|

Dr. Gurwood thanks Denise Diaz Aguayo, OD, for contributing this case.

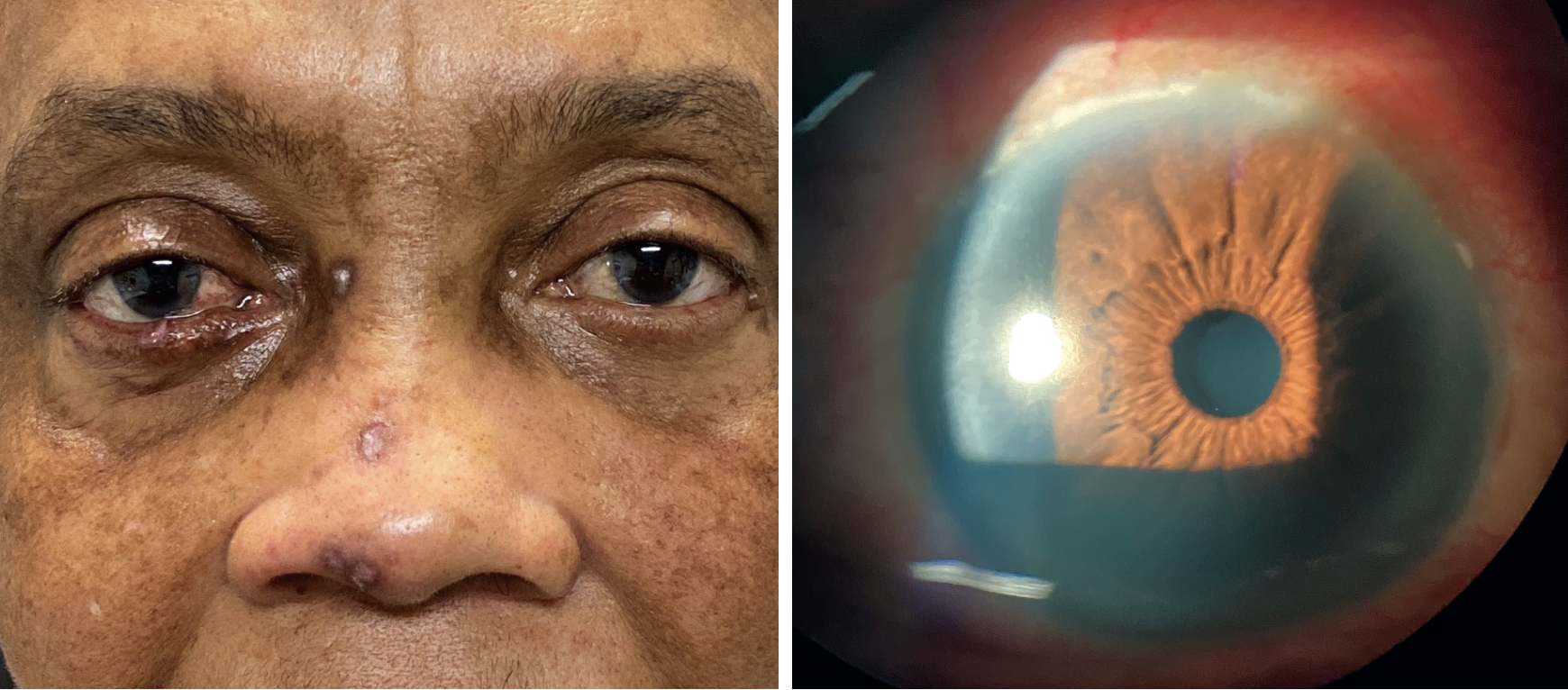

A 58-year-old woman presented to the ophthalmology department on referral from the emergency department with a red right eye of seven days’ duration. She denied trauma or use of contact lenses. She was COVID negative. Her systemic history was positive for well-controlled hypertension. She was not diabetic.

She denied trauma or the use of contact lenses. She denied allergies of any kind.

Clinical Findings

Her best uncorrected entering visual acuities were 20/30 OD, OS, OU at distance and near. A refraction of +0.50/+2.50 improved acuity to 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS at distance and near. Her external examination was normal and there was no afferent defect.

