|

It is well known that the eyes can exhibit signs of systemic diseases and that an eye examination can alert the practitioner to further investigate whether their patient may have a suspected systemic condition. Early detection potentiates the likelihood of early treatment, which can not only save vision but can also save lives. However, there may be times when the best intentions go awry and the ultimate devastating result, which might have been avoided, inevitably occurs.

Case

A college-educated 25-year-old Caucasian female presented with the chief complaint of a foreign body sensation in the right eye. The patient wore soft contact lenses for several years without significant problems. No detailed general health history was obtained on this exam.

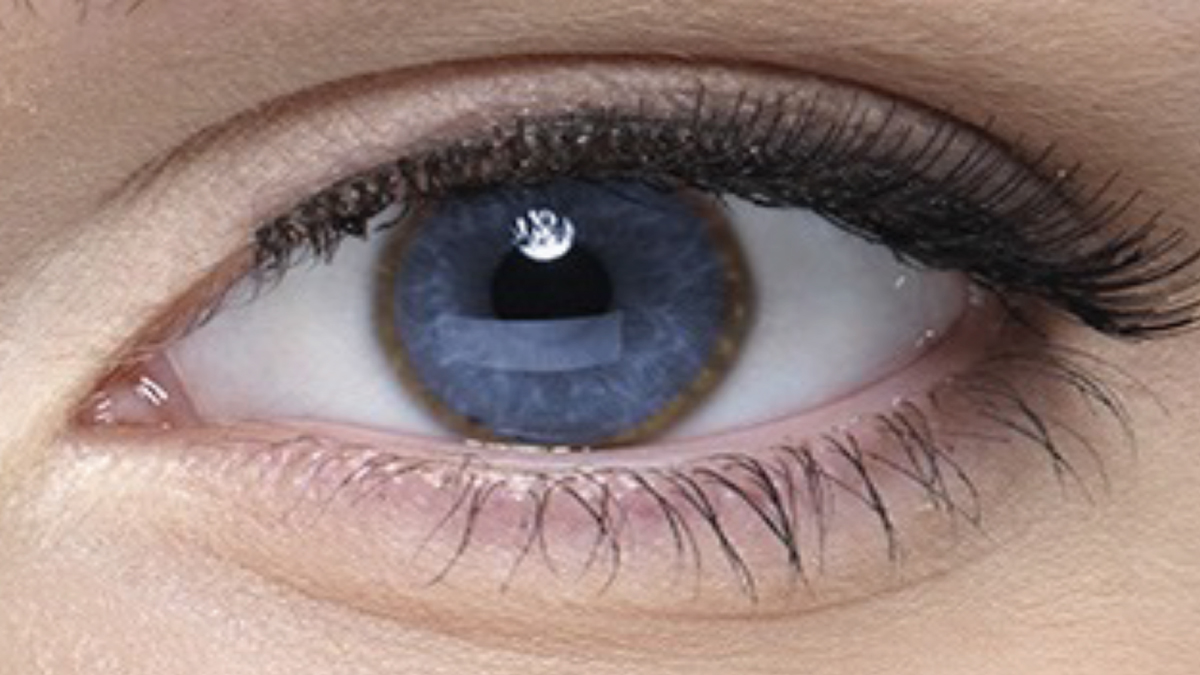

Best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/20 in each eye with contact lenses. A slit lamp evaluation revealed a misdirected lash, which had contact with the inferior conjunctiva. While performing the slit lamp exam, the eye doctor observed a “limbal iridescence” in each eye. Lash removal appeared to alleviate the patient’s symptoms, but the eye doctor requested that the patient return in two days. When she did, she was evaluated by a different eye doctor in the same office. The patient was asymptomatic, and visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. The second eye doctor also performed a slit lamp exam and noted “crocodile shagreen” and suggested a consultation with a cornea specialist. However, it appeared that the patient never bothered to see a specialist.

|

|

Fig. 1. Kayser-Fleischer brownish-yellow ring in the corneal-scleral limbal junction of a patient with Wilson’s disease (not the one described in this case). Photo: Wilson Disease Association. Click image to enlarge. |

Follow-up

Six months later, the patient presented again to the first eye doctor for a routine contact lens check-up. Visual acuity was correctable to better than 20/20 in each eye. A slit lamp exam again revealed a large iridescent ring deep in the cornea near the limbus (Figure 1). At this visit, the eye doctor decided to pursue the unusual slit lamp observation. He consulted The Wills Eye Manual in his office and discovered that the observed rings fit the description of a Kayser-Fleischer ring, which is most often due to abnormal copper deposits in Wilson’s disease (WD), also known as Wilson’s hepatolenticular disease. He then asked the patient about any history of liver problems, and the patient responded that some of her liver enzymes had been noted to be mildly abnormal. She mentioned that her physician believed the liver enzyme disorder was due to the Accutane (isotretinoin, Roche) that the patient was taking for acne, and perhaps due to a prior mononucleosis infection caused by the Epstein-Barr virus.

