|

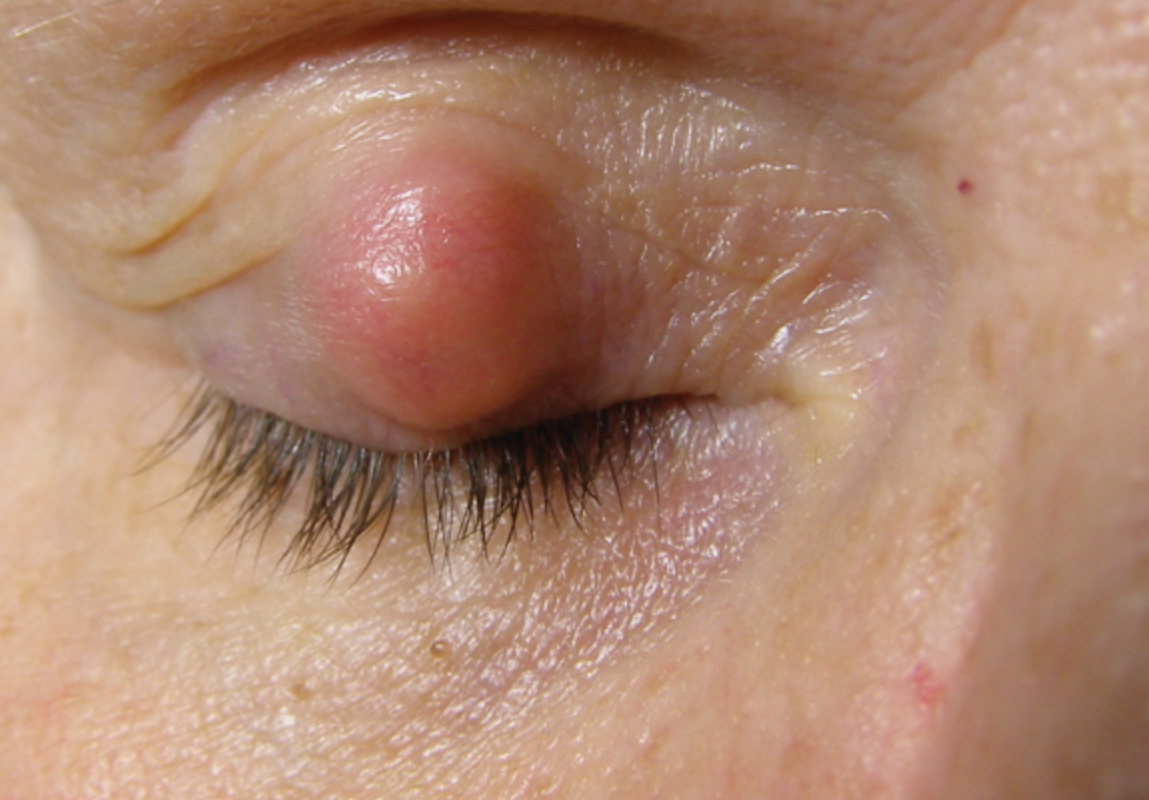

A chalazion is a benign, rigid, non-painful, non-infectious, granulomatous lesion caused by obstruction of a meibomian gland or gland of Zeis. These lipogranulomatous inflammatory lesions are filled with lipid deposits made up of epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes. A pseudocapsule made of connective tissue usually forms around the lesion. They present as round, enlarging nodules on the upper or lower tarsal plate (Figure 1).

Chalazia typically occur after internal or external hordeola, which are infections of the meibomian gland and gland of Zeis, respectively. There is no age or sex predilection, although they commonly occur in patients with chronic blepharitis and ocular rosacea. Clinical signs seen in association include eyelid margin telangiectasia, erythema and eyelash debris. A recurrent chalazion should be biopsied to rule out malignancies such as sebaceous gland carcinoma.

|

|

Fig. 1. Large chalazion. |

Treatment options for chalazia range from conservative to more aggressive approaches. These include warm compresses with or without oral antibiotics, intense pulsed light therapy, steroid injection, and incision and curettage.

