|

Botulinum toxin is best known as a cosmetic agent used to treat facial wrinkles, yet its origins and current application for our purposes is more importantly that of a therapeutic agent.1 Its use in the treatment of neuro-ophthalmic disorders, especially those in which traditional therapies are of limited benefit, has had a decades-long positive track record.2 Botulinum toxin has emerged as a safe and effective treatment for a number of previously refractive conditions associated with excessive muscle activity.3

It has been used to treat numerous types of strabismus in children and adults as both an adjunctive and alternative surgical therapy, as well as for various dystonias of the facial muscles.4 Dystonia is a syndrome dominated by involuntary sustained (tonic) or spasmodic (rapid or clonic) repetitive muscle contraction patterns, frequently causing twisting, flexing or extending and squeezing movements or abnormal postures.5-9 The most common facial dystonias are benign essential blepharospasm, Meige syndrome and hemifacial spasm.

|

|

Fig. 1. BEB, a common bilateral facial dystonia, involves the orbicularis oculi, procerus and corrugator musculature. Click image to enlarge. |

Background

Botulinum toxin is the most potent biologic neurotoxin known to man. It can cause botulism, a potentially fatal condition that causes neuromuscular paralysis. All botulinum toxins are produced by the anaerobic gram-negative bacterium, Clostridium botulinum.9 These neurotoxins are grouped into eight serotypes based on their immunologic properties. Of these eight, only three (A, B and E) cause flaccid paralysis in humans.9,10

Following intramuscular injection, botulinum toxin inhibits the release of acetylcholine from the motor nerve terminals, resulting in a temporary reduction in muscle contractions. Once injected, the toxin rapidly and firmly binds at receptor sites on the acetylcholine-related nerve terminals. Neuromuscular transmission ceases, and the target muscle atrophies. This chemical denervation effect is seen within five days with peak effect at two to three weeks and duration of action of three months.2 Since the nerve terminals recover their normal functions, the effects of botulinum toxin are not permanent.11 This reactivation of muscle activity may be considered both an advantage and a disadvantage when using botulinum toxin in a clinical setting. This is an advantage because, if there were any overtreatment of a muscle or even involvement of the incorrect muscle, the error resolves on its own with no long-term untoward effects. The disadvantage with this therapy is that it is not permanent and needs to be repeated approximately every three months.

|

|

Fig. 2. Hemifacial spasm is characterized by unilateral, periodic, tonic contractions of the facial muscles used in expression. Click image to enlarge. |

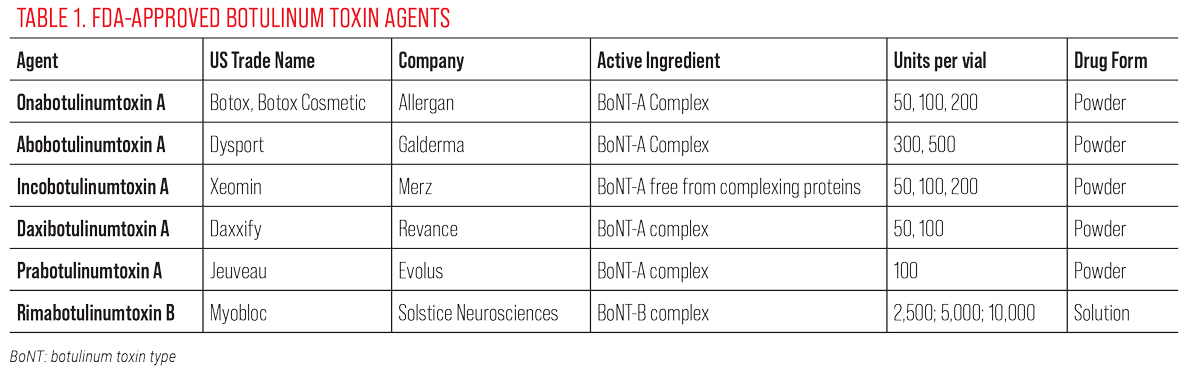

There are currently six FDA-approved neurotoxins (Table 1). All these agents can be used interchangeably, but it is important that the unit dosing is adjusted accordingly if the clinician uses various neurotoxins. It is probably most prudent for the clinician to get familiar with one or two of these agents and build proficiency with these before trying to mix and match multiple agents. Not all the agents are unit-to-unit equivalent and some have other subtleties that would affect patient outcome. For instance, abobotulinumtoxin A has a faster onset of action with a median time of onset of two or three days.12 On the other hand, daxibotulinumtoxin A has a longer duration of action with a median duration of 24 weeks. Therefore, dilution, dosage and injection points are the most critical considerations for the final clinical outcome.

