|

A child with monocular visual acuity reduction, significant hyperopic anisometropia and a constant unilateral strabismus in the same eye most likely has amblyopia. If no relevant new symptoms arise and clinical findings remain unchanged, most clinicians will not suspect an ominous, hidden disorder such as an optic nerve tumor. As stressed in our August 2023 “You Be the Judge,” diagnosing amblyopia without anisometropia and/or without constant unilateral strabismus could prove to be disastrous. On rare occasions, visual acuity (VA) reduction could be due to myriad disorders in the same eye, including, but not limited to, constant unilateral strabismus and significant hyperopic anisometropia. The timely diagnosis of disorders such as an orbital or brain tumor may be complicated by the presence of the more benign and common disorders.

|

|

Axial MRI section through the orbital mass OD (on the left) and the normal optic nerve OS (on the right). Click image to enlarge. |

Case

The daughter of a physician was first examined by an eye clinician at age nine. Best-corrected VA at the time was 20/50 through +9.00D sphere OD and 20/25 through a +6.00D sphere OS. Pinhole testing did not improve the VA in either eye. The external exam was noted to be normal, including pupillary testing and confrontation visual fields. The fundus exam revealed slightly small optic nerve heads, right being smaller than the left. The foveal reflex was present in both eyes. The diagnosis was amblyopia in the right eye and glasses; contact lenses were later prescribed. No substantial change occurred over the next decade until automated visual fields were first performed and revealed a small inferior visual field defect in the right eye only. The patient was instructed to return in six months for a contact lens check and a repeat visual field.

At the next scheduled visit, she reported no new symptoms, and the best-corrected VA was still 20/50 OD and 20/25 OS with the same refractive error as previously. Visual fields were repeated with a Frequency Doubling Technology and an Octopus 1-2-3 perimeter. Both devices revealed minor loss in the inferior nasal quadrant in the right eye and a normal visual field in the left eye. Recognizing that amblyopes should not demonstrate a field loss, the primary eye clinician decided to refer the patient to a prominent neuro-ophthalmologist at a major academic medical center.

The neuro-ophthalmologist obtained a history of the patient requiring glasses since a very young age and noted that she never had 20/20 vision in the right eye. The patient denied worsening of vision in either eye or any other visual symptoms. The external exam was unremarkable, including confrontation visual fields. Motility and pupils were noted as normal. There was no red desaturation reported with the right eye. On cover test, a small hypertropia OD was observed. This exam revealed very similar refractive error measurements and best-corrected visual acuity measurements as previously recorded. Visual field testing with a Goldmann perimeter was notable for constriction with the I2e isopter in the right eye, especially inferiorly. The left field was normal. A dilated fundus exam revealed hypoplastic discs, smaller in the right eye. Intraocular pressures, on this and previous exams, were always normal.

The neuro-ophthalmologist concluded: “I believe the patient has a long-standing amblyopia of the right eye and she may have a small suppression scotoma with a slight hypertropia as well.” His plan was to re-evaluate the patient in six months and obtain neuroimaging if there was any change in visual status. The patient never returned to the specialist but followed up with her primary eye clinician. An exam a year later for new contact lenses and a repeat visual field demonstrated no change. The inferior field defect in the right eye persisted but did not worsen. Over a decade and a half, the patient developed conjunctivitis several times and was treated without incident by her primary eyecare clinician.

