|

A 45-year-old male with his own construction business presented for a visit complaining of blurry vision when reading. He was examined and corrected to 20/20 with a pair of reading glasses. He had been followed in the practice for over 14 years and was status-post LASIK, although he still wore contact lenses for best correction. The patient did not want to be dilated so Optos photos were taken. The practitioner noted posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) in both eyes, but no other retinal abnormalities.

For the next year, the patient was followed for three visits related to contact lenses and dry eye secondary to the LASIK. At each visit the patient deferred dilation. Six months after his last follow-up, he presented with a different complaint. The practitioner wrote “patient started seeing a shadow in the left side of the right eye […] it is there when looking to the right, not as much looking straight or to the left.” The practitioner noted “no flashes, history of floaters.”

|

|

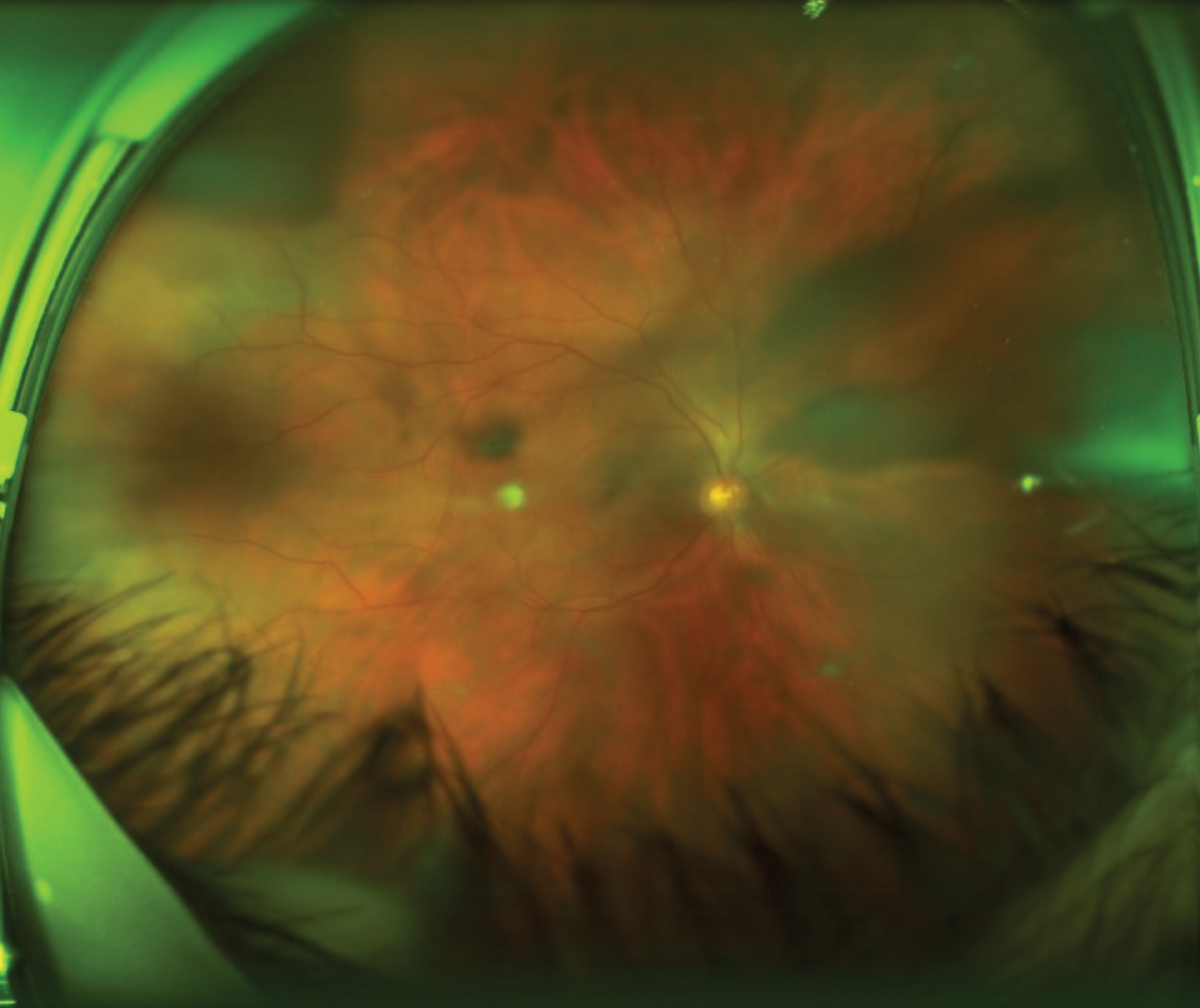

Fig.1. Optos photo of the right eye, with two cortical spokes nasally and a wide one superior temporal. Click image to enlarge. |

