Retina on the RiseExperts offer pearls for detecting and managing numerous posterior segment conditions in the June 2023 issue of Review of Optometry, our 14th annual Retina Report. Featured articles cover everything from AMD staging, referral timing, interpreting vitreous opacities and using nutrition to promote retinal health. Check out the other articles featured in this issue:

|

A question I get asked daily at the end of an exam is, “Doc, what can I do for my eye health?” Although the obvious answer lies in overall lifestyle maintenance efforts such as diet and exercise, it is important to tailor these recommendations based on the patient’s unique ocular status. This step becomes increasingly crucial with the prevalence of eye diseases like age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy (DR).

As of 2019, about 13% of US adults over the age of 40 were diagnosed with AMD.1 It is the leading cause of blindness in adults over the age of 60 worldwide, with it affecting more than 190 million people in the global population as of 2020 and an estimated increase in prevalence to 288 million people by 2040.2 DR was estimated to affect 463 million people worldwide in 2020, with a projected increase in prevalence to 700 million by 2045, making it the leading cause of preventable blindness in working age adults.3

AMD is estimated to cost the global healthcare system more than $300 billion at this time, while the ADA found that diabetes alone cost the US healthcare system $327 billion in 2017.2,4 With the projected growth in prevalence of these diseases, the burden on the healthcare system will also continue to grow in the absence of preventative measures. The projected increase in prevalence correlates with the aging population, with age being a key risk factor in retinal disease and many other chronic health conditions.

Although aging is the result of multiple synergistic factors, a major factor is oxidative damage. The body releases reactive oxygen species during metabolism. A build-up of reactive oxygen species in cells can damage the DNA, RNA and proteins, eventually leading to cell death.5 The retina, being an extension of the central nervous system, has highly metabolic processes.6 Within the retina, the outer segments of the photoreceptors suffer from the most oxidative damage due to the process of phototransduction.7 If these proinflammatory pathways are not offset by compensatory antioxidants, then the cells undergo prolonged stress and, ultimately, death.5,8 The key to retinal neuroprotection may lay in promoting redox homeostasis to counteract the damaging effects of metabolism through dietary changes. Numerous studies have been conducted regarding the benefits of dietary supplements for eye health with a few notably consistent results.8,9 Below are the major supplements that have been shown to delay, or in some cases possibly reverse, retinal disease.

