|

A 65-year-old Black male presented with acute redness, tearing, soreness and pain OS of five days’ duration. He did not complain of reduced vision. He said the pain was 5 out of 10 and that he had similar symptoms in right eye, which spontaneously resolved one week prior. His past ocular history included blunt trauma OS with epiretinal membrane formation and an episode of non-granulomatous uveitis of unknown etiology some 10 years ago.

Medical history included discoid lupus, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Raynaud’s, osteomyelitis of the extremities and left hip, anemia, peripheral neuropathy, renal failure, cerebral vascular accident and rehabilitated substance dependence. His medications included Plaquenil 200mg BID since 2006, metoprolol, nifedipine, warfarin and acetaminophen.

Diagnostic Data

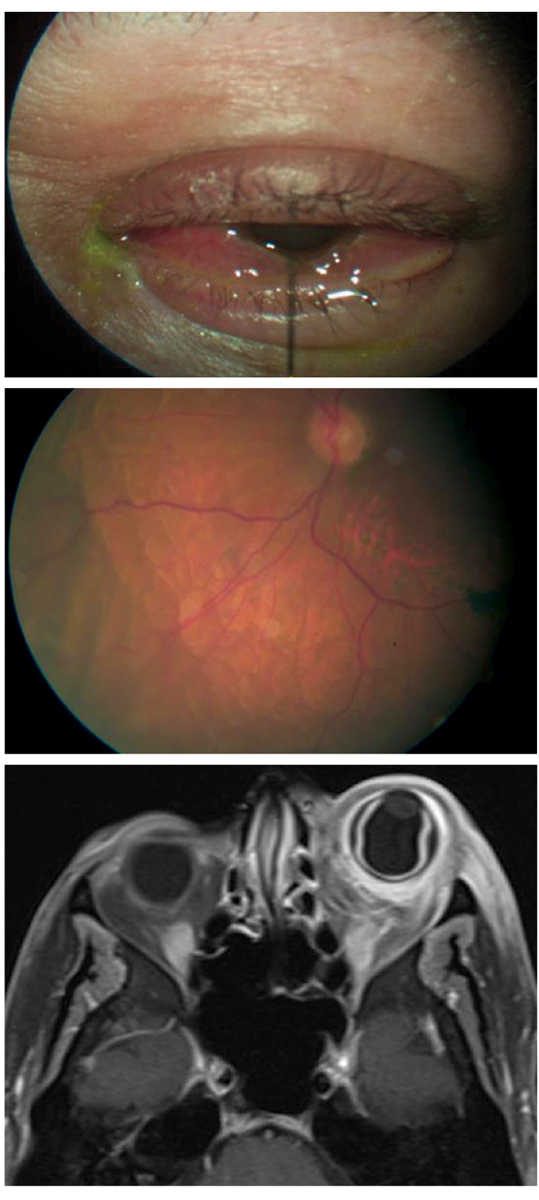

His best-corrected visual acuities were 20/25-2 OD and 20/40 OS at distance and near. His pertinent external findings by gross observation are demonstrated in Figure 1. Pupils and ocular motilities were normal. Confrontation visual fields were constricted. Refraction was not completed due to the emergent nature of the presentation.

Biomicroscopy OD revealed normal and healthy anterior segment structures. Examination OS uncovered diffuse injection with tenderness of the external lids, palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva. There were no cells in the anterior chambers of either eye, the lenses were well centered and there was no evidence of vitritis, OU. Goldmann applanation tonometry measured 10mm Hg OU. The dilated fundus exam was normal OD. The left eye (Figure 2) demonstrated an epiretinal membrane and pigment disruption of the macula secondary to previous trauma. There was no evidence or neurosensory retinal detachment or frank choroidal folds in either eye. Orbital MRI is also available (Figure 3).

|

|

Figs. 1-3. What do these images suggest about the nature of this patient’s condition? Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Additional studies included Hertel exophthalmometry to document the presence or absence of proptosis, the phenylephrine vessel blanch test to identify the depth of the inflammation and neuroimaging to rule out space occupying etiologies.