Testing

The practitioner noted uncorrected visual acuities of 20/40 in each eye but not corrected acuities. No anterior segment abnormalities were noted. Biomicroscopy was performed but the practitioner did not note the presence or absence of pigmented cells in the vitreous, the so-called “Schafer’s sign,” which can indicate the possible presence of a retinal tear. The patient was dilated with 1.0% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine. The dilated fundus examination was performed, and the practitioner noted “new and large vitreal strands OD.”

Because of the specificity of the patient’s new complaint about the shadow being more obvious when he looked to the right, the practitioner was more suspicious of a problem in the temporal retina of the right eye (nasal field). Several Optos photographs were taken using steering with emphasis on the temporal retina (Figure 1).

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with a shadow “due to new vitreal strands and a new PVD.” The practitioner wrote “reviewed retinal detachment, the signs and symptoms today…” No return appointment was scheduled.

|

|

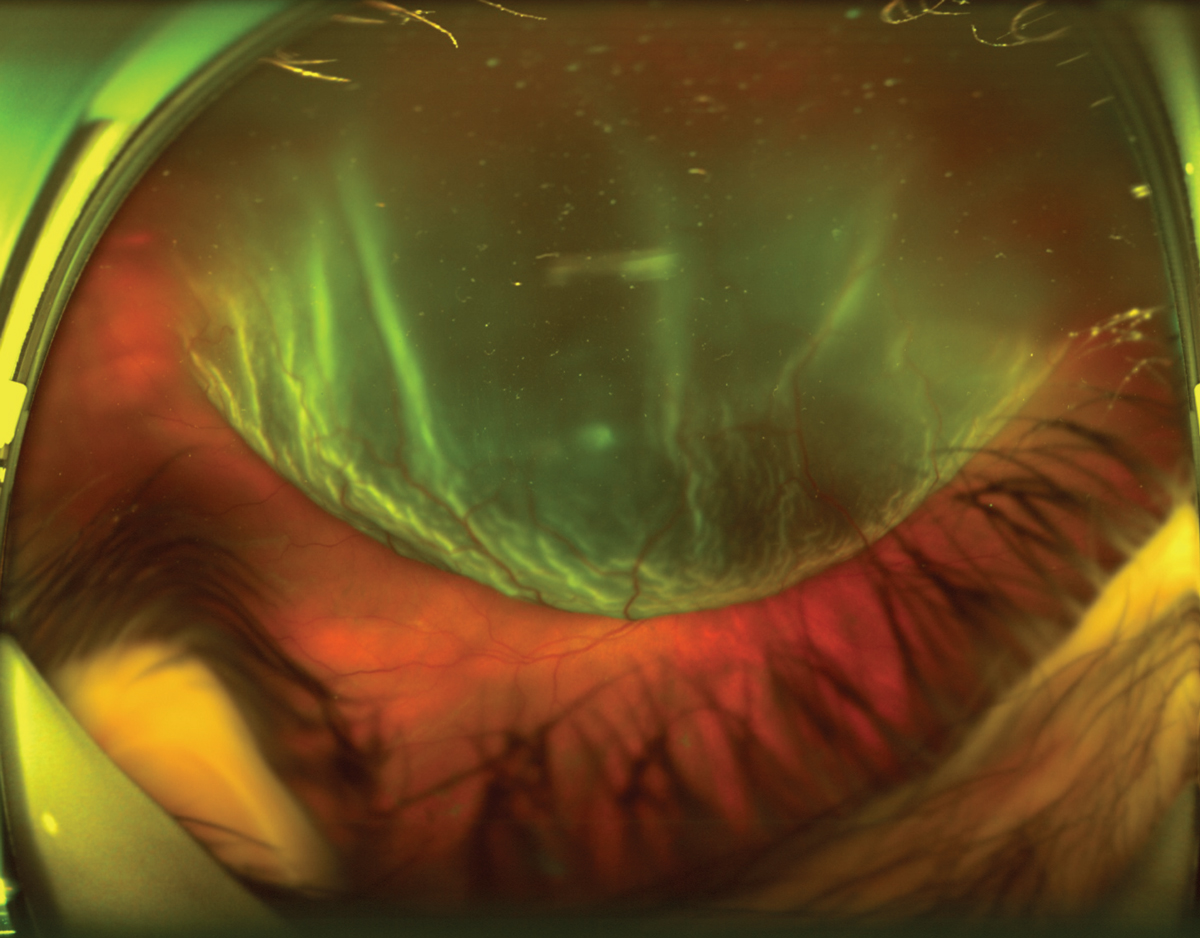

Fig. 2. The retinal specialist described a superior-temporal macula-off retinal detachment. Click image to enlarge. |

Follow-Up

The patient returned one month later with a complaint that he woke up with reduced vision in the right eye only that morning and that he had had flashes and floaters, which had started two days before. Visual acuity in the right eye was hand motion. Examination revealed a large retinal detachment (Figure 2). The patient was immediately referred to a retina specialist, who diagnosed a superior-temporal tear and a large bullous macula-off retinal detachment. The