The important biomicroscopic findings OD are demonstrated in the photographs. Her intraocular pressures measured 12mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS, using Goldmann applanation tonometry. The dilated examination found cup/disc ratios of 0.2 round, with distinct margins and normal grounds.

|

|

Is there anything in the patient’s ocular or non-ocular presentation that suggests the nature of her condition? Click image to enlarge. |

Additional Testing

The patient’s corneal sensitivity was measured and found to be normal in both eyes. Sodium fluorescein staining demonstrated mild punctate epitheliopathy, greater in the right eye than the left, with no frank pooling. Anterior segment photography was completed.

The eyelids were everted to rule out the presence of large papillae or follicles. In addition, the preauricular, submandibular and sublingual lymph nodes were palpated.

What would be your diagnosis in this case? What is the patient’s likely prognosis?

Diagnosis

This month’s patient is experiencing peripheral ulcerative keratitis OD preceding herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO).

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK), sometimes referred to as marginal keratitis, is defined as one or more zones of peripheral corneal inflammatory response.1-10 The condition is also known synonymously as sterile keratitis, infiltrative keratitis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis and, when a contact lens-related etiology is suspected, contact lens–associated red eye (CLARE), contact lens–induced peripheral ulcer (CLPU) and contact lens–related infiltrate.1-14 It can be produced following chronic exposure to an adjacent antigen (e.g., make-up, chemical exposure, microbes), a chronic mechanical stimulus (e.g., debris, eyelid or eyelash), induced hypoxia (from contact lens wear) or as a sequela of an inflammatory or vasculitic systemic disease such as herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Beçhet’s disease, engraftment syndrome (an early complication of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation), Wegener’s granulomatosis (polyangiitis) and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1-21

Disease Course

Patients with PUK may range in presentation from completely asymptomatic to severely symptomatic, depending upon the extent and duration of the reaction. Symptoms are graded as mild, moderate and severe and may include ocular discomfort (e.g., burning, foreign body sensation, grittiness), photophobia and chronic tearing.6,18 Vision may be variably affected depending upon the level of anterior chamber reaction and overall central corneal health.1-7

Bulbar conjunctival injection may be absent to mild early in the presentation. However, if the underlying cause is not addressed, the condition and its signs and symptoms will worsen; if left unmanaged, it can proceed to vision-threatening status (e.g., thinning with perforation).1-20

The palpebral conjunctiva may demonstrate subtle conjunctival chemosis.11-14 The key diagnostic sign is one or more focal areas of grayish subepithelial infiltrate near the limbus, usually located in the inferior cornea.1,2,11-18 The positions where the cornea interacts with the lower eyelid margin are particularly common sites of involvement.1,2,13-18

When the overlying epithelium is compromised, the defect is usually seen as an interrupted stippling much smaller than the area of infiltrate.16-18 This is in contradistinction to infectious corneal ulcer, which demonstrates a large, singular continuous area of epithelial defect virtually equal to the area of stromal infiltrate.16 Characteristically, there are zones of unaffected limbal cornea.4,9,10,18 In rare instances, PUK may be accompanied by other inflammatory ocular sequelae, such as mild anterior uveitis or folds in Descemet’s membrane associated with corneal edema.

Blepharitis and diseases that can alter eyelid homeostasis like herpes zoster ophthalmicus are positioned to be major contributors secondary to their effects on the lid margin.2,4,10-12,13,17-19 Patients with concomitant ocular surface disease such as chronic dry eye, entropion or allergic conjunctivitis are at extended risk.

HZO is a manifestation of the varicella zoster virus (VZV).19,20 The virus typically enters the human system through the conjunctiva and/or nasal or oral mucosa and takes residence in the sensory ganglia throughout the body.19,20 The herpes zoster rash (shingles) commonly presents in the facial and mid-thoracic-to-upper lumbar dermatomes.4,10,19,20 An active immune system suppresses the virus and it will lie dormant until the body’s immunity becomes relaxed from natural aging or other triggers such as chemotherapy or other systemic disease or pressure.

When activated, the virus begins to replicate along the route of the ganglia. Due to widespread community exposure to the virus, nearly 100% of the population develops antibodies to the disease by age 60.4,19,20 Cell-mediated immunity keeps the virus suppressed and periodic natural re-exposures helps to prevent the virus from activating as herpes zoster ophthalmicus or oticus.