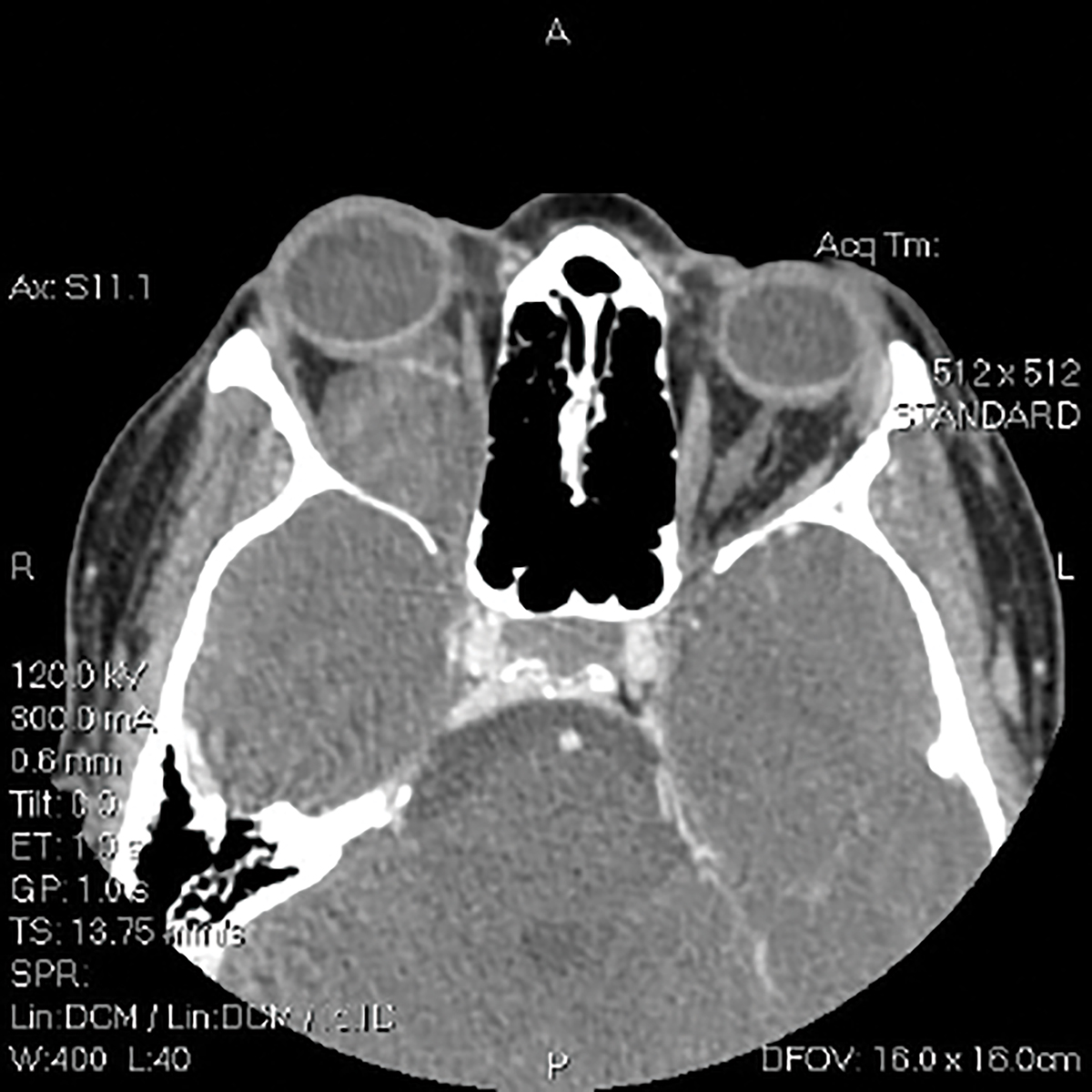

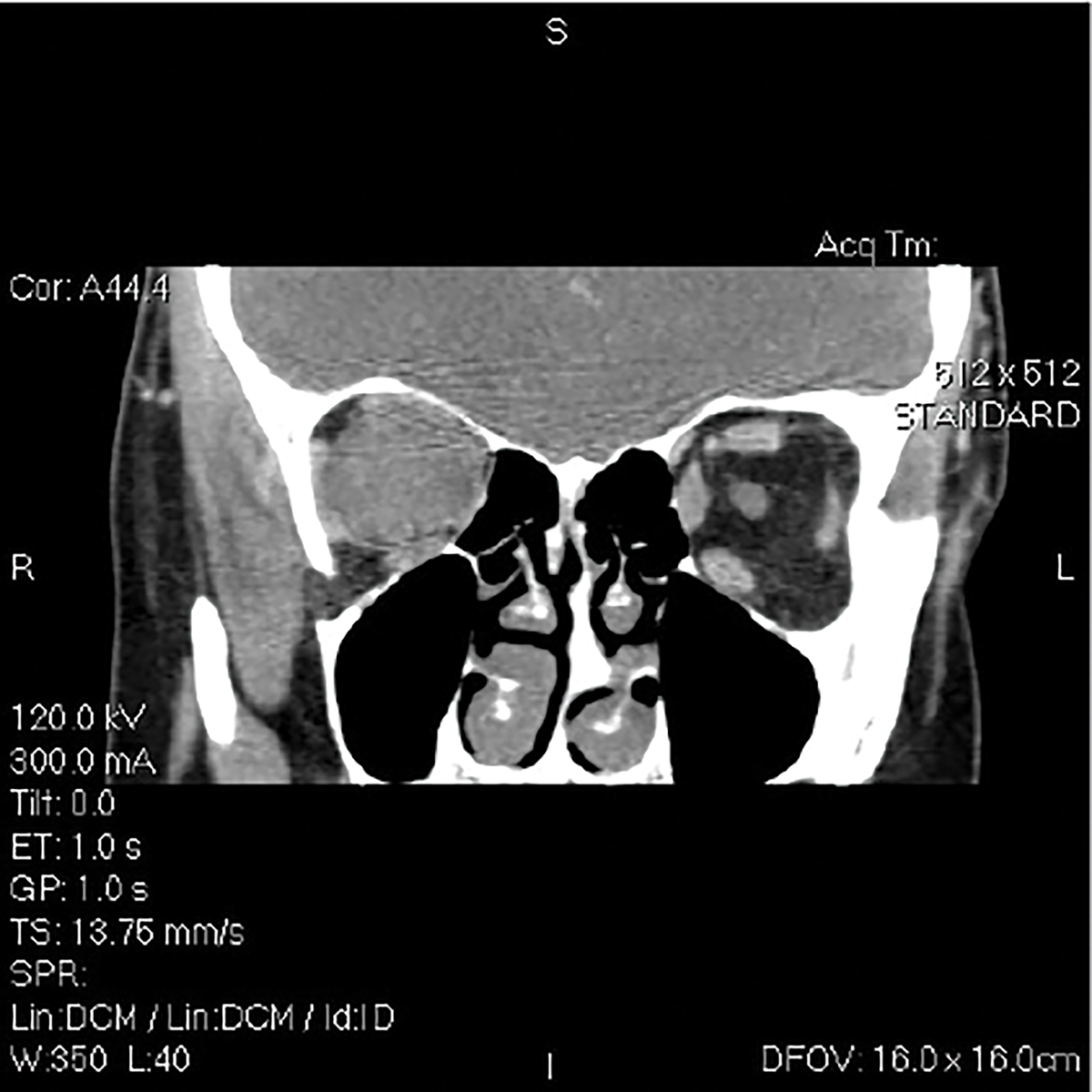

About a year later, the patient, now in her mid-20s, married and became pregnant. In the middle of her third trimester, her physician dad observed her right eye to be slightly hyperemic and slightly bulged. He was well aware that his daughter was very hyperopic, and high hyperopes with small globes don’t develop bulging eyes. Although he was very concerned, he waited until several weeks after the arrival of his first grandchild to have his daughter evaluated by an ophthalmic oncologist. Both MRIs and CTs revealed a mass nearly the size of her globe in the right orbit. Without a biopsy, the diagnosis arrived upon by the ophthalmic oncologists was an optic nerve glioma. The patient was treated with several sessions of tomotherapy—a form of irradiation—and her vision has remained stable.

|

|

Axial CT section at the same level as the previous image. Click image to enlarge. |

Malpractice Allegation

The patient sued the eyecare practitioner and neuro-ophthalmologist for failure to detect her orbital tumor years earlier. The orbital specialist opined that the long-term history of reduced vision in the right eye and persistence of an inferior altitudinal field defect in the right eye suggested that the orbital tumor was present some eight years earlier when she saw the neuro-ophthalmologist. After reviewing the neuro-ophthalmologist’s findings, the more current testing revealed that the tumor had progressed with subsequent expansion of the optic canal, now threatening the chiasm. Best-corrected VA after treatment in the OD was 20/80 to 20/100.

