|

A 64-year-old Caucasian male presented as a new patient in May with complaints of decreased vision OU. His spectacle Rx was from 2016, and he reported that his vision had gradually declined OU over the past several years, with his left eye “dropping off” rather significantly within the past few months.

|

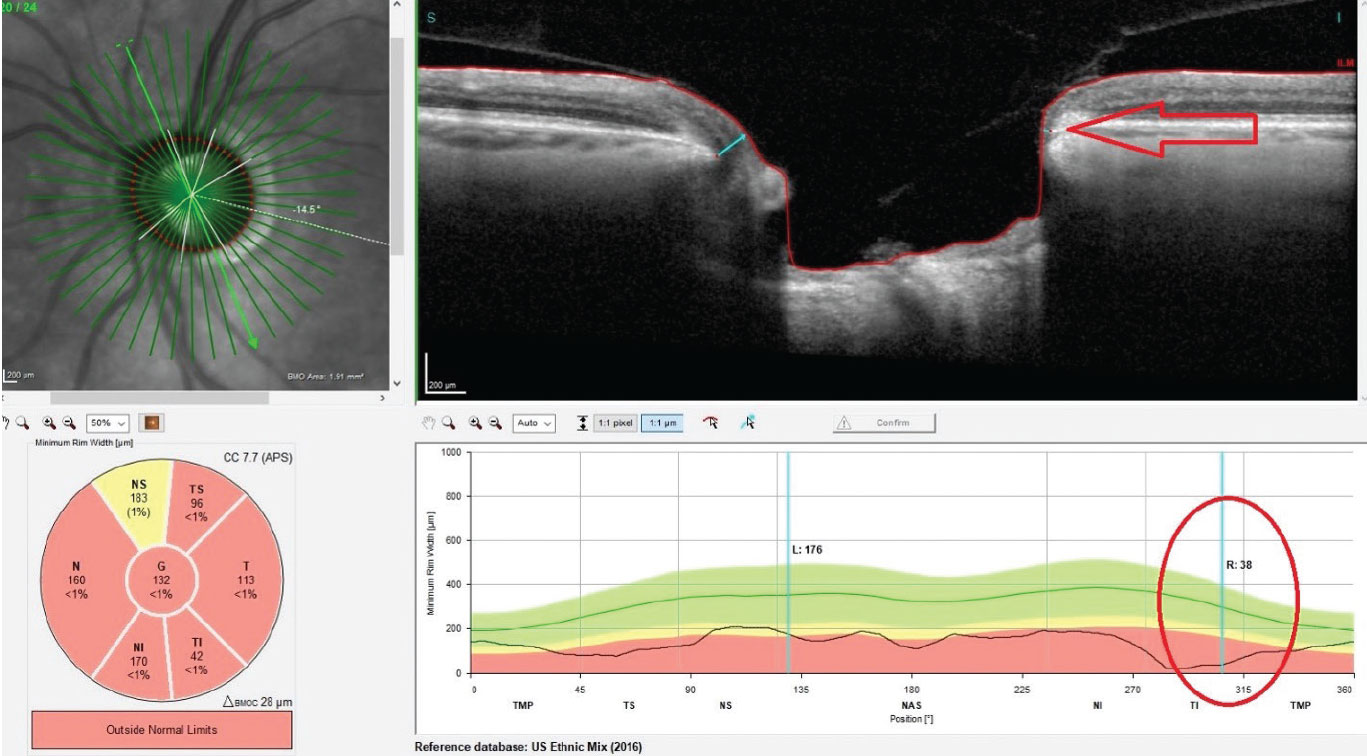

| Significant thinning in the neuroretinal rim OS. Inferotemporally, Bruch’s membrane opening is reduced to less than 38µm (circle and arrow). Click image to enlarge. |

The Case

The patient’s meds included lamotrigine, and he reported no drug allergies. His entering acuities were 20/30- OD and 20/50- OS. His pupils were equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation with an equivocal afferent pupillary defect OS. His best-corrected visual acuities were 20/25 OD and 20/40 OS through hyperopic astigmatic and presbyopic correction OS>OD. His extraocular muscles were full in all positions of gaze.