HZO results when the trigeminal ganglion is invaded by the VZV. Neuronal spread of the virus occurs along the ophthalmic (1st) and less frequently the maxillary (2nd) division of cranial nerve five.4,10,18-20 Vesicular eruptions occur at the terminal points of sensory innervation, causing extreme pain. Nasociliary nerve involvement will most likely entail ocular inflammation, typically affecting the tissues of the anterior segment.4,10,18-20 Contiguous spread of the virus may lead to involvement of other cranial nerves resulting in optic neuropathy (CN II) or isolated cranial nerve palsies (CN III, IV, or VI).18-21 Numerous manifestations in HZO are possible due to the varied pathophysiologic processes initiated by the VZV. 4,10,18-21 Vascular and neural inflammation, immune and general inflammatory reactions are plausible.

Presentation and Management

Classic PUK presents as a localized immune response driven by antigen-antibody complexes that deposit in the peripheral corneal stroma.11,20-23 Generically, the mechanism is an inflammatory process that initiates a cascade resulting in the influx of leukocytes and plasma molecules to the site of the tissue damage.1,24,25

The inciting etiology will dictate the specific cellular response.15,16,25-27 Initially, the overlying epithelium remains predominantly intact; however, as inflammatory cells accumulate to neutralize the offending reaction, collagenolytic enzymes (collagenases) released from these cells induce noninfectious ulceration (open, non-healing wound with infiltrate).4,10,18-20,28 Matrix metaloprotinase-9 appears to be a prominent player in the initiation of the epithelial basement membrane degradation that precedes corneal ulceration.28

Historically, bacterial exotoxins from staphylococcal organisms are considered the primary etiology.11,13,15,22 However, clearly not all cases are caused by microbial flora.4,9,10,18-20 When eyelid disease is not an overt contributor, consider systemic autoimmune disorders, mechanical events and hypersensitivity reactions to foreign substances such as topical drugs, including phenylephrine, gentamicin, atropine, pilocarpine and dorzolamide.2,3-11,15,16,18,26,27 Corneal hypoxia (ipsilateral vascular insufficiency produced by poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes, substance abuse) and bacterial biofilm associated with soft contact lens wear represent additional etiologies.4,10,18-20

The treatment strategy for PUK must address both extinguishing the inflammatory response and removing or controlling the causative etiology.1-27 In cases where microbial flora is implicated, aggressive control of eyelid and ocular surface bacteria can be accomplished via topical and oral antibiotics. Generic staphylococcal blepharitis can be treated with traditional topical fluoroquinolone antibiotic drops and or ointments QID. Mechanical cleaning of the eyelids to soften and remove debris/microbes should be employed along with warm compresses. Commercially available lid cleansers such as Ocusoft or generic “no more tears” baby shampoos two to four times daily work well.29 Topical application of tea tree oil and metronidazole ointment BID, along with oral ivermectin dosed once and repeated in seven days if necessary, is indicated in cases of suspected Demodex infestation.30

In cases of rosacea (meibomian gland dysfunction), oral tetracycline 500mg BID PO, doxycycline 100mg BID PO or azithromycin (Z-pak) can be prescribed.31

Since inflammation is an integral portion of the entity’s histopathology, its mitigation can be accomplished with either topical antibiotic-steroid combination drops or ointments BID to QID or the addition of a topical steroid to the topical antibiotic.2-27 Topical corticosteroid drops and ointments include fluorometholone, prednisolone acetate, loteprednol etabonate and difluprednate, dosed BID to Q3h depending on the severity of the case.2-27

In the event the reaction is severe or the diagnosis delayed, a 60mg to 80mg oral prednisone taper over 10 days may be also be required. This may be prescribed by the eye doctor or requested of the medical team through conference or correspondence. It is not unreasonable to take a stepped approach if the condition is identified early in presentation, evaluating whether each topical intervention is succeeding before moving on. Since topical and oral steroids may increase intraocular pressure IOP, management must include monitoring. In cases with significant anterior segment inflammation (iritis), cycloplegia may be warranted. This can be achieved with cyclopentolate 1% to 2%, homatropine 5% or atropine 1%, QD/BID as severity dictates.

PUK associated with drug hypersensitivity necessitates discontinuing the noxious agent and controlling the ocular inflammation as mentioned above.26,27 Cases involving contact lenses require discontinuing lens wear, protecting the cornea with a topical antibiotic or antibiotic-steroid combination drop and ointment, rehabilitating the ocular surface and considering refit or redesign of the contact lenses.

