Vision CareCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: - Kids and Screens: Debating the Dangers |

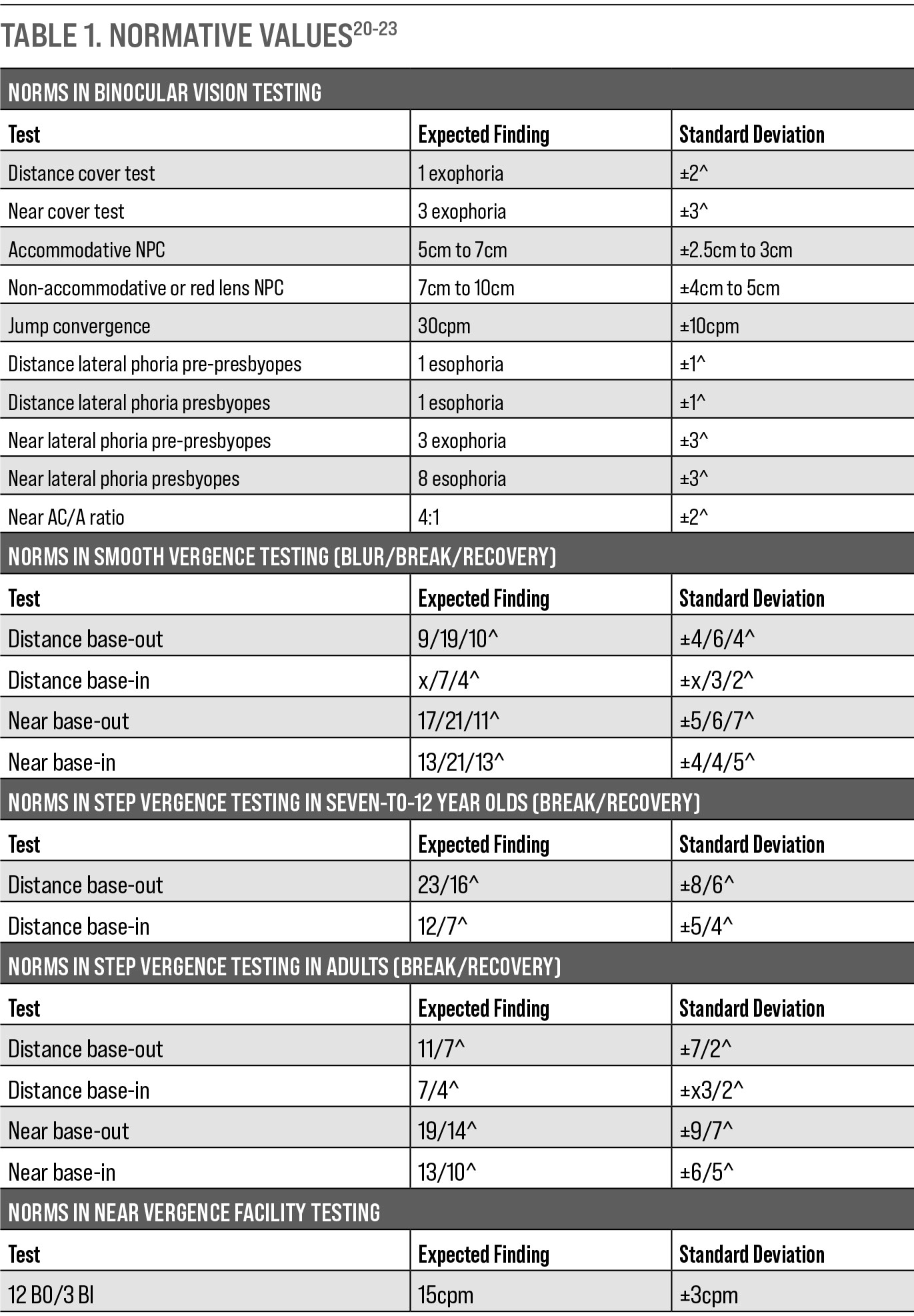

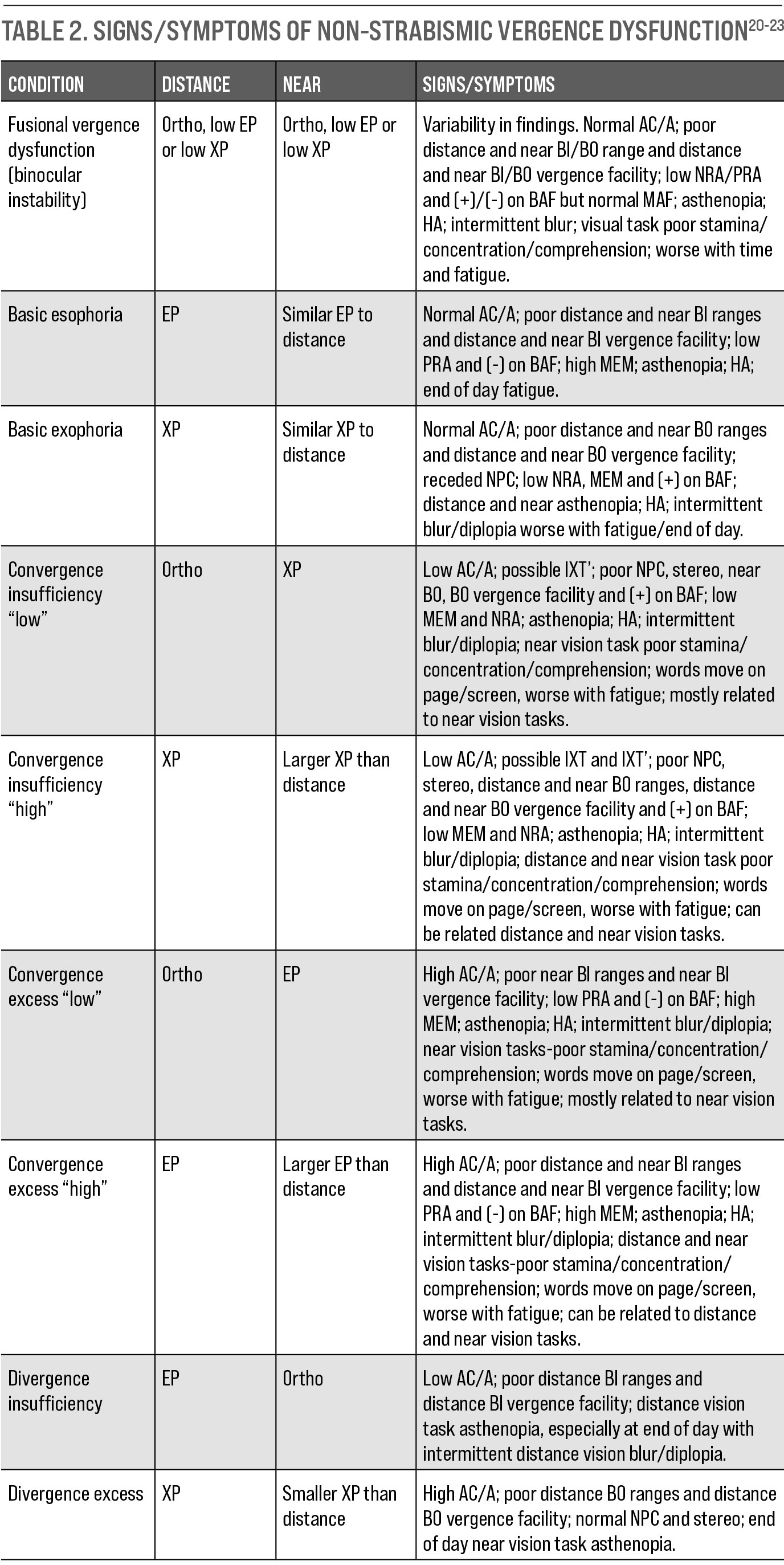

Binocular vision disorders are prevalent in patients at all stages of life—from pediatric to geriatric—and especially in patients with developmental disabilities and a history of traumatic brain injury.1-10 They can significantly affect a patient’s quality of life and their ability to perform daily tasks.11-19 Given the prevalence and symptomatology, all practitioners, regardless of their clinical settings, should be well adept at binocular vision testing and understand what is considered normal—and what suggests a binocular vision dysfunction (Tables 1 and 2).20-23

These tips and tricks can help you avoid some of the common pitfalls of a binocularity evaluation. The accompanying charts are designed as quick references to help you better care for patients with binocular vision dysfunction.

|

| Measure the magnitude of a strabismus when performing a near cover test with an accommodative letter target. Click image to enlarge. |

Ask the Right Questions

People, especially children, don’t usually spend their free time talking or thinking about their eyes and visual experiences. A child with a visual dysfunction likely doesn’t know that their visual experiences—such as diplopia, asthenopia, frontal headache, getting lost in the page or difficulty understanding what they read—are not normal.

I can’t tell you how many patients I have seen for their first eye exam who have a binocularity dysfunction without even knowing it. When questioned, these patients often admit that they had a lot of difficulty getting through school and the issues persist at their job, especially when near work and computer use is involved. As kids, they either struggled through it, found accommodations (such as leaning their face on one hand and effectively occluding an eye while reading, making them monocular), or avoided near vision tasks all together. Optometrists should always ask the right questions to discover these symptoms, because no one else in the patient’s life might do so.

