Bright Ideas for Better ExamsThe February 2023 issue of Review of Optometry is our annual diagnostic skills and techniques issue. In each article, eyecare experts offer practical tips and advice to help you brush up on exam techniques that you can put to use everyday in your office. Check out the other articles featured in this issue:

|

Part 1 is below. Part 2 can be found here.

With an aging population and the number of patients needing ophthalmic care increasing, many individuals will need eye care that involves more than just routine wellness evaluations. Fitting with this need, optometrists occupy a strategic healthcare position, able to coordinate care with other specialty providers. Ultimately, this offers the patient an enhanced and more complete level of care, addressing any underlying problems they present with at the office.

The Institute of Medicine defines primary care as the following: the provision of integrated, accessible healthcare services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal healthcare needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients and practicing in the context of family and community.1

The role of the optometrist in providing care for the eye and visual system is well established and, many times, these are affected by systemic diseases that may or may not already be diagnosed. In any event, we are all seeing patients who bring with them problems affecting the visual system. It is incumbent upon our profession to facilitate and coordinate care when the patient’s problem requires the aid of expertise of other healthcare providers.

|

|

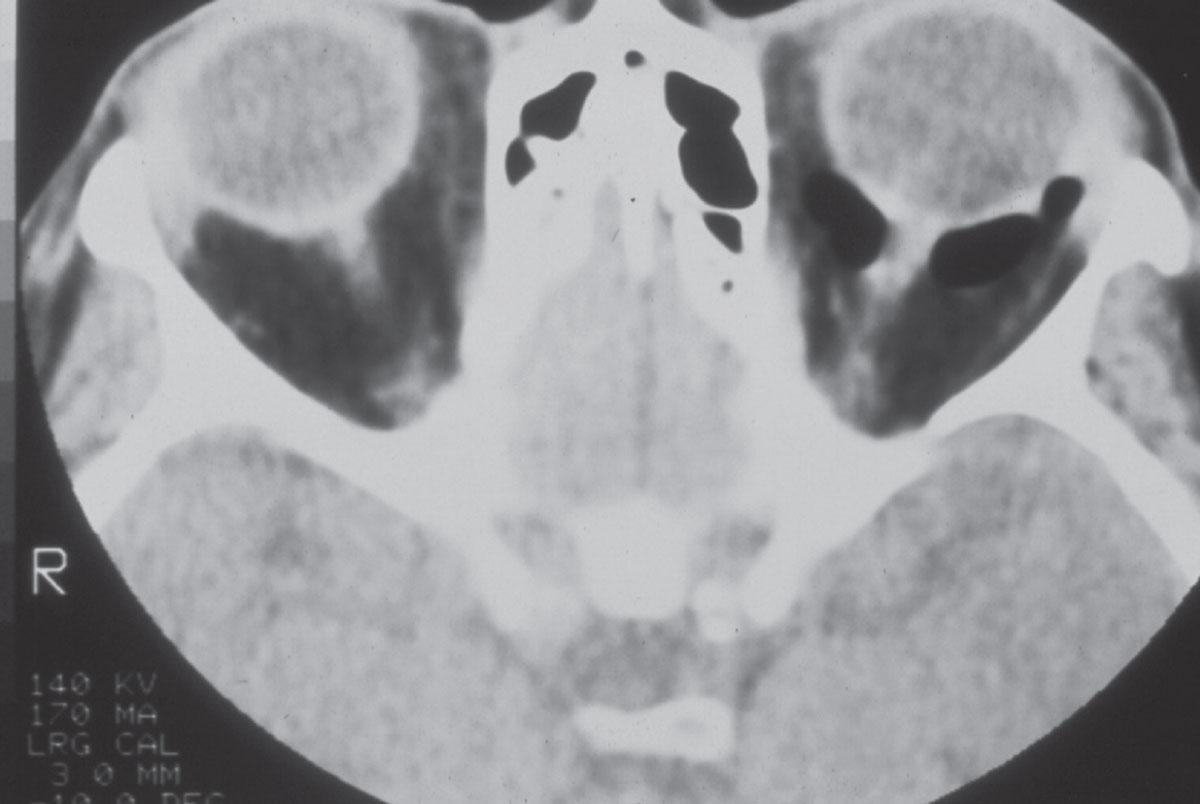

A CT scan of a patient with a left orbital floor fracture. While the fracture is not seen in this particular scan image, the air seen behind the left eye surrounding the optic nerve is consistent with communication between the orbit and the maxillary sinus. Click image to enlarge. |

In many instances, laboratory and imaging studies are an integral part of the work-up for these patients, and there are several ways in which optometrists can play a role in coordinating care for these individuals. In this two-part article, we will first (this month) go through the practical challenges of adding these diagnostic capabilities and then (in part two) work through several specific clinical examples of how they can improve the care you provide.

