A little girl in kindergarten, a female AARP member, and a college wrestler may seem like they have little in common, but these patients could have more similarities than you think.

Today, the typical eating disorder patient who walks into your practice may not be a teenage girl. While the incidence of eating disorders has doubled since the 1960s, according to the

We have been seeing eating disorders across the age spectrum(patients) as young as seven and well into their 60s, says Cynthia Bulik, Ph.D., Director of the Eating Disorders Program at the

Eating disorders are serious illnesses with a biological basis modified and influenced by emotional and cultural factors, according to the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA). Along with environmental factors, genetics play a key role in the onset of eating disorders, Dr. Bulik says. Genetic factors account for over 50% of liability to anorexia nervosa, and they are similarly high for bulimia, she says.

Genes provide the predisposition and environment may act as the release, Dr. Bulik says. Genes load the gun and environment pulls the trigger.

Nearly 10 million females and one million males suffer from eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia, and approximately 25 million more struggle with binge eating disorder, NEDA reports. As the incidence of eating disorders increases and a wider variety of age groups and more males are being reported with these often life-threatening conditions, chances are you are already treating a patient with an eating disorder.

Eating Disorder Definitions Anorexia nervosa. Individuals with anorexia nervosa are unable or unwilling to maintain a body weight that is normal or expected for their age and height. Typically, this means that a person is less than 85% of their expected weight. Even when underweight, individuals with anorexia continue to be fearful of weight gain. Their thoughts and feelings about their size and shape have profound impact on their sense of self and their self-esteem. They often do not recognize or admit the seriousness of their weight loss and they deny that it may have permanent adverse health consequences. Women with anorexia nervosa often stop having their periods.

There are two subtypes of anorexia nervosa. In the restricting subtype, people maintain their low body weight purely by restricting food intake and, possibly, by exercise. Individuals with the binge-eating/purging type also restrict their food intake, but also regularly engage in binge eating and/or purging behaviors such as self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics or enemas. Many people move back and forth between subtypes during the course of their illness.

Bulimia nervosa. Individuals with bulimia nervosa experience binge eating episodes in which they eat an unusually large amount of food, usually in a discrete period of time, and feel out of control while doing so. The sense of being out of control is what distinguishes binge eating from overeating. Binge eating is followed by attempts to undo the consequences of the binge by using unhealthy compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, enemas, diuretics, severe caloric restriction, or excessive exercising.

There are also two subtypes of bulimia nervosa. The purging type includes those individuals who self-induce vomiting or use laxatives, diuretics, or enemas. The non-purging type refers to those who compensate through excessive exercising or dietary fasting.

Binge eating disorder. This term was officially introduced in 1992 to describe individuals who binge eat but do not regularly use inappropriate compensatory weight control behaviors such as fasting or purging to lose weight. Binge eating may involve rapid consumption of food, uncomfortable fullness after eating, and eating large amounts of food when not hungry. Feelings of shame and embarrassment are prominent. Binge eating disorder is often, but not always, associated with overweight and obesity. Previous terms used to describe these problems included compulsive overeating, emotional eating, or food addiction.

Source: Cynthia Bulik, Ph.D., Director of the Eating Disorders Program at the

Changing Patient

A decade ago, treatment programs were enrolled primarily with adolescent girls, Dr. Bulik says. Now, she is also seeing more middle-aged women and prepubescent girls.

Eating disorders are not simply disorders of choice, Dr. Bulik says. They are not motivated by vanity, or the desires of young girls to look like models. Those are old myths that fail to capture the current science and understanding about eating disorders.

A recent study conducted by researchers at the British Pediatric Surveillance Unit found that eating disorders may appear even among 5-year-olds. The British team of researchers suggested that anorexia and bulimia may seriously affect childrens health, and that hundreds of children are hospitalized annually because of eating disorders.

This prevalence of younger girls developing some type of eating disorder is further supported by research from NEDA, which reports that four out of five 10-year-old children are afraid of being fat; nearly half of the children between first and third grades say they want to be thinner, and two out of 10 girls have some type of disordered eating.

On the other end of the age spectrum, elderly women are also developing eating disorders. Australian researchers at the

Dr. Bulik points to three patterns of older women with eating disorders:

Women who had eating disorders in youth who have gotten better, lived their livesoften married with childrenand develop anorexia again in mid-life.

Women who have had dormant symptoms for years but never develop the full-blown disorder until mid-life.

New-onset cases, in which environmental triggers play a role, that generally come later in life.

So, someone who is genetically vulnerable may only express the disorder later in life, when she starts exercising obsessively after a divorce and (embraces) a perception that the only way she will make it back on the dating scene is by losing 20 pounds, Dr. Bulik says.

The majority of patients with eating disordersspecifically anorexiastill develop them in the years around puberty, according to Doug Bunnell, Ph.D., clinical director of the Renfrew Center of Connecticut and board member of the National Eating Disorders Association. Those who develop bulimia nervosa usually do so later, generally around ages 13 to 17. Many patients with anorexia go on to develop bulimia within two years, Dr. Bunnell says. It appears to be common for adults to have had a history of childhood eating disorders that may go into remission but reappear in times of acute stress or trauma.