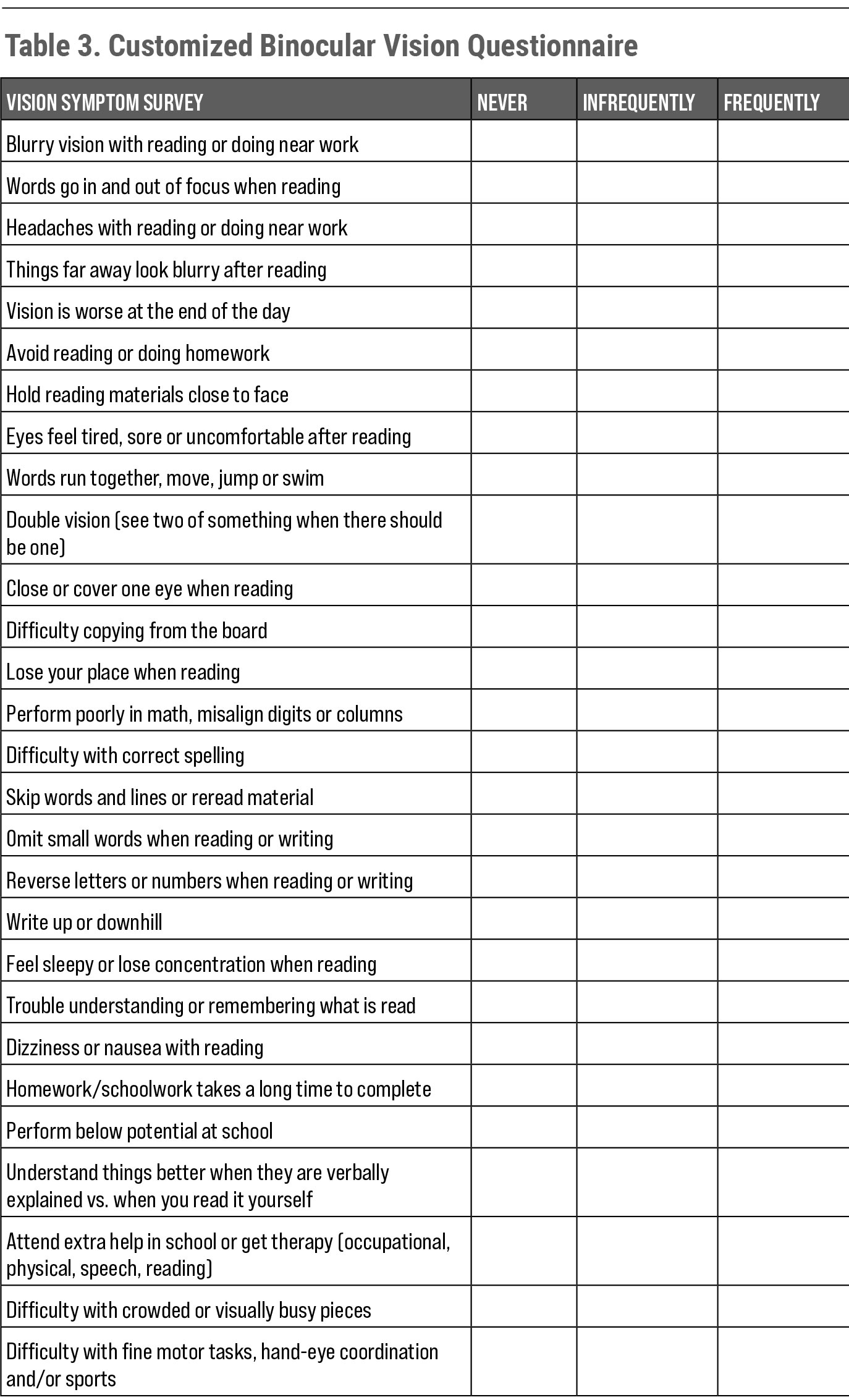

Clinicians can use a standardized questionnaire24-27 (such as the readily available Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey or Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey) or create a customized questionnaire (Table 3). I find it is best to provide symptom surveys prior to a patient’s visit (via email or a website) to save in-office time and ensure each patient is properly screened for signs and symptoms of binocular dysfunction.

Don’t Ignore Symptoms

If a patient reports symptoms but the exam elicits no corresponding signs, consider these testing pitfalls:

Stamina. A patient who normally spends the day performing strenuous vision tasks may present on a good day after a restful night’s sleep and before they participate in any strenuous work; thus, the initial findings may appear deceivingly normal. Repeating some of the binocularity and accommodative testing, performing a test several times or rescheduling the patient for another appointment at the end of the day can help to elicit an underlying binocularity problem.28-30

Targets. Use proper accommodative and non-accommodative targets for testing, and understand the difference between the two.

Speed. The binocular and accommodative systems must have time to respond to changes. Performing a cover test too fast or moving the targets too fast in testing such as NPC and vergence ranges can result in inaccurate responses and findings.

Onset and comitancy. Acute onset and non-comitant deviations should prompt a careful consideration of whether the strabismus has a pathologic etiology. This is also true of longstanding deviations that are progressing or not responding well to treatment.31

|

| Perform near point of convergence testing with a non-accommodative light target and a light lens. Click image to enlarge. |

Don’t Forget Direct Observation and Stereopsis

If strabismus is suspected or reported, the practitioner should first observe if the strabismus is present while the patient is in their habitual state. If it is, you will need to make a few more observations about cosmesis, direction, laterality, frequency, magnitude and comitancy. Also note if the patient has abnormal head posture (head turn, tilt or tip), nystagmus, anisocoria, ptosis, facial asymmetry or epicanthal folds.

