a huge range—the color doesn’t let us know if the patient is close to the bottom of that ‘green’ or if they are close to the top of the range.”

When evaluating RNFL OCT findings, Dr. Marrelli advises that optometrists should be looking at the TSNIT or NSTIN curve (whichever your device shows) for symmetry and good modulation (peaks in superior/inferior zones), which is much more valuable than red/yellow/green,” she says. “We can both ‘over-call’ (false positive) and ‘under-call’ (false negative) glaucoma if we rely on the red/yellow/green.”

|

OCT showing areas designated as being outside normal limits but is merely a myope with a temporization of the RNFL peak. Click image to enlarge. |

Disease Misclassification

Effective glaucoma management can be hindered due to misclassification, according to Andrew Rixon, OD, an attending optometrist and the residency coordinator at the Lt. Col. Luke Weathers, Jr. VA Medical Center in Memphis, who explains that this involves not only misclassifying the extent of the disease but also the form of the disease.

“Initial misclassification, especially in cases where patients are under-classified, may set up a false sense of security leading the OD to be insufficiently aggressive with their therapeutic approach,” he says.

There tends to be an assumption that everyone has primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), but doing so can lead to negative outcomes, notes Dr. Rixon. For instance, angle-closure glaucoma, although rarer, is underdetected in North America.

Disease misclassification can be mitigated with the use of gonioscopy, which is reported to be performed in only about 50% of cases, Dr. Rixon explains. “Hone your gonioscopy skills and use it on all glaucoma suspects to appropriately classify the form of disease you are working with,” he recommends. “Angle closure spectrum of disease is more common than we think.”Leaving Tools in the Toolbox