When more conservative therapies or steroid injection fail to resolve a chalazion, surgical intervention with incision and curettage can be considered. This is a procedure that drains the contents of the chalazion and more likely avoids recurrence, as the entire lesion and capsule are removed. Cosmesis, discomfort and ptosis are all possible reasons why patients opt to have a chalazion removed. Practitioners may consider incision and curettage as initial therapy for larger chalazia, or after ineffectiveness of all other therapies. Patient preference may also dictate performing an incision and curettage earlier in the treatment paradigm.

|

|

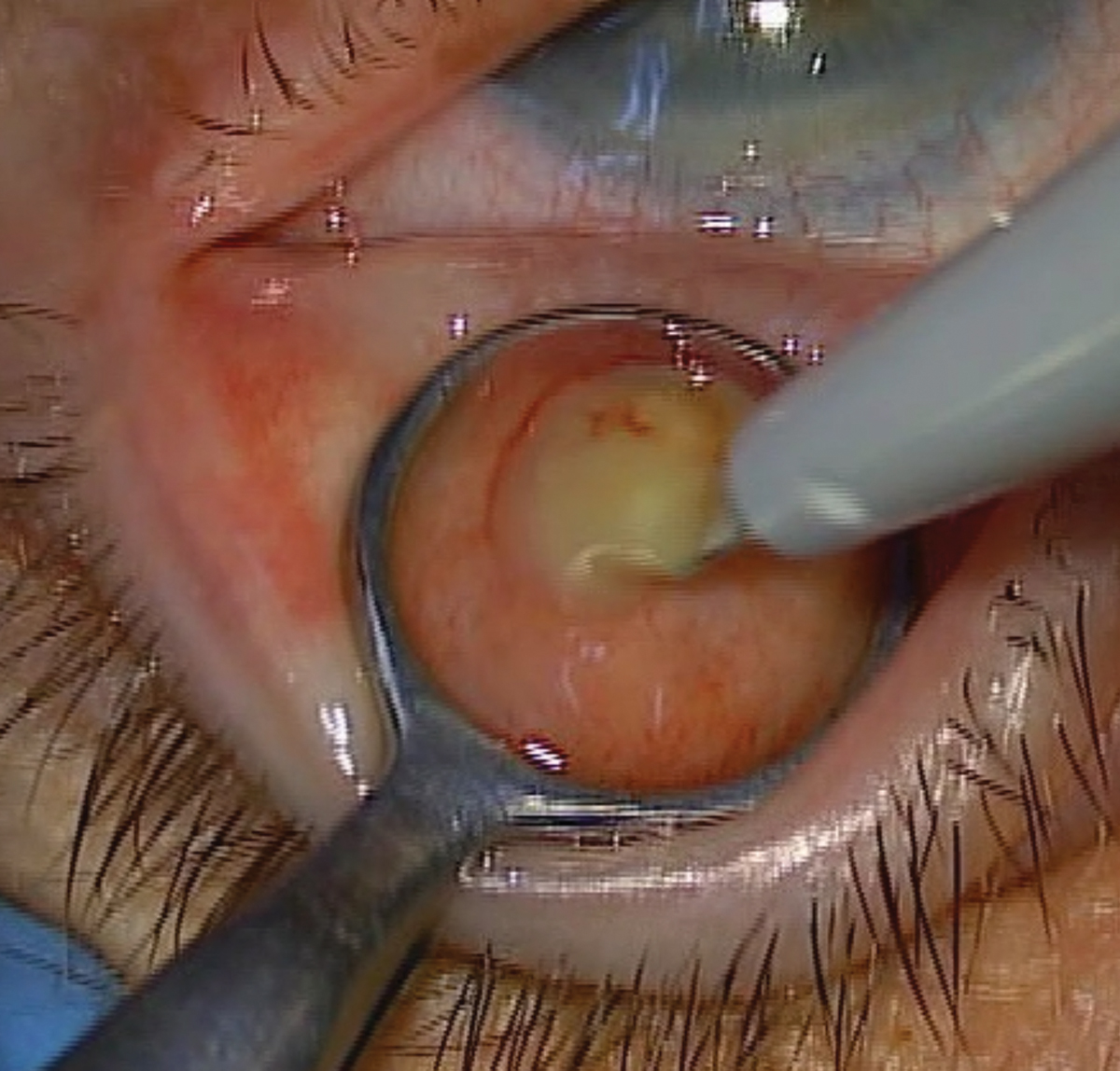

Fig. 2. Scalpel blade making a vertical incision (parallel to the meibomian glands) through the palpebral conjunctiva and into the meibomian glands. |

