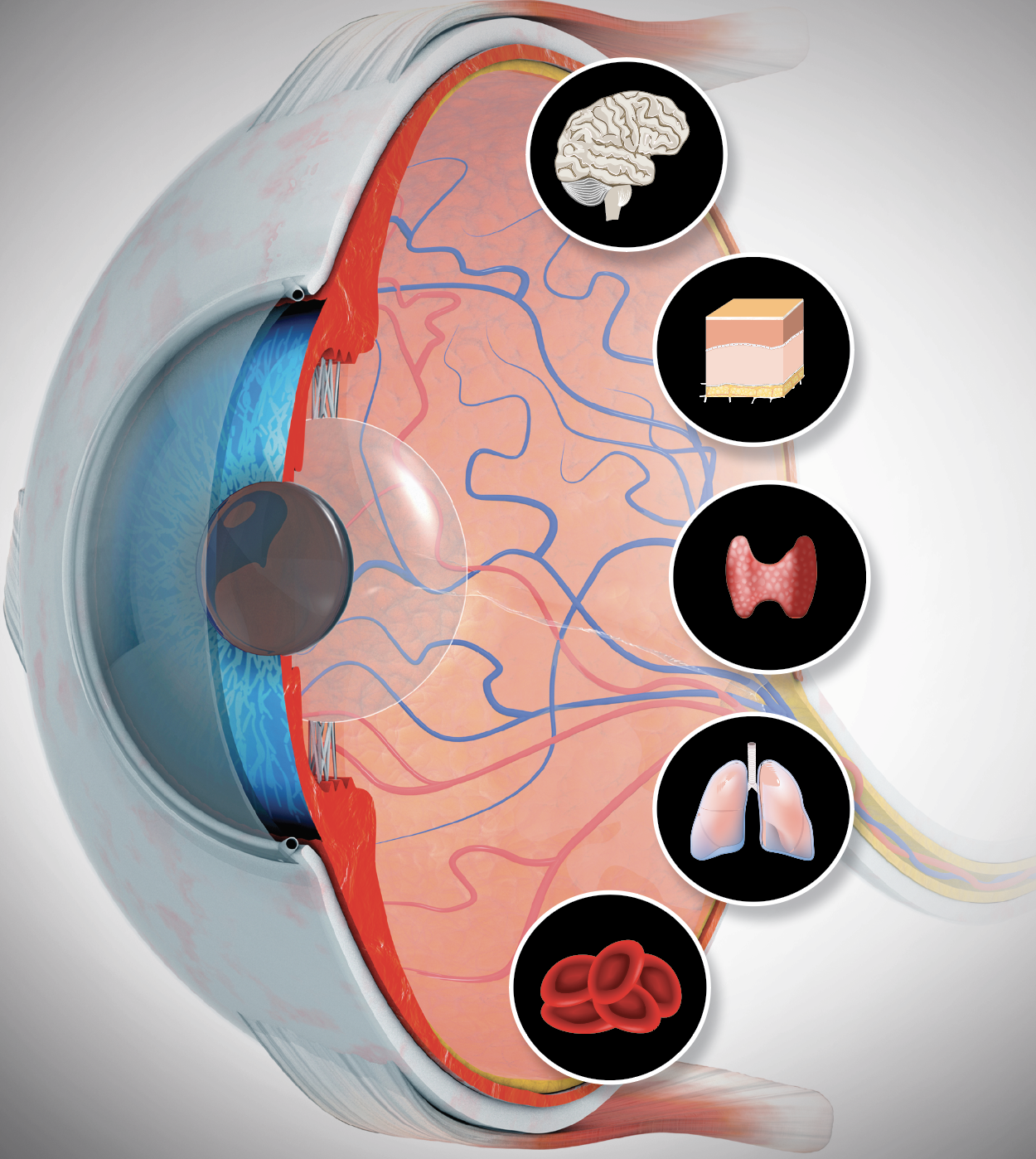

Seeing Systemic Disease within the EyeThis month in Review of Optometry, multiple ODs explain the connection between the eye and various systemic conditions, including hypertension, stroke, sleep disorders, COVID-19, diabetes, thyroid eye disease and more. Check out the other articles featured in the October issue:

|

Optometrists are tasked with managing the ocular health of patients, but the role of the OD does not end there. As primary eye care providers, you play a critical role in the overall health and well-being of your patients. Quite often, this means comanaging systemic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension with primary care and specialty physicians.