In cases where a binocular vision dysfunction is reported, suspected or evident, I like to assess the patient’s binocularity before occluding either eye. Once an eye is occluded, breaking down binocularity, you may not be able to evaluate a patient’s performance under their natural viewing conditions, especially in patients with a fragile binocular system. This is especially useful on follow-up evaluations where an optimal vision correction has already been prescribed. Improvement in stereopsis through an add can be an additional piece of clinical information when considering a potential near correction. Repeating stereo testing after finishing the visual analysis and before dilation can also help assess the stability and stamina of the patient’s binocular system. I’ve found that if the patient can achieve the same stereoacuity before and after a visual evaluation (before dilation), it is a favorable sign that the patient has a stable and resilient binocular system.

|

| Table. 1. Normative Values. Click table to enlarge. |

Focus on the Near Point of Convergence

The near point of convergence (NPC) subjectively evaluates the ability to comfortably, efficiently and binocularly converge one’s eyes to a punctum proximum of convergence.27,32-37 While an important test, it can be fraught with mistakes, including: not having the patient wear their habitual near prescription during testing, not using an appropriate target, moving the target too quickly toward the patient, not keeping the target about 20º below eye level while testing, not watching the patient’s eyes during the test and not performing the release and regrasp portion of the test. Taking care with this evaluation may be an inconvenience at first, but getting the hang of it will pay off in a practitioner’s assessments and provide the best results.

The practitioner must observe the patient’s eyes during testing; if the patient loses fusion but is suppressing, they will not report diplopia, but one of their eyes will deviate due to loss of fusion. The point of subjective diplopia or objective loss of fusion is considered the break. Once the NPC break is reached, the practitioner slowly pulls the target away to find the NPC recovery where the patient subjectively reports single vision or an objective observation of realignment is made.

Many providers stop the test at this point, but there are other useful components. Once the recovery is determined, move the target one inch further from the patient and have the patient look at the target for three seconds, then at a distance target for three seconds and back at the near target again. Through this series, the practitioner should be observing six components other than break and recovery of NPC:

- Reach: can the patient direct their eyes to locate the target.

- Grasp: can the patient sustain visual attention and alignment on the target as it moves closer.

- Release: can the patient let go of fusion and direct their eyes from the NPC to a more distant point.

- Regrasp: can the patient direct their eyes from a distant point back to the NPC.

- Jump convergence: does the patient have a good facility and stamina of jumping from a distant target to the NPC for a length of time.

- Manipulation: if the patient is having difficulty, can they converge better when manually touching the target. Note any head movement, grimacing, motor overflow or other symptoms.

Because convergence is a team effort between fusional vergence (binocularity) and accommodative vergence (accommodation), it is helpful to identify which system is performing poorly—and that requires carefully chosen targets. When using an accommodative target—in patients with 20/20 BCVA, 20/30 near Snellen letters, Lea symbols or small pictures with various colors and small details—both fusional and accommodative vergence are being evaluated. Make sure the patient is attending the target and keeping it clear. Non-accommodative targets, such as a transilluminator or pen tip, only stimulate fusional convergence.

Since under-accommodation does not encourage accommodative convergence, repeating the NPC with each kind of target can help differentiate fusion vergence (convergence insufficiency) from accommodative vergence (pseudo-convergence insufficiency) dysfunction.

A pseudo-convergence insufficiency occurs if an accommodative dysfunction inhibits vergence. To further identify a pseudo-convergence insufficiency, place a +0.75D lens OU on top of the habitual near prescription and repeat the NPC. If accommodation is inhibiting vergence, the add lens will relax accommodation and allow the NPC to improve.

If the NPC improves with the +0.75D lenses, this points to a combined binocular and accommodative dysfunction, while a lack of NPC improvement points to a predominantly binocular dysfunction.

Using a red lens or red/green glasses on top of the habitual near prescription to repeat the NPC can allow a more in-depth evaluation of the control the patient has over their binocular system. The color filters dissociate the images between the two eyes, requiring more control of motor fusion to keep the eyes aligned and the two targets fused. If the red lens NPC is normal (usually reduced by 1cm to 2cm compared with a normal NPC), that signifies a healthy vergence system.

|

| Table 2. Signs/Symptoms of Non-Strabismic Vergence Dysfunction. Click table to enlarge. |

Measure, Don’t Guess, the Magnitude

It takes a lot of practice to accurately approximate the magnitude of an ocular deviation, and it should be avoided when possible. This is especially true in a setting where a patient may be followed by various providers, as each one may have their own norm for estimating a deviation.