HZO is best treated by initiating oral antiviral therapy as soon as the condition is diagnosed. Oral acyclovir 600mg to 800mg 5x/day for seven to ten days is standard. Alternately, famciclovir (500mg PO TID) and valacyclovir (500mg BID/TID) for a 10-day course are acceptable.19,20,32 Timing is crucial. If these agents are started within 72 hours of the onset of the acute rash, they will significantly shorten the period of pain, viral shedding, rash and anterior segment complications.32

Valacyclovir and famciclovir may better reduce the incidence and severity of post-herpetic neuralgia compared with acyclovir. However, oral antiviral agents cannot totally prevent post-herpetic neuralgia.32 Oral corticosteroids may be used as adjuvant therapy to alleviate HZO-related pain and associated facial edema; 40mg to 60mg of prednisone daily, tapered slowly over 10 days is recommended. Topical care of the skin lesions may be aided by applying an antibiotic or antibiotic-steroid ointment to the affected areas twice daily along with dermatologic antihistamine and drying agents such as calamine lotion, Calahist lotion or Domeboro soaks.

Proper ocular management is dependent upon the severity of inflammation and the tissues affected.4,10,18,-21 When uveitis with or without PUK is present, cycloplegia is warranted and topical steroids can be used judiciously. Prophylaxis with a broad-spectrum antibiotic can be achieved using a combination ointment Qhs to BID if there is any compromised cornea. Finally, palliative treatment may consist simply of cool compresses; however, some patients may require oral analgesics in severely painful cases. Tricyclic antidepressants, antiseizure drugs, opioids, and topical analgesics are pain relief options in severe cases.32 Cimetidine (H2-histamine receptor blocker) 400mg PO BID may afford some additional relief from the neuralgia, though the mechanism by which this occurs is not entirely understood.33

The Shingles Prevention Study Group demonstrated that a VZV vaccine boosted cell-mediated immunity and significantly reduced HZO-related morbidity and post-herpetic neuralgia in older adults without causing or inducing an actual herpes zoster outbreak.34 Overall, VZV vaccine reduced the incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia by 66.5% and the incidence of zoster outbreak by 51.3%.34 It is safe to recommend vaccination following an HZO event after six months has passed.

The worst cases, where inflammation is severe, will likely require oral or intravenous supplementation to attack the underlying disease process; options include systemic corticosteroids and immunomodulating agents.6-10

Prognosis

The patient in this case was placed on a topical cycloplegic (atropine 1% BID), a topical fluoroquinolone antibiotic QID, a topical steroid QID and a steroid antibiotic ointment HS. The patient was asked to use cool compresses and over-the-counter analgesics as permitted by her medical team for any residual pain (she had no allergies or contraindications). She was also asked to keep her eyelids clean using a baby shampoo regimen BID OU. She was asked to return in follow up in four to seven days to rule out the need for the addition of an oral steroid taper and to see if any additional signs pointed to undiagnosed systemic disease requiring laboratory testing.

When she returned, the ocular condition had resolved nicely with all areas of peripheral infiltrates regressing. The uveitis had also regressed significantly. She no longer had conjunctival injection and she was now free of pain and photophobia.

Upon inspection of her face, there were now three distinct excoriative lesions on the first dermatome of the right side of face (ipsilateral to the red eye), one on the eyebrow, one at the top of the bridge of the nose and one at the tip of the nose (Hutchinson’s sign). The PUK had foreshadowed HZO.

The medical team was consulted and the patient was promptly started on oral antiviral medicine, 500mg three times a day by mouth, to both combat herpes zoster ophthalmicus and to minimize the risk of post-herpetic neuralgia. The patient was asked to use calamine lotion, Calahist lotion or Domeboro soaks to keep the excoriative lesions dry and then apply some Polysporin ointment to each region to prevent secondary infection.

The patient returned in one week with almost full resolution of the peripheral ulcerative keratitis and 60% resolution of this herpes zoster ophthalmicus skin rash with minimal post-herpetic neuralgia. The final follow-up was set for two to four weeks hence, barring complications.

