|

A 42-year-old woman presented with a sudden, painless loss of vision in her left eye of three days duration. It began as a mild dimming but rapidly dropped off. Her corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OS and 20/400 OS with no pinhole improvement. Her pupils were reactive to light and accommodation with a mild (grade 1) relative afferent defect OS. Confrontation visual fields were full in each eye and there was a central scotoma present on Amsler grid. Biomicroscopy was normal in each eye and her intraocular pressure was 18mm Hg OD and 19mm Hg OS.

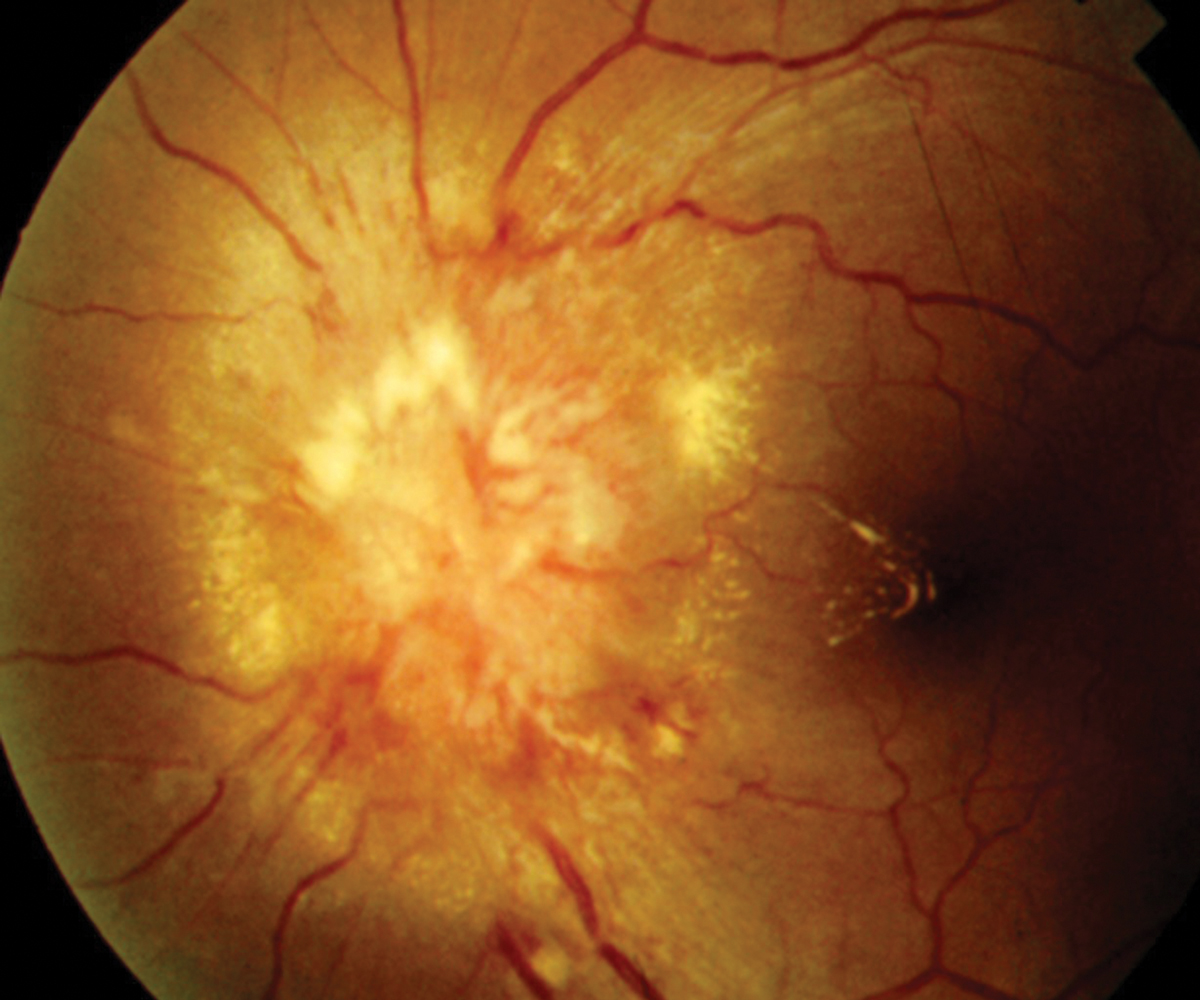

Funduscopic examination was normal in her right eye, but there was a prominently swollen optic disc with associated macular star of exudates in her left eye. She was specifically questioned about her health history and any recent changes. She denied any risk factors for HIV infection and was otherwise healthy with no diagnosed medical conditions. She reported no other neurological signs or symptoms.