Why Order Lab and Imaging Studies?

Frankly, there are many potential answers to this question, all of which are predicated upon the specific disease or clinical finding in question. Lab and imaging studies are important in the initial phases of examining a patient with suspicious findings to monitor said condition once a diagnosis has been made or proffered and continuing to follow these patients once firm diagnoses are solidified. For example, a patient who presents with unilateral proptosis (whether it is obvious or subtle) with extraocular movement abnormalities has a high suspicion of an orbital etiology. That pathology may be related to thyroid abnormalities, in which case both lab and imaging studies are helpful in developing a diagnosis. Better put, these studies are important for determining differential diagnoses or confirming a suspected diagnosis.

Once a diagnosis is made, further studies are often required to adequately monitor the response to treatment of the condition. In cases of diabetes, for example, HbA1c readings do just this; they allow the provider a good glimpse at how well their patient’s diabetes is being controlled. Note that patients with acute afferent visual field abnormalities are in need of neuroimaging. This is not only to identify the location of the underlying problem but also to shed light onto the cause of this problem. Is this an acute infarct, is it the result of a demyelinating process or perhaps a space-occupying lesion?

|

|

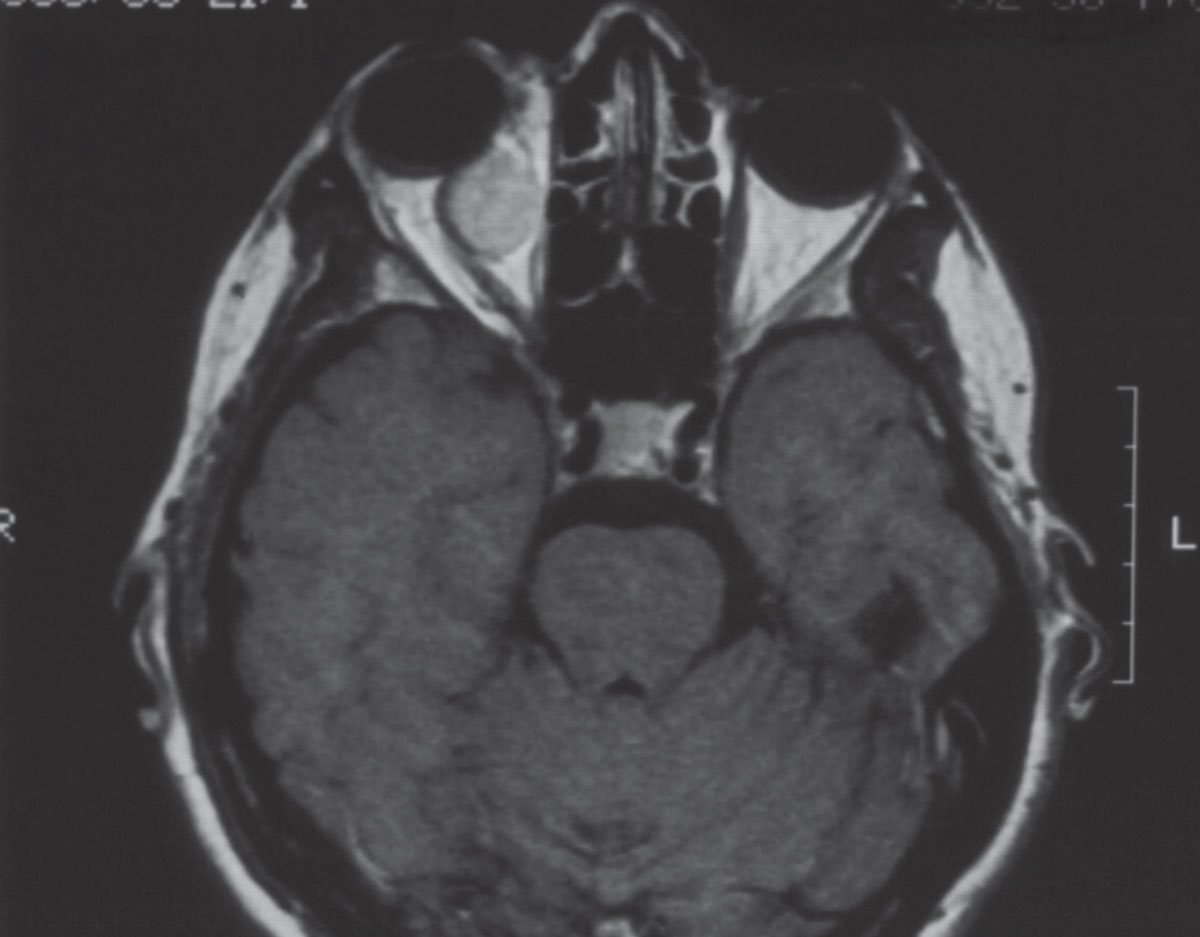

An axial MRI image demonstrating the presence of an enhancing mass in the right orbit. Note also the presence of proptosis seen on the right side as compared with the left. Click image to enlarge. |

The scenarios are endless and those who have been in practice long enough have seen their fair share of patients with problems who require lab and imaging studies. In general, lab studies are directed toward identifying abnormal physiologic processes while imaging studies are directed toward identifying structural abnormalities. Not surprisingly, many disease entities demonstrate both abnormal physiologic processes and structures, prompting the need for both lab and imaging studies.

Who Should Order the Studies?

This is a more complex issue than it may initially seem and depends on several factors. There are two general routes an OD may take. The first would be that lab and imaging studies can be obtained when an optometrist sees a patient who needs further investigation and the patient can be referred out to another provider best-suited to evaluate the suspected condition. The second option is when the optometrist can orchestrate the initial lab and/or imaging studies. In both cases, subspecialty care will often be involved; the practical difference is at what point they are brought into the case. That will vary depending on the condition, the optometrist’s comfort level with managing these situations and their relationship with the general medical community. Both options are correct. Ultimately, the patient’s primary care provider (PCP) will be made aware of the situation once the patient is on the right track. But, in certain cases and with certain disease processes, such as acute neuro-ophthalmic situations, having the PCP drive the initial work-up and evaluation process may result in delayed care.