The magnitude of the deviation can be measured during cover testing and with other free-space binocular posture evaluations (e.g., Maddox rod with prism bar, modified Thorington test card, Brock posture board). When neutralizing and measuring the deviation, the base of the prism should be placed in the same direction as the eye movement on cover testing (base-out prism will neutralize an eso, and base-in will neutralize an exo deviation).

Prism bars or loose prisms should be added until no movement is seen on cover testing or the patient reports an orthophoria position on the binocular posture test. With prism bars, position the flat end of the bar flat on the patient’s face so it is touching the eyebrow, the patient looks through the center of the prism, with the bar perpendicular to the fixation object.32-38

For near fixation targets, angle the bar slightly inward so that it is perpendicular to the fixation when the patient is converging. If you want to become more versed at approximating an ocular deviation, first approximate and then measure the deviation until your approximations consistently correspond with the measurement. This may take years to perfect, and even then, measurement is preferable when possible.

|

| Perform NPC with an accommodative letter target and +0.75D OU lenses. Click image to enlarge. |

Perform Proper Cover Tests

A unilateral cover test (UCT) differentiates a hetereophoria from a heterotropia, and an alternating cover test (ACT) measures the magnitude of deviation consisting of both the phoria and the tropia.32-38 If a tropia is present, the UCT determines the direction, frequency, laterality and magnitude of the tropia. A frosted occluder may be preferable because you can see what is happening behind the occluder.

During distance evaluation, the patient must be fixating a distance target, which may require you to use the hallway if you have a short exam lane. During near cover testing, have the patient read out the letters or describe the different characteristics of a target on a fixation stick to ensure they are properly attending and accommodating. Otherwise, accommodative convergence will not be stimulated and an exo deviation may be overestimated or an eso deviation underestimated.

If there is an observable unilateral strabismus, first occlude the non-deviated eye on UCT to see if the strabismic eye will take up fixation. Perform the test slowly for at least 20 to 30 seconds. Cover an eye for three to five seconds and then uncover it for another three to five seconds to allow time for the binocularity to dissociate when one eye is covered and then for the eyes to fixate when both eyes are uncovered. If you move through the test too quickly, you can miss a phoria that breaks down into a tropia or a tropia that increases in magnitude over time.

If a tropia is discovered, use a neutralizing prism to measure the deviation and then perform the ACT. Again, move through the test slowly with sufficient time covering an eye (two to three seconds) before quickly moving the paddle to the other eye.

|

| Table 3. Customized Binocular Vision Questionnaire. Click table to enlarge. |

Amblyopia Isn’t a One-eye Problem

Amblyopia is defined as a bilateral or unilateral BCVA of less than 20/20 in the absence of structural or pathological anomalies and in the presence of one or more amblyogenic factor before the age of eight:39, 40

- Constant unilateral esotropia or exotropia.

- Anisometropia.

- Bilateral isometropia or unilateral/bilateral astigmatism of amblyogenic amount.

- Stimulus deprivation or image degradation.

Input from the two eyes is segregated into alternating strips in the primary visual cortex (V1), and the cortical layers above and below V1 consist of columns that respond to specific characteristics of an image. The ocular dominance columns compare input from the two eyes by responding more to one eye than the other or equally to both.

Formation of these ocular dominance columns relies both on axon guidance cues (nature) and spontaneous retinal activity (nurture) and can be modified in response to visual experience during the critical period (the first eight years).

Monocular deprivation (blur or strabismus) during the critical period results in a pronounced decrease in the area of V1 representing the deprived eye and a corresponding increase in representation of the sound eye, making amblyopia a “lazy brain” not a “lazy eye” problem.

