|

A 71-year-old man was referred from the local hospital after a 125-pound cement truck tire exploded while he was attempting a repair at his tire shop. The explosion catapulted the patient 10 to 15 yards in the air before he landed on cement and lost consciousness. The patient was airlifted to the local hospital due to life-threatening injuries, including a sternum fracture, left ulna fracture, traumatic brain injury and numerous foreign bodies embedded in his chest, face and eyes. The patient was hospitalized for three days, during which he complained of severe eye pain, light sensitivity and reduced vision in both eyes. He was given erythromycin ointment to be used once daily OU by the attending hospital staff. An eye examination was never completed while the patient was admitted.

Examination

One-week post-accident, the patient presented complaining of eye pain OS>OD and blurry vision. He stated that the erythromycin ointment was not helpful but that his eyes did feel better.

The patient’s entering visual acuities were 20/30 OD and 20/25 OS uncorrected. His pupils were equal and round without an afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressures were 13mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS. During testing, the patient was extremely photophobic. A drop of proparacaine was instilled OU to help with pain control.

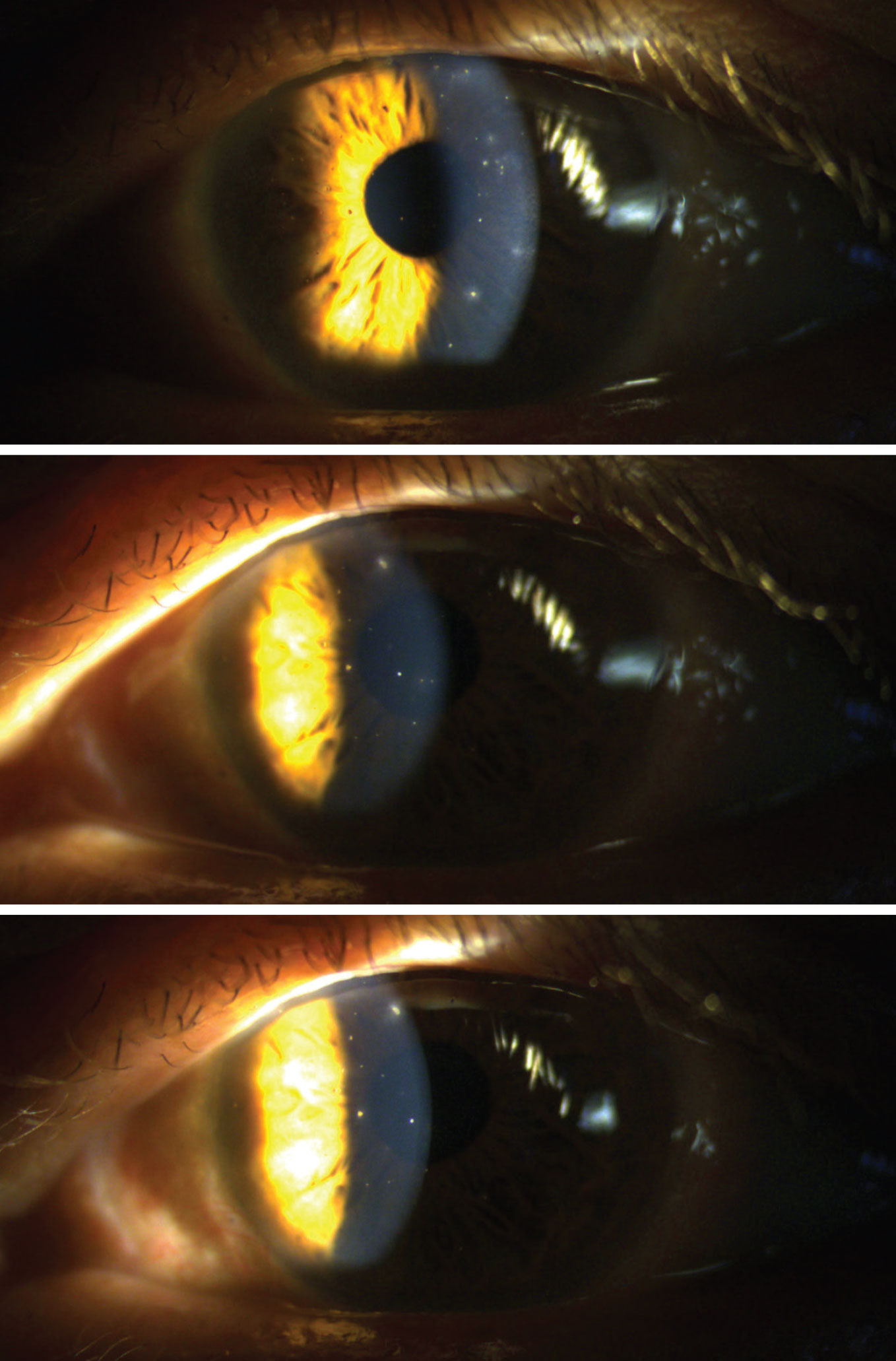

Upon anterior segment evaluation, the eyelids were noted to have mild edema of the superior lids. There were numerous embedded bulbar conjunctival foreign bodies, and the conjunctiva was diffusely injected 360°. No foreign bodies were noted in the palpebral conjunctiva. The cornea showed trace edema OD>OS, and numerous corneal foreign bodies of differing material were noted OU, OS>OD. Some foreign bodies were embedded past Bowman’s membrane, and some were superficial. None of the foreign bodies were embedded past the posterior stroma/Descemet’s membrane, nor were any full stromal thickness. There was no apparent iris or lens damage. The foreign bodies were only present in the exposed tissues within the palpebral aperture due to the explosive force embedding the foreign bodies before a blink could occur.

The patient was extremely symptomatic due to hundreds of open corneal epithelial wounds as a result of foreign bodies that were beginning to move anteriorly. Some had already fallen out on their own, which was apparent due to positive sodium fluorescein staining over abrasions without any foreign bodies present.

The foreign bodies were of differing materials, including metallic, organic, glass and others of unknown origin, due to the various substances that originated from the tire tread. This encompassed everything that the tire had driven over and trapped in its tread.

All corneal defects were Seidel-negative OU and non-penetrating. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet OU. The iris was flat, even and intact OU. Upon dilation, no foreign bodies were noted in the posterior chamber.

An initial lavage with saline eye wash was done to remove any superficial foreign bodies OU. Once complete, a foreign body spud was used to remove all surface-level foreign bodies and an Alger brush with 5mm burr was used to remove rust rings where necessary OU.

|

|

Embedded corneal foreign bodies of differing material scattered throughout the left cornea. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Corneal foreign bodies are the second most common form of ocular trauma. Traditionally, they are superficial and can be very uncomfortable for the patient. Rarely, they may embed in and even penetrate the cornea.