The eye doctor decided to fax a single-page interprofessional report to the patient’s internist. It listed his observation and the possible association with WD. In his deposition many months later, that doctor testified that he faxed the report and gave the original to the patient, then he told the patient to follow up on it with her internist and he retained a copy for his records. A week later, the patient returned because of a lost contact lens, and the eye doctor asked whether she had seen her internist. The patient had not. On the chart, the eye doctor wrote under the plan section to call the internist.

He never did.

Over the next year, the patient was seen several times by her internist for various problems, including a marked weight gain, but apparently never mentioned the eye doctor’s concern about WD. It appeared that the internist’s staff buried the fax in the patient’s record and never informed the internist that a fax was received. So, the internist was unaware of the eye doctor’s concern. Over this period, the patient began to develop psychiatric symptoms. Two psychiatrists she consulted attributed the problems to her parents’ recent divorce. But as the disorder worsened over many months, one psychiatrist noted increasing tremors and referred the patient to a neurologist to rule out Parkinson’s disease.

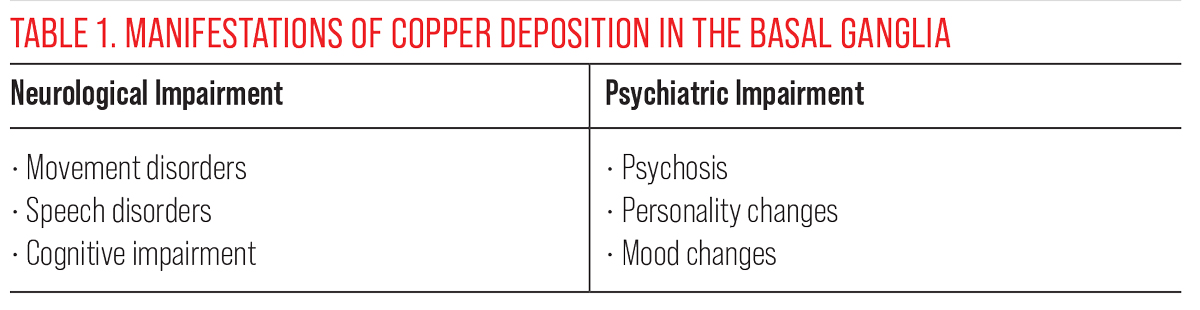

Slurred speech and involuntary hand movements were noted. An MRI revealed copper deposition in the basal ganglia at the base of the brain that resulted in neurological and psychiatric abnormalities (Table 1). Blood and urine testing confirmed the abnormal copper levels, a diagnosis of WD was finally confirmed and treatment initiated. The diagnosis was made about one and a half years after the first eye doctor noted the iridescent corneal rings. Although the patient improved somewhat with treatment, she still suffered from what some doctors have labeled as severe neurological dysfunction.

You Be the Judge

In light of the facts presented here, consider the following questions:

- Did the eye doctor meet the standard of care when he faxed a report to the internist’s office?

- Did the eye doctor meet the standard of care when he informed the patient of his concerns, gave the patient a copy of his report and told her to follow up with the internist?

- The eye doctor said he was going to follow up with a telephone call to the patient’s internist, but never did. Was the eye doctor culpable?

- Did the eye doctor’s responsibility in this case end when he informed the patient of his suspicion, and was it the patient’s responsibility to follow up with her internist?

Malpractice Allegation

Numerous doctors were named in the lawsuit: the two eye doctors from the same practice, three physicians in the patient’s medical group and two psychiatrists were all served. None of the doctors in the medical group who had evaluated the patient over the past five years ever considered a diagnosis of WD.

I (JS) was an expert witness who defended the two optometrists. It struck me when one of the lead attorneys, who was wearing cowboy boots, had his feet on the conference room table. He was far more interested in speed-reading a stack of magazines than in any of the depositions. I chatted with him about why he appeared to have little interest in the contents of the expert testimonies. His response surprised me. To paraphrase: With seven defendants, all with excellent malpractice insurance, there was no reason for the case to go to trial. He predicted that each insurance carrier would prefer to contribute several hundred thousand dollars to the total settlement than risk the uncertainty of a trial.