When the visual system experiences amblyogenic factors such as vision blur or strabismus, it responds with a progressive reduction of visual acuity, which continues to deteriorate until the end of the critical period. Aside from the visual acuity decrease, associated deficits can be found in both the amblyopic and non-amblyopic eyes, including visual perceptual dysfunction, increased sensitivity to crowding, spatial distortions, reduced contrast sensitivity, unsteady monocular fixation, inaccurate accommodative response and poor oculomotor function.

Amblyopia is not a one-eyed problem; the issue is in the conflict between the two eyes taking place in the brain. Penalization and monocular occlusion allows for improvement in the BCVA but does not allow for integration and binocularity in the brain, potentially allowing for more regression after treatment.

Treat or Refer?

Every patient, especially one that is symptomatic, deserves a full visual function evaluation and treatment. If you are unable to provide this evaluation or you can make the diagnosis but cannot treat it, comanage the patient with a behavioral optometrist trained in vision therapy and rehabilitation.

Providers will find that many offices that provide vision rehabilitation do not have an optical and do not provide comprehensive vision services. Opening a dialogue with colleagues to properly comanage patients can help increase patient satisfaction and retention as well as identify a new referral source for the office.41-43

You can write a letter to the comanaging clinician requesting the patient return to your optical if their spectacle or contact lens prescription changes or if the patient needs an ocular health evaluation; this can help alleviate any confusion between comanaging providers.

Organizations such as the College of Optometrists in Vision Development (covd.org), Optometric Extension Program Foundation (oepf.org) and American Optometric Association (aoa.org) have doctor locators by proximity, which can aid in finding a referral source as well as courses for those interested in learning more about binocular vision.

Dr. Petrosyan is an associate clinical professor at SUNY College of Optometry and East New York Diagnostic and Treatment Center. She has financial interest in Anteo Health, where she is a partner and the head of vision therapy. Dr. Petrosyan is a consultant for the Armenian Eye Care Project (no financial interest).

