|

|

History

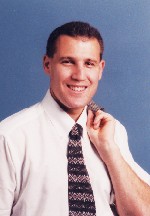

A 53-year-old white male presented with a chief complaint of headache as well as scratchy eyes. His history revealed systemic hypertension.

His best-corrected acuity was 20/25 O.U. at distance and near. External examination was unremarkable, and there was no evidence of afferent pupillary defect.

Anterior segment examination uncovered mild thickening of the epidermis and adnexa of the right eye.

Goldmann intraocular pressures measured 14mm Hg O.D. and 17mm Hg O.S.

The photographs demonstrate the pertinent findings.

|

|

| The patient presented with this appearance and a chief complaint of headache. |

Your Diagnosis

Discussion

The diagnosis in this case is varicella zoster virus (VZV) ophthalmicus and keratitis. VZV is a herpes virus that causes varicella (chicken pox) upon initial infection, and shingles or zoster on recurrence.

Additional tests for this patient might have included corneal sensitivity check, sodium fluorescein staining of the cornea to rule the presence of compromised epithelium, anterior chamber assessment to rule out iritis, retinal examination to rule out related retinitis (acute retinal necrosis) and blood work to rule out diseases of immunocompromised state (e.g., HIV).

VZV is a consequence of trigeminal nerve infection. The virus resides in a latent state in the dorsal root ganglion or trigeminal ganglion. When reactivated, it spreads from the ganglion along the sensory nerve to the skin, eye and adnexae.1-3 Only 20% of patients suffer reactivation.3 Second reactivation is even more rare and occurs mostly in immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients or those who suffer from AIDS, neoplasm or blood dyscrasia.1-8

Treat lid and conjunctival lesions with topical antibiotics and skin-drying agents (calamine lotion) four times daily for 10 to 14 days. Treat disciform keratitis with topical corticosteroids, such as prednisolone acetate b.i.d. to q.i.d., and taper slowly over a number of weeks. Systemic antivirals are the mainstay of treatment, specifically oral acyclovir 800mg five times daily for seven to 10 days, ideally initiated within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms.6-10

Oral acyclovir accelerates the resolution of skin rash and healing of skin lesions, reduces the period of lesion formation and viral shedding, and reduces the incidence of episcleritis, keratitis and iritis.10 Oral acyclovir also appears to reduce acute zoster-associated pain. Newer antiviral agents include famciclovir, pencyclovir triphosphate and valaciclovir.

Systemic corticosteroids used in combination with systemic antiviral medication appear to reduce acute zoster-associated pain and significantly improve patient function during the acute event, but do not consistently appear to affect long-term postherpetic neuralgia.10 Systemic corticosteroids along with a systemic antiviral agent is best limited to patients 50 years of age or older who have moderate-to-severe pain and who appear to have age-normal immunocompetence.

Established postherpetic neuralgia is difficult to treat. First, consider applying topical lidocaine-prilocaine cream or 5% lidocaine gel directly to the periorbital skin. If that is ineffective, consider the addition of a tricyclic antidepressant medication to the regimen, such as amitriptyline or desipramine at an initial low dose of 12.5mg to 25mg (at bedtime) and increase slowly.11

Direct local ocular treatment of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) toward reducing the damage associated with inflammation. Although topical antiviral agents are not commonly employed in the treatment of HZO keratitis, certain cases of delayed pseudodendritic keratitis have been reported to respond to topical antiviral treatment. Topical corticosteroids, used conservatively from b.i.d. to q.i.d. can be useful in reducing corneal and scleral inflammation as well as iridocyclitis and-unlike when used for the dendritic disease of HSV infection-do not appear to exacerbate any meta-herpetic keratitis that may be present. Carefully taper these preparations over a few weeks. If there is an epithelial defect, administer topical antibiotics to minimize the risk of bacterial infection.5-10

Neurotrophic ulceration is a major complication of HZO; persistent epithelial defect and corneal ulceration can be complicated by vascularization, superinfection and perforation. Persistent neurotrophic epithelial defect might be successfully treated with bandage contact lens wear or lateral or complete tarsorrhaphy.11-14 Cyanoacrylate glue or a conjunctival flap can be used in an attempt to arrest severe thinning that threatens corneal integrity. Severe necrotizing keratitis or postherpetic neurotrophic ulceration may lead to severe scarring or corneal perforation that requires corneal transplantation. If the eye has been quiet for a number of months prior to surgery, penetrating keratoplasty has a reasonably good chance of success.14 If the disease is active at the time of surgery, a tarsorrhaphy over the graft might be useful to preserve the corneal surface.

1. Liesegang TJ. Varicella-zoster virus eye disease. Cornea 1999 Sep;18(5):511-31.

2. McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999 Jul;41(1):1-14.

3. Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ, Kurland LT, et al. Population-based study of herpes zoster and its sequelae. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982 Sep;61(5):310-6.

4. Schmidbauer M, Budka H, Pilz P, et al. Presence, distribution and spread of productive varicella zoster virus infection in nervous tissues. Brain 1992 Apr;115 (Pt 2):383-98.

5. Kanski JJ. Disorders of the Cornea and Sclera. In: Kanski JJ. Clinical Ophthalmolgy. 4th ed. Boston: Butterworth-Heineman; 1999:96-155.

6. Straus SE, Ostrove JM, Inchauspe G, et al. NIH Conference: Varicella-zoster virus infections: biology, natural history, treatment and prevention. Ann Intern Med 1988 Feb;108(2):221-37.

7. McGreal JA Jr, Chronister CL. Infectious Diseases. In: Muchnick BG. Clinical Medicine in Optometric Practice. Philadelphia: Mosby; 1994:104-28.

8. Chern KC, Margolis TP. Varicella zoster virus ocular disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1998 Fall;38(4):149-60.

9. Harding SP. Management of ophthalmic zoster. J Med Virol 1993; Suppl 1:97-101.

10. Wood MJ, Johnson RW, McKendrick MW, et al. A randomized trial of acyclovir for 7 days or 21 days with and without prednisolone for treatment of acute herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 1994 Mar 31;330(13):896-900.

11. Watson CP, Evans RJ, Reed K, et al. Amitriptyline versus placebo in postherpetic neuralgia. Neurology 1982 Jun;32(6):671-3.

12. Bernstein JE, Korman NJ, Bickers DR, et al. Topical capsaicin treatment of chronic postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989 Aug;21(2 Pt 1):265-70.

13. Soong HK, Schwartz AE, Meyer RF, Sugar A. Penetrating keratoplasty for corneal scarring due to herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Br J Ophthalmol 1989 Jan;73(1):19-21.

14. Chen HJ, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for severe neurotrophic corneal ulcers. Br J Ophthalmol 2000 Aug;84(8):826-33.