|

|

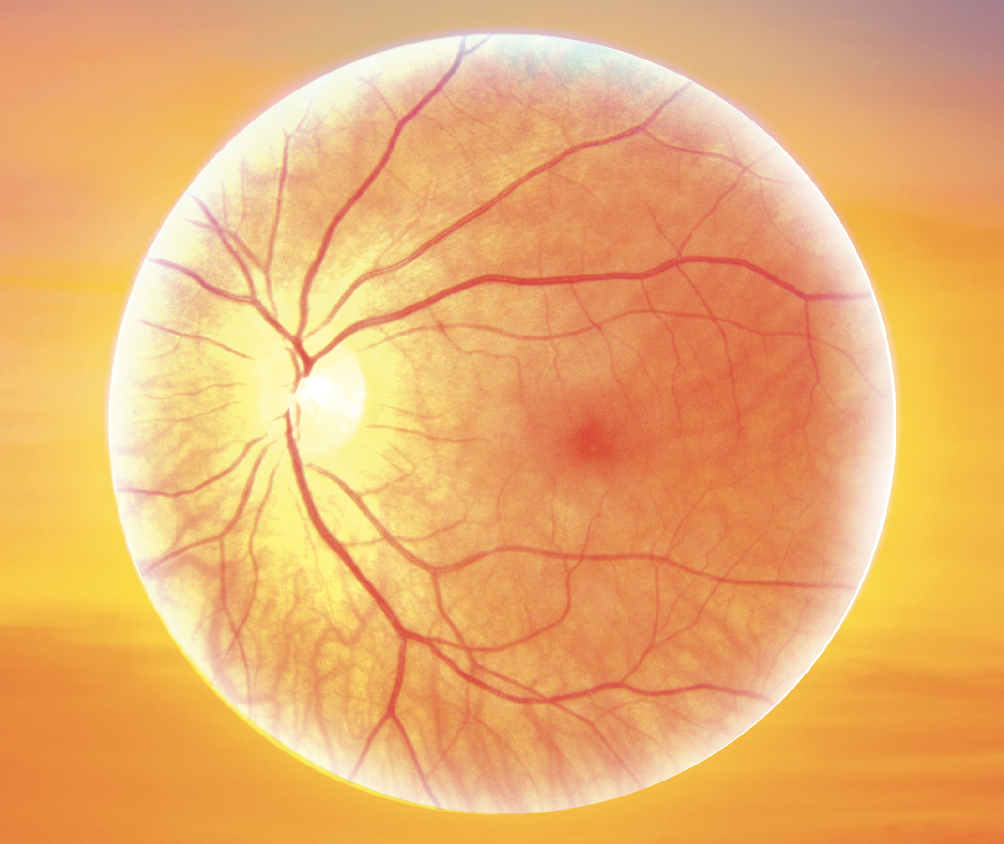

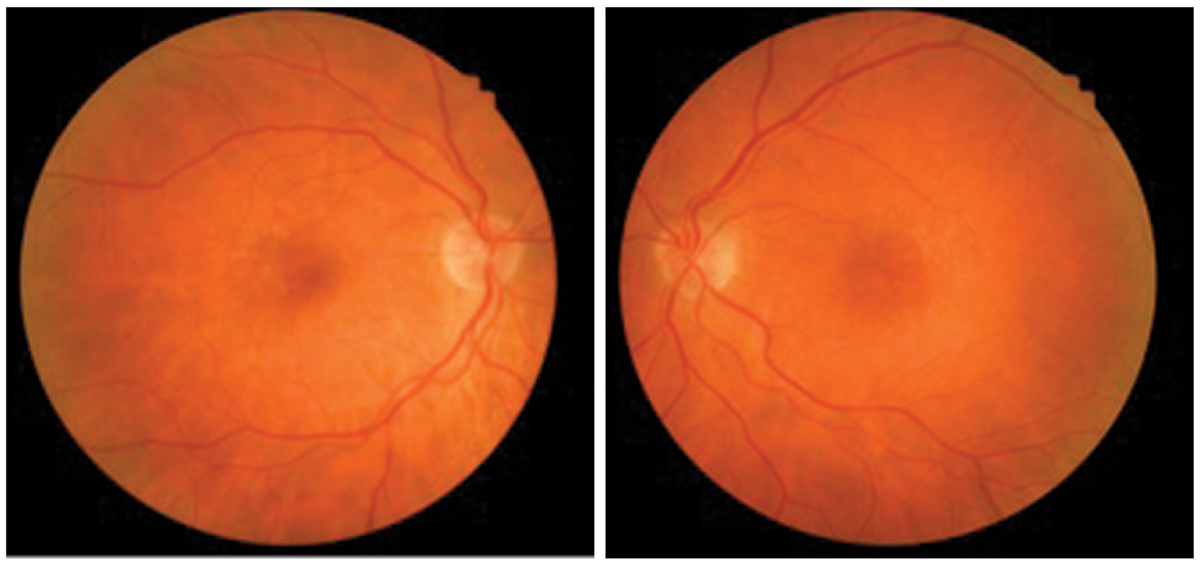

This patient was diagnosed with early dry AMD in both eyes. Photo: Amanda Legge, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Vitamins

These supplements appear to offer significant ocular benefits for patients. Bring this research up the next time patients ask for advice.

