|

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is a secondary glaucoma that is considered an advanced complication of ischemic retinal vascular disease. NVG accounts for 3.9% of all glaucoma cases.1 Most commonly related to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion (RVO) or ocular ischemic syndrome, retinal ischemia triggers a cascade of events that lead to aberrant blood vessel growth over the anterior iris and into the anterior chamber angle, also referred to as rubeosis iridis. IOP is adversely affected when fibrovascular tissue forms in the iridocorneal angle, impeding trabecular meshwork outflow. When left unchecked, this fibrous tissue leads to peripheral anterior synechiae and secondary angle closure.1

While patients with NVG can present without symptoms, they are more likely to report any combination of symptoms, including: redness, pain, light sensitivity, headache and decreased vision.1 In cases of secondary angle closure, headaches become more intense and may be associated with nausea and vomiting.2

| |

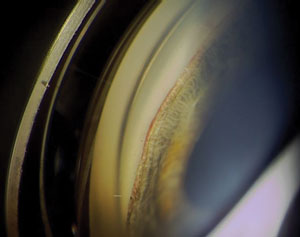

| Fig. 1. Slit lamp image of rubeosis iridies after CRVO. Photo: Lee Peplinski, OD. |

Etiology

Iris neovascularization at initial presentation is considered an indicator of poor visual prognosis. Entrance acuities can range from 20/40 to no light perception, with most presenting at 20/200 vision or worse.3,4 More than 95% of such eyes develop visual acuity of counting fingers or worse within one year.5 Despite the guarded prognosis, NVG is considered an ocular urgency because the potential for complete loss of vision, intractable pain and globe enucleation increases with delay in management (Table 1).6

When confronted with a patient who has neovascular glaucoma, a careful and thorough case history may be helpful in determining the underlying etiology. Patients with a history of poorly controlled Type 1 diabetes, with or without proliferative diabetes retinopathy, may certainly have diabetic NVG (Table 2). However, diabetic patients often have other health problems such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia.7 A patient who has these and other risk factors (Tables 2 and 3) and reports sudden, profound vision loss 60 to 90 days prior my have an ischemic CRVO.

In cases when no retinal ischemia is evident, ask about a history of carotid artery disease on the same side as the eye with NVG, as this is a risk factor for ocular ischemic syndrome due to carotid insufficiency.

If unsure, consider ordering a carotid duplex ultrasound.6 Additional ancillary testing and serology may be useful in staging the disease and isolating the cause of the retinal hypoxia and secondary NVG (Table 4).

| Table 1. Three Stages of NVG. | |||

| Stage | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Rubsosis iridis | Secondary open-angle glaucoma | Secondary angle closure glaucoma | |

| Symptoms | None to mild, redness, pain, photophobia | Redness, pain, photophobia, mild headache | Acute severe pain, headache, photophobia, nausea or vomitting |

| Pupils | Poorly reactive | Poorly reactive | Distorted, fixed, mid-dilated. May include eversion of pupillary margin |

| SLE | Neovascular tufts at pupillary margin NVI (irregular, non-radial vessels) | Positive NVI | Conjunctival injection (w/ ciliary flush), positive NVI +/- hyphema with corneal edema, aqueous flare |

| Tonometry | Normal IOP | Elevated IOP | Significantly elevated IOP (50+mm Hg) |

| Gonioscopy | NVA (Can occur without NVI) | Positive NVA, fibrovascular membrane formation | NVA + fibrovascular membrane formation, synechial angle closure |

Treatment

Management of NVG can be challenging and complex. It is often best comanaged in a team approach with subspecialists in both retina and glaucoma.

Whom you will call first will depend on disease severity based on your clinical assessment.

| Table 2. Incidence of NVG. IDDM1,2 • 5% chance in NPDR • 45% to 65% in untreated PDR • IDDM patients have 8% to 24% chance of NVD, NVE or NVI CRVO • 20% of all CRVOs are ischemic • NVG occurs in 45% of ischemic CRVOs • 8% to 10% of ALL CRVO patients 1. American Optometric Association. Optometric Clinical Practice Guide: Care of the Patient with Diabetes Mellitus. Available at: www.aoa.org/documents/CPG-3.pdf. accessed: September 18, 2015. 2. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). Update. DCCT Research Group. Diabetes Care. 1990 Apr;13(4):427-33. |

The mainstay of treatment is ischemia and IOP control. Patients who present with redness, pain, moderately elevated IOP (Stage 1 or 2 NVG) or some combination of those, will likely benefit from the initiation of topical medical therapy, such as IOP-lowering agents (e.g., b-blockers, alpha-agonists, CAIs), topical steroids and cycloplegics.

Remember, the use of prostaglandin analogues in lowering IOP in NVG patients is controversial, as they are pro-inflammatory.8

Regardless of disease stage, consult a retinal specialist for consideration of pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) with or without anti-VEGF treatment.

According to the Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS), reducing the amount of viable retina via PRP has been shown to inhibit, reduce and reverse neovascularization of the anterior segment.9

Using a spot size of 500µm to 800µm, up to 2,000 laser burns are applied to the outer retina using one of three methods: a slit-lamp delivery system, an indirect laser or an endolaser, if a vitrectomy is

warranted.

Anti-VEGF drugs such as Avastin (Genentech), Macugen (Gilead Sciences), Eylea (Regeneron), and Lucentis (Genentech) block angiogenic factors that promote new vessel proliferation.10

| |

| Slit lamp image shows rubeosis iridis. Photo: Paul Ajamian, OD. |

Several favorable reports exist regarding intravitreal and, to a lesser extent, intracameral administration of anti-VEGF agents in patients with NVG.11 While occasionally used in isolation, when visibility of the posterior segment is poor (i.e., hemorrhage), the trend is for the concomitant use of these drugs with PRP.

