|

Nearly two decades ago, a 35-year-old, high-strung, type A personality male was referred by an OD to a highly respected retina specialist because of reduced vision in his right eye for about one month’s duration. The patient reported no other symptoms or significant health history. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/50 OD and 20/20 OS. The external exam was normal, both pupils reacted to light and no Marcus Gunn pupil was observed.

The dilated fundus examination revealed subtle fluid in the macula and trace pigmentary changes at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the right eye only. The retinologist attempted to perform a fundus examination with a three-mirror lens, but the high-strung patient could not tolerate the procedure and the contact lens was dislodged several times—twice on the floor. Fluorescein angiography was performed, which revealed some ill-defined leakage in the posterior pole in the right eye only. The optic nerve head as well as the mid and far peripheral retina were judged as normal. The fellow left eye was completely normal.

The retina specialist diagnosed somewhat atypical central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) in this difficult to examine male patient. Note that two decades ago, OCT was in its clinical infancy and not readily available. B-scan ultrasound was available but not performed during the first several visits.

The patient returned as instructed five times over the next two years and was evaluated alternately by one of three optometrists in the practice. The condition remained essentially unchanged in both eyes. The patient missed several scheduled exams but on the last visit to the practice, the OD noted that the optic disc appeared slightly blurred in the right eye but normal in the left. A comparison to previous fundus photos suggested that the slightly blurred disc in the right eye was a new finding. The clinician reasoned that since the optic nerve head is never involved in CSCR, a different etiology must be considered.

B-scan ultrasonography was then performed for the first time, and although it did not reveal any retinal elevation, it appeared to reveal a thickened choroid extending to the optic nerve in the right eye, suggestive of an enlarging mass. Proptosis of the right globe was never observed.

The patient was immediately referred to an ophthalmic oncologist, who fully evaluated the patient including multiple scans of the globes, orbits and cranium. A somewhat unusual choroidal malignant melanoma was diagnosed, which appeared to be growing backwards into the orbit and was wrapped around the optic nerve. No typical mushroom-shaped lesion extending into the vitreal cavity was revealed by B-scan or MRI.

|

|

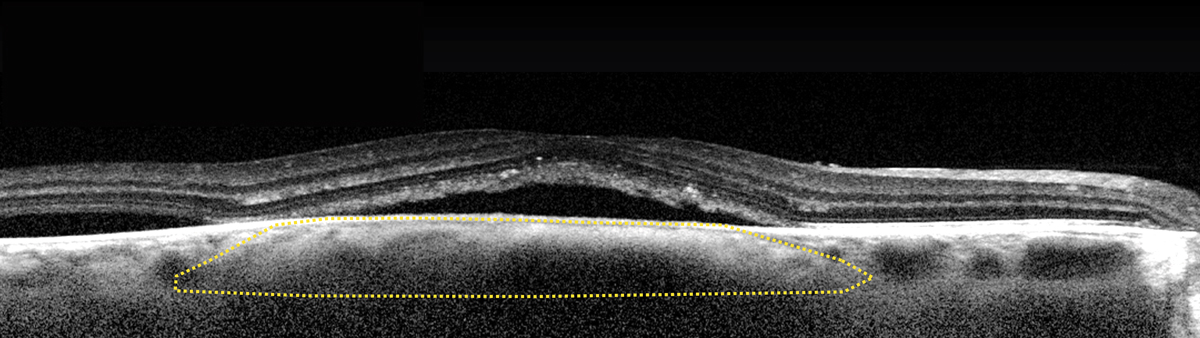

Subfoveal choroidal melanoma with subretinal fluid that could be misread as CSCR. Photo: Carol Shields, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

Outcome

Based upon the size of the lesion and absence of evidence of metastasis on an extensive systemic work-up, the ophthalmic oncologist recommended enucleation. The patient agreed, and the mass was later confirmed histopathologically to be a mixed cell type malignant melanoma.

Five years after uneventful ocular and systemic follow-ups, most patients with cancer are classified as cured. However, in this case, worsening liver enzymes at five years and a repeat liver scan revealed for the first time multiple, suspicious lesions, essentially confirming metastasis.

The patient died in the sixth year following enucleation. The family apparently initiated a lawsuit for failure to diagnose the choroidal melanoma two years earlier, but the case was reported to be dropped.

You Be the Judge

Was the retinologist culpable of malpractice for arriving at a diagnosis of CSCR that was not supported by the clinical findings?

Were the ODs who performed the follow-up exams culpable?

Were so-called flat choroidal melanomas well appreciated at the time the care was rendered?