Facial Dystonias

Benign essential blepharospasm (BEB) are bilateral involuntary spasms of the orbicularis oculi, procerus and corrugator musculature (Figure 1). BEB usually begins in individuals aged 50 to 70 with a mean age of onset of 56 years.5 Almost two-thirds are women. The spasms are so frequent and severe that they can result in functional blindness in up to 12% of patients.10 Meige syndrome (idiopathic orofacial dystonia) is when BEB is associated with intermittent lower facial movement. It can affect the patient’s speech and may cause involuntary chewing, lip pursing and trismus (lockjaw).5 Hemifacial spasm is characterized by unilateral, periodic, tonic contractions of the facial muscles of expression (Figure 2). Hemifacial spasm may be caused by a cerebellopontine tumor, or more commonly by microvascular compression or irritation of the facial nerve by an aberrant artery in the posterior fossa. All these patients must undergo neuroimaging.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Procedural Technique

Prior to the procedure, educate the patient and explain that botulinum toxin is a natural substance that, when used in the standard medical dosage, does not cause botulism or poisoning. Let them know it is administered via a few tiny injections and the treatment is simple, quick and minimally invasive. There is no downtime for the patient and, although the effect is not permanent, any overtreatment wears off, and future injections can be adjusted to obtain a more desirable clinical result.

The equipment needed includes:

- Topical anesthetic drops (i.e., tetracaine or proparacaine).

- Alcohol pads for cleaning the tops of the vials and for the patient’s skin.

- Gauze for any potential bleeding.

- A sharps container.

- A 1mL tuberculin syringe with a 30-gauge needle for the intramuscular injections.

- A 3mL syringe with an 18- or 20-gauge needle for reconstitution of botulinum toxin.

- A vial of sterile preservative-free 0.9% sodium chloride to reconstitute the botulinum toxin powder.

|

|

Fig. 3. Injection sites (depicted as an “X”) for benign essential blepharospasm-always done bilaterally. Procerus and corrugator musculature not labeled. Photo: Selina McGee, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Except for rimabotulinumtoxin B, which comes prepackaged as a solution, all the other neurotoxins come in a powder form. Therefore, they will need to be reconstituted by the clinician before they can be used. The neurotoxin agent being used and the reconstitution volume will provide the specific dilution. Always follow the manufacturer’s recommended dilution rates. As an example, for onabotulinumtoxin A, to obtain a dosage of 4.0 units for every 0.1mL to be injected intramuscularly, 2.5mL of 0.9% sodium chloride will need to be injected into the 100-unit vial of this neurotoxin.

Do not agitate the reconstituted neurotoxin either while injecting the sodium chloride into the neurotoxin-containing vial or after the injection is completed. It is recommended that the diluted neurotoxin be used within seven hours of reconstitution; however, studies have shown that the medication can be stored in a refrigerator between 2° C to 8° C for up to four weeks and still maintain up to 87% potency.15

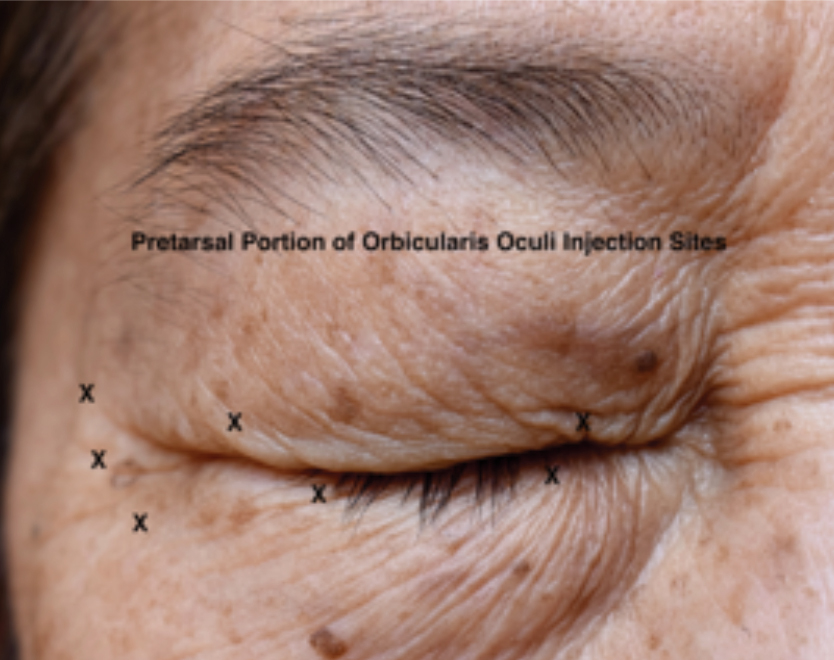

After the topical anesthetic eye drops have been applied, the patient is positioned and slightly reclined. This allows the clinician to adjust the height and angle of the patient. For BEB, injections should be given bilaterally, using the reconstituted neurotoxin that has been drawn up into the tuberculin syringe and using the 30-gauge needle. The initial injection sites should include the medial and lateral pretarsal orbicularis oculi of the upper eyelid and the lateral pretarsal orbicularis oculi of the lower eyelid (Figure 3). From 2.0 units (0.05mL) to 4.0 units (0.1mL) is administered in each injection site depending on the severity of the spasms. Since the skin in this location is very thin, insert the needle just below the skin surface and administer this injection subcutaneously in order to avoid inactivating the levator muscle, which lies immediately beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle and septum.

