By Christopher A Clark, OD, PhD, and Dean VanNasdale, OD, PhD

The coronavirus is currently wreaking havoc in China and is quickly making its way around the world, with reported cases on every continent except Antarctica.1 While cases in the United States remain low—only 96 of an estimated 90,000 cases worldwide—health care professionals in every field should take precautions to protect themselves and their patients.1

The American Optometric Association issued a statement on February 25 addressing “anecdotal reports of conjunctivitis associated with COVID-19.”2 The American Academy of Ophthalmology issued an alert three days later to its members discussing the virus’s potential eye-associated problems.3 The risk to eye care professionals is thought to be due to respiratory droplets that primarily infect the respiratory tract and the conjunctiva. There is also the potential for transference via touching the eyes, nose or mouth. Because of this, eye care professionals could be the first contact for many patients with mild to no symptoms aside from conjunctivitis.

Recommended Steps:2

- Ask all patient presenting with conjunctivitis about any respiratory symptoms.

- Ask about any travel by the patient or their contacts to hot-spot regions, which included China, South Korea, Japan, Italy and Iran (as of March 1).

- Should any patient meet the criteria of conjunctivitis, respiratory symptoms and international travel, especially to a hot-spot region, the CDC recommends you immediately notify both infection control personnel in your clinic and your local or state health departments.

- When seeing patients with these symptoms, use goggles, gloves and respiratory masks (N-95).

- If you are the infection control person in your clinic, sanitize all patient contact areas, including the restroom, with traditional alcohol (65% to 95%).

- When possible, all personnel should maintain a six-meter distance from potential COVID-19 patients.

|

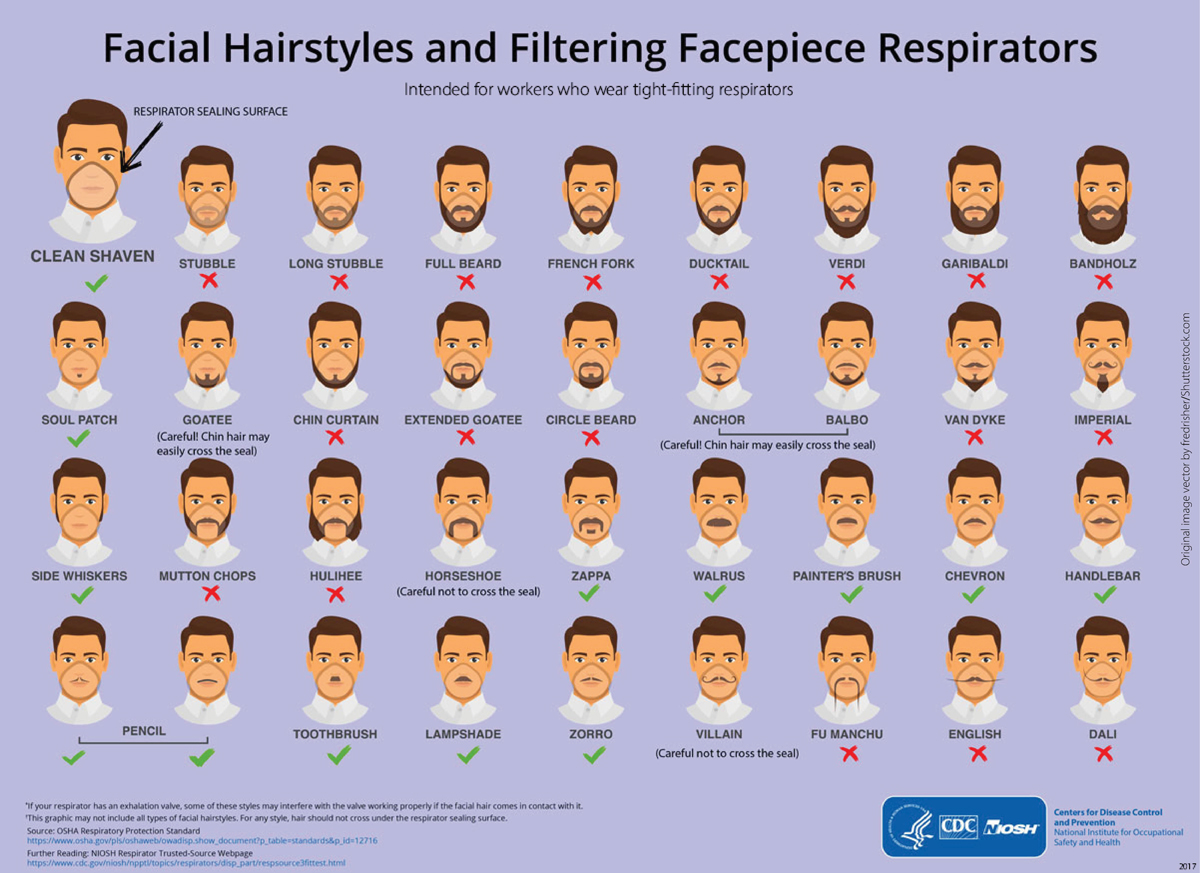

| Fig. 1. The CDC has provided a facial hair guide for practitioners who need to use an N-95 mask. Photo: CDC. Click image to enlarge. |

Other Clinical Considerations:

- The conjunctivitis presentation is similar to other viral infections with symptoms of injection, photophobia, irritation and watery discharge.