He had a “vascular problem” in his right eye several years ago that affected vision for several weeks but ultimately “returned to normal.” There have been no similar issues since.

A slit lamp examination of the anterior segment was completely unremarkable, with clear corneas, well-formed and quiet anterior chambers and a clear external examination. Applanation tensions were 18mm Hg OD and 19mm Hg OS at 2:46pm.

|

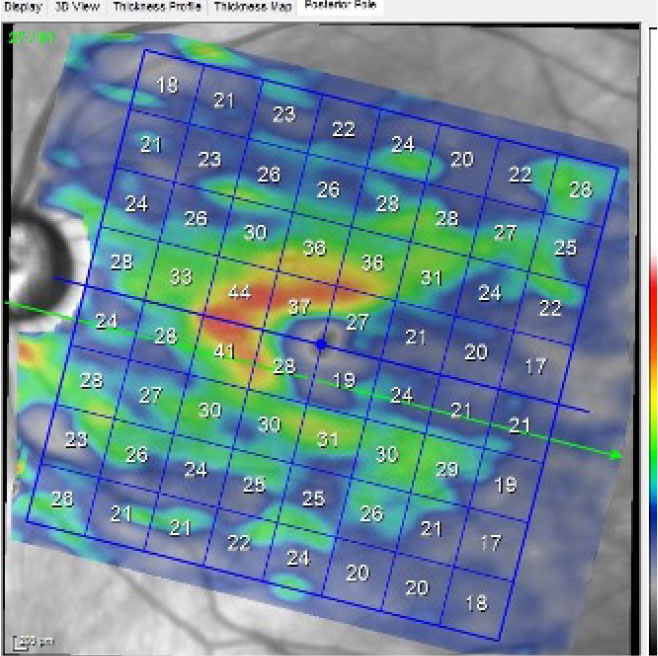

| A macular scan of the left eye, specifically isolating the ganglion cell layer. A normal ganglion cell layer falls within the 40µm range. Click image to enlarge. |

Through dilated pupils, the crystalline lenses were characterized by 1+ and 2+ nuclear sclerosis OD and OS, respectively, though acuities were somewhat worse than expected given the lenticular changes. Bilateral posterior vitreous detachments were present, as were epiretinal membranes outside the foveal avascular zone. The central foveal avascular zone was unremarkable at the slit lamp.