When specifically asked, she did report a bad flu-like illness with lymphadenopathy about three weeks before (This occurred prior to COVID-19, so that was not a consideration). She spent no significant time outdoors and did not live in a Lyme disease-endemic area. She could not recall any animal scratches or tick or flea bites, but she did volunteer at an animal shelter.

Given the appearance and history, she was medically evaluated for syphilis, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, HIV and connective tissue disorders, all of which came back normal. She did test positive for high titers of Bartonella henselae, which confirmed the diagnosis of infectious optic neuropathy, specifically benign lymphoreticulosis, better known as cat scratch disease neuroretinitis.

Sources of Great Vision Loss

Neuroretinitis typically presents as a unilateral (rarely bilateral), acute, painless loss of vision. It rarely presents without vision loss. Acuity may be as low as finger-counting level.1-6 The typical visual field loss is a central or cecocentral scotoma.2

A funduscopy will reveal a markedly edematous disc. There may also be peripapillary hemorrhages due to venous stagnation. Occasionally, there will be a mild vitritis overlying the disc. Initially, there will be a serous retinal detachment extending from the disc to the macula.

The key diagnostic feature in well-developed neuroretinitis is the presence of macular exudates in the form of a macular star.1-6 However, this finding may not occur for up to several weeks after onset of visual symptoms, making the diagnosis more challenging. The serous retinal detachment within the posterior pole in association with disc edema is highly suspicious for early neuroretinitis with the macular exudates ensuing later.1

Numerous conditions have been seen in association with neuroretinitis including toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, measles, syphilis, Lyme disease, herpes simplex and zoster, mumps, tuberculosis, malignant hypertension, ischemic optic neuropathy and leptospirosis.7-14 However, the most common cause by far is Bartonella henselae; the organism responsible for cat scratch disease.1,3,14 Occasionally, cat scratch disease will be caused by B. quintana.15

In cat scratch disease neuroretinitis, there may be an antecedent history of fever, malaise and/or lymphadenopathy occurring several weeks preceding the visual loss. There may also be an antecedent history of a cat scratch or flea bite.16,17

As neuroretinitis is primarily due to infectious etiologies, it is likely that cell invasion with proinflammatory activation and suppression of apoptosis occurs.18 Visual loss is predominately more from the retinal edema rather than optic nerve dysfunction. This is evidenced by the fact that the visual field defects reflect a retinal cause as well as the relative mild degree (or absence) of an afferent pupil defect in the face of profound vision loss.2,14

After development of the disc and retinal edema, there will be spontaneous resolution and fluid resorption. The aqueous phase of the edema resolves the fastest, leaving the accumulated lipid exudates within the outer plexiform layer, forming the characteristic macular star.19

|

|

Neuroretinitis from cat scratch disease is typically a self-limiting condition with an excellent prognosis. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis and Treatment

When encountering neuroretinitis, medically consider and evaluate patients for all possible infectious causes and do not immediately default to cat scratch disease. A history should be elicited for exposure to cats, flea and tick bites, travel to Lyme-endemic areas, exposure to sexually transmitted disease, lymphadenopathy, skin rashes, malaise, myalgia and fever. As dictated by the history, order the following tests: Lyme titer, toxoplasmosis titer, toxocariasis titer, purified protein derivative skin testing, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, reactive plasma reagin and chest x-ray for tuberculosis. The most common cause is infection by B. henselae or B. quintana from a cat scratch.20

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) may be a valuable adjunctive diagnostic test. Subretinal fluid not visible on clinical examination or fluorescein angiography may be readily identified with OCT, making it an adjunctive imaging tool in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with cat scratch-related neuroretinitis.21,22

When encountering neuroretinitis or any presumed infectious optic neuropathy, targeted antimicrobial agents should be instituted in cases due to specific etiologies (e.g., syphilis, Lyme disease, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis). Neuroretinitis from cat scratch disease is typically a self-limiting condition with an excellent prognosis. Most patients will have a return to normal or near normal vision without treatment. Antimicrobial therapy may be used to hasten recovery. Successful oral agents include rifampin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim.23,24

A commonly used therapy is doxycycline 100mg PO BID for two to four weeks.23,24 Alternately, azithromycin 250mg to 500mg PO BID for two to four weeks may be used. Frankly, the absence of controlled clinical studies and lack of consensus makes pretty much every standard course of oral antibiotics a possible therapy.

Oral steroids may also be used to mitigate inflammation.25,26 Intravitreal injection of Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech) has been shown to improve both visual acuity as well as decrease macular edema.25 However, the overall good prognosis of neuroretinitis may not justify this treatment, especially since this information comes from case reports and not from controlled clinical trials. Those who are immunocompromised should be given strong consideration for antibiotic treatment.