“None of us are ever going to see a pair of eyes in clinic that aren’t attached to the rest of the body,” notes James Fanelli, OD, of Cape Fear, NC. “What we are seeing in the eye is oftentimes just a manifestation of something happening elsewhere.” Some scenarios are obvious, as when a patient comes in with a known diagnosis, he explains, but frequently “they may not have a systemic diagnosis and we find something in the eye that indicates, for example, that they could be diabetic or have elevated cholesterol levels,” he continues. “As optometrists, we can then work very closely with the appropriate internal medicine specialist to get their condition under control to mitigate the risk of ophthalmic and systemic complications.”

Given the wide range of systemic conditions an OD may encounter in their practice, navigating this aspect of patient care is not a simple undertaking. In this article, we will delve into the nuances of comanaging common systemic diseases with providers outside of eye care as well as what the optometrist needs to know to provide comprehensive care for the whole patient.

|

|

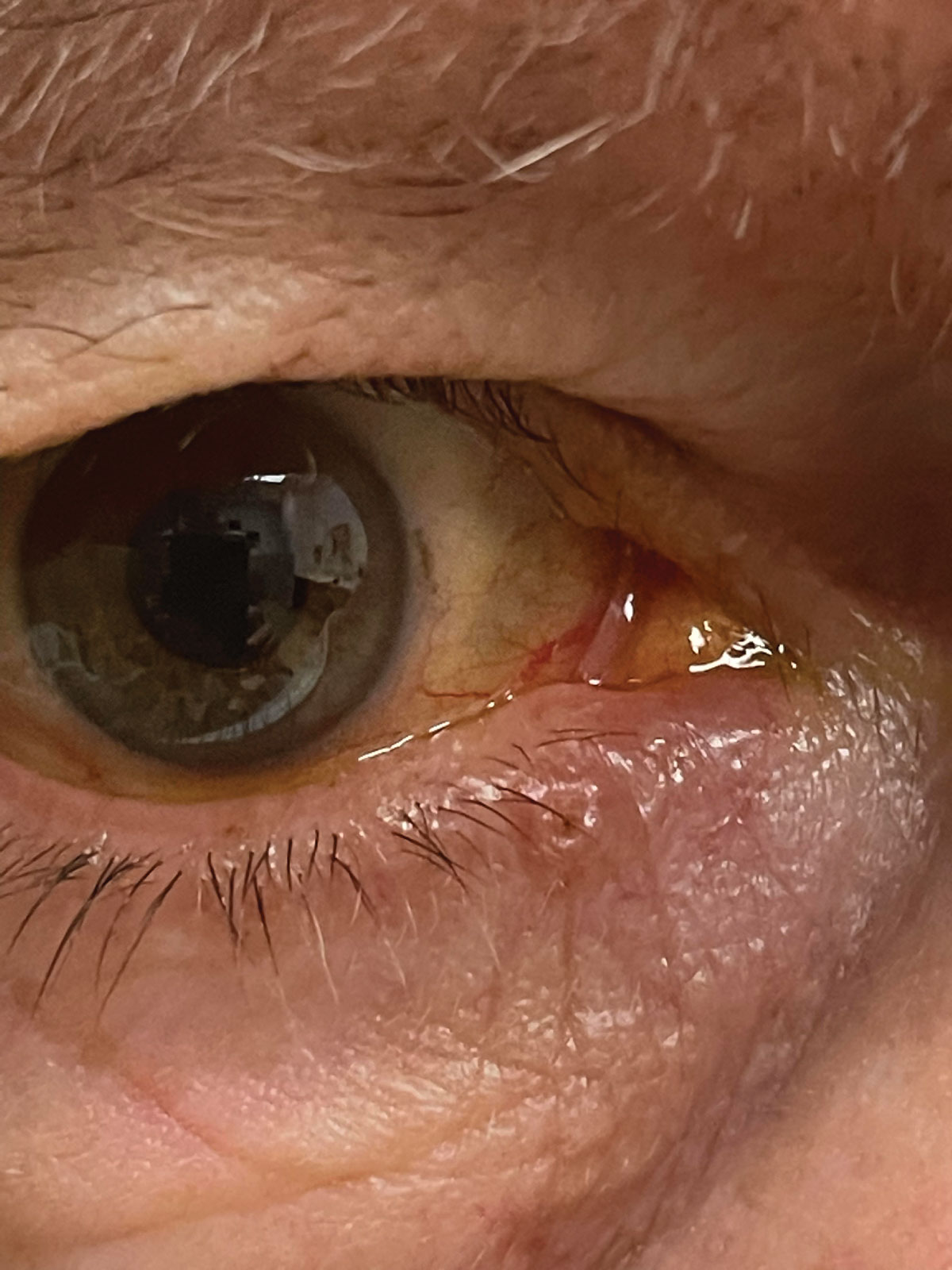

Suspicious non-healing, ulcerated skin lesion along the lower lid margin that the patient reported as becoming slightly larger over several months. Referral was made to oculoplastic surgeon to confirm diagnosis and necessary treatment of malignancy vs. benign lesion. Click image to enlarge. |