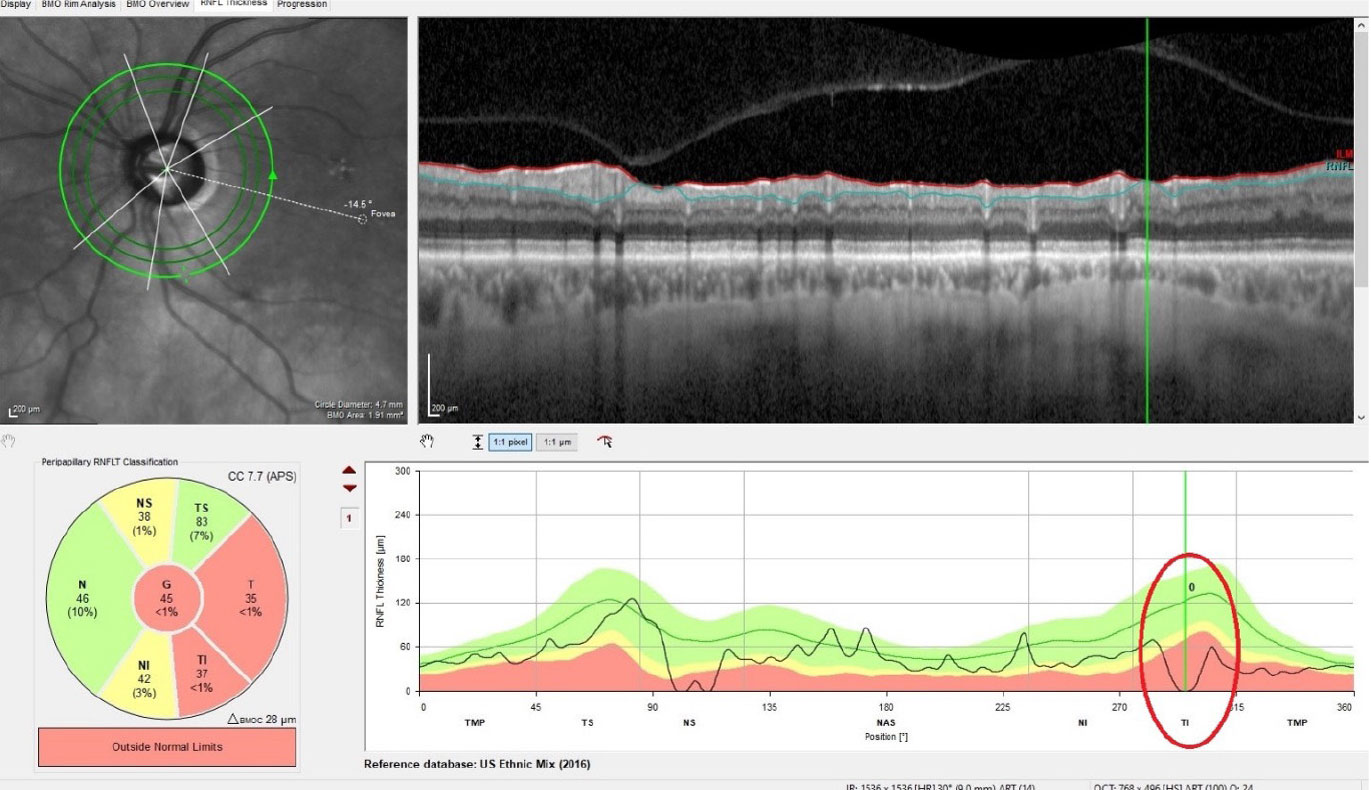

His cup-to-disc ratios were judged to be 0.70x0.70 OD and 0.70x0.85 OS, with significant thinning and notching inferotemporally OS. The right neuroretinal rim was also thin, and both optic nerves were of average size. The retinal vascular examination was characterized by mild arteriolarsclerotic retinopathy OU. The peripheral retinal examination was unremarkable.

Following the fundus evaluation, corneal pachymetry was obtained, and central corneal thicknesses were 490µm OD and 496µm OS. Optic nerve photos were taken, and the patient was asked to return in one to two weeks for optic nerve OCT and HRT3 imaging in the context of a glaucoma evaluation.

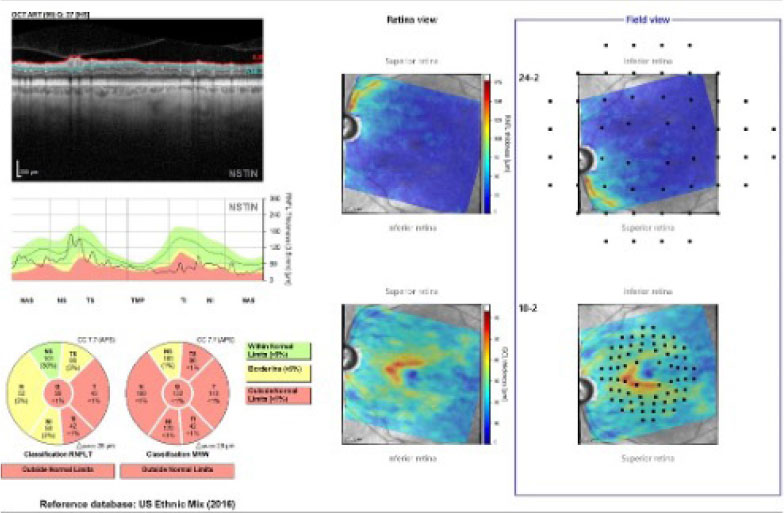

The patient followed up as requested, at which point his intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 22mm Hg OD and 26mm Hg OS at 8:53am. HRT3 imaging correlated well with the estimated cup-to-disc ratios previously recorded. OCT examination of the optic nerves confirmed neuroretinal rim loss OS>OD and perioptic retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) loss OS>OD, especially in the inferotemporal sector of the left eye. Macular ganglion cell body analysis demonstrated marked loss of cell bodies in the macula OS, greater below than above the horizontal raphe.

