A 64-year-old white male presented for a complete eye health examination. He complained of slight blur at distance and near through his current spectacles, which were approximately six years old.

His current medications included atenolol, enalapril, Lipitor (atorvastatin, Pfizer), hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), coumadin and Detrol LA (tolterodine, Pfizer). He reported no allergies to medications.

His medical history is significant for atrial fibrillation, three coronary artery bypass grafts five years earlier and bilateral iliac artery bypass surgery three years earlier. He reported partial bilateral carotid occlusion but did not need surgery at the time of the initial examination.

Diagnostic Data

Entering visual acuity was 20/25 O.D. and 20/30 O.S. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 O.U. through hyperopic astigmatic presbyopic correction. Pupils differed in size5mm O.D. and 4mm O.S.but were otherwise normally reactive to light and accommodation. There was no afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motilities were full in all positions of gaze.

A slit lamp examination of his anterior segments was completely unremarkable except for a faint anterior stromal scar off the visual axis in the left cornea secondary to an old foreign body. Anterior chamber angles were grade III O.U. by the Von Herrick method. Intraocular pressures were 25mm Hg O.D. and 27mm Hg O.S.

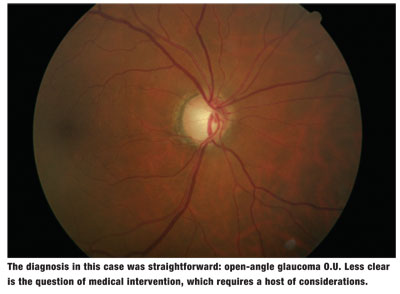

Through dilated pupils, his crystalline lenses were clear. A prominent vitreous base was observable O.U. Cup-to-disc ratios were 0.75 x 0.75 O.D. and 0.55 x 0.70 O.S., with thinned neuroretinal rims inferiorly and superiorly O.U. The neuroretinal rims did not conform to the inferior-superior-nasal-temporal (ISNT) rule. The optic discs were normal size. The macular evaluations were unremarkable O.U. The vasculature O.U. was characterized by grade II hypertensive retinopathy and grade III arteriolarsclerotic retinopathy. His peripheral retinal examinations were remarkable for scattered areas of pigmented cystoid, as well as 360 degrees of reticular degeneration O.U.

He returned in three weeks for a full glaucoma evaluation, at which time his IOPs were 25mm Hg O.D. and 26mm Hg O.S. Central corneal thicknesses measured 531m O.D. and 520m O.S. Threshold visual fields were moderately reliable and demonstrated paracentral areas of decreased sensitivity that generally conformed to the areas of neuroretinal rim thinning O.U. Gonioscopy demonstrated grade IV open angles with a moderate amount of trabecular pigmentation. Optic nerve imaging confirmed significant neuroretinal rim loss and associated thinning of the perioptic nerve fiber layer. Stereo nerve images were also obtained.

I diagnosed the patient with open-angle glaucoma O.U., with additional risk factors of significant cardiovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease.

This appears to be as straightforward a case of initially diagnosed glaucoma as there can be. While many optometrists do not treat glaucoma, those who do would consider this case to be relatively benign and easily managed in the initial stages.

Of course, once you make the diagnosis of glaucoma, the next step is to determine the initial intervention. In the

But here in the

In this patients case, I chose to begin medical therapy to control the glaucomatous optic neuropathy. The subsequent question: Which medication is best to initiate therapy in this patient?

Like many doctors, my first-line glaucoma drug is usually one of the prostaglandins, primarily because of their safety profile, high efficacy and simple, easy-to-use once-a-day dosage. Some prostaglandins can reduce IOP by 40% or greater in some patients on initial monotherapy.

But, the out-of-pocket costs for prostaglandins can be high, especially when you consider that a newly diagnosed glaucoma patient has no idea how much the medications will cost until the prescription is filled. For that reason, until I have been able to evaluate the efficacy of a particular medication, I always use samples of the medications. (I gave this patient a sample of Xalatan [latanoprost, Pfizer], 1 drop O.U. h.s., and scheduled him to return in two weeks to measure its effect on his IOP.)

Yet, obtaining samples of these medications is sometimes difficult. Many optometrists have complained over the years that they are not detailed with pharmaceuticals as often as our non-optometric colleagues are. In recent years, though, most ophthalmic pharmaceutical companies have begun to embrace optometry and, in particular, spend more time in detailing those O.D.s who prescribe more medications. (Drug reps now visit O.D.s an average 7.4 times a year, compared with 6.8 times a year in 2004, according to the 2006 AOA Scope of Practice Survey.) But, there is still room for improvement.

Of course, pharmaceutical companies are prudent to spend professional marketing dollars where they get the highest return on investment. But, the system for tracking prescriptions written by O.D.s is not as accurate as it should be. I have had several of my prescriptions filled with another providers name attached to it. Another problem: Many prescription tracking systems use DEA numbers as the primary tracking identifier, and many O.D.s do not have DEA numbers.

In any event, we should treat our patients as we would want to be treated if we were in their shoes. While most prostaglandins do work well with no side effects, that is not always the case, and that dictates a change in medications.

So, I think the best course is for us to initially dispense to the patient a sample of the medication. The sample isnt just a freebieits a method to evaluate the drugs safety and efficacy for a particular patient. If we dont have the sample, is it really fair to our patients to use their dollars to trial a medication? I dont think so.

That said, we should not habitually supply our chronic patients with sample medications for the long haul. For those truly in need of assistance, there are a variety of ways that patients can obtain their medications. (See The Cost of Doing Business, February 2007.)

If you have a sample of the chosen medication, by all means dispense it, evaluate it and, if it works, write a prescription for it. But if you dont, then dont obligate the patient to use that particular drug unless you truly feel that it is in the patients best interest. Eventually, the pharmaceutical companies will detail optometrists more regularly; this will trickle down to more precise and more effective care for our patients. But, until they do, consider writing prescriptions for those products and companies who support you, as long as the patient gets the best care (both therapeutically and financially) you can provide.

1. AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 9. Comparison of glaucoma outcomes in black and white patients within treatment groups. Am J Ophthalmol 2001 Sep;132(3):311-20.