detachment was repaired one day later. One month later, the visual acuity had improved to 20/80, and the patient reported that the vision was still distorted. Two months later, the patient reported that images appeared “bent” in the center of vision in his right eye when performing daily tasks.

The patient was noted to have developed a 2+ nuclear and posterior subcapsular cataract (secondary to the vitrectomy performed during the retinal repair) and a new epiretinal membrane with macular edema. A membrane peel was recommended, as was cataract extraction.

Five months later, the best-corrected visual acuity remained 20/60 in the right eye. The patient initiated a malpractice lawsuit against the practitioner for failure to diagnose the retinal detachment when he initially complained of the shadow and for failure to refer him to a retina specialist for prompt treatment.

The patient claimed that the failure to detect the detachment on the day he was experiencing the shadow delayed treatment, resulting in a macula-off retinal detachment and two surgeries, which resulted in irreversible reduction of vision in the right eye with distortions in his vision that he claimed made it difficult to perform his construction work.

You Be the Judge

Was there a retinal detachment when the patient initially complained of a shadow? The practitioner did not see a detachment but took photos. Do you see a retinal detachment in Figure 1?

If the practitioner did not see a detachment, should the patient have been referred to a retina specialist for supplementary testing procedures, such as scleral depression, three-mirror contact lens examination and/or B-scan ultrasonography? Should the practitioner have made a follow-up appointment after the initial examination?