|

| The Hood report of the left eye, with concordance of the neuroretinal rim and perioptic RNFL damage. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

The findings of moderate OD and advanced OS glaucomatous damage are clearly evident in this case. Thin corneal pachymetry values and variable IOPs can play a role in delayed detection of glaucoma, though it doesn’t help that the patient had not sought care for five years.

While the diagnosis in this case is straightforward, management options vary from topical medication to selective laser trabeculoplasty to surgical intervention. Physician preference and experience play a role in setting a course for treatment. In this case, obtaining a visual field study may provide more insight, as, given the patient’s complaints of recent decreased vision and his advanced state of glaucomatous damage in the left eye, it’s not unreasonable to expect a field defect that involves fixation. The Hood report, along with the amount of structural damage, indicates that a 24-2 standard automated perimetry strategy is appropriate for this patient.

Stabilization of the glaucoma is very important, especially in the left eye, as the disease is more advanced OS. What ganglion cells remain in advanced disease tend to be more fragile, making matters even more challenging. At the completion of the second visit, I elected to medicate the patient with one drop of Xelpros (latanoprost ophthalmic emulsion, Sun Ophthalmics) OU HS to lower IOP and give me more time to determine the best course of action. Following two weeks of medication use, the patient’s IOPs were 12mm Hg OD and 13mm Hg OS.

I have yet to completely determine the extent to which the patient’s cataracts are affecting his vision, especially in the left eye, as the field testing is still pending. The likelihood of a field defect extending to fixation is a distinct possibility.

If we opt for cataract surgery, which will probably be the case, we can combine lens extraction with implantation of an iStent (Glaukos) inject device. Currently, this MIGS procedure is approved for implantation in the United States only when combined with cataract surgery. Its efficacy has been well documented, with a very low complication profile.1,2 More recently, data has indicated that these devices can be used in advanced glaucoma with good results, and they can also be successfully utilized in pseudoexfoliative glaucoma as well.3

|

| Thinning of the perioptic RNFL OS, with complete loss of the RNFL in one small sector inferotemporally. This area coincides with the thinned neuroretinal rim in the first image. Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

I am part of a European ophthalmology chat room, and, interestingly enough, a colleague recently posted a similar case of advanced glaucoma at the time of diagnosis, cataracts and decreased vision. Several of the doctors in the forum suggested immediately heading to cataract surgery with a combined trabeculectomy. While trabeculectomies can be very effective, they also are not without complications. I personally think there are less invasive ways to proceed initially (MIGS device, cataract surgery and perhaps topical therapy), reassessing as you move forward.

There are many viable strategies in cases like this, and ultimately, you will develop your own protocols based on what works for you. Just about all of them are acceptable options. Think about it like this: if you were the patient, with your expertise in the matter, how would you want the plan to proceed?

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heidelberg Engineering and Glaukos.

1. Popovic M, Campos-Moller C, Saheb H, et al. Efficacy and adverse event profile of the iStent and iStent inject trabecular micro-bypass for open-angle glaucoma: a meta-analysis. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2018;12(2):67-84. 2. Voskanyan L, García-Feijoó J, Belda JI, et al. Prospective, unmasked evaluation of the iStent inject system for open-angle glaucoma: synergy trial. Adv Ther. 2014;31(2):189-201. 3. Clement CI, Howes F, Ioannidis AS, et al. One-year outcomes following implantation of second-generation trabecular micro-bypass stents in conjunction with cataract surgery for various types of glaucoma or ocular hypertension: multicenter, multi-surgeon study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:491-9. |