The OD's Role in Systemic Disease

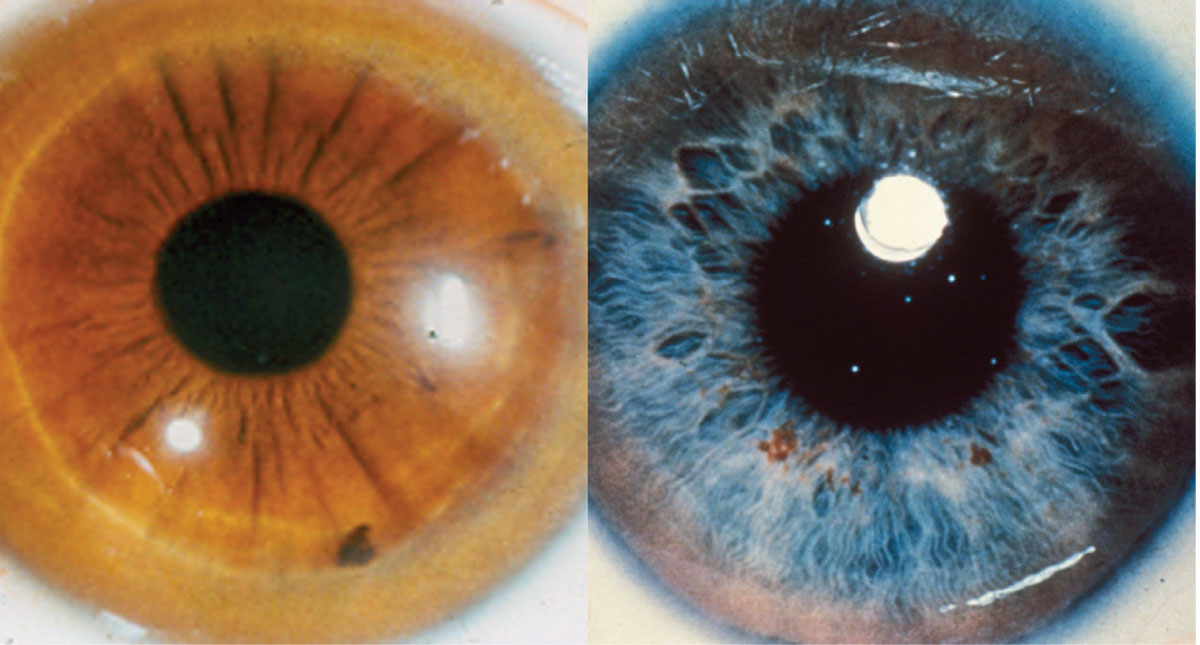

Dozens of systemic diseases are associated with ocular findings, and ODs are a key component of the diagnosis and comanagement of these conditions, given their role on the front lines of care. Virtually every portion of the optometric exam may provide clues to some sign of systemic disease, according to Joseph Shovlin, OD, of Scranton, PA, who notes that some signs and symptoms are subtle and can go undiagnosed without careful scrutiny.

Dr. Shovlin recommends starting with a detailed ocular and systemic history that should include attention to family history then moving through the typical optometric exam sequence. There are a number of commonly seen ocular signs that may signal systemic conditions.

“Starting with an external examination that may show eyelash ptosis/floppy eyelid syndrome, you’ll want to consider if additional evidence points to sleep apnea,” Dr Shovlin says. “Special attention may be indicated to seemingly benign conditions,” he advises. For instance, simple myokymia that spreads beyond the lid warrants imaging to rule out a compressive lesion at the stylomastoid foramen. Facial involvement may signal Lyme disease.