As with general medicine, where there may be several areas of interest and expertise of the provider, the same holds true for optometry. Some primary care practitioners see a generally younger and healthier population, whereas others see older patients who have several ongoing disease processes. In the same way, some optometrists may specialize in contact lenses, pediatrics or binocular vision, while others are more diversified in their emphasis of care. Some of us specialize in glaucoma and neuro-ophthalmic disorders while others are strictly anterior segment specialists.

It’s not feasible to expect a contact lens practitioner to be fluent in the nuances of neuro-ophthalmic disorders, just as it is not feasible to expect a posterior segment specialist to be cognizant of the nuances of specialty scleral lens designs. But what is a reasonable expectation is for every optometrist to be cognizant of a disease process occurring in an area of the eye and visual system outside their area of expertise.

Therefore, my suggestion would be that for those providers encountering a condition outside of the visual system they are not proficient in, referral to a fellow provider—OD, MD or other—is appropriate earlier on in this process. However, for those providers who practice in their area of expertise and encounter patients with problems in said areas of the visual system, then there is no harm in initiating the appropriate lab and imaging study orders themselves. That is, so long as two important things follow the ordering: the first is to understand specifically what to order and how to interpret those findings. The second is to act upon those findings in an appropriate manner.

Oftentimes in lab study ordering, the results are presented in a fashion where base values are obtained (for example in a CBC), but the interpretation of that information is left to the ordering physician. For most ordered neuroimaging, on the other hand, there is usually a radiology report sent to the ordering physician with the clinical findings outlined. In short, the OD has the benefit of receiving the radiologist’s interpretation of the scans along with the scans themselves. While the radiology report summarizes the findings seen in the images, the OD does need to be able to interpret the clinical implications of the report. Whereas with reviewing lab results, the OD does need to possess the ability to interpret the specific findings and coordinate that with the clinical case presentation, since there is no interpretation report that comes with lab studies other than cursory comments from the lab regarding a specific index or test result.