| 1. Porcar E, Martinez-Palomera A. Prevalence of general binocular dysfunctions in a population of university students. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:111-3. 2. Lara F, Cacho P, Garcia A, Megias R. General binocular disorders: prevalence in a clinic population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2001;21:70-4. 3. Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. Accommodative insufficiency is the primary source of symptoms in children diagnosed with convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:857-8. 4. Rouse MW, Borsting E, Hyman L, et al; Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) group. Frequency of convergence insufficiency among fifth and sixth graders. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:643-9. 5. Letourneau JE, Ducic S. Prevalence of convergence insufficiency among school children. Can J Optom. 1988;50:194-7. 6. Porcar E, Martinez-Palomera A. Prevalence of general binocular dysfunctions in a population of university students. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:111-3. 7. Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ. Vision disturbances following traumatic brain Injury. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2002;4:271–80. 8. al-Qurainy IA. Convergence insufficiency and failure of accommodation following midfacial trauma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:71–5. 9. Cockerham GC, Goodrich GL, Weichel ED, et al. Eye and visual function in traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:811-8. 10. Rosner J, Rosner J. Comparison of visual characteristics in children with and without learning difficulties. Am J Optom Physiol. 1987;64(7):531–533. 11. Maples WC. Visual factors that significantly impact academic performance. Optometry. 2003;74:35-49. 12. Borsting E, Rouse MW, Deland PN, et al. Association of symptoms and convergence and accommodative insufficiency in school-age children. Optometry. 2003;74:25-34. 13. Grisham D, Powers M. Visual skills of poor readers in high school. Optometry. 2007;78(10):542-9. 14. Dusek W, Pierscionek BK, McClelland JF. A survey of visual function in an Austrian population of school-age children with reading and writing difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010;10:16. 15. Letourneau JE, Lapierre N, Lamont A. The relationship between convergence insufficiency and school achievement. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1979;56:18–22. 16. Scheiman M, Rouse M, Kulp MT, et al. Treatment of convergence insufficiency in childhood: a current perspective. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:420-8. 17. Rouse MW, Borsting EJ, Mitchell GL, et al. Academic behaviors in children with convergence insufficiency with and without parent-reported ADHD. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:1169-77. 18. Mojon-Azzi SM, Kunz A, Mojon DS. Strabismus and discrimination in children: are children with strabismus invited to fewer birthday parties? Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:473-76. 19. Davidson S, Quinn GE. The impact of pediatric vision disorders in adulthood. Pediatrics. 2011;127:334-39. 20. AOA Evidence-Based Optometry Guideline Development Group. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline: care of the patient with amblyopia. American Optometric Association. 2004. 21. Martinez CP, Munoz GA, Ruiz-Cantero MT. Treatment of accommodative and nonstrabismic binocular dysfunctions: a systematic review. Optometry. 