Eating disorders affect all races and classes, although there are some racial/ethnic differences. African American women have lower rates of anorexia and bulimia, but comparable rates of binge eating disorder, Dr. Bunnell says.

Athletes in certain sports are particularly at high risk for eating disorders. Female gymnasts, ice skaters, dancers and swimmers all have higher rates of eating disorders. In a study of Division I athletes, more than one-third of female athletes reported attitudes and symptoms that placed them at risk for anorexia. Male athletes are also at risk, especially those in sports such as wrestling, bodybuilding, crew, running, cycling and football.

Symptoms to Watch

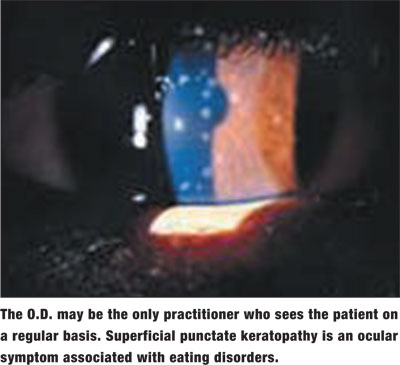

Optometrists may be the only practitioners who see these patients on a regular basis, says Ellen Rome, M.D., chair of the media committee for the

Other systemic symptoms include dizziness, low heart rate, and complaints of frequent headaches, Dr. Rome says. Inflamed cheeks can be a sign of vomiting, and callused hands and knuckles can also be potential symptoms.

Patients with eating disorders may present with the following ocular symptoms:

Punctate keratopathy.1

Primary vasospatic syndrome, which may alter the conjunctival vessels and cause corneal edema, retinal, arterial and venous occlusions, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and glaucoma.2

Severe dry eye and corneal ulceration.3

While many of these symptoms may be non-specific, a practitioner should hear, listen, look and recognize potential indicators that could mean that their patient has an eating disorder, Dr. Rome says.

Course of Treatment

If you notice one of your patients has suddenly lost weight, it should prompt the question, How have you done that? Dr. Rome advises. You should also be an observer of moods. A distress indicator to look for is if a child used to be engaged and is now removed and quiet. Also, patients with anorexia may be less likely to look you in the eye.4

If the patient is a child, optometrists should comment privately to a parent following the exam, Dr. Rome says. Tell the parent, This is what I see, and I am worried about this. It is good to reach out. Never underestimate the role of a caring adult.

Children and adolescents are often resistant to treatment due to the intense anxiety about weight gain, Dr. Bulik says. Raise the issue of potential eating disorders with concern and respect, she adds. Raise your concerns with your patient or his or her parents in an open, caring and supportive manner. Do not blame, and be mindful of shame and denial, she says. Communicate your concerns. Share your concrete observations and why they make you think the patient should have an evaluation. Explain that you think these things may indicate that there could be a problem that needs professional attention.

Once the issue has been addressed, ask your patient or his or her parent to explore these concerns with a counselor, doctor, nutritionist or other health professional who is knowledgeable about eating issues. It is also helpful to have written material available, Dr. Bulik says. If your patient or family is unable to hear your concern at the time, have Web sites and written material available for treatment centers in your area.

Dr. Bunnell adds: It is important to address the concern, but to do it in a way that promotes discussion and minimizes the chance of denial. Expressions linked to health risks, depression, anxiety and the limitations of excessive thinness or binge/purge behaviors are better to focus on than direct expression regarding weight or shape. It is often the case that people with eating disorders will resist care and treatment, so it may be necessary to follow up an initial inquiry with consistent and persistent concern, he says.

Eating disorders are serious and also significant mental health problems. In fact, eating disorders have the highest premature mortality rate of any psychiatric diagnosis, Dr. Bunnell says. As the incidence of eating disorders continues to rise and the demographics of patients with eating disorders expand, optometrists should be aware of potential symptoms and the appropriate course of action in treating and referring these patients.

Treatment is complicated. Recovery is possible, but is hindered by stigma and insurance policies that deny adequate care for most patients and their families, Dr. Bunnell says. Optometrists can help by spreading the word about the significance and power of these disorders. We need to combat the perception that they are benign, vanity-based illnesses, when in fact they have significant genetic components and are, today, conceptualized as serious brain disorders.

1. Gilbert JM, Weiss JS, Sattler AL, Koch JM. Ocular manifestations and impression cytology of anorexia nervosa. Ophthalmology 1990 Aug;97(8):1001-7.

2. Flammer J, Pache M, Resink T. Vaspospasm, its role in the pathogenesis of diseases with particular reference to the eye. Prog Retin Eye Res 2001 May;20(3):319-49.

3. Velasco Cruz AA, Attie-Castro FA, Fernandes SL, et al. Adult blindness secondary to vitamin A deficiency associated with an eating disorder. Nutrition 2005 May;21(5):630-3.

4. Cipolli C, Sancini M, Tuozzi G, et al. Gaze and eye-contact with anorexic adolescents. Br J Med Psychol 1989 Dec;62 (Pt 4):365-9.