Dr. Gurwood is a professor of clinical sciences at The Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. He is a co-chief of Primary Care Suite 3. He is attending medical staff in the department of ophthalmology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Zheng Y, Kaye AE, Boker A, et al. Marginal corneal vascular arcades. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(12):7470-7. 2. Gupta N, Dhawan A, Beri S, D'souza P. Clinical spectrum of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. J AAPOS. 2010;14(6):527-9. 3. Pereira MG, Rodrigues MA, Rodrigues SA. Eyelid entropion. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(3):52-8. 4. Gupta N, Sachdev R, Sinha R, Titiyal JS, Tandon R. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus: disease spectrum in young adults. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;18(2):178‐182. 5. Sweeney DF, Jalbert I, Covey M, et al. Clinical characterization of corneal infiltrative events observed with soft contact lens wear. Cornea. 2003; 22(5):435-42. 6. Li Yim JF, Agarwal PK, Fern A. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis presenting as bilateral marginal keratitis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35(3):288-90. 7. Dai E, Couriel D, Kim SK. Bilateral marginal keratitis associated with engraftment syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cornea. 2007;26(6):756-8. 8. Aust R, Kruse FE, Volcker HE. Therapy refractory marginal keratoconjunctivitis in a child. Wegener's granulomatosis in a child with initial manifestation in the eye. Ophthalmologe. 1997; 94(3):240-1. 9. Glavici M, Glavici G. Marginal keratitis in Behcet's disease. Oftalmologia. 1997; 41(3):224-7. 10. Neves RA, Rodriguez A, Power WJ, et al. Herpes zoster peripheral ulcerative keratitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cornea. 1996;15(5):446‐450. 11. Jayamanne DG, Dayan M, Jenkins D, Porter R. The role of staphylococcal superantigens in the pathogenesis of marginal keratitis. Eye. 1997; 11(Pt 5):618-21. 12. Viswalingam M, Rauz S, Morlet N, Dart JK. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children: diagnosis and treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(4):400-3. 13. Robin JB, Dugel R, Robin SB. Immunologic disorders of the cornea and conjunctiva. In: Kaufman HE, Barron BA, McDonal MB, eds. The Cornea, 2nd edition. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998; 551-95. 14. Sharma N, Venugopal R, Singhal D, Maharana PK, Sangwan S, Satpathy G. Microbial Keratitis in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: A Prospective Study. Cornea. 2019;38(8):938‐942. 15. Bouchard CS. Noninfectious keratitis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. Mosby-Elsevier, St. Louis, MO 2009:454-65. 16. McLeod SD. Infectious keratitis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. Mosby-Elsevier, St. Louis, MO 2009:466-91. 17. Sobolewska B1, Zierhut M. Ocular rosacea. Hautarzt. 2013 Jul;64(7):506-8. 18. Mondino BJ, Brown SI, Mondzelewski JP. Peripheral corneal ulcers with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86(5):611‐614.Bernardes TF, Bonfioli AA. Blepharitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(3):79-83. 19. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2 Suppl):S3-12.. 20. Nithyanandam S, Dabir S, Stephen J, et al. Eruption severity and characteristics in herpes zoster ophthalmicus: correlation with visual outcome, ocular complications, and postherpetic neuralgia. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48(5):484-7. 21. Shin MK, Choi CP, Lee MH. A case of herpes zoster with abducens palsy. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(5):905-7. 22. Stern GA, Knapp A. Iatrogenic peripheral corneal disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1986; 26(4):77-89. 23. Pararajasegaram G. Mechanisms of uveitis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. Mosby-Elsevier, St. Louis, MO 2009:1105-12. 24. Hazlett LD, Hendricks RL. Reviews for immune privilege in the year 2010: immune privilege and infection. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18(4):237-43. 25. Radian AB. Erosive marginal keratitis due to pilocarpine allergy. Oftalmologia. 1999; 47(2):83-4. 26. Taguri AH, Khan MA, Sanders R. Marginal keratitis: an uncommon form of topical dorzolamide allergy. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 130(1):120-2. 27. Fini ME, Girard MT, Matsubara M. Collagenolytic/gelatinolytic enzymes in corneal wound healing. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1992;70(202):26-33. 28. Liu J, Sheha H, Tseng SC. Pathogenic role of Demodex mites in blepharitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(5):505-10. 29. Czepita D, Kuźna-Grygiel W, Czepita M, Grobelny A. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis as a cause of chronic marginal blepharitis. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2007;53(1):63-7. 30. Layton A, Thiboutot D. Emerging therapies in rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 Suppl 1):S57-65. 31. Akhyani M, Ehsani AH, Ghiasi M, Jafari AK. Comparison of efficacy of azithromycin vs. doxycycline in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized open clinical trial.Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(3):284-8. 32. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster antivirals and pain management. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2 Suppl):S13-20. 33. Miller A, Harel D, Laor A, et al. Cimetidine as an immunomodulator in the treatment of herpes zoster. J Neuroimmunol. 1989;22(1):69-76. 34. Holcomb K, Weinberg JM. A novel vaccine (Zostavax) to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(9):863-6. |