Once the results of the test(s) are interpreted, it is then important that the OD knows what needs to be done with that information. Take the case of a patient who presents asymptomatically with a retrochiasmal visual field defect that is seen during an eyecare visit. The provider knows there is a structural defect resulting in the field loss. What the provider does not know is when that event occurred. It may have happened months or years ago, or it may have been recent. Nor does the provider know what caused the event.

|

|

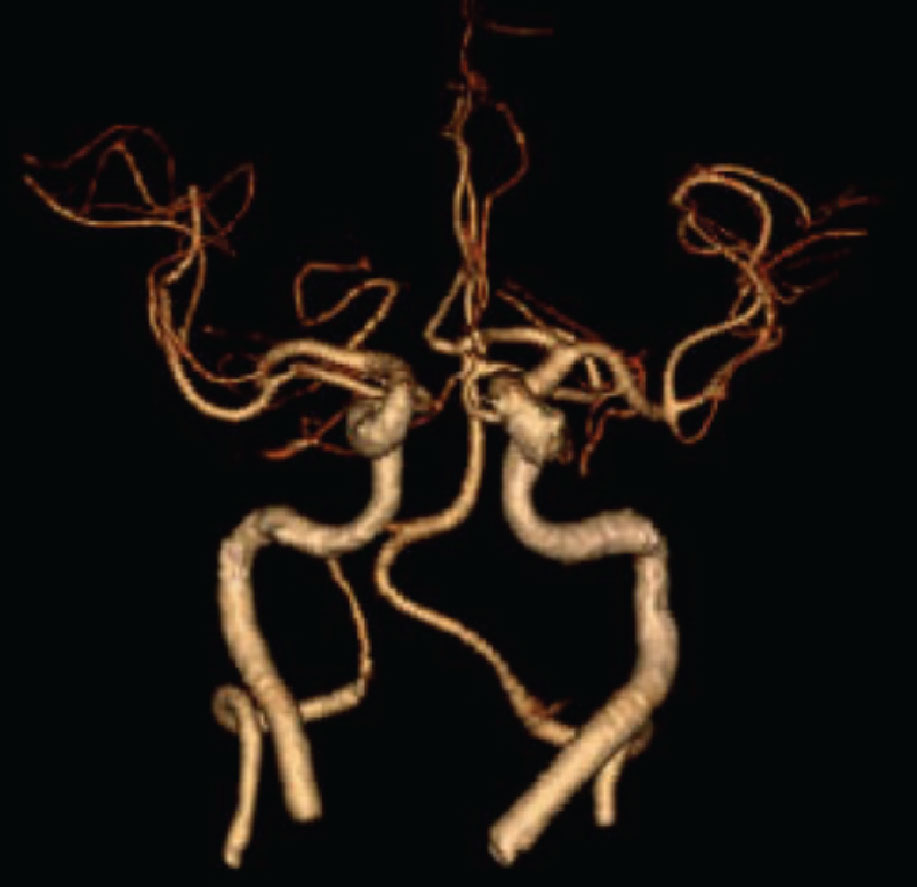

A CT angiogram of the neck and intracerebral arterial vasculature. In this antero-posterior view, one can clearly visualize the internal carotid arteries, the vertebral arteries, a portion of the circle of Willis and the anterior and middle cerebral arteries on both the right and left sides. Click image to enlarge. |

Neuroimaging helps very much with determining the chronicity of an ictus. Does the patient need to be sent to a stroke unit immediately or are the MRI findings consistent with longstanding cerebral ischemia? Just because the clinician is seeing a new finding for the first time does not mean that the finding is of new onset. In other words, the currently asymptomatic patient may have had a chronic ischemic event months ago that caused the field defect, but if the MRI is not showing evidence of acute ischemia, an immediate referral to a stroke center is not necessary. What is appropriate in this situation is a referral to the appropriate healthcare provider to mitigate the risk of future events.

Being able to establish a management plan for patients after ordering lab or imaging studies and after the clinical evaluation that precipitated the testing is an important part in their care. It is the same with our glaucoma patients—once all the data is in, only then can you create a targeted, focused management plan.

Options for Ordering Labs and Imaging

Once the decision has been made that lab and/or imaging studies are warranted, what options do ODs have for obtaining these tests, if they choose to do the ordering? This answer depends on your location, mode of practice and what you are ordering, to a large degree.