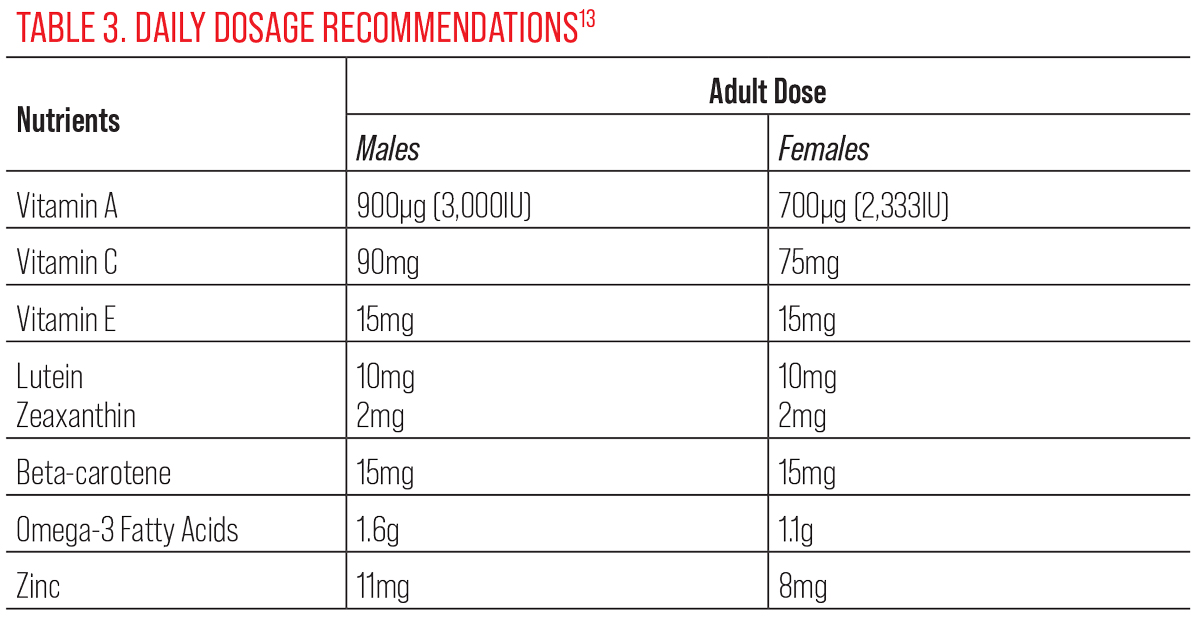

Vitamin A. This fat-soluble vitamin, in the form of 11-cis-retinal, is essential for normal phototransduction function in the retina.10 The recommended daily dose for children is 400µg to 500µg (about 1,500IU), adult men 900µg (3,000IU) and non-pregnant adult women 700µg (2,333IU).10 Low serum levels of vitamin A have been associated with nyctalopia, a condition that has been shown to be reversible with adequate supplementation, as well as Bitot’s spots on the conjunctiva.11

Vitamin A deficiencies affecting the retina can be monitored through fundus autofluorescence, in which a deficient patient would exhibit generalized hypoautofluoresence.10 Vitamin A supplementation in the form of retinyl palmitate has been shown to slow down the progression of retinitis pigmentosa at a dose of 15,000IU.12

In contrast, vitamin A supplementation has been shown to increase the risk of progression in Stargardt’s patients, so it should not be recommended in these cases.10 High-dose vitamin A supplementation is not recommended for routine patients due to the potential for toxicity, which can manifest as pseudotumor cerebri in the eyes.

Vitamin C. This water-soluble vitamin is the primary antioxidant in the eye, and it can be found in the lens, aqueous, vitreous and cornea.8 Dietary supplementation can be achieved in the forms of sodium ascorbate and ascorbic acid, although the former is not recommended for hypertensive patients due to the sodium content.

The recommended daily dose of vitamin C for adult males is 90mg and non-pregnant females is 75mg. Smokers need 35mg/day more than non-smokers.13 Ascorbic acid has been shown to suppress vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE), suggesting that it may be beneficial in DR.14