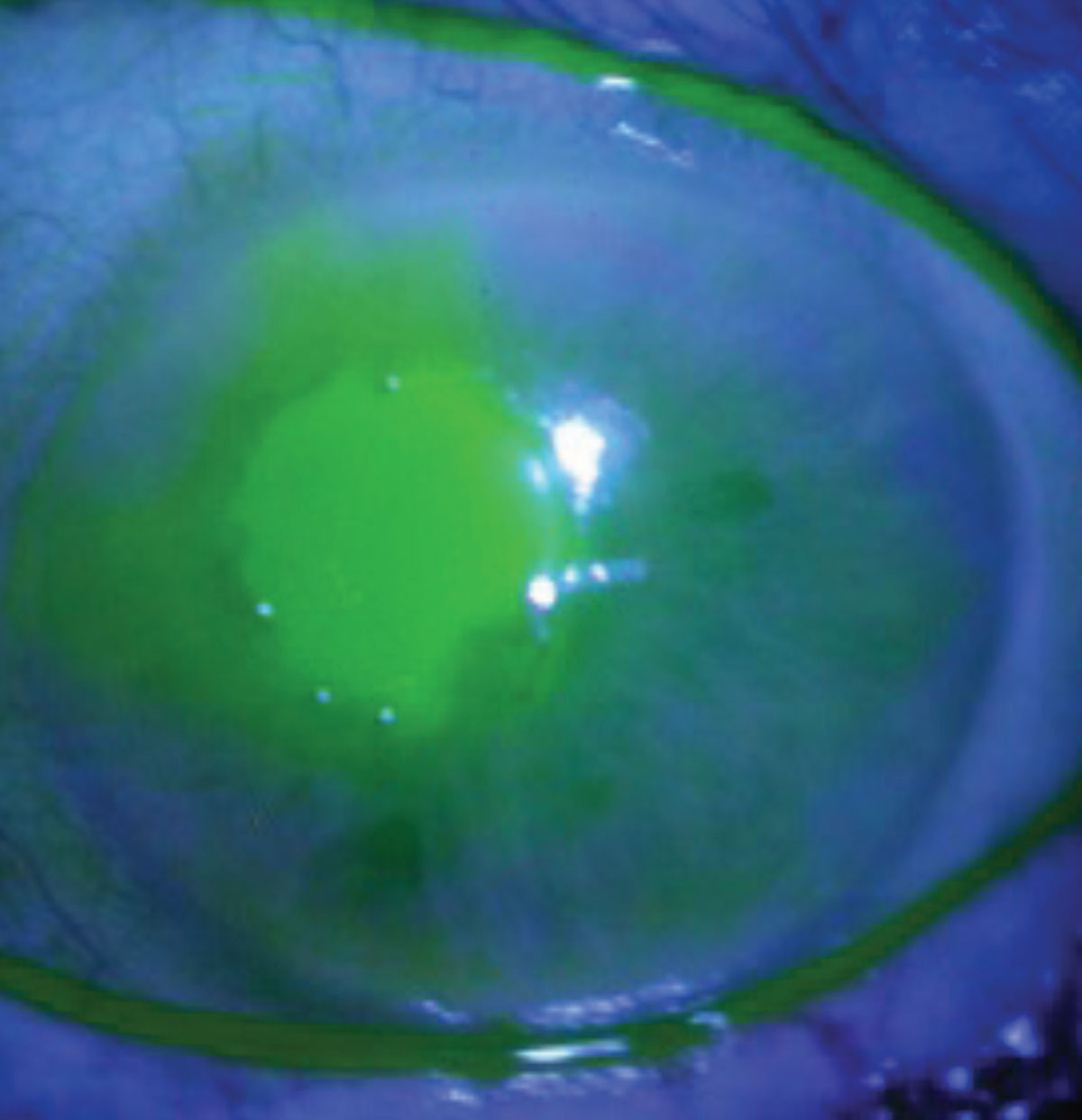

“The cornea and conjunctiva may hold a treasure trove of valuable information that can lead to a systemic query,” Dr. Shovlin continues. “Quite commonly seen is band keratopathy, suggesting a phosphorous renal clearance decrease specifically pointing to kidney problems or even parathyroid (PTH) dysfunction, necessitating PTH testing.”

Optometrists must be able to detect the tell-tale signs or symptoms both in patients who have been diagnosed with a systemic disease as well as those who have not. “As primary healthcare providers, we should take an active role in management of patient’s systemic conditions and lifestyle choices,” says Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, of Germantown, TN.

The first step, he explains, is to not just ask questions like, “Do you have diabetes?” and wait for a “yes” or a “no” answer and go to the next question. “If the answer is a ‘yes,’ we need to ask about level of management, adherence to the regimen and follow-ups with other healthcare providers,” Dr. Rafieetary explains. “If the answer is a no, then we need to investigate thoroughly.”

This includes, according to Dr. Rafieetary, asking questions like these: “When was the last time you had a physical? What was the doctor’s name? Did you follow-up for your test results? Do you know what your blood sugar numbers were?”

While he acknowledged these questions can sound obtrusive, their responses will help ODs better understand the patient and how involved they are with their health. A major component of managing any condition is education the patient. This is an area ODs can—and should—take an active role.

Below, we will discuss a few systemic conditions and the role an optometrist can play in their diagnosis and management.