The diagnosis in this issue is orbital pseudotumor (OPT) with an associated choroidal detachment OS. Orbital pseudotumor, also referred to as idiopathic orbital inflammation syndrome, is a rare benign inflammatory condition involving the orbit that may involve single or multiple structures with the potential for extraorbital extension.1-16 The disease was first described in 1905 by Birch–Hirschfeld but continues to have a poorly understood etiology.1-16

Hypotheses of autoimmune origin mediated by both B and T lymphocytes have been reported.4 Viral, inflammatory, genetic and environmental factors have been implicated as triggers.4,9,10 Lower socioeconomic status, high body mass index, young age, use of oral bisphosphonate (bone density agonist), lithium (mood stabilization) and chemotherapies are documented risk factors as well.10,12 The disease is known to be associated with rheumatological disorders such as Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, giant cell arteritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis and rheumatoid arthritis.10-14

The condition is characterized by aggregates of mixed inflammatory cells, which include myofibroblastic spindle cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells.3-5 As the condition becomes chronic, fibrosis occurs.3-6

The condition is not unique to the orbit and has been described in almost any location within the body, with no age or sexual predilection.4 Orbital inflammatory pseudotumor ranks third after Graves’ disease and lymphoproliferative diseases for producing orbital pathology and accounts for approximately 5% to 8% of all orbital masses.4-6

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Presentation includes acute, subacute or chronic unilateral periorbital pain and photophobia in the setting of conjunctival chemosis, proptosis, injection around the extraocular muscle insertions, diplopia (extraocular muscle motility restriction) and variable visual disability and optic disc edema.1-16 In adults, the condition tends to be unilateral; however, in children, bilateral presentation is not uncommon.4,10 Iritis is a typical finding in the young and often indicates disease with a guarded prognosis.4

OPT is a diagnosis of exclusion.4,10,14-16 Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms, laboratory testing which rules out other etiologies and neuroimaging.1-16 Orbital inflammatory disease may result from infection, space-occupying lesions, hemangiomata, myositis, thyroid eye disease, dacryoadenitis, other rheumatologic inflammatory orbital lesions (Wegener’s granulomatosis) as well as others.1-16

The diagnostic evaluation of a patient suspected of having OPT should include:4,10,11

- a complete blood cell count with differential and platelets (CBC c diff and platelets-hematologic disease)

- electrolytes (kidney function)

- Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR-general inflammatory disease)

- antinuclear antibodies (ANA-lupus)

- antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA-polyangiitis such as Wegener’s granulomatosis)

- angiotensin-converting enzyme level (ACE-Sarcoidosis)

- rapid plasma reagin test (RPR-syphilis)

- thyroid function tests (TSH-thyroid stimulating hormone, triiodothyronine-T3, thyroxine-T4, thyroglobin)

- serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP-multiple myeloma, serum protein disorders)

- neuroimaging of the orbits

Cerebrospinal fluid examination should only be performed when needing to exclude lymphoma.4 While some propose biopsy as the best method of identifying the pathology and forming a treatment plan, it is generally not indicated unless orbital malignancy is suspected, treatment is ineffective or there is evidence that the lesion has extended outside the orbit.4-7,10-16

Oral and intravenous corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment.1-15 In cases where steroid treatment is ineffective, other options include oral and intravenous immunosuppressives (methotrexate, cyclophosphamides, infliximab), antimetabolite agents, lymphocyte inhibitors, T-cell calcineurin inhibitors, antineoplastic agents, radiotherapy and surgical excision.12-14 Surgical excision is considered only in rare localized cases.12-16

Prognosis

Most patients demonstrate complete remission after treatment.1-12 In 35% of patients, only partial relief is obtained.12 In 2% of cases, no remission occurs.12

This patient was referred to general ophthalmology and a retina specialist, who confirmed the findings. The choroidal detachments required no retinal intervention and resolved as the condition rapidly responded to an aggressive regimen of oral steroids. All systemic laboratory testing was negative and there were no residual losses from the event. Today, they remain stable with good vision, no cosmetic evidence of the event, no pain or symptoms and no history of recurrences.