2009;80:702-16. 22. Gallaway M, Scheiman M, Mitchell L. Vision therapy for post-concussion vision disorders. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(1):68-73. 23. Hoffman LG, Rouse M. Referral recommendations for binocular function and/or developmental perceptual deficiencies. J Am Optom Assoc. 1980;51:119-26. 24. AOA Evidence-Based Optometry Guideline Development Group. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline: care of the patient with accommodative and vergence dysfunction. American Optometric Association. December 2010. 25. Hayes GJ, Cohen BE, Rouse MW, De Land PN. Normative values for the nearpoint of convergence of elementary schoolchildren. Optom Vis Sci. 1998;75:506-12. 26. Hughes A. AC/A ratio. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967;51:786-7. 27. AOA Evidence-Based Optometry Guideline Development Group. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline: comprehensive pediatric eye and vision examination. American Optometric Association. February 12, 2017. 28. Rouse MW, Borsting EJ, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:384-90. 29. Borsting E, Rouse M, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in children aged 9 to 18 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:832-38. 30. Laukkanen H, Scheiman M, Hayes JR. Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS) Questionnaire. Optometry and Vision Science. 2017;9(1):43-50. 31. Weimer A, Jensen C, et al. Test-retest reliability of the brain injury vision symptom survey. Vision Dev & Rehab. 2018;4(4):177-85. 32. Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical management of binocular vision. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2014. 33. Berens C, Stark E. Studies in ocular fatigue. IV. Fatigue of accommodation, experimental and clinical observations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1932;15:527-42. 34. Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of vision therapy/orthoptics versus pencil pushups for the treatment of convergence insufficiency in young adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:583-95. 35. Hoyt C, Good W. Acute onset concomitant esotropia: when is it a sign of serious neurological disease? Br J Ophthalmol.1995;79 498-501. 36. Scheiman M, Gallaway M, Frantz KA, Peters RJ, Hatch S, Cuff M, Mitchell GL. Nearpoint of convergence: test procedure, target selection, and normative data. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80(3):214-25. 37. Griffin J, Grisham D. Binocular Anomalies: Diagnosis and Vision Therapy. 4th Ed. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002. 38. Taub MB, Rowe S, Bartuccio M. Examining special populations. Part 3: examination techniques. Rev Optom. 2006;144(3):49-52. 39. Press L. Applied Concepts in Vision Therapy. Optometric Extension Program Foundation; 2008. 40. Birnbaum M. Optometric Management of Nearpoint Vision Disorders. Optometric Extension Program Foundation; 2008. 41. Weddell L. Investigative techniques in binocular vision. www.optometry.co.uk/uploads/articles/cetarticle_2611.pdf. 2010. Accessed October 2, 2020. 42. Irsch K. Optical issues in measuring strabismus. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(3):265-70. 43. The Lasker/IRRF Initiative for Innovation in Vision Science. Amblyopia: challenges and opportunities. www.laskerfoundation.org/media/filer_public/20/0a/200a94fb-8e5b-4491-9bec-6bbc244e03fa/2017_amblyopia_report.pdf. March 2017. Accessed October 12, 2020. |