• Cardiovascular diseases. Conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, carotid occlusive disease and related issues can manifest in a variety of ways in the eye. This may be as basic as corneal arcus, hypertensive vascular changes in the retina, various presentations of retinopathy or ocular ischemic syndrome, or include issues such as artery or vein occlusion, ischemic optic neuropathy or cranial nerve palsies, according to Sara Weidmayer, OD, of Ann Arbor, MI.

“We also commonly hear of transient monocular vision loss (TMVL): this is a form of transient ischemic attack (TIA),” she says. “Around 25% of patients with TMVL also had a concomitant stroke, and the highest risk of having a stroke after TIA is within 48 hours, so our swift and appropriate action in getting these patients emergency stroke workups and subsequent stroke risk management is crucial.”

These patients can sometimes have giant cell arteritis (inflammatory source), carotid stenosis or aortic valve calcification (embolic source) or atrial fibrillation (thromboembolic source), so directing a cardiovascular workup is key, according to Dr. Weidmayer.

Kelly Malloy, OD, of Philadelphia also emphasized the importance of checking blood pressure. “As you know, blood pressure is analogous to intraocular pressure (IOP). If you are seeing a patient for their yearly eye exam, you would always check IOP, even if they are followed every three months by a glaucoma specialist.” If you found the IOP to be elevated, she argues, you would communicate that to the glaucoma specialist.

“We need to think about blood pressure in the same way. It should be measured on every patient encounter and we should be communicating with the primary care physician (PCP)/specialist who is managing their blood pressure if we find it to be poorly controlled,” she recommends.

Optometrists will often see patients on medicine for blood pressure and cholesterol, notes Dr. Fanelli. “This will clearly manifest, completely asymptomatic and very normally, as atherosclerotic retinopathy or perhaps very mild hypertensive retinopathy, but with both of those conditions, as the disease progresses the ophthalmic retinal findings and the retinal vascular become much more pronounced,” he explains, while emphasizing the importance of retinal photography in these cases.

“This can make a significant difference for our patients long term,” he elaborates. “Even in those who are currently managed for hyperlipidemia, evidence of disease progression in the end organ we examine—the eye—warrants a conversation with their internist to perhaps drive lipids down even further. That is a valuable piece of information for the internist to know.”

“A careful evaluation of the retina and specifically its vasculature may identify acute or longstanding hypertension concerns,” adds Dr. Shovlin. “Of course, diabetic eye related changes may be evident as well even in undiagnosed diabetics. Early hypertensive retinopathy shows retinal arteriole narrowing/focal constriction and can show exudate, edema and even optic nerve swelling in more advanced disease.”

|

Band keratopathy seen in a patient with kidney disease. Click image to enlarge. |

• Diabetes and other retinal manifestations. ODs should be on the lookout for signs of the systemic component in patients with negative history, Dr. Rafieetary recommends. “For those with known diagnosis, historical perspectives, such as duration of disease, level of management, presence of complications and comorbidities such as renal failure, past CVA, hypertension, lipid disorders, sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, obesity and smoking are all important in the risk assessment of presence of diabetic retinopathy, as well as potential progression and prognosis.”

One out of every 10 patients you see have diabetes and three or four out of 10 are pre-diabetic, according to Dr. Rafieetary, who notes that diabetes can also have non-retinal ocular effects such as refractive shift. This should raise the suspicion to further dissect the issue.

While patients may be resistant to dilation, Dr. Rafieetary underscores the importance of performing a dilated fundus exam on all patients. This, he notes, becomes even more imperative among patients with certain symptoms or conditions with potential retinal involvement.

“Use of imaging technologies plays a critical role as well,” Dr. Rafieetary adds. “However, ODs should keep in mind the limitations, sensitivity and specificity of these tests. For example, OCT is an excellent test for detection of diabetic macular edema. However, it is not to be substituted for a comprehensive retinal examination.”

|

|

Neurotrophic keratopathy secondary to herpes zoster infection. Click images to enlarge. |

• Neurologic conditions. There are a number of neurologic diseases that can affect vision and cause various symptoms ranging from dry eye and double vision to blindness. Systemic neurologic conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s can have ocular manifestations and, following a stroke, patients often face visual problems that stem from neurologic damage.

“Be sure to use the tools in your toolbox to your full capacity,” says Dr. Malloy. “As the eye doctor, you are the only member of the patient’s health care team to have and be able to access visual fields and OCT. Remember that these are not just for glaucoma.” When patients complain of new-onset headaches or subjective visual disturbances, run visual fields and OCTs, Dr. Malloy advises. “This should be done before referring to the PCP or neurologist for headache management.”