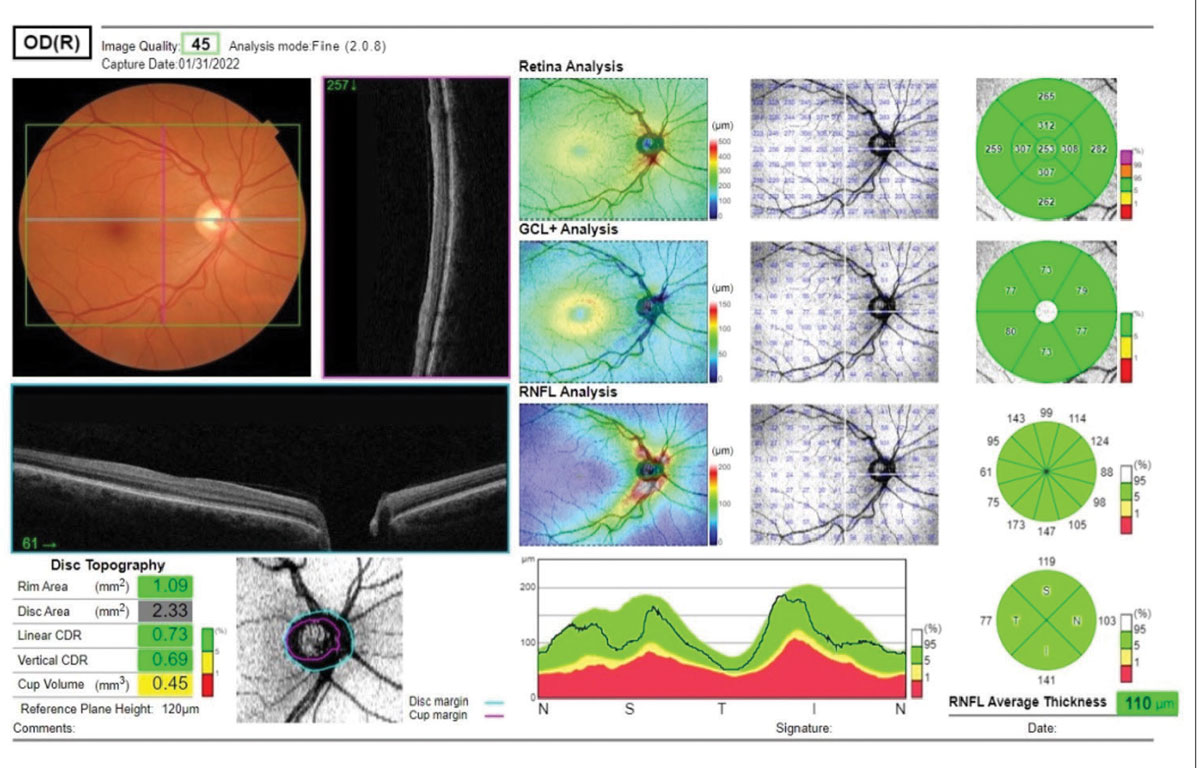

The diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of glaucoma is multifaceted, and shouldn’t be limited to a single approach. For instance, Dr. Marrelli emphasizes the importance of not relegating the clinical evaluation of the optic nerve and RNFL to an afterthought.“We have become so reliant on OCT,” she says. “This information is truly invaluable, but the clinical evaluation of the optic nerve, evaluating for diffuse or focal neuroretinal rim loss, notching, disc hemorrhage, beta zone peripapillary atrophy and RNFL dropout is really the first step in determining who has glaucoma. OCT provides excellent additional information but should not be the sole test for the diagnosis of glaucoma.”

Macular scans are another example of a useful tool that shouldn’t be forgotten. There is ample and compelling evidence that the macula can be damaged in early glaucoma, according to Dr. Marrelli, who notes that this is not visible on clinical exam.

“We can’t ‘see’ ganglion cell thinning in the same way that we can see nerve fiber layer or neuroretinal rim thinning, so the only way to observe this is by using OCT,” she explains. “Every OCT has a glaucoma-specific macular protocol that provides excellent adjunct information to the RNFL/optic nerve scans. The American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Patterns include macular imaging as part of the evaluation of glaucoma patients.”

In terms of therapeutic management, there are also abundant options—including many that optometrists tend to overlook. Dr. Marrelli says, “The general tendency of ODs who manage glaucoma is to prescribe a prostaglandin analog, and if the patient needs escalation of therapy, they refer the patient to ophthalmology.”

While she acknowledges that there are certainly exceptions to this pattern, Dr. Marrelli urges optometrists to consider the many new and efficacious treatments that are available before referral is necessary. This includes drugs like “latanoprostene bunod and netarsudil that target the trabecular outflow pathway—which we’ve not been targeting with drops for over 25 years—fixed combination drugs that help with adherence by reducing the complexity of the drug regimen.”

It is also important to think about options such as selective laser trabeculoplasty as first-line therapy, new drug delivery systems (i.e., sustained-release bimatoprost) and minimally invasive glaucoma surgery, according to Dr. Marrelli. “Even if an OD lives in a state in which they cannot perform laser or injected medication, those treatment options should remain in play for their patient.”

Dr. Shovlin underscores the value of working with a surgeon who is well-versed in the various MIGS procedures. “When any glaucoma patient requires cataract surgery, be certain to refer to someone eager to do MIGS,” he says. “It’s a great opportunity to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) at the time of surgery. Many cataract surgeons will forego that opportunity, so optometrists should take that into consideration at the time of referral.”

|

|

Several metrics are available for evaluation of a glaucoma suspect, including the ganglion cell layer analysis and the RNFL analysis. Also noted are disc topography metrics. Click image to enlarge. |

Initiating Treatment Without a Complete Picture

Rushing to treat and/or not gathering enough baseline data is another misstep ODs should avoid in glaucoma care, suggests Dr. Marrelli.“It is so important to obtain multiple IOP readings prior to initiation of treatment—even if you make the diagnosis of glaucoma on the first visit—in order to know where to set your target IOP,” she recommends. “Glaucoma is generally a slow process and in almost all cases we have time to gather good reliable data from which to base our treatment.”

When determining to treat vs. not treat patients for glaucoma, it is critical to avoid beginning intervention because of a single irregular factor, such as the patient having a large c/d ratio, notes Dr. Haynes.

“We have to consider numerous factors, including the size of the optic nerve, for example,” she says. “The patient with a large c/d ratio may have a large optic nerve size that contributes to the larger c/d ratio. Their c/d may be large, but their neuroretinal rim tissue is entirely healthy, their RNFL is robust and their ganglion cell layer (GCL) is normal.”

On the other hand, a patient could have glaucomatous cupping with a smaller c/d ratio because they have a smaller-sized optic nerve, explains Dr. Haynes. “When determining if glaucomatous structural damage is present, we have to consider the size of the optic disc, as well as the status of the neuroretinal rim, the RNFL and the GCL.”

Dr. Shovlin also recommends using corneal hysteresis data when available. “It’s a measure of the cornea’s ‘shock absorbing’ biomechanical properties,” he explains. “Overall, low hysteresis eyes tend to progress more quickly. Hysteresis and peak IOPs are the best predictors of who will progress fastest. It may help explain why some patients show little response to drops and have no progression or little progression over time.”