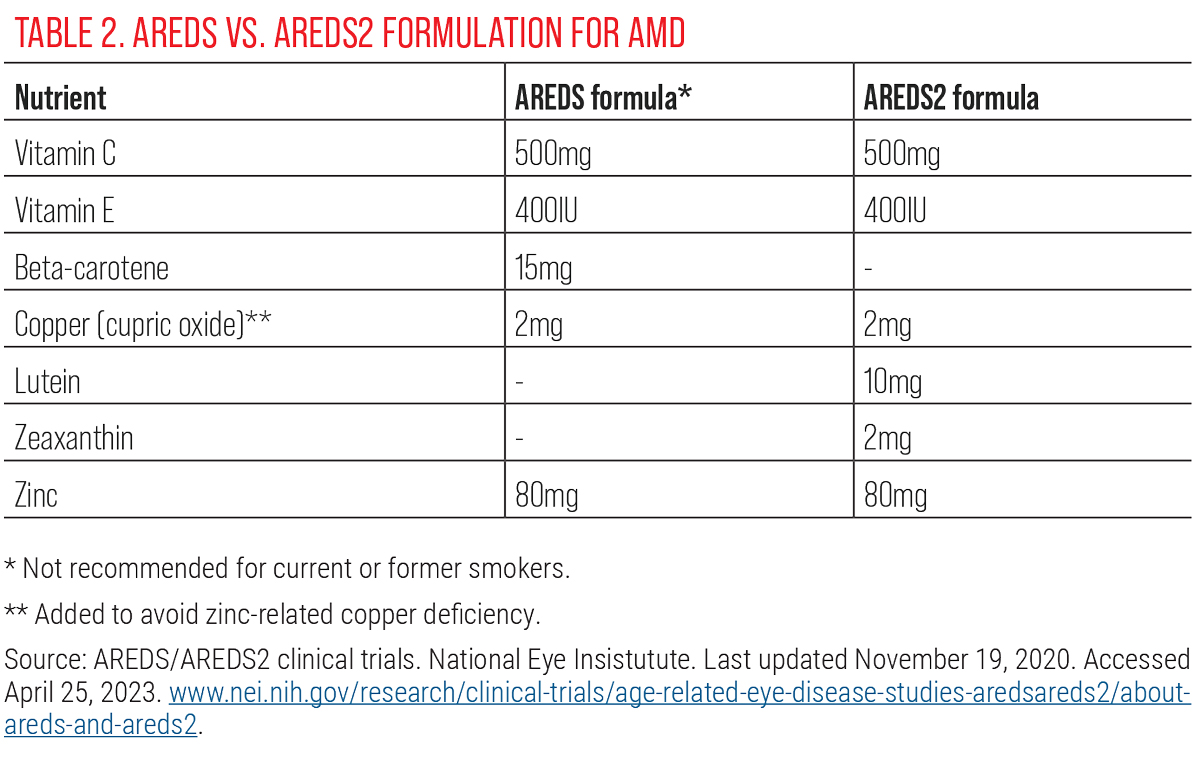

The AREDS study has also shown that 500mg/day of vitamin C supplementation reduced the risk of AMD progression. Due to the water-soluble nature of this vitamin, any excess intake is excreted in the urine, so there is low risk for overdose. This also suggests that vitamin C should be taken in equal doses throughout the day, rather than a single large dose per day. However, unless there is a deficiency, there are no clear benefits to high-dose vitamin C supplementation in routine patients at this time.15

Vitamin E. This fat-soluble vitamin is available in several isomers, but the one used in the AREDS formulation is alpha-tocopherol and has shown to decrease overall oxidative stress and inflammation by scavenging free radicals.9 The recommended daily dose in adults, both female and male, is 15mg.13 Avoid vitamin E in retinitis pigmentosa patients as it has been shown to increase the rate of progression.12 This should also be avoided in patients on blood thinners since it increases their risk for bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke.12

There are conflicting results regarding vitamin E and its relationship to AMD. The Beaver Dam Eye Study found that a vitamin E deficiency was linked with large drusen formation the Blue Mountains Eye Study showed increased risk for AMD progression with vitamin E supplementation, and the Eye Disease Case-Control Study found no significant difference.9 Given this, there is no compelling evidence to recommend high-dose vitamin E supplementation on its own to patients. However, due to its excellent anti-oxidative effects, many supplements include vitamin E in the formulation, including the AREDS formula with 400IU.