Abnormalities on these tests, she adds, could help identify an underlying issue that may otherwise be incorrectly labeled as migraine. “For example, uncovering a subtle homonymous hemianopia in such a patient could demonstrate that this person needs neuroimaging that might uncover a brain mass,” says Dr. Malloy, who recommends all optometrists re-familiarize themselves with performing a cursory neurologic examination.

“You test cranial nerves II, III, IV, and VI or a regular basis, but how often do you check the other eight cranial nerves? Your ability to do so may help identify and localize a causative etiology for a patient’s symptoms or clinical presentation,” she advises. “Do you ever test a patient’s strength and sensation, or assess their gait? These can not only help localize an etiology for their ocular signs and symptoms but also help you identify non-ocular issues for which the patient would benefit from neurologic consultation.”

Dr. Malloy also emphasizes the importance of assessing a patient’s mental status. When it’s warranted, a simple, mini-mental status exam—in addition to the other aspects of a neurological examination—can help determine when a neurologic referral may be indicated for early neurodegenerative disease or other causes of dementia.

“Be sure to look at the patient as a whole and not just a pair of eyes,” she says. “Work to your capability of being an integral part of the patient’s health care team. This is applicable to all areas of systemic disease, not just neurologic issues.”

• Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. There are a number of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases that can impact the eyes and vision, such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Other conditions an OD may come across in the clinic include spondyloarthropathies, sarcoidosis, Sjögren’s syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease.

These conditions can present with a variety of ocular manifestations. For instance, lupus can lead to eye-related conditions such as optic neuropathy and vascular lesions. Patients may present with symptoms such as dry eyes, blurred vision and light sensitivity. A common symptom of rheumatoid arthritis is dry eye. Other conditions associated with this condition include scleritis and uveitis. In fact, there is about a 50% chance that patients with scleritis have an associated autoimmune condition.

As always, it’s important to keep a patient’s medical history in mind throughout the entirety of your exam as well as recognize the signs of any potentially underlying conditions.

• Other conditions. There are a plethora of other conditions that ODs will likely see in their practice. One example is obstructive sleep apnea, an often underdiagnosed condition, according to Dr. Rafieetary, who notes that this condition has ocular and non-ocular signs that ODs should know about and have a conversation with the patient if suspected. “This is associated with floppy eyelid syndrome, and it’s remarkable how even a very basic eye exam and symptom screening can prompt a sleep study and obstructive sleep apnea diagnosis,” adds Dr. Weidmayer.

Another area where optometrists can have an impact is dermatologic conditions, notes Philadelphia’s Marc Myers, OD. “We see our patients, hopefully, on a routine basis, and by doing so we can follow up on skin diagnoses and skin cancers. Most skin cancers affect people above the shoulder.”

When Dr. Myers examines a patient, he is not only assessing their eyes, but also looking at the skin of their head and neck. He will ask questions such as, “Do you have a history of involvement with a dermatologist? When was the last time you were there? Are you using sun-safe techniques like staying out of the sun and using sunscreen?” Dr. Myers will then communicate with the dermatologist directly if he finds anything suspicious that could warrant further examination and testing.

Dr. Shovlin, who recently had a patient with a suspicious nose lesion that turned out to be basal cell carcinoma, emphasizes the importance of looking under the face mask.

Regardless of the condition, an optometrist must feel comfortable to pick up the phone and call the appropriate provider, whether that is the PCP or a specialist, Dr. Myers says. “We have to share clear and detailed findings, so that our comanagement partner understands the severity and needs of the patient,” he notes. “This also helps confirm that the importance of following through with the recommended care has been communicated to the patient.”

Determining Referral UrgencyAs discussed, optometrists should be prepared to refer to a specialist when deemed necessary. However, most specialists, and especially neurologists, are often booked out at least three months, if not longer. It is up to the OD, according to Dr. Malloy, to determine the urgency of the referral. “Keep in mind that there is a difference between wanting your patient to be seen sooner so you feel better about shouldering the responsibility and needing your patient to be seen sooner because you know they have something of legitimate concern,” she advises. “However, if your patient does have that more urgent issue, you will need to call the office and speak with a nurse or doctor to explain why you feel your patient needs to be seen more urgently.” As your patient’s advocate, if you feel they are not receiving the necessary care in the appropriate timeframe, be persistent, Dr. Malloy urges. “When needed, you can call the hospital emergency department and discuss the possibility of sending the patient to them to initiate any emergent work-up and/or treatment if you know what is needed.” This is why keeping up with the literature and new practice guidelines is critical. “For example, the latest practice guidelines now clearly state that we should be managing all patients with acute vision loss (even if transient) or acute retinal artery occlusion the same as we would manage any new-onset stroke, with immediate referral to an emergency department at a hospital with a dedicated stroke center,” Dr. Malloy notes. |

Patient Care Across Disciplines

Effectively comanaging systemic conditions with healthcare providers outside of eye care requires strong relationships based on mutual respect and trust. Taking the time to foster connections with local PCPs and specialists will go a long way when the need for collaborations arises.

