|

Ophthalmic clinicians should always be on the lookout for conditions that can quickly result in permanent loss of vision or even blindness. Early detection, diagnosis and appropriate treatment may prevent permanent vision loss or blindness in select cases.

On occasion, the ophthalmic clinician arrives at the correct diagnosis in a case, informs the patient about the urgency of the situation, writes a note (with the presumed diagnosis, tests required and suggested treatment plan) that the patient takes to the ER or ED. Shortly afterwards, the referring doctor speaks via phone with one or more of the ER doctors several times and answers all their questions. But somehow, the ER MD and the hospital consultants might arrive at an incorrect diagnosis. In such cases, it is not unusual for malpractice allegations to be instituted against all the doctors and consultants associated with the hospital and even the clinician who made the initial and correct diagnosis and referral.

Case

A 70-year-old woman presented to her optometrist, where she reported a history of an abscess of two teeth on the right side of her mouth that her dentist treated with antibiotics several days earlier. Coincidentally, she also had a history of temporal mandibular joint (TMJ) problems on the right side of her mouth. The patient believed that the dental issues were responsible for blurred vision in her right eye and jaw pain. She described her vision in her right eye as “filmy.”

Her primary reason for the visit to the optometrist was to update her contact lens prescription and obtain new lenses. VA with a slightly modified prescription was measured at 20/20- OD and 20/20- OS. The external exam included pupillary testing that was normal as well as the absence of afferent pupil defect (APD). The slit lamp exam revealed mild cataracts OU with the right cataract slightly more progressed than the left. IOPs were recorded as 15mm Hg OU.

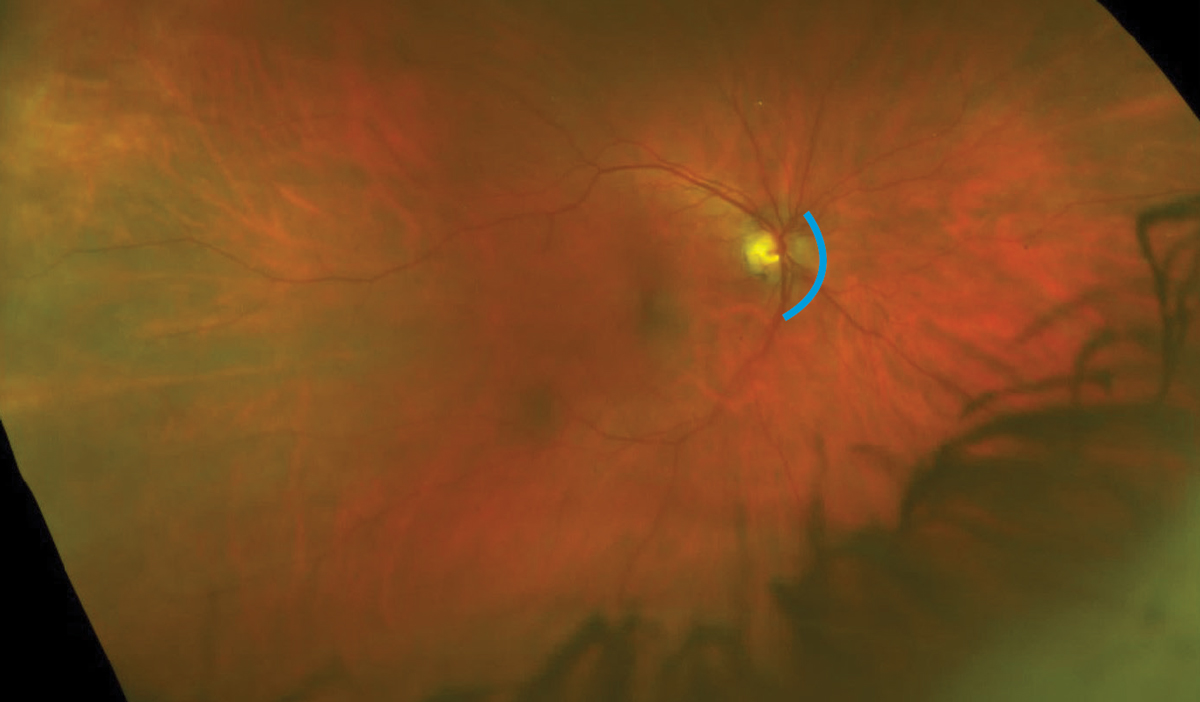

A dilated fundus examination was performed. The cup-to-disc ratio was noted as 0.35 in each eye. Mild vessel crossing changes were observed and attributed to high blood pressure that was being treated. Images of the fundus were also obtained with the Optomap. A zone nasal to the disc in the right eye was believed to be a congenital lesion. New contact lenses were prescribed, and the patient was told to report any changes in her vision.

Two days later, the patient saw her dentist for jaw pain, but the dentist was more concerned about a complaint of worsening vision as well. They called the optometrist, and a second vision exam was performed several hours later within this two-day period.

Now, the VA in the OD was not 20/20- but 20/200. Pupillary testing revealed that the right pupil was now fixed. IOPs were again 15mm Hg OU. Perimetry screening revealed a very abnormal field OD. OCT revealed an elevated optic nerve head in the right eye only. Fundus images with the Optomap now revealed an abnormal optic nerve head with 360º swelling around the disc.

The optometrist concluded that the patient needed immediate treatment, told the patient about the seriousness of the condition and concluded that she must be seen and treated ASAP. The optometrist wrote the following note that the patient immediately took to the ER of a nearby major medical center:

…Sudden loss of vision OD, temple not sore to touch, OD pupil fixed, OD optic nerve head (ONH) swollen (edema) … Please r/o (rule out) giant cell arteritis (GCA) …. Sed rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), consider imaging... please send report…

|

|

Ultra-widefield image OD taken about five years prior to recent episode. The parapapillary disc zone from about one to six o’clock appears blurred. Subtle medullated nerve fibers? Click image to enlarge. |

Making the Wrong Call

Shortly afterwards, the optometrist was on the phone with the ER MDs who asked several questions, such as, “Was a retinal detachment definitively ruled out?” The optometrist said yes and offered to make the fundus images available. The ER MD said that they would take their own photos.