|

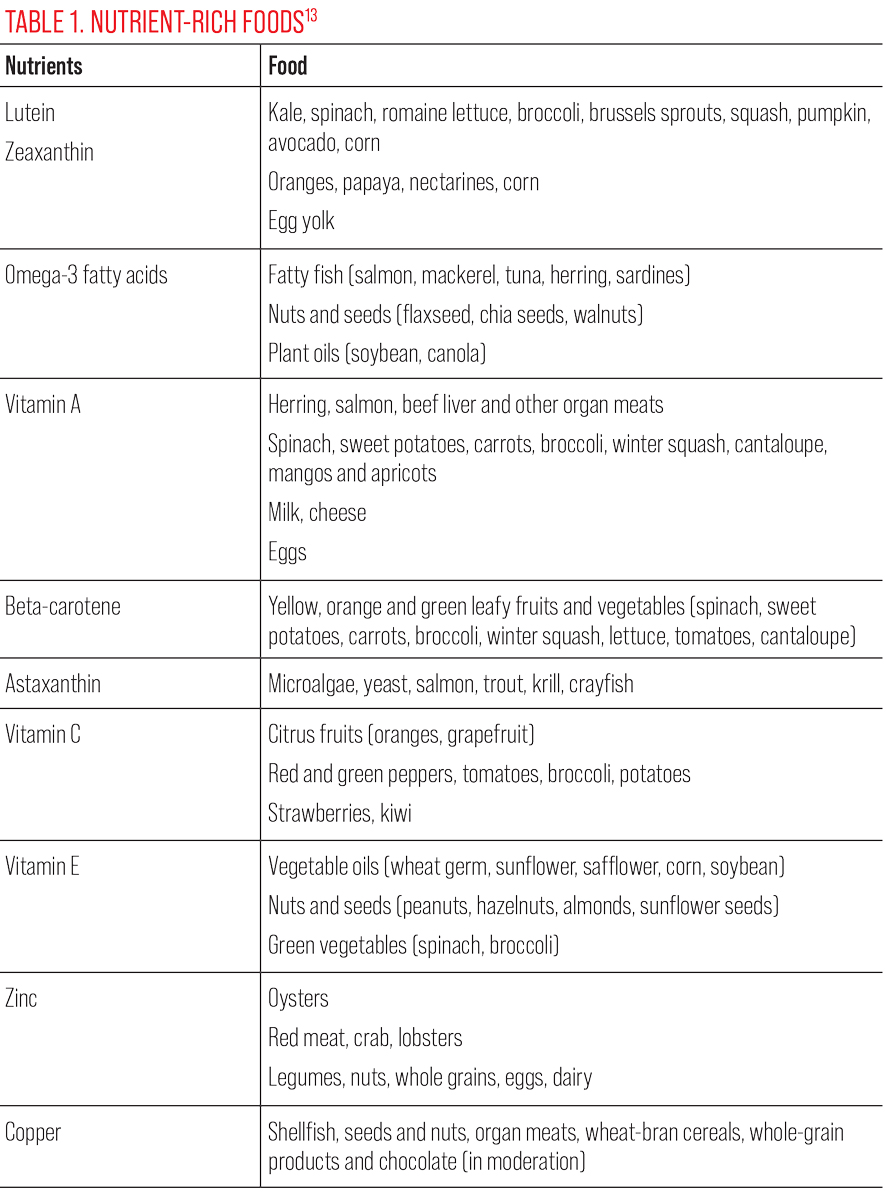

| Click table to enlarge. |

Carotenoids

Eyecare professionals should educate patients on these macula-enriching molecules.

Lutein and zeaxanthin. These pigmented xanthophylls are heavily concentrated in the macula and protect the area from oxidative stress caused by blue and UV light exposure.8 The recommended daily dose in adults is 10mg for lutein and 2mg for zeaxanthin.13 Lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation has shown to increase macular pigment optical density, improve visual acuity and increase contrast sensitivity on multifocal electroretinograms in both normal and diseased retinas.8,9

The Blue Mountains Eye Study also found that patients with high serum lutein and zeaxanthin had a significantly lower risk of AMD.9 In animal models, zeaxanthin has been shown to inhibit DR.8 Xanthophyll supplementation in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes has been shown to improve overall visual function and decrease symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, regardless of the level of retinopathy.16 The benefits of lutein and zeaxanthin impact both diseased and healthy retinas with limited adverse reactions, so these may be one of the few supplements that can be recommended to all patients interested in ocular health maintenance and should be emphasized in patients at higher risk for retinal disease.