Surgical Options

In some cases, this combined treatment along with topical medical therapy is enough to control patients’ intraocular pressure. However, history shows that approximately 80% of patients with NVG will inevitably require surgical intervention.6,8 Therefore, a glaucoma specialist should also be consulted when confronted with NVG.

Glaucoma surgery may be indicated for refractory stage 2 cases in eyes with remaining functional vision. Ideally, surgery is performed three to four weeks after PRP, so the eye has had enough time to quiet down before being subjected to surgery.

The use of anti-VEGF drugs prior to trabeculectomy (with or without an anti-fibrotic agent such as mitomycin C or 5-FU) or valve implant surgery, can also improve outcomes.12

| Table 3. CRVO Risk Factors. | ||

| More Common Age Hypertension Hyperlipidaemia DM Contraceptive pills High IOP Smoking Less Common Behçet syndrome Sarcoidosis Wegener granulomatosis Myeloproliferative disorders Chronic renal failure Cushing syndrome Hypothyroidism Orbital disease Dehydration | 90% occur in patients age 55 or older Present in 73% of cases Present in 35% of cases Present in 10% of cases | |

With that said, most surgeons prefer tube shunt surgery to trabeculectomy because outcomes are less affected by inflammation. This is especially true in emergent cases (i.e., IOP of 65mm Hg) when there is no time to pre-treat the inflammation with PRP.

According to one study, regardless of the type of tube shunt, success rates are comparable.13 Unfortunately, when comparing surgical outcomes (sustained IOP reduction) between NVG patients and other forms of glaucoma, NVG patients continue to exhibit the worst overall results.14

When there is no visual potential, treatment is mainly focused on pain control. Sometimes, this can be accomplished medically with 1% atropine, topical steroids and IOP lowering eye drops.

In cases of corneal decompensation, bandage contact lenses may be used. If medical therapy fails to provide relief, consider recommending cyclodestructive procedures such as cyclocryotherapy or cyclophotocoagulation.

Retrobulbar alcohol injection is indicated after medical and surgical treatments have failed and in cases where the patient does not want the eye enucleated.

| |

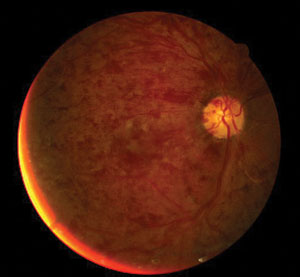

| Fundus image displays central retinal artery occlusion. Photo: Andrew S. Gurwood, OD. |

Overall Health

Lastly, neovascular glaucoma is associated with a high mortality rate.1 These patients are generally of poor health; consequently for the comanaging optometrist, communication with their primary care providers is vital. Their physicians can likely provide a more detailed general health history, while providing insight into their likelihood of following a prescribed treatment plan.

Based on your conversation, a complete medical work-up may be warranted, including the aforementioned lab studies.

The management of neovascular glaucoma is certainly challenging, and the diagnosis carries a poor prognosis. While new treatments (i.e., topical anti-VEGF therapy, pigment epithelium-derived factor and new treatment protocols (i.e., RISE & RIDE trials) are being developed, we need to remain diligent in educating patients on the importance of proper diet, regular exercise, compliance with prescribed treatments and keeping scheduled doctor’s appointments in the fight against proliferative eye disease.

The best chance of deferring vision loss secondary to neovascular glaucoma is undoubtedly to prevent it from developing in the first place.

Table 4. Preliminary Testing to Determine NVG Etiology |

2. Yazdani S, Hendi K,. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection for neovascular glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2007 Aug;16(5):437-9.

3. Kuang T, Ling Liu C, Chou C, Hsu W. Clinical experience in the management of neovascular glaucoma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004 Mar;67(3):131-5.

4. Tatsumi T, Yamamoto S, Uehara J, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation with simultaneous cryoretinopexy or intravitreal bevacizumab for neovascular glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013 May;251(5):1355-60.

5. Sivalingam A, Brown GC, Magargal LE (1991) The ocular ischaemic syndrome. Visual prognosis and the effect of treatment. Int Ophthalmol 15:15–20.

6. Sivak-Callcott J, O’Day D, Gass D, Tsai J. Evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of neovascular glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2001 Oct;108(10):1767-76.

7. Davis J, Chung R, Juarez D. Prevalence of Comorbid Conditions with Aging Among Patients with Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Hawaii Med J. 2011 Oct;70(10):209–13.

8. The Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Indications for photocoagulation treatment of diabetic retinopathy: Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report no. 14. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1987;27:239-53.

9. Olmos L, Lee R. Medical and surgical treatment of neovascular glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2011 Summer; 51(3):27-36.

10. Lüke J, Nassar K, Lüke M, Grisanti S. Ranibizumab as adjuvant in the treatment of rubeosis iridis and neovascular glaucoma-results from a prospective interventional case series. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013 Oct. 251(10):2403-13.

11. Martinez-Carpio PA, Bonafonte-Marquez E, Heredia-Garcia CD, Bonafonte-Royo S. [Efficacy and safety of intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in the treatment of neovascular glaucoma: systematic review]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2008 Oct. 83(10):579-88.

12. Luke J, Luke M, Grisanti S. [Antiangiogenic treatment for neovascular glaucoma and after filtering surgery]. Ophthalmologe. 2009 May. 106(5):407-12

13. Hong CH, Arosemena A, Zurakowski D, Ayyala RS. Glaucoma drainage devices: A systematic literature review and current controversies. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50:1:48-60.

14. Schwartz, KS, Lee RK, Gedde SJ. Glaucoma drainage implants: a critical comparison of types. Curr Opin Opthalmol. 2006;17:181-9.