Has technology and knowledge evolved recently that alters the standard of care in similar cases?

|

|

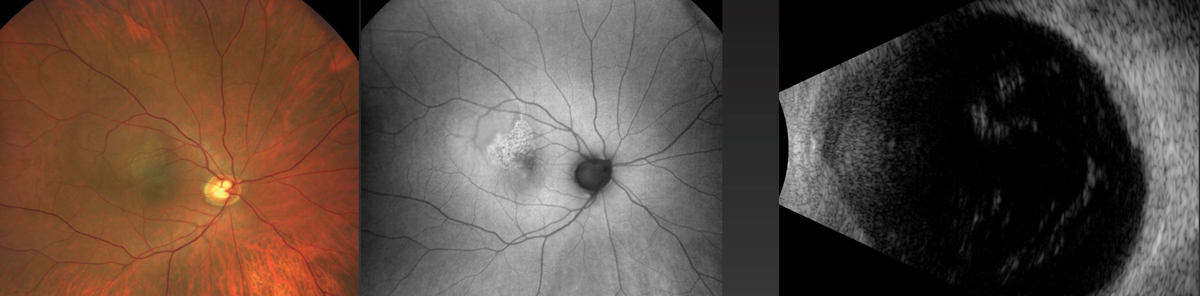

A comparison of fundus imaging (left), autofluorescence (middle) and ultrasound (right) for the same case as the previous image. The ultrasound B-scan appears to be the most sensitive to detect this relatively flat melanoma. Photo: Carol Shields, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

Our Opinion

In select cases such as this, clinicians can easily be misled and arrive at the most common diagnosis linking the symptoms, patient characteristics and clinical findings together and failing to consider a far rarer—but potentially deadly—diagnosis.

CSCR in a type A behavior, middle-aged male whose exam reveals macula fluid and RPE changes is the diagnosis that most clinicians would most likely arrive upon, at least several decades ago. Considering the guideline—“like practitioner under like circumstances”—we find the doctors involved in this tragic case not culpable of malpractice.

One could argue that clinicians should consider “worst… first” in diagnosis in order to avoid outcomes such as this. The opposing argument is that we cannot obtain MRIs and other expensive, and sometimes invasive, tests indiscriminately because of the limited health care resources available.

Most clinicians think of choroidal malignant melanoma as an elevated mass and not a flat lesion with minimal or no obvious elevation. Hopefully, our comments below will expand the clinician’s knowledge about these rare tumors.

Comments

The selection of this case was initiated by a recent presentation by Carol Shields, MD, at the Macula Society 46th Annual Meeting in Miami Beach in mid-February that one of us attended (JS). Dr. Shields presented a talk, “Choroidal Melanoma Masquerading as Central Serous Chorioretinopathy.” Her group at the Ocular Oncology Service at Wills Eye Hospital performed a retrospective case series review of all patients with choroidal melanoma over the past two decades initially misdiagnosed as CSCR elsewhere.

Of the 22 patients identified, 16 were male and the mean age was 48. The mean interval between initial CSCR diagnosis and suspicion of choroidal melanoma was 50 months. At tumor diagnosis, the tumor was submacular in 16 of the 22 patients. On a mean six-year follow-up, one patient of the 22 died.

The conclusion from Dr. Shields’s study was that patients with presumed CSCR, especially if chronic, should be evaluated for a possible thin underlying choroidal melanoma with a dilated fundus exam and multimodal imaging.1 Dr. Shields noted that features enabling differentiation of choroidal melanoma from CSCR included choroidal thickness asymmetry, ipsilateral choroidal surface irregularity, loss of choroidal vascular detail on OCT and lack of autofluorescence abnormalities in the fellow eye.1 CSCR is often bilateral but asymmetric, whereas choroidal melanoma is virtually never bilateral.

Note that the patient we are reporting in this column was evaluated prior to the clinical availability of OCT and fundus autofluorescence and prior to the Shields study, emphasizing the need to consider a thin underlying choroidal melanoma in a patient with chronic, unilateral CSCR.

Hence, the standard of care has evolved somewhat over the past two decades because technology and knowledge has evolved. Although our opinion is that no culpability exists in this case, a similar case today may result, in our opinion, in culpability. Far more important, a similar case today could perhaps result in a timelier diagnosis and preservation of a life.

We applaud Carol Shields, MD, and Jerry Shields, MD, for their decades-long contributions in ophthalmic oncology.

| NOTE: This article is one of a series based on actual lawsuits in which the author served as an expert witness or rendered an expert opinion. These cases are factual, but some details have been altered to preserve confidentiality. The article represents the authors’ opinion of acceptable standards of care and do not give legal or medical advice. Laws, standards and the outcome of cases can vary from place to place. Others’ opinions may differ; we welcome yours. |

Dr. Sherman is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry and editor-in-chief of Retina Revealed at www.retinarevealed.com. During his 52 years at SUNY, Dr. Sherman has published about 750 various manuscripts. He has also served as an expert witness in 400 malpractice cases, approximately equally split between plaintiff and defendant. Dr. Sherman has received support for Retina Revealed from Carl Zeiss Meditec, MacuHealth and Konan.

Dr. Bass also holds the position of Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry. She is a Diplomate of the American Board of Optometry. She is an attending in the Retina Clinic of the University Eye Center and currently serves as the residency supervisor for the Residency in Ocular Disease at SUNY. She has no financial disclosures.

1. Negretti GS, Kalafatis NE, Shields JA, Shields CL. Choroidal melanoma masquerading as central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2023;7(2):171-7. |