|

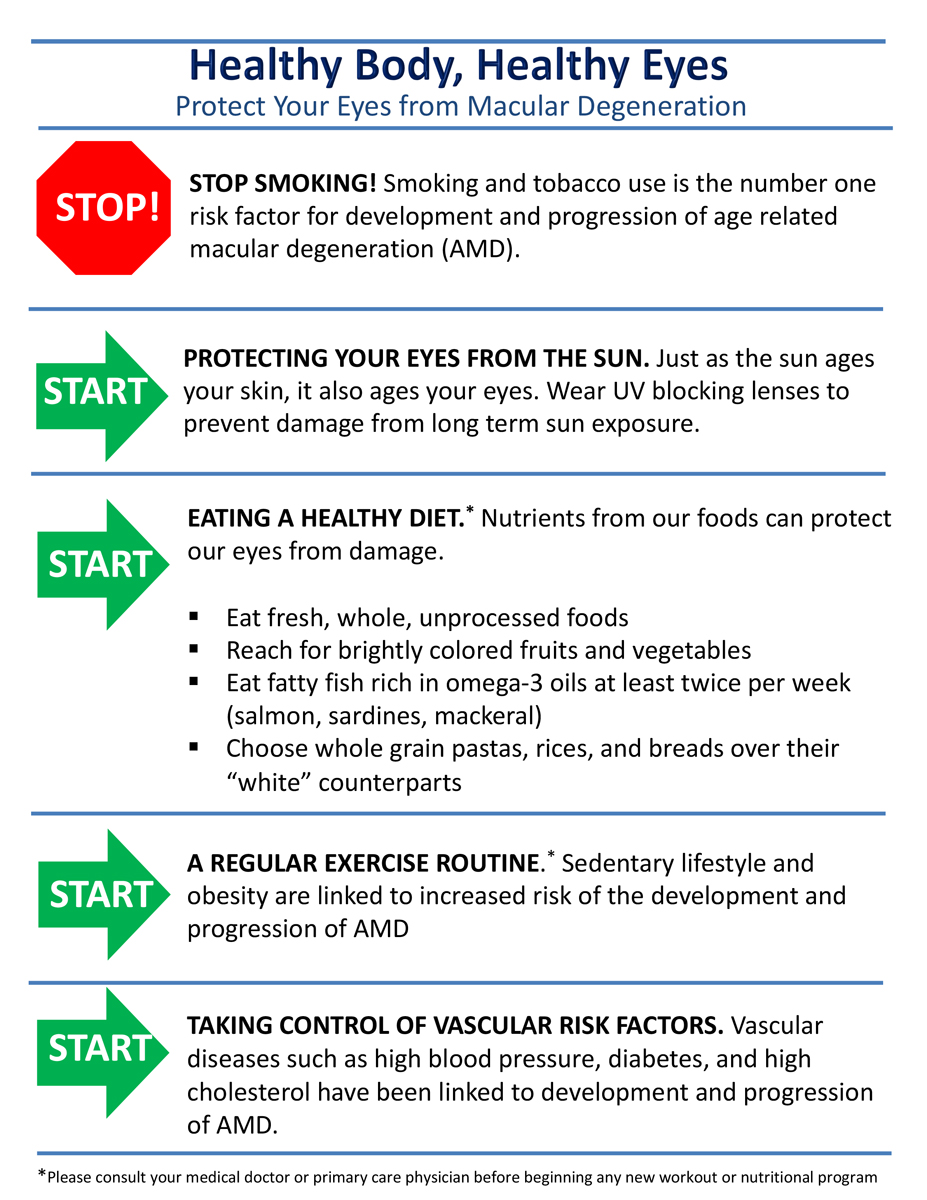

| Give your patients a reference sheet of AMD lifestyle modifications such as this one. Photo: Jessica Haynes, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Beta-carotene. This is yet another potent antioxidant present in small amounts in the RPE and is a precursor to vitamin A. Since beta-carotene increases the risk for lung cancer in smokers, it was removed from the original AREDS formulation and replaced with lutein and zeaxanthin in AREDS2, which proved to be slightly more efficacious.9 Although beta-carotene is a precursor of vitamin A, it does not carry the same risks as preformed vitamin A does in high doses.12

The recommended daily dose for adults is 15mg.13 Separate beta-carotene supplementation seems to have little benefit at this time, given the prevalence, efficacy and improved safety profile of the other carotenoids. In addition, excess beta-carotene (often found in supplement pills) has shown to be associated with an increased risk of AMD.17

Astaxanthin. One of the more powerful carotenoids is astaxanthin. This carotenoid has a chemical structure that fully spans cellular membranes with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. By scavenging measures, it is a far stronger antioxidant than zeaxanthin, canthaxanthin, lutein, B-carotene and alpha-tocopherol.