Procedural Technique

Let’s review how to perform an incision and curettage.

- Place the patient in a supine position and set up the surgical microscope or loupes.

- Instill topical anesthetic (proparacaine, tetracaine) into both eyes to minimize reflex lacrimation and the blink reflex, as well as keep the patient comfortable during the procedure.

- Clean around the lesion and skin—where the anesthetic will be injected—with an alcohol prep pad.

- Use a 30-gauge needle with bevel up to inject anesthesia (0.5%, 1% or 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 epinephrine) subcutaneously at a 10° to 15° angle around the chalazion. A bolus should be seen where the anesthesia was injected. Continue to inject as the needle is withdrawn. If additional anesthesia is needed, the patient will feel less pain if the needle is inserted in an area that was already anesthetized.

- Massage the anesthesia with a gauze pad or cotton-tipped applicator.

- Use a 10% povidone-iodine (betadine) swab stick to clean the lesion surface, ocular adnexal area and eyelashes to maintain asepsis. Povidone-iodine should remain on the skin for one to three minutes.

- Use a piece of gauze to remove any excess povidone-iodine if needed, with caution not to wipe uncleaned skin onto clean skin.

- Apply two to three drops of ophthalmic 5% povidone-iodine into the eye being treated. Let sit for 30 to 60 seconds before rinsing the eye with sterile saline.

- Use forceps to test the area to ensure it is anesthetized. If not, inject more anesthesia.

- Use a correctly sized chalazion clamp and insert around the lesion, with the open side toward the inner eyelid. The clamp should be the smallest clamp possible while still fitting around the chalazion.

- Slightly tighten the clamp, evert the eyelid and fasten the clamp tightly.

- Use forceps to test the exposed side of the chalazion (palpebral conjunctiva) to ensure it is anesthetized.

- If inadequate anesthesia is present on the palpebral conjunctiva, which commonly occurs, apply one to two Weck-Cel sponges soaked in 4% topical lidocaine directly on the chalazion. Hold each sponge on the lesion for approximately 30 to 60 seconds.

- Use the forceps to test the chalazion to ensure it is anesthetized. Ask the patient if they feel any pain or pinching. Pressure sensation is expected. Always ensure the lesion is fully anesthetized before performing the procedure.

- Using a blade scalpel, make a vertical incision into the chalazion. The incision should not be closer than 2mm to 3mm from the eyelid margin.

- Upon opening of the capsule, the chalazion contents may begin to express out of the lesion. (Figure 2). Use a cotton-tipped applicator to remove this content.

- Use a curette to remove the remainder of chalazion contents. A cotton-tipped applicator can also be used to apply lateral pressure to aid in this removal.

- Once the chalazion is drained, use the curette to traumatize the capsule. This helps avoid recurrence.

- A horizontal incision parallel to the eyelid margin to make a cross-shaped or “x-shaped” incision may also be needed depending on the size and chronicity of the chalazion and surgeon preference. If an “x-shaped” incision is performed, often times then a Westcott scissors will be used to excise fibrotic tarsal plate in the four “flaps” that are created from the two incisions.

- An optional injection of 0.1mL to 0.2mL of steroid (triamcinolone acetonide suspension) may be given to aid resolution.

- Remove the chalazion clamp. No sutures or patches are typically needed. There may be bleeding at the conclusion of the procedure once the clamp is removed as it was aiding in hemostasis. Rinse the eye with sterile saline and hold direct pressure with gauze to the closed eye to provide hemostasis. This may take five to 10 minutes.