Lab test ordering. Most ODs, independent of their practice setting, do not draw blood in their office. For those ODs in multidisciplinary and hospital settings, ordering lab testing is often straightforward: orders are sent to the in-house lab for the specific tests needed. For most other ODs in practices not part of a multidisciplinary setting, commercial labs are best-suited to obtain the necessary testing. There are many nationwide commercial laboratories where this can be done, such as Solstice Labs, LabCorp and Roche Diagnostics, to name a few. Do keep in mind that many of these labs supply offices with the items necessary to draw blood in the clinic. These specimens are ultimately transported to the lab facility for analysis. While that may not work for you, these same commercial labs do possess the capacity to have your patients instead go to their facility. From there, patients can have their blood drawn and analyzed, saving you the need to collect the specimens in your office.

Setting up an account with these facilities is straightforward. Simply contact your local lab and say that you have the occasional need for lab studies and that you’d like to set up an account with the company. When a patient needs labs, you can send them directly to the lab along with your orders. The lab will then send you back the results for you to interpret and act upon.

There is another nuance to lab studies that must be considered: should you send the patient to their PCP for the lab work? I think that much depends on your relationship with the PCP. If you already have a great relationship with the patient’s PCP and they value your contribution to the health care of the patient, then certainly, have the patient go to their PCP’s office for the bloodwork. They don’t necessarily need to see their PCP at that point in the care of the patient, but the lab results will be automatically incorporated into the patient’s medical record there with the results forwarded to you. Coordination of care with the PCP for that patient, if needed, can then easily take place.

But what if the patient’s PCP is someone who does not value your opinion, or consistently refers mutual patients that you send to them to another provider, usually an ophthalmologist? Of course, the first question to ask is whether or not you believe that provider offers the patient the best possible care when they consistently refer your mutual patient to ophthalmological practice. It may not be in the patient’s best overall interest, driving up healthcare costs. While the PCP will ultimately need to know the results of such bloodwork, consider sending this patient to a commercial lab for the specific tests you require. Then, after reviewing the results, inform the PCP of your diagnosis and plan.

This scenario plays out often enough when ODs send patients to their PCP because of retinal hemorrhages. There are many causes of this condition, some of which carry significant risk, while others may be innocuously due to a Valsalva maneuver in the presence of a patient who is also anticoagulated. You, as the primary provider for the patient’s eye and visual system, know what your differentials are and, consequently, your level of concern. In contrast, the PCP usually does not know what the differentials are (in reference to the types and locations of retinal hemorrhages seen during funduscopy) and oftentimes reverts to thinking that since the patient’s eye is bleeding, they need to be seen by a retina specialist ASAP. They also may not completely understand an OD’s competence is in this area and may not know the finer nuances of retinal hemorrhage etiologies. To avoid this scenario, it’s reasonable to order the appropriate bloodwork and subsequently inform the PCP of the findings and the plan you have generated for the patient. You can then inform them of when you plan to see the patient back, as one would in the case of an isolated Valsalva hemorrhage.