Astaxanthin neutralizes single oxygen molecules and scavenges radicals to prevent chain reactions, thus preserving membrane structure. This carotenoid also crosses both the blood-retinal and blood-brain barriers and may be beneficial in cardiovascular, immune, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases.18 While there is no recommended daily allowance for astaxanthin, studies have shown positive effects with between 6mg to 12mg daily.19

Fatty Acids

Proper supplementation of these in inflammatory diseases such as dry eye can offer patients relief and other advantages.

Omega-3s (docosahexanoic acid; DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid; EPA). These fatty acids form the phospholipid bilayer and outer segments of photoreceptors, making them crucial in retinal structure and function.8,9 DHA and EPA are long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, with the most abundant in the retina being DHA.8

DHA levels were significantly lower in donor eyes with AMD in comparison to normal eyes.8 Although studies have shown a reduced risk in choroidal neovascular membrane formation in red blood cells with high DHA concentrations, no improvement was noted in contrast sensitivity with DHA supplementation.8 This suggests that omega-3 supplementation cannot improve retinal function, but may protect it from further decline. One study found that consuming at least 500mg per day of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids reduced the risk of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy by 48%.20

The recommended daily dose is 1.6g for adult males and 1.1g for adult females.13 Omega-3 supplementation has also been shown to help with vitamin A absorption in retinitis pigmentosa patients.12 Take caution when using omega-3 supplementation in patients with clotting disorders or on blood thinners since high doses are known to increase prothrombin time.8

|

Source: AREDS/AREDS2 clinical trials. National Eye Insistutute. Last updated November 19, 2020. Accessed April 25, 2023. www.nei.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/age-related-eye-disease-studies-aredsareds2/about-areds-and-areds2. Click table to enlarge. |

Minerals

The trace mineral zinc is necessary in over 300 enzymatic reactions, making it an important part of phototransduction.9 Low levels of zinc have been associated with decreased night vision and RPE degradation.8 The recommended daily dose is 11mg for adult males and 8mg for adult females.13 Zinc can limit the absorption of fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines, while diuretics can limit the absorption of zinc.13 It has been shown to reduce the risk of AMD progression with the exception of certain genetic variations of complement factor H, so it may be worth considering genetic testing to guide supplementation decisions in these patients.9

Zinc reduces the amount of copper your body absorbs, and high doses of zinc (like in AREDS) can cause a copper deficiency. For that reason, it is recommended to take 2mg of copper along with a zinc supplement.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet has garnered a lot of attention for its promotion of longevity and chronic disease prevention. Studies have shown that adhering to this diet reduces the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline.21,22 In fact, the Greek island of Ikaria and Italian island of Sardinia make up two of the five blue zones, meaning they contain one of the highest concentrations of centenarians.22 So, what exactly is this heart-healthy diet made of?

- Olive oil, vegetables (leafy greens), fruits, breads/cereals: one to two servings per every meal

- Nuts (walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, pistachios), dairy: one to two servings daily

- Legumes, fatty fish/seafood: two or more servings weekly

- Poultry, eggs: two servings weekly

- Red meat, sweets: <two servings/week

- Red wine: in moderation (one to two glasses/day for men; one glass/day for women)

|

| This fundus image shows clinically significant macular edema with best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20. Photo: Julie Torbit, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The Mediterranean diet is rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids, making it ideal for disease prevention and longevity. Additionally, the diet depends on fresh ingredients, which are abundant in that area. Geographic atrophy has been seen to progress slower in patients adhering to a Mediterranean diet, further supporting its anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective characteristics.23 In contrast, high glycemic diets (such as the Western diet) can lead to the accumulation of cytotoxic advanced glycation end products, which promote AMD and DR progression.24

Takeaways

Now that we have the information to share with our patients, how can we convince them to use this knowledge and implement potentially vision-saving lifestyle changes? Old habits tend to die hard, so it’s important to emphasize the value of starting small. For example, swapping white bread with whole grain bread or eliminating desserts can significantly lower the patient’s glycemic peaks without causing a shock to their dietary habits.25

Helping the patient find a convincing purpose to make these changes can also be a strong source of motivation. Visual impairment has been linked with depression, increased risk for falls, and early mortality.26 Identifying reasons for the patient to keep seeing, whether it’s their grandchildren, their hobbies or ability to function independently, may make a difference. The use of educational handouts outlining the relationship between adequate nutrition and eye health can also improve patient compliance.