For example, eyes with high hysteresis may show very little drop in pressures but not change on OCT or field assessments. In these cases, there may be a tendency to add more drops or surgical procedures when it might not be needed. On the other hand, low hysteresis eyes get a better response to drops but actually need it. This is why it is so important to continue to carefully monitor for field and OCT changes, Dr. Shovlin advises.

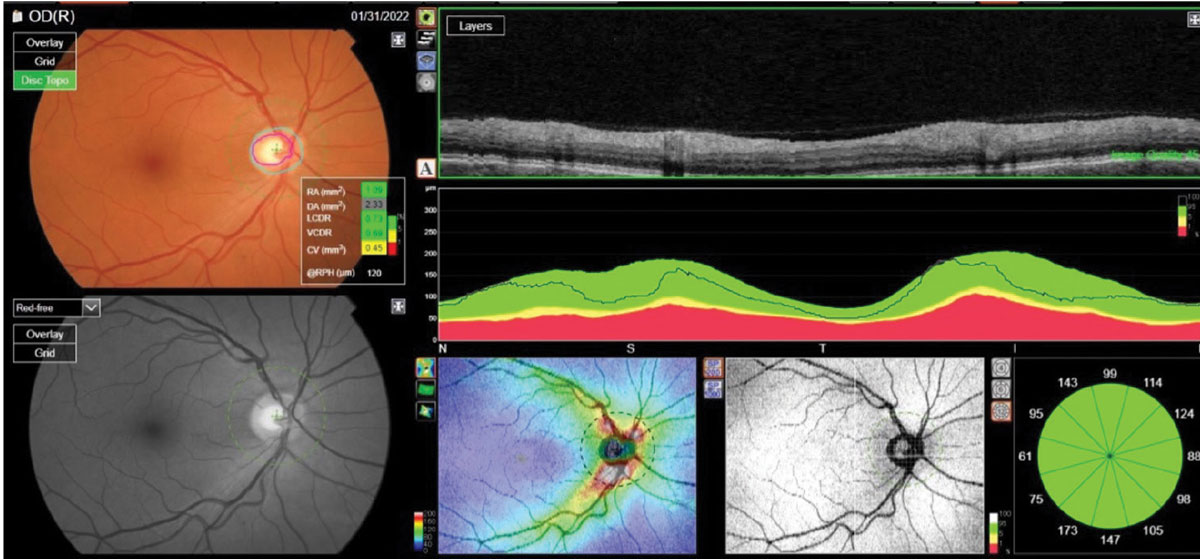

|

The reference database plots of a patient’s RNFL circle scan in an NSTIN format. Metrics of the right optic nerve raised questions; namely, a larger cup-to-disc ratio than seen clinically. Click image to enlarge. |

Too Much Emphasis on Static Target Pressure

While measuring IOP is a key component of glaucoma management, ODs should not base all of their decisions on a static target pressure, according to Dr. Rixon, who notes that this can result in robotic and non-personalized management. This, in turn, can cause under-treatment in some and over-treatment in others.“Decision-making should involve assessing structural and functional biomarkers,” he says. “We need to manage the disease, which involves adjusting therapeutic goals according to the disease behavior, not based on preconceived notions of IOP alone.”

IOP susceptibility is key, he emphasizes. “Look at what the disease is doing. If the patient’s IOP is higher than your initial target but their disease remains chronically stable, the nerve is unlikely to be susceptible to damage at the present level. In such a case, the initial target may have been unnecessarily aggressive, Dr. Rixon offers. “Target IOP is dynamic, and it is adjustable based on current and projected disease status. Resetting the target throughout the lifetime of management should be expected and is part of personalizing care.”