The work-up following the patient’s presentation included ESR and CRP, both of which were borderline high. An ER MD and one of the ophthalmologists who consulted labeled the jaw pain as non-specific. Ophthalmologists and neuro-ophthalmologists were consulted, but in-person evaluations were not performed until the next morning. The diagnosis arrived upon was non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) and steroids were not prescribed, even though the optometrist’s note stated, “Please rule out GCA.”

Several days later, the patient was evaluated at another major hospital after further loss of vision. This exam resulted in IV steroids to be immediately initiated, and then a temporal artery biopsy was performed that proved to be positive. The diagnosis arrived upon was GCA, an inflammatory disorder that often responds to steroids if administered in a timely fashion. When not treated in a timely manner, loss of vision in the fellow eye is quite common. The patient progressed shortly to no light perception OU, and she remains totally blind.

Not surprisingly, the hospital and all the clinicians involved with any aspect of the care were sued.

You Be the Judge

Should everyone be held culpable of malpractice in this case of total blindness?

Did the patient have GCA at the time of the first visit to the OD?

Based upon symptoms and clinical findings, should the OD have made the urgent referral to the ER two days earlier?

If the referring doctor were an ophthalmologist and not an optometrist, would the ER MDs have diagnosed GCA and initiated IV steroids immediately?

Is the standard of care in such a case to begin steroids even before the results of the temporal artery biopsy are available?

If the insurance carrier for the hospital and the MDs settled the case for several million dollars well prior to trial, would the case against the OD then be dropped?

|

|

Ultra-widefield image OD taken two days prior to referral to ER and with a different ultra-widefield device than the previous image. The entire image has far greater clarity and detail than the image taken five years earlier. Note the difference in blood vessels. The disc zone from about two to six o’clock is blurred. Is this just a better image of the same abnormality imaged five years earlier, or is it an early indication of optic neuropathy? Click image to enlarge. |

Comments and Our Opinion

I (JS) was requested to review all the records and about a dozen depositions of all the doctors involved. My conclusion was that the OD met the existing standard of care and even went beyond the minimally acceptable standard of care on the second visit when the OD composed a comprehensive note that should have resulted in a near immediate correct diagnosis and timely IV steroids by the ER MDs. The OD was also available via telephone to answer questions posed by the ER MDs.

Two other OD experts reached a different conclusion and stated in several lengthy written reports that the OD should have diagnosed GCA and immediately refer the patient on the first visit because of the chief complaints and the abnormal fundus as documented with the Optos images.

I responded that the ER MDs and consultants got it wrong even with a detailed note from the optometrist documenting the drop in VA to 20/200 OD from 20/20, and a fixed pupil OD that was normal two days earlier. Would they have arrived at the correct diagnosis two days earlier? Quite unlikely!

We will never know with absolute certainty whether or not GCA was present two days earlier. The jaw pain on the first visit to the OD was believed by the patient and the optometrist to be due to the recent tooth abscess and perhaps also to the long-standing TMJ. (The ER doctors noted two days later that the jaw pain was “not specific.”) The 20/20- VA OD on the first visit and the absence of an APD and a normal disc appearance (as interpreted by the optometrist) certainly did not support a diagnosis of GCA.

The nasal disc zone was interpreted by the optometrist as a congenital lesion, perhaps a form of medullated nerve fibers. Images taken several years earlier were far inferior but also appeared to document a similar abnormal zone. This nasal disc finding years earlier could not be a papillitis due to GCA.

Outcome

The case against the hospital and its many personnel and consultants was quite strong, and the insurance companies involved settled quickly for a total amount of several million dollars rather than risk going to trial. Surprisingly, the case against the OD continued for about another year. The two key defense attorneys and I believed the case could have been won at trial. The representatives of the insurance company for the OD decided to settle rather than risk a culpable verdict and a very large jury award at trial. A jury is generally quite sympathetic to a blind patient. This settlement approached a million dollars.

It is generally agreed that most patients with suspected GCA should be started on oral prednisone 40mg/day to 60mg/day until the results of a temporal artery biopsy become available.1 We feel the frustration for the OD who did the right thing and for the patient who must now adapt to being totally blind for the rest of her life.

| NOTE: This article is one of a series based on actual lawsuits in which the author served as an expert witness or rendered an expert opinion. These cases are factual, but some details have been altered to preserve confidentiality. The article represents the authors’ opinion of acceptable standards of care and do not give legal or medical advice. Laws, standards and the outcome of cases can vary from place to place. Others’ opinions may differ; we welcome yours. |

Dr. Sherman is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry and editor-in-chief of Retina Revealed at www.retinarevealed.com. During his 52 years at SUNY, Dr. Sherman has published about 750 various manuscripts. He has also served as an expert witness in 400 malpractice cases, approximately equally split between plaintiff and defendant. Dr. Sherman has received support for Retina Revealed from Carl Zeiss Meditec, MacuHealth and Konan.

Dr. Bass is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY College of Optometry and is an attending in the Retina Clinic of the University Eye Center. She has served as an expert witness in a significant number of malpractice cases, the majority in support of the defendant. She serves as a consultant for ProQR Therapeutics.

1. Seetharaman M, Albertini JG, Paget SA, et al. Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) treatment & management. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com/article/332483-treatment?form=fpf#d1. Last updated July 7, 2022. Accessed August 21, 2023. |