For the patient presented here, her poor vision and anxiety made for the choice to initiate a four-week course of doxycycline 100mg BID PO. When she missed her scheduled two-week follow up appointment, she was called and, over the phone, she stated that she recently stopped taking the medication because it upset her stomach. Her vision was improving, though there was no way to quantify. She was offered a different antibiotic, but declined. She was reappointed for one week but was lost to follow-up after the phone call.

Takeaways

When encountering neuroretinitis from suspected cat scratch disease, it may help to remember this rhyme: “When the vision loss great and the APD mild, it’s often the bite of something wild.”

Dr. Sowka is an attending optometric physician at Center for Sight in Sarasota, FL, where he focuses on glaucoma management and neuro-ophthalmic disease. He is a consultant and advisory board member for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Bausch Health.

1. Wade NK, Levi L, Jones MR, et al. Optic disk edema associated with peripapillary serous retinal detachment: an early sign of systemic Bartonella henselae infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(3):327-34. 2. Ghauri RR, Lee AG. Optic disk edema with a macular star. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43(3):270-4. 3. Suhler EB, Lauer AK, Rosenbaum JT. Prevalence of serologic evidence of cat scratch disease in patients with neuroretinitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(5):871-6. 4. Pérez G J, Munita S JM, Araos B R, et al. Cat scratch disease associated neuroretinitis: clinical report and review of the literature. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2010;27(5):417-22. 5. Biancardi AL, Curi AL. Cat-scratch disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(2):148-54. 6. Ksiaa I, Abroug N, Mahmoud A, et al. Update on Bartonella neuroretinitis. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):254-61. 7. Moreno RJ, Weisman J, Waller S. Neuroretinitis: an unusual presentation of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmologie. 1980;215:53-8. 8. Arruga J, Valentines J, Mauri F, et al. Neuroretinitis in acquired syphilis. Doc Ophthalmol. 1986;64:23-9. 9. Karma A, Stenborg T, Summanen P, et al. Long-term follow-up of chronic Lyme neuroretinitis. Retina. 1996; 16(6):505-9. 10. Margo CE, Sedwick LA, Rubin ML. Neuroretinitis in presumed visceral larva migrans. Retina. 1986;6(2);95-8. 11. Neppert B. Measels retinitis in an immunocompetent child. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1994;205:156-60. 12. Foster RE, Lowder CY, Meisler DM, et al. Mumps neuroretinitis in an adolescent. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(1):91-3. 13. Stechschulte SU, Kim RY, Cunningham ET Jr. Tuberculous neuroretinitis. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 1999;19(3):201-4. 14. Donnio A, Buestel C, Ventura E, et al. Cat-scratch disease neuroretinitis. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2004;27(3):285-90. 15. George JG, Bradley JC, Kimbrough RC, et al. Bartonella quintana associated neuroretinitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(2):127-8. 16. Brazis PW, Stokes HR, Ervin FR. Optic neuritis in cat scratch disease. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1986;6(3):172-4. 17. Chrousos GA, Drack AV, Young M, et al. Neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1990;10(2):92-4. 18. Dehio C. Molecular and cellular basis of bartonella pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:365-90. 19. Matsuo T, Kato M. Submacular exudates with serous retinal detachment caused by cat scratch disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2002;10(2):147-50. 20. Flexman JP, Chen SC, Dickeson DJ, et al. Detection of antibodies to Bartonella henselae in clinically diagnosed cat scratch disease. Med J Aust. 1997;166(10):532-5. 21. Habot-Wilner Z, Zur D, Goldstein M, et al. Macular findings on optical coherence tomography in cat-scratch disease neuroretinitis. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(8):1064-8. 22. Cruzado-Sánchez D, Tobón C, Lujan V, et al. Neuroretinitis caused by Bartonella henselae: a case with follow up through optical coherence tomography. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2013;30(1):133-6. 23. Rosen B. Management of B. henselae neuroretinitis in cat-scratch disease. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(1):1-2. 24. Rosen BS, Barry CJ, Nicoll AM, et al. Conservative management of documented neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease associated with Bartonella henselae infection. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1999;27(2):153-6. 25. Cakir M, Cekiç O, Bozkurt E, et al. Combined intravitreal bevacizumab and triamcinolone acetonide injection for idiopathic neuroretinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17(3):221-3. 26. Fairbanks AM, Starr MR, Chen JJ, Bhatti MT. Treatment strategies for neuroretinitis: current options and emerging therapies. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(8):36. |