The choroid is the vascular layer of the uveal tunic of the eye. Choroidal detachment may occur when the potential space (suprachoroidal space) that exists between it and the sclera becomes filled with fluid secondary to decreased intraocular pressure (hypotony) or choroidal effusion (transudative-medications, systemic diseases producing ocular inflammation and scleral abnormalities).17-20 While there are few papers that report associated serous retinal detachment or choroidal detachment with OPT, the association exists either directly (rare) or secondary to the systemic inflammatory disease that produced the OPT.17,19 In most instances, management of the underlying oculosystemic disease along with the management of the OPT is sufficient to assist the resolution of the retinal pathology.17-20

Dr. Patel is an attending optometrist at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, a clinical educator at Salus University and a private practice owner. He is also a Lt. Col. of the U.S. Air Force. He has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Gurwood is a professor of clinical sciences at The Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. He is a co-chief of Primary Care Suite 3. He is attending medical staff in the department of ophthalmology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Jackson H. Pseudo-tumor of the orbit. Br J Ophthalmol. 1958;42(4):212-24. 2. Dinga ZX, Lip G, Chong V. Idiopathic orbital pseudotumour. Clinical Radiology. 2011;66(9):886-892. 3. Tedeschi E, Ugga L, Caranci F, et al. Intracranial extension of orbital inflammatory pseudotumor: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(2):29. 4. Jacobs D, Galetta S. Diagnosis and management of orbital pseudotumor. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13(6):347-51. 5. Shi JT, An YZ, Sun XL, Li B. Clinical and pathologic analysis of orbital pseudotumor. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2003;39(2):81-6. 6. Szabo B, Szabo I, Crişan D, Stefănuţ C. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory pseudotumor: case report and review of the literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(3):927-30. 7. Mombaerts I, Rose GE, Garrity JA. Orbital inflammation: Biopsy first. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(5):664-9. 8. Khochtali S, Zayani M, Ksiaa I, et al. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome: Report of 24 cases. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2018;41(4):333-342. 9. Leo M, Maggi F, Dottore GR, et al. Graves' orbitopathy, idiopathic orbital inflammatory pseudotumor and Epstein-Barr virus infection: a serological and molecular study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(5):499-503. 10. Sarkar S. Bilateral Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation Syndrome in an adult patient: A rare case report. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2018;32(4):334-337. 11. Zhang XC, Statler B, Suner S, et al. Man with a swollen eye: nonspecific orbital inflammation in an adult in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2018l;55(1):110-113. 12. Herrera I, Kam Y, Whittaker TJ, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced orbital inflammation in a patient on chronic immunosuppressive therapy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):51. 13. Young SM, Chan ASY, Jajeh IA, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of orbital inflammatory disease in Singapore: A 10-year clinicopathologic review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3):182-188. 14. Taylan A, Karakas B, Gulcu A, Birlik M. Bilateral orbital pseudotumor in a patient with Takayasu arteritis: a case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(5):743-6. 15. Yeşiltaş YS, Gündüz AK. Idiopathic orbital inflammation: review of literature and new advances. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2018;25(2):71-80. 16. Mombaerts I, Bilyk JR, Rose GE, et al. Consensus on diagnostic criteria of idiopathic orbital inflammation using a modified delphi approach. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):769-776. 17. Shapiro BL, Petrovic V, Lee SE, et al. Choroidal detachment following the use of tamsulosin (Flomax). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(2):351-3. 18. Kurtz S, Moisseiev J, Gutman I, Blumenthal M. Orbital pseudotumor presenting as acute glaucoma with choroidal and retinal detachment. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1993;2(1):61-2. 19. Dey M, Situnayake D, Sgouros S, Stavrou P. Bilateral exudative retinal detachment in a child with orbital pseudotumor. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2007;44(3):183-6. 20. Yuen KS, Lai CH, Chan WM, Lam DS. Bilateral exudative retinal detachments as the presenting features of idiopathic orbital inflammation. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33(6):671-4. |