Communication is key. When the OD is the first to suspect a systemic condition, it is important to reach out directly to the appropriate provider.

Dr. Shovlin prefers a phone call. If you are referring to a specialist, the PCP should always be kept in the loop, he advises.

“In some cases,” says Dr. Rafieetary, “it is best to send the patient to the local ER with a call to the ER physician ahead of time,” particularly if dealing with acute and life-and vision-threatening situations such as malignant hypertension, central retinal artery occlusion, papilledema or ischemic optic neuropathy with suspicious of giant cell arteritis. “It may not even be unreasonable to call EMT to transport the patient,” he advises.

In cases where specialty care hasn’t been established, ODs shouldn’t hesitate to make a referral to a specialist or subspecialist, according to Dr. Rafieetary. However, he notes, there are instances where a PCP referral may be required.

“In our area, most rheumatologists do not accept patients from our office if we suspect an autoimmune disease,” he explains. “They want an internist to at least evaluate the patient and try to manage their care. We have had to establish working relationships with a handful of our area rheumatologists to be able to send the patient directly to them.”

How you communicate with other providers is also crucial. “Although EHRs have made it simpler to send a report to other healthcare providers (HCPs) and we should take advantage of this, you cannot always trust that the note or the report gets into the hands of the HCP you were trying to send information to,” advises Dr. Rafieetary. “Sometimes it is easier to make the patient an appointment or rely on them to make an appointment for themselves, or present to a pre-existing appointment with a copy of your test results or a note you need to convey to other HCPs.”

Working with other providers can sometimes be challenging, and Dr. Shovlin notes that there will be occasions where you may be met with some resistance, especially if you are recommending specific testing. “Don’t be deterred,” he says. Recalling a recent case, he explains, “I sent an elderly woman who experienced an artery occlusion for a stroke protocol to the ED along with a note for obtaining an ESR and CRP, in addition to what would normally be done on ED presentation.” About four hours later, Dr. Shovlin received a phone call at home from a first-year emergency physician admonishing him for suggesting such testing on “her” patient.

“She refused to do a simple sed rate and when I called the ED the next morning, I spoke to another physician who obtained the necessary test only to report a sed rate of 82 later that day,” he continues. “Steroids were immediately started and a temporal artery biopsy was done in our ambulatory surgery center later that week showing inflammation consistent with giant cell arteritis.”

Effectively comanaging with other physicians requires confidence as well as willingness to learn and ask questions, when needed. “Very clear and specific referrals are key. Remember that you are the eye specialist, and other healthcare providers in different specialties depend on you to communicate what is happening with the patient, why you referred them and what specifically you want them to look for,” Dr. Weidmayer, says.

“If you have a specific problem that requires a specific test, state exactly what needs to be done. If you don’t know exactly what to do, that’s OK—but talk to somebody who does,” she adds. “We should all know enough to understand the level of urgency of the condition at hand. Don’t be afraid to pick up the phone and talk to someone to ensure you’re making the appropriate decisions.”

ODs must also recognize that providers outside of eye care don’t always understand what optometry is and the full scope of what the specialty is capable of, notes Dr. Fanelli. “Having confidence in—and clearly articulating—your expertise is an important aspect of comanagement,” he says. “Building relationships and mutual trust in one another’s abilities is the key component of success. You want to work the providers who understand and value what you bring to the table as an optometrist.”

|

Experts advise optometrists to be vigilant for clinical signs of sebaceous gland carcinoma. Click image to enlarge. |

Another key component of systemic disease comanagement is medication. For the OD, that means contending with potential ocular side effects. However, given the growing list of drugs that can affect the eye and vision, this can prove challenging.

“There are many medications that have an effect on the eye. Unfortunately, some have potential to cause irreversible vision loss,” according to Dr. Shovlin, who advises ODs to “always alert any provider who has any direct effect in prescribing such medication with any concerns you have after you have examined your patient.”

Quite often, Dr. Weidmayer explains, the need for the systemic medication is greater than the risk of ophthalmic side effects. “However, we certainly still have a say and can communicate that with the prescribing physician.”