Outcome: The attorney with the cowboy boots was right. The insurance companies for all the defendants contributed to the final global award, about $2 million for the plaintiff as a result of the delayed diagnosis of WD and about $1 million for the law firm representing the patient.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Not Yet Home

Wilson’s disease is a rare, autosomal recessive genetic disorder that affects the metabolism of copper.1 It is believed to affect between one in 30,000 to one in 100,000 individuals. Signs and symptoms begin early in life, up to age 35. It is primarily characterized by hepatic and neurologic disease. The liver does not excrete copper in the bile, and copper accumulates in several organs, including the eye and brain. Because of copper manifesting in the cornea, eye doctors are in a perfect position to detect this deadly disease early, before the onset of major organ damage.

Neither eye doctor recognized the unusual corneal observation as a Kayser-Fleischer ring at first. This alone does not constitute malpractice because most eye doctors might similarly fail to recognize this rare and subtle observation. The eye doctor who used the term “crocodile shagreen” had the wrong diagnosis but did attempt to refer the patient. The eye doctor who consulted The Wills Eye Manual arrived at the correct diagnosis. He referred the patient back to her internist to confirm his suspicions, but his astute diagnosis and attempt at referral never benefited the patient. In baseball terms, this eye doctor struck out when he first saw the patient but hit a triple months later. However, he never scored a run (in the sense of a benefit to the patient).

But what is the standard of care with regards to referral? Is informing the patient and faxing a report adequate when one uncovers a systemic disease–related finding with significant morbidity and, eventually, mortality if undiagnosed and untreated? Very little is written in the optometric literature concerning the appropriate standard. In his book Legal Aspects of Optometry, John Classe, OD, JD, suggested making the appointment while the patient is in your office and setting up a system to make certain that the appointment is kept.2

What about the patient’s responsibility in this case? The patient was told about the corneal rings and likely connection with WD. She was also given the original referral form and knew that it was faxed to the internist. In her deposition, the patient claimed that she did not think it was a serious problem because the eye doctors who examined her failed to convey a sense of urgency.

As the patient began to gain weight and developed psychiatric and neurological symptoms, she never mentioned the eye doctor’s findings to any of the specialists she was consulting.

This supports the contention that the patient was at least partly to blame for the outcome. Others will argue that, since the condition was already causing psychiatric problems, the patient could not be held culpable in any way.

To avoid malpractice in this case would have meant going beyond the standard. In retrospect, it appeared the OD should have picked up a phone to relay his suspicion of WD directly with the internist. Fax reports (or even scanned or mailed reports) can be easily misplaced in a busy practice, and even if the document was put in the patient’s chart, it could get buried by other documents and never be seen by the treating doctor. This case also points out that relying on the patient to convey important information may not be justified.

Although it is debatable as to whether the OD met the existing standard of care, it is highly recommended in such a case to go beyond the standard and ensure the right information gets into the right hands, especially when suspecting a disease with high morbidity. Decrease the risk of malpractice litigations dramatically by taking the extra step.

With no one on base, ballgames cannot be won with a triple.

| NOTE: This article is one of a series based on actual lawsuits in which the author served as an expert witness or rendered an expert opinion. These cases are factual, but some details have been altered to preserve confidentiality. The article represents the authors’ opinion of acceptable standards of care and do not give legal or medical advice. Laws, standards and the outcome of cases can vary from place to place. Others’ opinions may differ; we welcome yours. |

Dr. Sherman is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry and editor-in-chief of Retina Revealed at www.retinarevealed.com. During his 52 years at SUNY, Dr. Sherman has published about 750 various manuscripts. He has also served as an expert witness in 400 malpractice cases, approximately equally split between plaintiff and defendant. Dr. Sherman has received support for Retina Revealed from Carl Zeiss Meditec, MacuHealth and Konan.

Dr. Bass is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY College of Optometry and is an attending in the Retina Clinic of the University Eye Center. She has served as an expert witness in a significant number of malpractice cases, the majority in support of the defendant. She serves as a consultant for ProQR Therapeutics.

1. Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, et al. Wilson’s disease. Lancet 2007;369(9559):397-408. 2. Classe J. Legal Aspects of Optometry. 1st ed. Butterworth-Heinemann; 1989. |