- Apply ophthalmic tobramycin 0.3%/dexamethasone 0.1% ointment to the eye.

- Measure blood pressure and pulse.

|

|

Fig. 3a. Pre-op appearance of a patient prior to a chalazion incision and currettage. |

Follow-up

An operative report should be completed after every procedure that describes the steps taken to perform the procedure. Blood pressure and pulse is measured at the conclusion of the procedure due to the injection of epinephrine. An antibiotic/steroid combination ointment or antibiotic ointment is used three times a day for seven to 14 days to prevent infection and control inflammation. A one- to four-week follow-up appointment is typically scheduled to assess healing and chalazion resolution. All patients should be educated to return to the clinic sooner if signs and symptoms of infection arise.

Postoperative complications can occur, but fortunately, are fairly rare. Redness and mild pain are temporary during the post-op phase and will self-resolve once the area has healed. Bruising may occur from injection of anesthesia and typically resolves within two to three weeks. Eyelid notching results from excessive excision of the tarsus close to the eyelid margin, which again should be performed 2mm to 3mm away from the eyelid margin. A rare postoperative infection can be treated with oral antibiotics. Recurrence or a non-resolving chalazion may be re-treated with steroid injection or incision and curettage; however, take caution if malignancy, such as a sebaceous gland carcinoma, is suspected.

|

|

Fig. 3b. One month post-op appearance of the same patient showing complete resolution of the chalazion. |

Any recurrent chalazion in the exact same spot needs to be considered for possible sebaceous gland carcinoma, in which case, consider a biopsy. In rare cases, intravascular injections may lead to retrograde infiltration that could lead to a central retinal artery or vein occlusion. Two case reports have outlined individual patients who had a retinal and choroidal vascular occlusion after periocular injection of corticosteroid.1,2 This can be avoided by injecting with low pressure to minimize retrograde arterial flow.

Takeaways

Chalazion incision and curettage is a very rewarding procedure to perform, as patients do quite well with the procedure and usually have significant preoperative to postoperative improvement in the appearance of their eyelid (Figures 3a and 3b). A word of advice for the optometric physician that is just starting out doing in-office procedures: get a number of other procedures under your belt first (e.g., skin tag removals, seborrheic keratosis removals, sebaceous cyst removals, steroid injections for chalazion) to gain confidence in performing procedures on easier removals prior to starting chalazion incision and curettage.

Chalazia are fairly common eyelid lesions that most optometric physicians manage on a regular basis. A number of treatment options are available, with incision and curettage being a nice in-office surgical treatment option that typically delivers optimal results with high patient satisfaction.

The Next FrontierWelcome to Review of Optometry’s newest column, “Advanced Procedures.” This will be a bimonthly column intended for the optometric physician as a thorough review of an in-office procedure from as simple as punctal plug insertion to as complex as ptosis repair and everything in between. Indications, contraindications, preoperative considerations, postoperative management and potential risks and complications will be discussed for each procedure, with a special emphasis on procedural techniques. It is an exciting time in optometry and eye care. Technology continues to emerge and advance at every corner and in every space, procedures are becoming more efficient, more precise and more available to patients. We have seen exciting legislative expansion in optometry across the decades that has only increased access to high quality eye care by well-trained providers. Now with 10 states allowing optometrists to perform certain anterior segment laser procedures, and with more than 15 states allowing optometrists to perform certain types of injections, it is become increasingly evident that optometry will be at the forefront of office-based procedures over the next few decades. |

Dr. Patel is an assistant professor at the Oklahoma College of Optometry (NSUOCO). Dr. Patel is a diplomate of the American Board of Optometry and a fellow in the American Academy of Optometry.

1. Thomas EL, Laborde RP. Retinal and choroidal vascular occlusion following intralesional corticosteroid injection of a chalazion. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(3):405-7. 2. Yağci A, Palamar M, Eğrilmez S, Sahbazov C, Ozbek SS. Anterior segment ischemia and retinochoroidal vascular occlusion after intralesional steroid injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24(1):55-7. |