Our Opinion

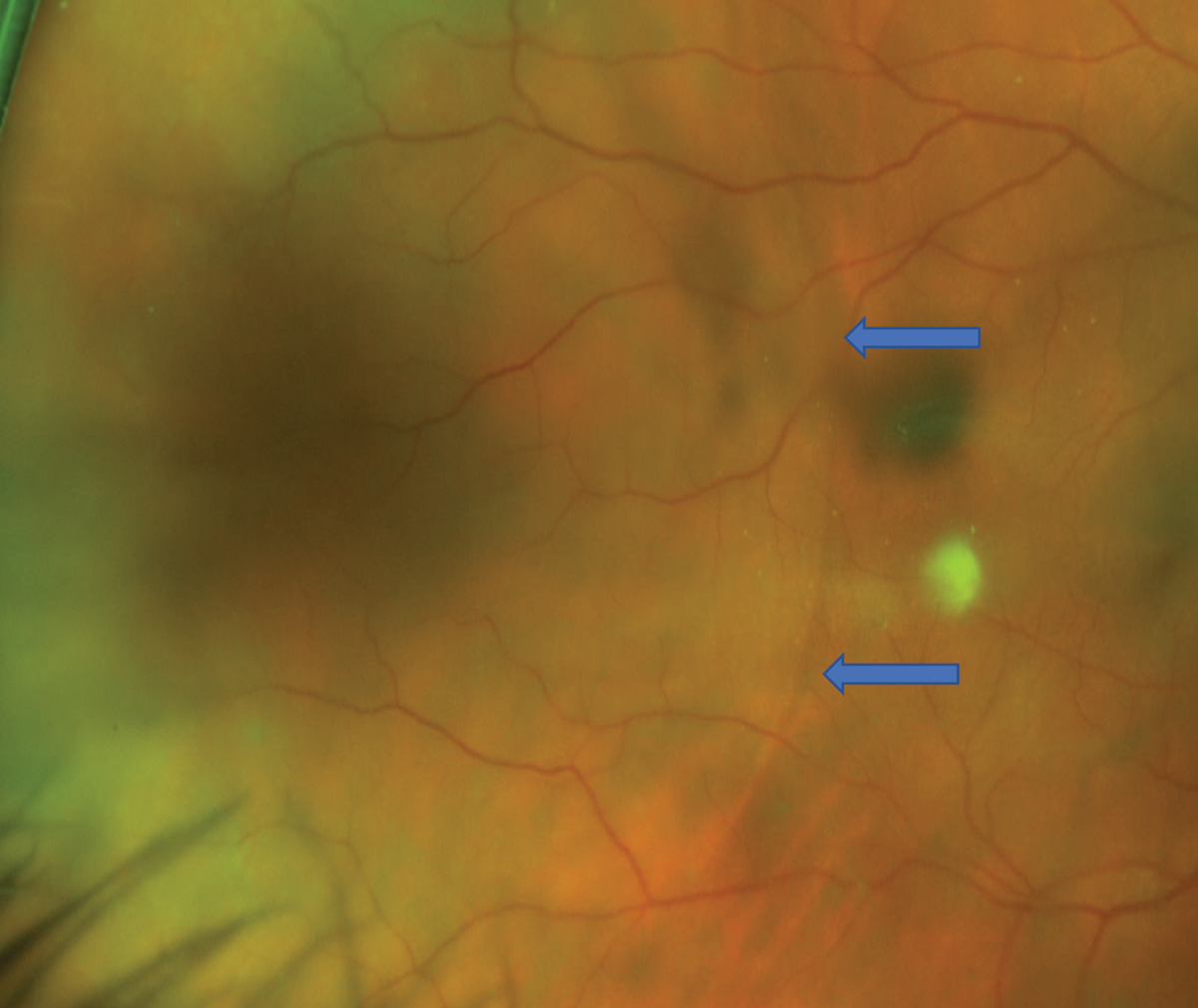

This case is unusual because, unbeknownst to both of us, we were each asked to opine for opposite sides. One of us (JS) opined that the practitioner performed a standard-of-care examination and that, based on the photos, a detachment was not evident. In addition, the superior-temporal detachment that ultimately occurred was not evident in the earlier photographs. The other one of us (SB) opined that, on careful examination, a possible shallow retinal detachment was visible in the temporal retina of the right eye in the photographs (Figure 3).

Although the average practitioner may not have appreciated the possible shallow retinal detachment on the photograph, standard of care would have dictated that the practitioner refer the patient for supplemental testing and examination, especially considering the patient’s chief complaint of a shadow that was more visible when he looked to the right. He did not complain of a floater or say that the shadow moved across his vision.

Litigation Outcome

The case was settled for an undisclosed amount.

|

|

Fig. 3. Magnified view of the temporal retina OD one month prior to large retinal detachment. It reveals a circular border, possibly denoting a shallow retinal detachment (blue arrows). Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

In the “Clinical Practice Guidelines of the American Optometric Association for the Care of the Patient with Retinal Detachment and Peripheral Vitreoretinal Disease,” it is stated that supplemental testing may be indicated to rule out a tear and/or detachment.1 The practitioner did not perform any supplemental testing, and the average practitioner under like circumstances would likely not have performed supplemental procedures since many ODs are not able to perform a three-mirror contact lens exam and scleral depression proficiently and most do not have access to B-scan ultrasonography.