|

|

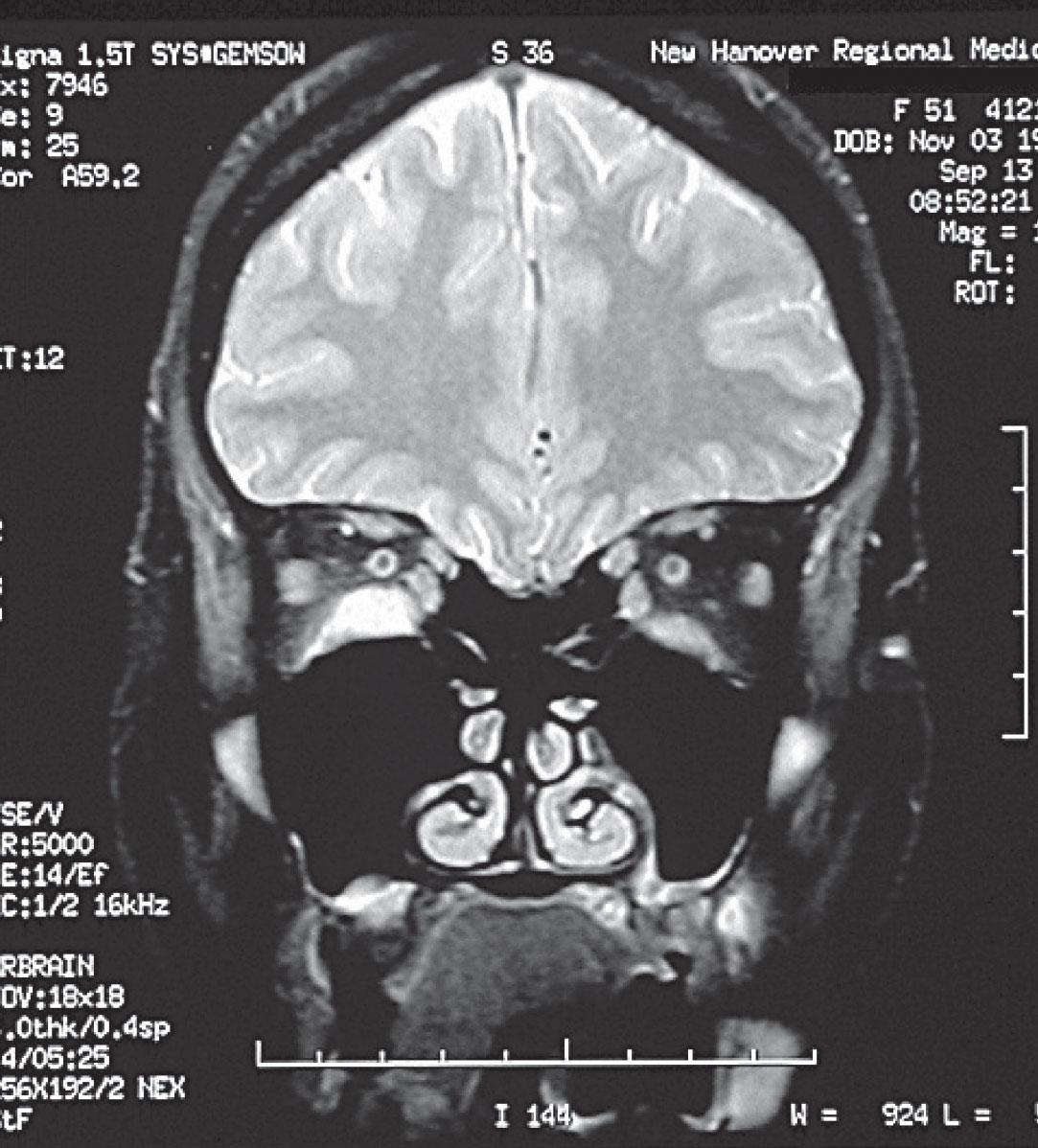

A coronal MRI of the orbits in a patient with Graves’ disease, demonstrating enlargement of the inferior recti muscles, right > left. Click image to enlarge. |

Image ordering. Through the same means, vascular ultrasonography, CTs and MRs can be obtained by the hospital or multidisciplinary setting in which you work. Other times, you can order the necessary imaging directly through a radiology-owned imaging center. Some hospitals require you to have hospital privileges to order the images, while others do not. In many cases, though, this will not necessarily be the barrier to obtaining scans. Instead, an issue may arise because of the need for prior approvals before imaging is obtained. Doppler imaging for carotid studies can be ordered from a vascular or cardiac surgeon’s office directly, which is a great way to develop relationships with these specialty providers.

When ordering CT and MR imaging (included with these are specific subsets of CT and MR images, including CTA, MRA, MRV, etc.), it is imperative that you convey to the radiologist exactly what your tentative and/or differential diagnoses are, as well as to include any relevant clinical findings. By relaying these specifics, the radiologist can then use their judgment as to what particular image techniques should be used during image acquisition. Doing so focuses their attention on the distinct problem areas that can facilitate a relevant interpretation of the imaging.

You don’t necessarily need to specify the thickness of the slices of the CT, for example, nor whether to incorporate apparent diffusion coefficient mapping or diffusion-weighted imaging into the MRI protocol, since that is the job of the radiologist. However, you do need to give the radiologist precise information to focus on. For example, you might call attention to the pituitary region, visual cortex or the midbrain. Without this provided to the radiologist, there is a higher likelihood that the interpretation will not be as specific as needed for a firm diagnosis. Communication is key in ordering imaging, particularly for neuroimaging.

This type of order may sometimes be needed on an emergent basis, whereas other times is only needed on an urgent basis. Your clinical decision-making dictates how urgent or emergent the imaging is needed on a situational basis. When following up long after a patient with a history of, for example, pituitary adenoma and who underwent surgery, these scans are often scheduled on a non-urgent basis.