These injuries commonly happen in the workplace and occur most frequently in occupations that involve metalwork. The best protection against corneal foreign bodies is protective eyewear, such as safety shields and goggles. Most workers do not wear eye protection consistently and, because of this, are at a much higher risk of serious ocular harm.1

In the unfortunate event that a foreign body makes its way into the cornea, the origin of the foreign body must first be determined. Removal should then happen as quickly as possible.

Removal can occur using many different techniques. Irrigation can remove superficial foreign material quite well and is less invasive than other methods. However, if the foreign body is deeply embedded, a 25- to 30-gauge beveled needle or a stainless steel spud can be used under slit lamp to assist in removal. While an Alger brush with burr can also be used to eradicate a foreign body, it is most frequently used to remove rust rings that are commonly the result of metallic foreign bodies.

Metallic foreign bodies can be removed with a low risk of infection; however, they have a higher risk of scarring after removal. If the abrasion post-foreign body removal is large or central in nature, it is common to issue topical prophylactic antibiotic coverage.

If a foreign body is organic in nature, risk of infection is higher, and the patient should be monitored closely for development of bacterial or fungal keratitis post-foreign body removal. It would also be appropriate to issue a topical broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotic in this case.

Patching has been shown to provide no improvement in healing time or pain control in those who have undergone foreign body removal and is therefore not a commonly used method.2

If a foreign body is posterior to the posterior stroma or Descemet’s membrane, or full stromal thickness, emergent surgical removal by an ophthalmologist is recommended.

Wrap-up

Once the foreign bodies that were able to be removed were taken care of, the patient was given one more saline lavage OU. Ofloxacin drops were issued for use QID OU for seven days. The patient was not patched, and, due to the small size of the patient’s corneal epithelial defects and residual embedded foreign bodies, a bandage contact lens was not placed.

Upon follow-up two days later, the patient’s symptoms were greatly reduced and his vision had begun improving. A few superficial foreign bodies were starting to emerge, so removal was assisted with a corneal foreign body spud.

At the final follow-up two days later, all remaining foreign bodies were deep in the corneal epithelium, and the cornea was smooth without sodium fluorescein staining. No additional abrasions were present. The patient was asymptomatic.

Since the final follow-up, the patient was seen two additional times. He remained without symptoms, and no further foreign body removal was necessary.

Dr. Lloyd is a board-certified medical optometrist who works at the Saint Cloud VA in Minnesota. She is co-chair of the Education Committee of the Armed Forces Optometric Society and co-chair of the VA National TBI Optometry Workgroup. She has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Mangan is a board-certified consultative optometrist from Boulder, CO, and a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. He is an assistant professor in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. His focus is on ocular disease and surgical comanagement. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Welch LS, Hunting KL, Mawudeku A. Injury surveillance in construction: eye injuries. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 2001;16(7):755-62. 2. Kaiser PK. A comparison of pressure patching versus no patching for corneal abrasions due to trauma or foreign body removal. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(12):1936-42. |