You Be the Judge

In light of the facts presented thus far, consider the following questions:

- Was the primary eye clinician justified to arrive at a diagnosis of amblyopia in the OD?

- Was the referral to a specialist in a different city justified when a repeatable field defect was documented?

- Should the neuro-ophthalmologist have obtained neuroimaging?

- Is it possible for the VA reduction in the OD to be due to four different causes?

- Is the primary eye clinician culpable of malpractice?

- Is the neuro-ophthalmologist culpable of malpractice?

- Is the patient partly responsible for the delayed diagnosis?

- Is the patient’s dad, a licensed physician, who treated his daughter, partly responsible?

|

|

Coronal CT section through the orbital mass OD (left) and the optic nerve OS (right). Click image to enlarge. |

Our Opinion

One of us (JS) was requested to review the case, concentrating on the care rendered by the primary eye clinician, an optometrist. After reviewing all the available information, I reached the conclusion that the diagnosis of amblyopia was justified, because of the hyperopic anisometropia. Moreover, the referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist met the standard of care when a repeatable field defect in the right eye was documented. The neuro-ophthalmologist also detected a small constant unilateral strabismus in the right eye, which is also recognized as a cause of monocular reduced vision, or amblyopia. Both clinicians detected hypoplastic discs, a smaller disc in the right eye than the left eye, and a hypoplastic disc is often the etiology of reduced VA and variable field loss.1 One of us (SB) examined two patients with hypoplastic discs, both of whom demonstrated repeatable inferior field defects in the eye with the hypoplastic disc.

One expert opined that the glioma was most likely present but dormant for years, and the pregnancy initiated the growth of the tumor. The plaintiff’s attorneys had difficulty finding experts to testify against the optometrist and even greater difficulty in finding a neuro-ophthalmologist to testify against one of the nation’s premier neuro-ophthalmologists.

The plaintiff’s attorneys produced pictures of the patient’s face over a decade that clearly documented subtle but increasing exophthalmos of the right eye. I agreed that this carefully selected group of images over a decade documented increasing exophthalmos on the right side only but noted that the patient, her childhood boyfriend and her dad (a treating physician) did not notice it. Remarkably, the plaintiff’s attorneys then resorted to claiming that images of a patient’s face should have been taken by the optometrist on each visit for over a decade. But of course, this is not the standard in ophthalmic care. This case was settled for a modest amount.

Takeaways

This is a remarkable case in that there are four possible etiologies for the VA reduction OD:

- Hyperopic anisometropia.

- Constant unilateral strabismus.

- Optic nerve hypoplasia.

- Orbital glioma.

| NOTE: This article is one of a series based on actual lawsuits in which the author served as an expert witness or rendered an expert opinion. These cases are factual, but some details have been altered to preserve confidentiality. The article represents the authors’ opinion of acceptable standards of care and do not give legal or medical advice. Laws, standards and the outcome of cases can vary from place to place. Others’ opinions may differ; we welcome yours. |

Dr. Sherman is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry and editor-in-chief of Retina Revealed at www.retinarevealed.com. During his 52 years at SUNY, Dr. Sherman has published about 750 various manuscripts. He has also served as an expert witness in 400 malpractice cases, approximately equally split between plaintiff and defendant. Dr. Sherman has received support for Retina Revealed from Carl Zeiss Meditec, MacuHealth and Konan.

Dr. Bass is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY College of Optometry and is an attending in the Retina Clinic of the University Eye Center. She has served as an expert witness in a significant number of malpractice cases, the majority in support of the defendant. She serves as a consultant for ProQR Therapeutics.

1. Sadun AA, Wang MY. Abnormalities of the optic disc. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 102. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2011:117-57. |