Availability to obtain scans in a timely fashion can sometimes be challenging aside from the issue of prior authorization. In many areas, CT scanning is generally more available on short notice than are MR scans; the difficulty lies in that CT scanning is not appropriate for many cases of neuroimaging.

|

|

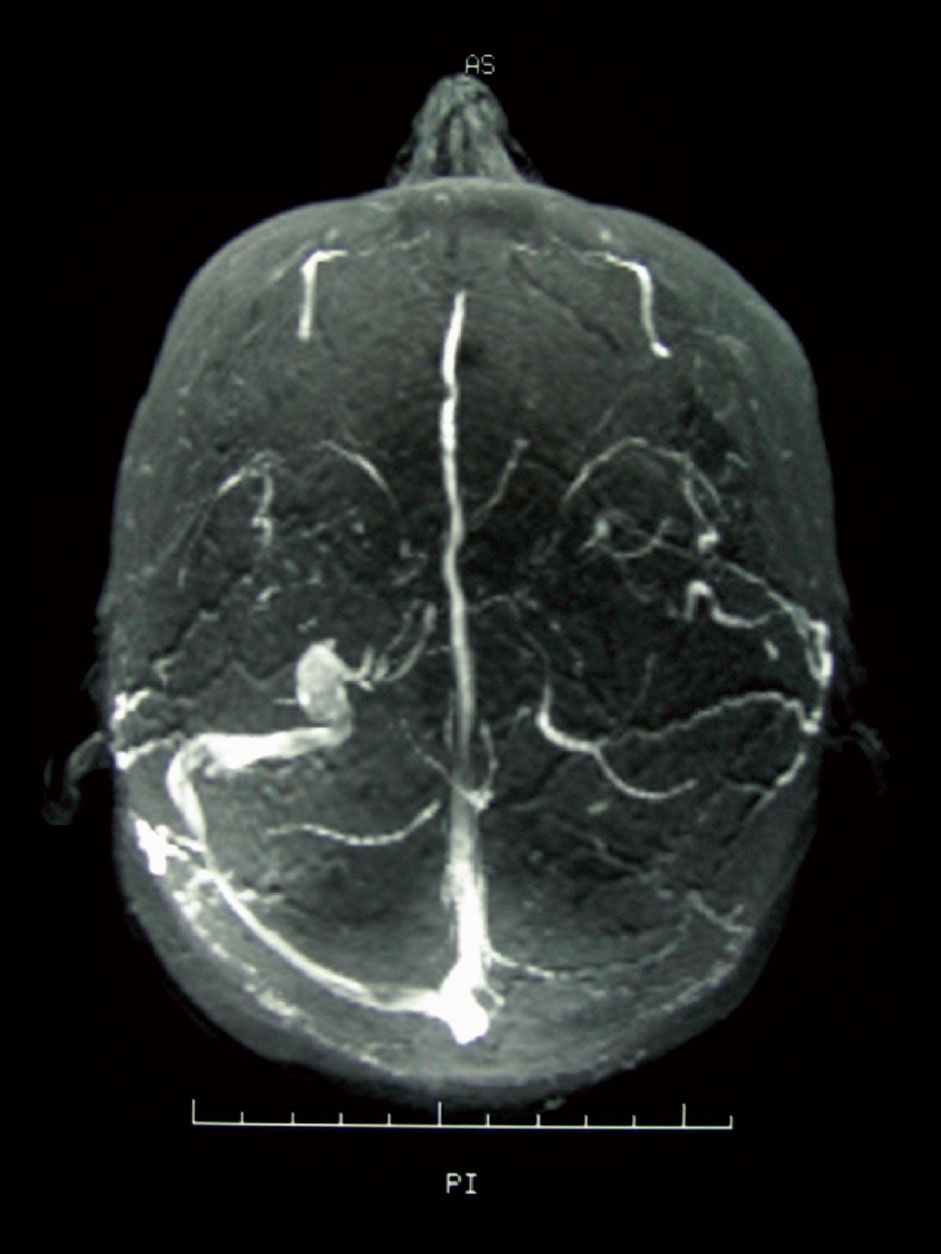

An MRV of a patient demonstrating stenosis of the left transverse sinus. MRV imaging is important in the workup of patients with papilledema, as abnormalities of the dural venous sinus system can affect CSF drainage and ultimately result in increased ICP. Click image to enlarge. |

Occasionally, CT imaging will be urgently needed, as in the case of trauma or the need for CT angiography, and these orders can be processed readily. But what should you do when you need an urgent or emergent MRI and there is a lag time in available MR appointments? This will depend on whether the need is emergent or urgent and, if so, how soon the appointment can be made. Urgent cases that can be scanned within 12 to 24 hours via appointment is usually acceptable. Emergent scans simply cannot be delayed that long. In these cases, the hospital emergency department is often the most prudent way to proceed, but this too requires thorough communication with the attending physicians.