|

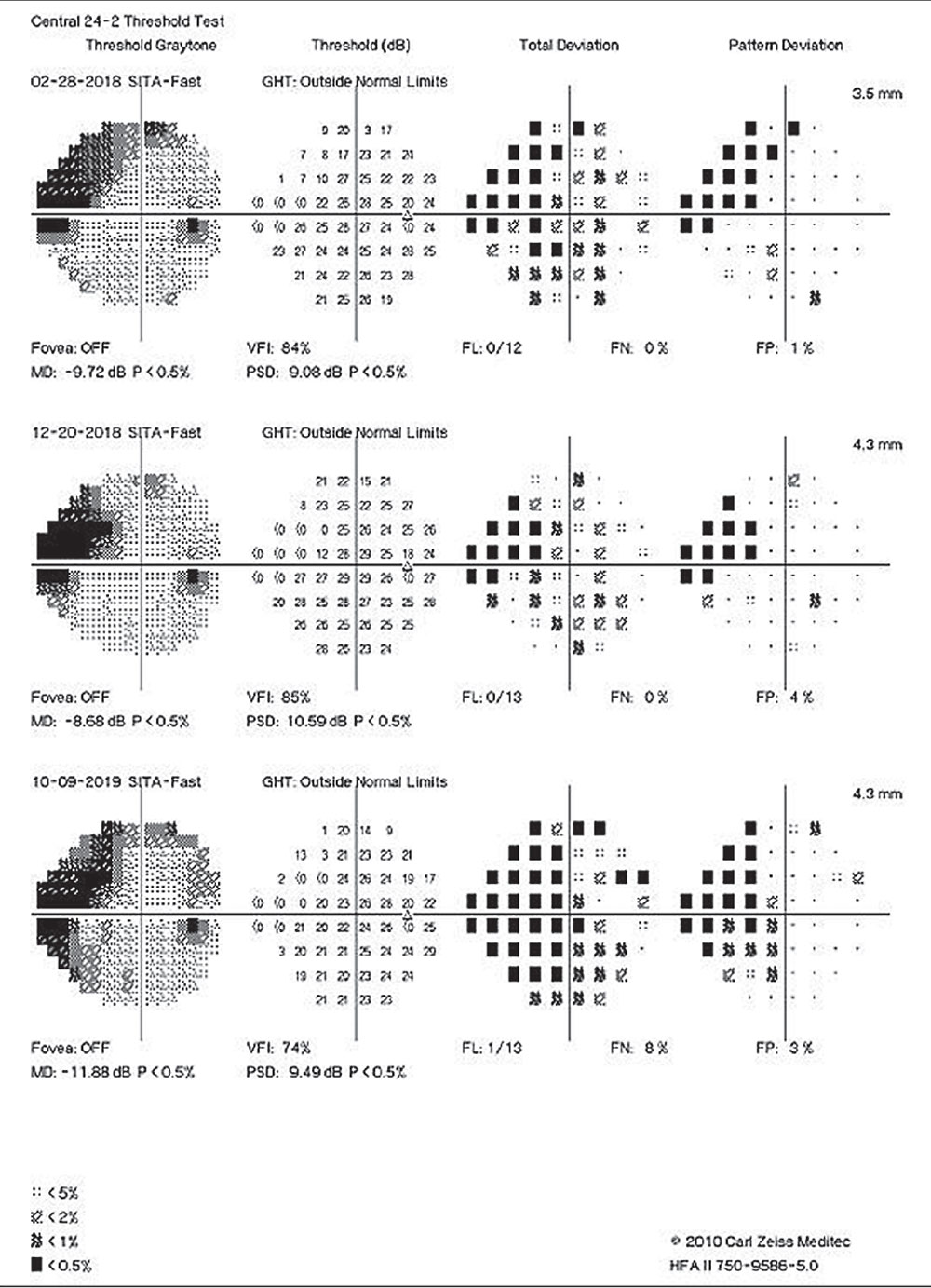

Progression Without Confirmation

A crucial aspect of glaucoma management is monitoring disease progression, and it is important not to jump to conclusions without adequate information. Therapy shouldn’t be escalated without clear confirmation of progression.

Both visual fields and OCT data can vary, notes Dr. Marrelli, while recommending that a field that looks like it has progressed should be repeated—usually twice—to confirm that suspicion. “We tend to think of OCT data as objective and infallible, but it, too, can vary from visit to visit,” she says. “The use of progression software is very helpful and can tell us not only if there is progression (using ‘event’ analysis), but also at what rate the progression is occurring. That rate of change is very important in deciding whether or not therapy needs to be enhanced.”

Another mistake is not getting enough visual fields in the first two years, according to Dr. Marrelli. “It has been suggested that six visual fields in the first two years is the best number in order to identify the ‘rapid progressors.’” While Dr. Marrelli knows this sounds like a lot of testing, she says, “it’s really only one every six months plus one additional one relatively soon after the first—which also helps to establish a good baseline.” After two years of visual fields, if the field looks relatively stable, you can “relax” a bit and back off on the frequency of the field testing, she advises.

When you have identified a patient as a fast progressor, you must be prepared to intervene accordingly. This may include, according to Dr. Rixon, earlier surgical intervention either in the optometric office where scope allows, or subspecialist referral.