Injecting the levator muscle will cause blepharoptosis. The lateral canthal aspect of the orbicularis oculi muscle is also treated with one to three injections at or just lateral to the orbital rim.14 The procerus and corrugator/depressor supercilii muscle complex make up the glabella. Inject 4.0 units (0.1mL) intramuscularly centrally into the procerus muscle and two injections in each corrugator/depressor supercilii complex. One injection is given in the medial (body) aspect of this muscle complex, and the other in the lateral (tail) aspect. Lateral corrugator injections should be placed at least 1cm above the bony supraorbital ridge.

|

|

Figs. 4 and 5. At top, injection of botox in the central upper lid in the pretarsal portion of the orbicularis. A 30-gauge needle on a 1cc syringe is being used. At bottom, injection of botox along the temporal aspect of the orbicular muscle. Notice the shallow approach of the needle to the injection site and the wheal of medication being injected very superficially just below the skin. Click image to enlarge. |

In hemifacial spasm patients, all injections are administered only on the involved side. The same injection sites as would be administered for BEB are used. In addition, injection into the zygomaticus major, zygomaticus minor and risorius would also need to be performed. Document the specific neurotoxin and dilution used.

The treatment form should have a facial diagram where a pictorial account of the injection pattern and dosing can be recorded. This can then be referred to on subsequent visits to adjust the location and dosage of the injections to obtain the desired result.6

Post-op and Follow-Up

Instruct the patient not to lie down for several hours following treatment and to avoid manipulation of the injection sites. A potential side effect is post-injection blepharoptosis. It lasts for about two to three weeks. The patient can use either apraclonidine 0.5% or oxymetazoline 0.1% to activate Müller’s muscle. Since the blepharoptosis will resolve on its own, these medications can be used as a temporizing measure. Schedule the patient to return for repeat treatment in three months.

Dr. Skorin is a consultant in the Department of Surgery, Community Division of Ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Albert Lea, MN. In addition, he is an assistant professor of Ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, MN.

Dr. Lighthizer is the associate dean, director of continuing education and chief of specialty care clinics at the NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry.He is a founding member and immediate past president of the Intrepid Eye Society. Dr. Lighthizer’s full disclosure list can be found here.

1. Small R. Botulinum toxin injection for facial wrinkles. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(3):168-75. 2. Ahuero AE, Gross MP. Botulinum toxin and filler agents. In: Onofrey BE, Skorin L, Holdeman NR, (eds.). Ocular Therapeutics Handbook: A Clinical Manual, 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2020:660-3. 3. Hughes AJ. Botulinum toxin in clinical practice. Drugs 1994:48(6):888-93. 4. Binenbaum G, Chang MY, Heidary G, et al. Botulinum toxin injection for the treatment of strabismus, a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(2):1766-76. 5. Skorin L. Blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. In: Onofrey BE, Skorin L, Holdeman NR, (eds.). Ocular Therapeutics Handbook: A Clinical Manual, 4th Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters-Kluwer, 2020:617-9. 6. Berry MG. Botulinum Toxin in Clinical Practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2021. 7. McCann JD, Saulny S, Goldberg RA, Anderson RL. Essential blepharospasm. In: Chen WP, (ed). Oculoplastic Surgery: The Essentials. New York: Thieme, 2001:113-24. 8. Gallagher CJ. Basic science of Botox Cosmetic. In: Carruthers A, Carruthers J, (eds). Botulinum Toxin, 4th Edit. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2018:21-9. 9. Nestor M, Cohen JL, Landau M, et al. Onset and duration of abobotulinumtoxin A for aesthetic use in the upper face: a systematic literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(12):E56-83. 10. Salish N, Carruthers J, Kaufman J, et al. Overview of daxibotulinumtoxin A for injection: a novel formulation of botulinum toxin type A. Drugs. 2021;81(18):2091-102. 11. Lipham WJ. Treatment of blepharospasm, Meige’s syndrome and hemifacial spasm. In: Lipham WJ, (ed). Cosmetic and Clinical Applications of Botulinum Toxin. Thorofare NJ: Slack Incorp., 2004:37-45. 12. Carruthers J, Fagien S, Matarasso SL; Botox Consensus Group. Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6 Suppl):1S-22S. |