- Expect supply chain disruption, including both diagnostic tools and necessary medications.

- Consider triaging patients on the phone and train your staff accordingly.

Coronavirus Facts

There are seven known types of coronavirus that infect humans; the four most common are 229E (alpha coronavirus), NL63 (alpha coronavirus), OC43 (beta coronavirus) and HKU1 (beta coronavirus). COVID-19 is one of three novel coronaviruses, along with MERS-CoV (the beta coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome) and SARS-CoV (the beta coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome). All coronaviruses are RNA, meaning they have a more efficient adaptation method for survival compared with DNA-based viruses.

COVID-19 symptoms can begin as short as two days and as long as 14 days from initial infection. Other ocular signs and symptoms associated with all variations of coronavirus but have not yet been reported in COVID-19 include uveitis and subconjunctival hemorrhages. SARS also showed the presence of virus in the tear film.4

Other classes of coronavirus can last outside the body for up to three hours. Alcohol-based methods should be considered as the first-line option for sanitizing clinics, as other coronavirus strains have had questionable response to diluted bleach methods.5-7

Epidemiology

The current accepted mortality rate for COVID-19 is 2.3% based on the initial 72,314 cases from mainland China.8 Data based on the outbreak in South Korea, which is currently screening for COVID-19 in the general population, may lower that to 0.5%.3 Of those cases, the majority are mild (81%).3 The 25% of patients requiring hospitalization had coexisting disorders such as hypertension (15%) and diabetes (7%).3 The mean age of patients with COVID-19 is 50, and children appear to have a low probability of developing symptoms at this time.3

Cover Up

An N-95 mask is for medical personnel and is the current recommendation from the CDC and American Academy of Ophthalmology for clinical care of coronavirus suspects. N-95 blocks 95% of the particulates entering a properly fit mask. Because it requires close fitting to the face, facial hair is not recommended (Figure 1).9 They should be put on before entering the examination room and removed upon leaving. Disposable masks should be discarded immediately. Reusable masks should be sterilized between patients. Preparation is key, as some N-95 masks are currently backordered for two to four weeks due to panic buying, and the surgeon general has urged the public to stop purchasing them.

Supply Chain IssuesIn addition to respiratory masks, expect reduced access to any and all medical supplies. Be prepared to use alternate medications for virtually any condition. Delay non-essential treatments and diagnostics should supplies become limited. |

Currently, the CDC does not recommend any specific goggles for COVID-19. Goggles should fit snuggly across the face with minimum to no gaps.10 Indirectly vented goggles are recommended to prevent splashes and sprays.10 They should be put on before entering the examination room and removed upon exit. Much like masks, they need to be disinfected between patients. Face shields are acceptable.

The CDC recommends the use of gowns before entering the room with a known coronavirus patient and disposing of them immediately upon exit.9 Neck ties should not be worn, and hair should be worn tight against the head.

Triage

Good triage begins with scheduling and front desk staff. Prepare your entire staff with best-practice protocols. Any patients calling to schedule a red eye visit should be asked if they have any respiratory problems associated with the red eye and if they have traveled recently.2 As the virus becomes endemic to the United States, such travel inquiries will become unnecessary.

Should a patient with conjunctivitis answer affirmatively to both questions (respiratory problems and hot-spot travel), consider treating the patient over the phone or online. If that is impossible, schedule the patient at the end of the day or after hours to minimize potential transmission. Be prepared to transition patients quickly to examination rooms from the front desk to minimize cross contamination. If a significant outbreak develops within your community, triage all patients and consider forgoing all exams except the most urgent care until the outbreak subsides. Maintain a record of all red eye visits, especially viral conjunctivitis, for potential use should an outbreak occur in your community.

Further updates can be checked on the CDC website.

Dr. Clark teaches epidemiology and biostatistics at the Indiana University School of Optometry. He is the recipient of grants from the CDC/National Association of Chronic Disease. He can be reached at cac2@indiana.edu.

Dr. VanNasdale teaches epidemiology and public health at The Ohio State College of Optometry. He is the recipient of numerous grants from the CDC/National Association of Chronic Disease.

| 1. Coronavirus Updates: U.S. Death toll rises as virus picks up speed. New York Times. Accessed March 2, 2020. 2. American Optometric Association. CDC: U.S. coronavirus spread expected, ‘disruption may be severe’. February 26, 2020. Accessed March 2, 2020. 3. CDC, WHO. Alert: Important coronavirus updates for ophthalmologists. March 2, 2020. 4. Loon S-C, Teoh SCB, Oon LLE, et al. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in tears. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:861-3. 5. Sizun J, Yu MW, Talbot PJ. Survival of human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 in suspension and after drying on surfaces: a possible source of hospital-acquired infections. J Hosp Infect. 2000;46:55-60. 6. Casanova LM, Jeon S, Rutala WA, Weber DJ, Sobsey MD. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010; 76:2712–7. 7. Xie X, Li Y, Chwang AT, Ho PL, Seto WH. How far droplets can move in indoor environments–revisiting the Wells evaporation-falling curve. Indoor Air. 2007; 17:211–25. 8. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) outbreak in china summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. [Epub]. 9. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or persons under investigation for COVID-19 in healthcare settings. February 21, 2020. 10. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Eye Safety. July 13, 2013 www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/eye/eye-infectious.html. |