The practitioner in their deposition admitted to referring retina patients occasionally to a retina specialist, hence this patient could have been referred for supplemental testing. History is also an important consideration. In a recent retrospective cohort study of 8,305 patients with acute-onset PVD, results revealed that variables that are associated with greater risk of retinal tear and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment following acute-onset PVD included blurred vision, male sex, age younger than 60, prior keratorefractive surgery and prior cataract surgery.2

The patient in this case had prior LASIK and was a 45-year-old male. Symptoms of sudden onset of floaters, flashes and/or a field defect (or shadow) in the periphery that does not move should make the practitioner more suspicious of retinal detachment. In this case, the patient presented with the complaint of a shadow that appeared more obvious in certain fields of gaze and did not move.

The important lesson to be learned here is that any patient complaining of a shadow that is different from a floater should be referred for additional testing to rule out a tear or retinal detachment. Widefield photography is not a substitute for a thorough dilated fundus examination, and it is unfortunate this patient deferred dilation for a number of visits. Widefield photography is an adjunctive procedure that can indicate the presence of a tear and/or retinal detachment.

In this case, the dilated fundus examination performed by the practitioner did not reveal a tear or a detachment, but the photos they took, one of us (SB) believes, tell a different story.

In contrast, JS argued in his deposition that “a like practitioner under like circumstances” would not have noticed the very subtle curvilinear line in the Optos image that may not be an RD but rather a retinoschisis not requiring treatment (Figure 3). Furthermore, the detachment was in the far superotemporal quadrant a full month later and arguably had nothing to do with the curvilinear line in the posterior pole, which may or may not be a shallow RD. Even if the patient were referred, the superior-temporal tear that resulted in the bullous RD may not have been present a month earlier.

SB argued that a tear was likely evident at the initial visit, causing the shallow retinal detachment, and that a second, more superior tear could have developed later. If the patient were referred for supplemental testing, such as B-scan ultrasonography, a shallow retinal detachment could have been differentiated from a retinoschisis. JS further argued that there is no proof that the curvilinear line was a shallow RD, and, in the US, there is only one retina specialist per 100,000 population and referrals should be reserved for patients who are believed to require advanced intervention and not for every floater, flash or shadow. SB opined that the practitioner, in their deposition, claimed that a retina specialist was available and patients were referred all the time when needed, but the practitioner did not believe it was needed.

Both of us agreed that the shallow possible retinal detachment would likely not have been appreciated by the average practitioner, but we differ on the follow-up and the need for a referral.

The bottom line in this case is that the patient suffered a macula-off retinal detachment one month later in the same eye that might have been prevented had the practitioner referred the patient to a retina specialist sooner rather than later even if the practitioner did not detect a detachment.

But, you be the judge: did the clinician meet the standard of care practiced by “like practitioners under like circumstances?” We welcome your opinion as well.

| NOTE: This article is one of a series based on actual lawsuits in which the author served as an expert witness or rendered an expert opinion. These cases are factual, but some details have been altered to preserve confidentiality. The article represents the authors’ opinion of acceptable standards of care and do not give legal or medical advice. Laws, standards and the outcome of cases can vary from place to place. Others’ opinions may differ; we welcome yours. |

Dr. Sherman is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry and editor-in-chief of Retina Revealed at www.retinarevealed.com. During his 52 years at SUNY, Dr. Sherman has published about 750 various manuscripts. He has also served as an expert witness in 400 malpractice cases, approximately equally split between plaintiff and defendant. Dr. Sherman has received support for Retina Revealed from Carl Zeiss Meditec, MacuHealth and Konan.

Dr. Bass is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY College of Optometry and is an attending in the Retina Clinic of the University Eye Center. She has served as an expert witness in a significant number of malpractice cases, the majority in support of the defendant. She serves as a consultant for ProQR Therapeutics.

1. Optometric clinical practice guideline: care of the patient with retinal detachment and peripheral vitreoretinal disease. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org/aoa/documents/practice%20management/clinical%20guidelines/consensusbased%20guidelines/care%20of%20patient%20with%20retinal%20detachment%20and%20peripheral%20vitreotretinal%20disease.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2023. 2. Seider MI, Conell C, Melles RB. Complications of acute posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(1):67-72. |