ODs must also make sure that they are considering the rate of progression, notes Dr. Rixon. “Most POAG patients are not fast progressors, approximately only 10%,” he says. “Fast progressors are >2µm/year on OCT and -1.5-2dB/year on visual fields. Fast progressors are much more likely to lose function than their slower counterparts—assuming equal life expectancy.”

Skipping Re-baselining

Once progression has been confirmed and treatment escalated, it is important to re-baseline. Without this step, it can be difficult to gauge success, says Dr. Rixon. “You need to be able to assess how the intervention modifies the rate of progression to ensure you are taking the right approach.

“Comparing post-treatment rate of progression to a previously untreated or less treated state can lead to misinterpretation, which could lead to avoidable side effects and increased burden on the patient,” he continues.

Dr. Rixon recommends that ODs become familiar with how to re-baseline on the various visual field and OCT machines. “This should reduce the desire to intensive therapy soon after having just escalated it,” he notes. “The general recommendation is to hold off on additional treatment for approximately 12 months after the last intervention. If a sufficient number of tests are performed in that year, it should be enough time to elicit whether the last intervention modified the disease meaningfully.”

Failing to Consider Other Possibilities

It is important for optometrists to always consider masqueraders for neurologic and vascular diseases, conditions that might look like glaucoma, but aren’t, according to Dr. Shovlin. “A one eye, diffuse, one quadrant loss is likely not early glaucoma. It’s probably a deeper layer vascular cause such as central retinal vein occlusion or non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Generally, early glaucoma will show a narrow one quadrant loss.”Dr. Shovlin also recommends paying particular attention to disc pallor, in addition to rim erosion and matching what you observe with field loss.

“Homonymous macular atrophy with ganglion cell complex (GCC) assessment often represents previous demyelination or optic tract damage from a traumatic brain injury. Bilateral nasal GCC loss may represent a chiasmal lesion,” he says. “A right or left sided GCC may represent a posterior lesion. In glaucoma, the GCC loss should respect the horizontal midline on the temporal side. When things don’t add up, neuroimaging is indicated. There’s nothing more expensive than a missed/wrong neurologic diagnosis.”

|

Authors of a recent study advocate for better metrics to track and anticipate central visual field loss, owing to the high rate of progression seen in their research. Click image to enlarge. |

Clinical Pearls for Optimal Management

Mistakes like the ones discussed above can have a negative impact on both patients and optometrists. Keeping these missteps in mind while managing your glaucoma patients helps ensure optimal outcomes for all involved.“These mistakes can lead to (1) non-glaucomatous patients being diagnosed and treated unnecessarily, causing potential undue burdens such as financial, emotional, time and development of adverse treatment effects, and (2) glaucomatous patients not being treated or not being treated aggressively enough which can lead to lifelong, permanent visual disability,” says Dr. Haynes.

An easy first step, she notes, is ensuring that you are acquiring and looking at all the pieces of information necessary to make an appropriate diagnosis. At a minimum, this includes the following, according to Dr. Haynes: IOP, appropriate visual field testing, OCT imaging of the optic nerve showing both the RNFL thickness and GCL analysis, evaluation of the neuroretinal rim tissue—clinically and with OCT if available, determination of the optic nerve size—clinically or with OCT if available, pachymetry and gonioscopy.

After gathering all of these metrics, the next step is to perfect your interpretation skills. “This may include doing work to better understand your OCT instrument: it’s resolution capabilities, possible imaging errors that could occur, and how data can be visualized and analyzed including progression analysis,” says Dr. Haynes. “Obtaining the data is a good start, but you have to put the time in to become proficient at interpreting that data.”

When offering his advice for glaucoma management, Dr. Rixon emphasizes the importance of thoughtfulness and patience. “Don’t make rash decisions, collect the information and increase the certainty of your decision-making process before each intervention,” he urges.

Patient education is also a critical component of effective care and positive outcomes. Dr. Rixon recommends taking time to explain what glaucoma is, as well as why specific testing is needed and certain testing intervals are necessary.

“This should lead to increased buy-in and a shared decision-making approach,” he says, while also encouraging ODs to “embrace interventional care, regardless of what method you use to gauge adherence; non-adherence is a reality that needs to be considered.”

Effective glaucoma management is not one-size-fits-all and ODs must have the skills and knowledge to not only use the tools at their disposal, but also recognize the nuances of this condition.

“Although we can use the entire clinical picture to help predict outcomes and necessary interventions, none of us possess some magic formula, and therefore vigilant monitoring supplants any assumptions we might make,” concludes Dr. Rixon. “Each case and patient is unique, and different strategies for success may be required. We, as clinicians, have to be prepared to adapt as needed."