Hospital ED Imaging Referral

As previously discussed, clear communication is key to obtaining neuroimaging. When scans can be scheduled in a timely fashion, communication occurs between you and the interpreting radiologist by way of your orders and the information provided therein. However, when the emergency department (ED) is used for urgent and emergent scanning, you communicate with the emergency room attending physician. Keep in mind that the ED physician is dealing with a whole host of emergencies, whereas we are only dealing with urgent and emergent conditions of the eye and visual system. We know the nuances of the condition in consideration, but the emergency room physician may only have a superficial or rudimentary understanding of these conditions.

Without specific communication as to your concerns and desired imaging techniques, emergency room physicians typically default to using CT imaging because it is more readily available and part of their normal protocol. This is because patients who end up in the emergency room unconscious typically receive CT imaging. The ED physician is concerned about an intracranial bleed; subarachnoid and subdural hemorrhages readily show up on CT imaging.

Take the case, for example, of a symptomatic patient who presents to your office with profound bilateral disc edema and fits the profile for idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). Though this may be your working diagnosis, there are certainly other conditions that can cause this clinical presentation. If you send the patient to the ED with only cursory information, such as something generic like ‘papilledema’, chances are the ED physician is going to order either a CT scan (being concerned about a mass or hemorrhage), or call in a neurologist (causing a time delay) who ultimately will confirm the bilateral disc edema and who may then order either a CT or MR series, significantly delaying the diagnosis. If in fact the patient does have intracranial hypertension, a CT scan will not be useful and further delay proper care. MRI and MRV imaging are standard protocol in imaging patients with suspected IIH, which will be discussed later in part two.

In cases like these, I’d suggest your office call the imaging centers first to determine how urgently the patient can be scanned. If the time frame is not suitable, then you need to call the ED and speak with one of the emergency room physicians, making sure to educate and guide them to your required imaging technique.

The conversation may go something like this: “I am sending a patient to your emergency department for urgent neuroimaging. They presented today with headaches of one week duration and clinical findings consistent with papilledema (education). As you know, papilledema can be caused by a variety of conditions, but our findings are consistent with elevated intracranial pressure, and since the patient fits the profile for idiopathic intracranial hypertension, MRI and MRV are warranted, in lieu of CT imaging (guidance) with emphasis on the intraorbital optic nerve segments, the sella turcica and the transverse dural venous sinuses.”

Conversations of this detail are genuinely appreciated by the ED physician and lead to more efficient neuroimaging. Of course, the conversations will be specific to each individual patient’s problem, but the key is that these thorough conversations offer relevant clinical information and guidance, resulting in a more problem-oriented examination.

Takeaways

| Click here to read Part 2 of this two-part series on laboratory testing and imaging in optometric practice. |

The indications for lab and imaging studies in eye care are numerous, system-wide and can be complex. Nevertheless, they highlight the eye’s intimate relationship with multiple organ systems and physiological processes of the body. The eye may very well set off an evaluation that leads to a diagnosis of abnormality in a separate organ system. Or, the eyes may need to be evaluated because of a known, pre-existing systemic condition with ophthalmic manifestations. With both cases, lab and imaging studies are part and parcel of the management of patients with diseases of the eye and visual system.

Evaluation of these studies is not done in the absence of other healthcare providers; rather, they are done in tandem. Those other providers may be neurosurgeons, rheumatologists, vascular surgeons, internal medicine physicians, neurologists or others. Sometimes it is the other providers who initiate the specialty testing, and other times it is us who initiate the labwork and imaging. Either way, it is imperative that the clinician who sees the patient populations with higher disease rates be aware of the indications, uses and limitations of these studies.

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heildelberg Engineering and Glaukos.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Defining primary care: an interim report. Donaldson M, Yordy K, Vanselow N, ed. Washington (DC):National Academies Press (US);1994. |