One example Dr. Weidmayer gives is Plaquenil use. She finds that patients on this medication are taking a dose that exceeds the maximum recommended 5mg/kg/day in regard to retinal toxicity risk. “This typically happens as elderly patients lose weight and their dose is not adjusted accordingly,” she says. “I regularly talk with our rheumatologists and ask them to trim the dose—which usually gets trimmed from 200mg BID to 300mg/day equivalent (either 300mg/day or 400/200 per day alternating for a 300mg/day equivalent).

“Another nuance I tend to run into in Plaquenil monitoring is pre-existing or developing macular disease,” she continues. “I ask the rheumatologist to explore alternatives to Plaquenil when there are any macular issues present that would make it difficult for me to discern whether the patient was developing Plaquenil toxicity over time.”

Any evidence of early macular toxicity is a hard stop for Plaquenil, according to Dr. Weidmayer. “Rheumatology has never given me pushback on that, since permanent central vision loss would be the end result if the patient remained on it,” she explains.

Patients with pachychoroid spectrum disease (e.g., CSCR) should avoid systemic steroids if possible, Dr. Weidmayer advises, while acknowledging that this cannot always reasonably be avoided, since steroids are used for such a wide range of conditions.

“In patients with a CSCR history, I typically alert the healthcare team that steroids of any kind should be avoided if possible and ask that they refer the patient to me if any are started so I can evaluate them,” Dr. Weidmayer explains, while noting that this is similar to the approach she takes when managing steroid-sensitive IOP patients.

For example, she has a patient with very steroid-responsive IOP who gets semi-regular intra-articular steroid injections. His orthopedic/physical medicine and rehabilitation physician has been made well aware that his IOP is steroid-sensitive, so Dr. Weidmayer is alerted several weeks before any scheduled injection.

“I send the patient some Cosopt and he comes in at scheduled intervals for IOP checks thereafter until we can stop the Cosopt again,” she says. “This is not an unmanageable situation, we just all need to be on the same page.”

There are a plethora of other medications that an OD may come across in their practice. One example is sildenafil (Viagra). “This and other PDE-5 inhibitors have been associated with dose-dependent, reversible color vision abnormalities, but also with more concerning non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION),” according to Dr. Weidmayer. Risk vs. benefit calculations should be discussed with such patients on an individual basis and include considerations of possible comorbid health conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia) and relevant ocular history (e.g., prior NAION in the other eye, binocular/monocular status, other eye disease), she notes.

“I will typically simply alert the prescribing physician that PDE-5 inhibitors are associated with an increased risk for NAION and summarize the discussion I had with the patient as a launching point for the PCP to consider discussing risks/benefits with the patient,” Dr. Weidmayer explains.

Another medication ODs should be aware of is pentosan polysulfate (Elmiron), which is used for patients who have interstitial cystitis. This medication can cause irreversible central vision loss, so close monitoring is necessary. “Pre-emptively communicating with urologists in your local community about the ocular risks of this medication is a great idea; that way, prescribers will send patients to eyecare providers for appropriate screening,” suggests Dr. Weidmayer.

Recent evidence has shown that antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)—a newer class of targeted cancer therapy—can cause corneal deposits and microcysts, keratitis, conjunctivitis and optic neuropathy.

“With the explosion of the systemic therapies for almost every condition, it is impossible to remember or keep up with indications and adverse reactions of all things in the market. We also must keep in mind interaction with medications that we may prescribe,” Dr. Rafieetary says.

“In years past,” he notes, “we used to rely on PDR books, but once again the worldwide web and various apps have made it much easier for us to search or verify this information. One of my favorite apps is Medscape.”

|

|

The genetic disorder Wilson’s disease manifests in the eye as a Kayser-Fleischer ring.Click image to enlarge. |

Taking a Holistic Approach to Practicing Eye Care

With a host of systemic conditions and associated medications, it can feel daunting to play an active role in the diagnosis and management of these diseases. However, optometrists are in the perfect position to do so.

“So many systemic diagnoses have a bearing on how the eye works and can have direct consequences on ocular health,” notes Dr. Myers. “Sharing your knowledge and positioning yourself as a provider invested in your patients’ overall health is beneficial both for the community and your own practice—opening the door for future comanagement and referrals to the practice.”

An aging population that has a growing need for primary eye care coupled with a looming shortage of ophthalmologists will make this even more important moving forward. “We’re going to be the gatekeepers that have to be aware of these medical diagnoses both for early detection of ophthalmic complications as well as ocular manifestations that indicate a systemic issue,” Dr. Myers says. “As optometrists, we have a multifaceted part to play to ensure our patients receive optimal and comprehensive care.”