It is important to consider whether there are any limitations in the patient’s systemic health for proper nutrient absorption (e.g., Crohn’s disease, pancreatic insufficiency, cirrhosis, celiac disease, frequent use of proton pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux, history of gall bladder removal) and to manage with their primary care provider accordingly.

Most vitamins and minerals are better absorbed by the body through food sources than supplements due to the inherent presence of enzymes and flavonoids.8 However, supplements must be taken with food to maximize absorption. Comanaging patients with a nutritionist can also promote overall well-being. Although we are fortunate enough to have the tools to treat many retinal conditions today, prevention is always the best cure in the long-run.

Dr. Komma serves as an externship coordinator and staff optometrist at the Kernersville VA Health Care Center. She graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry and completed her ocular disease residency at the Salisbury VA Medical Center. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. She has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-8. 2. Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106-16. 3. Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, et al. global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1580-91. 4. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917-28. 5. da Costa JP, Vitorino R, Silva GM. A synopsis on aging—theories, mechanisms and future prospects. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;29:90-112. 6. Country MW. Retinal metabolism: a comparative look at energetics in the retina. Brain Res. 2017;1672:50-7. 7. Ursini F, Maiorino M, Forman HJ. Redox homeostasis: the golden mean of healthy living. Redox Biol. 2016;8:205-15. 8. Walchuk C, Suh M. Nutrition and the aging retina: A comprehensive review of the relationship between nutrients and their role in age-related macular degeneration and retina disease prevention. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2020;93:293-332. 9. Rinninella E, Mele MC, Merendino N, et al. The role of diet, micronutrients and the gut microbiota in age-related macular degeneration: new perspectives from the gut⁻retina axis. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1677. 10. Sajovic J, Meglič A, Glavač D, et al. The role of vitamin A in retinal diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1014. 11. Saenz-de-Viteri M, Sádaba LM. Optical coherence tomography assessment before and after vitamin supplementation in a patient with vitamin A deficiency: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(6):e2680. 12. Berson EL, Rosner B, Sandberg MA, et al.A randomized trial of vitamin A and vitamin E supplementation for retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(6):761-72. 13. Vitamin and mineral supplement fact sheets. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-vitaminsminerals/. 14. Sant DW, Camarena V, Mustafi S, et al. Ascorbate suppresses VEGF expression in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(8):3608-18. 15. Lim JC, Caballero Arredondo M, Braakhuis AJ, Donaldson PJ. Vitamin C and the lens: new insights into delaying the onset of cataract. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3142. 16. Chous AP, Richer SP, Gerson JD, Kowluru RA. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study (DiVFuSS). Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(2):227-34. 17. Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, et al. Dietary antioxidants and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):334-41. 18. Wolf AM, Asoh S, Hiranuma H, et al. Astaxanthin protects mitochondrial redox state and functional integrity against oxidative stress. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21(5):381-9 19. Nagaki Y. Hayasaka S, Yamada T, et al. Effects of Astaxanthin on accommodation, critical flicker fusion and pattern visual evoked potential in visual display terminal workers. J Tradit Med. 2002:19(5):170-3. 20. Sala-Vila A, Díaz-López A, Valls-Pedret C, Cofán M, et al. Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) Investigators. Dietary marine ω-3 fatty acids and incident sight-threatening retinopathy in middle-aged and older individuals with type 2 diabetes: prospective investigation from the PREDIMED Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(10):1142-9. 21. Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean diet; a literature review. Nutrients. 2015;7(11):9139-53. 22. Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(9):1076-83. 23. Agrón E, Mares J, Chew EY, Keenan TDL; AREDS2 Research Group. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and geographic atrophy enlargement rate. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022;6(9):762-770. 24. Francisco SG, Smith KM, Aragonès G, et al. Dietary patterns, carbohydrates and age-related eye diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2862. 25. Rowan S, Jiang S, Korem T, et al. Involvement of a gut-retina axis in protection against dietary glycemia-induced age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(22):E4472-81. 26. Looking ahead: Improving our vision for the future. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/resources/infographics/future.html. Accessed April 25, 2023. |